Marion Engin and Barnaby Priest

Zayed University, Dubai

Peer observation has long been regarded as an integral part of pre-service teacher education programmes and structured certified teacher education courses. However, there is little in the professional literature on successful peer observation experiences with experienced teachers in higher education. This may be due to the logistical problems in organising such a programme, or the fact that the purpose is not always clear (Richards, 1998). The result is that peer observation has gained negative connotations, and teachers who have experienced such contexts may not see the learning value of peer observation. Teachers are more likely to ‘do’ their peer observation to fulfill criteria for appraisal or contract renewal without learning from the experience. A distinction that is not often considered, but lies at the root of the problems in definition and understanding, is that between observing and being observed. When the emphasis is on being observed, it suggests that there is an evaluation of the teacher. However, if the emphasis is on observing, the responsibility lies with the observer to learn from the teaching.

Historically, in the field of teaching English as a second language (TESOL), peer observation was a means for pre-service teachers to learn more about classroom processes and learn from experienced teachers (Gebhard, Gaitan, & Oprandy, 1990). The student teacher was seen as an ‘investigator’ (Gebhard et al., 1990, p. 17), and the observation was a lens through which they could observe others teach. Richards (1998, p. 144) describes how pre-service teachers are involved in “collecting information rather than evaluating performance” which they share with the teacher. An unexpected spin-off was often that the experienced teacher also reflected on their own practice.

With the current changing epistemological perspectives on teacher learning and cognition (Borg, 2003; Johnson, 2009) and recognition of the situated nature of learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), peer observation as a tool for learning (Wajnryb, 1992) is a highly appropriate model for reflective teaching which legitimises practitioner experience and valorises the interactive and social nature of learning. In this paper, we argue that peer observation once again be the process whereby faculty observe peers with the aim of collecting data, analysing the classroom process and reflecting on their own practice. Such an approach to teacher learning puts the onus on the observer as the learner, thus eliminating the evaluation element that has created negative connotations in peer observation programmes (Lomas & Kinchin, 2006). In such an approach to peer observation there is no evaluation of the teacher’s lesson by the observer. In fact, the observer evaluates their own teaching in the light of the observation.

This paper positions peer observation as an enquiry-based approach to learning. For peer observation to be a tool for reflection and learning, there needs to be a context of shared understandings, collaboration, dialogue, mediation, and tools or written artefacts which can structure or guide reflection. This paper will describe how peer observation as a learning tool became an integral part of faculty learning in a higher education context.

One of the problems in discussing and promoting peer observation is that there is no clear definition. Blackwell and McLean (1996, p. 156) state that “Peer Observation of Teaching (POT) is a little used way of stimulating reflection on and improvement of teaching. It is an unusual form of Staff Development (SD) that emphasises continuous processes and peer feedback rather than course attendance”. Peer observation has been categorised into three models: evaluation model, development model and peer review model (Gosling, 2002) as well as having two main purposes: development or performance management (Bell & Mladenovic, 2008). Peel (2005, p. 489) describes peer observation as providing both professional support with colleagues as well as forming part of “quality monitoring processes”. In many cases, the ‘peer’ is in fact a senior manager. Thus, it would seem that peer observation in higher education contexts has both a developmental and evaluative function.

Another aspect is that peer observation often involves a process whereby a colleague is expected to give critical feedback (Schuck, Aubusson, & Buchanan, 2008), but there is little written on how the colleague gives critical feedback and whether there has been any training provided on giving feedback. Feedback is in itself a highly sensitive process (Le & Vasquez, 2011). One result, well documented in Bell and Mladenovic (2008), is that academics may find peer observation intrusive, threatening and highly subjective. This leads to an unwillingness to carry out peer observations, and a reluctance to consider such observations as a learning tool. Bell and Mladenovic (2008) state, for peer observation to work, the conditions need to involve feedback which is non-judgmental and developmental. Despite this call, the checklist provided by the authors to achieve this non-judgmental feedback included statements such as “the tutor effectively managed the tutorial group interaction” and “the aims, objectives and structure of the tutorial were clear”. The terms ‘effective’ and ‘clear’ are highly subjective, and their interpretations can differ from teacher to teacher.

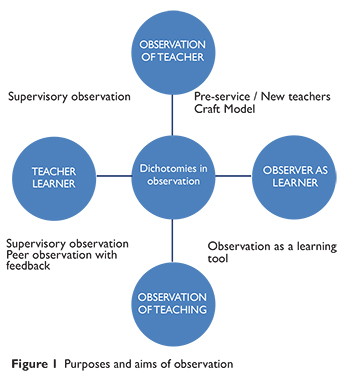

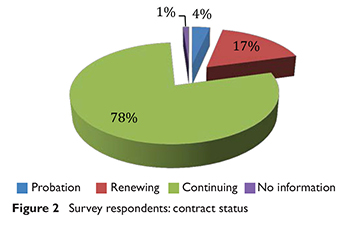

Hendry and Oliver (2012, p. 1) point out that “evidence is increasingly emerging that learning from watching a colleague teach can be just as beneficial as, if not more than, receiving feedback, even when that feedback is well constructed”. Although there has been research into more collaborative approaches to giving feedback to peers (Wang & Seth, 1998), we would argue that peer observation will always be maligned as long as there is a misunderstanding of terms such as ‘peer’ and ‘peer observation’, and a focus on the teacher as the learner rather than the observer. Figure 1 outlines possible purposes and aims of observation in general. It can be seen that peer observation, placed in the bottom right-hand corner, emphasises that the observation focus is the teaching and the aim is for the observer to learn.

Peer observation as a learning tool for the observer puts the onus for learning and reflection on the observer. This creates a non-judgmental, developmental, collegial and reflective peer observation model, mitigating many of the frustrations and challenges mentioned earlier. As Hendry and Oliver (2012) note, a fundamental construct of peer observation as a learning tool is that it encourages, prompts and guides reflective teaching.

It is worth briefly considering the role that reflection plays in peer observations. A major assumption is that “critical reflection can trigger a deeper understanding of teaching” (Richards & Lockhart, 1996, p. ix). By reflecting, the teacher systematically questions, examines and makes decisions about teaching and learning. One aspect of reflective teaching is that it is the teacher that drives the development. The reflective cycle is the “continuing process of reflection on ‘received knowledge’ and ‘experiential knowledge’ in the context of professional action” (Richards & Lockhart, 1996, p. 56). The teacher, through structured activities, becomes aware of their own practice and analyses strengths and areas for development. It is a process whereby experience influences knowledge and the reflective cycle continues (Mann, 2005). The forms of reflection can be many, such as diaries, critical friends, action research and exploratory teaching (Allwright, 2005). The ultimate aim is development, better practice and more effective learning. For reflection to be truly transformatory, it needs to go beyond description and narration and involve analysis and evaluation (Marcos, Sanchez, & Tilleman, 2008). Peer observation can be one tool to stimulate and guide reflective teaching. Observing other teachers is a mirror with which to view your own teaching.

Peer observation has been used in the training of pre-service and new teachers to investigate classroom processes and learn about teaching (Gebhard et al., 1990, p. 21). The student teacher is seen as an “investigator”. This model puts the observing teacher in the place of a learner by observing a more experienced teacher. Wallace (1991), in his model of reflective teaching, describes peer observation as “classroom observation” whereby the observer collects, recalls and analyses data. Again, the onus is on the observer to use the data gathered and reflect on their own teaching. In both contexts, the aim is for the observer to learn from the observation. When teachers, new or experienced, are involved in the activity of teaching, they may not notice certain behaviours of students, the effect of certain activities, or a host of other micro-procedures which make up a lesson. However, peer observation as a learning tool gives observers the opportunity to see classroom processes without the burden of thinking about planning and procedures. Although peer observation in TESOL was initially part of pre-service training, there is growing recognition that mid-service career faculty can benefit from sharing experience and expertise and re-evaluating their practice (Blaisdell & Cox, 2004).

As part of reflective teaching in an enquiry-based approach, the observer can construct personal meaning by observing, analysing data, reflecting this onto their own teaching, and making decisions about further classroom work. Fanselow (1988, p. 115) describes this mirror metaphor in these words: “Here I am with my lens to look at you and your actions. But as I look at you with my lens, I consider you a mirror, I hope to see myself in you and through my teaching”. In other words, observing another teacher stimulates reflection of our own teaching and can be a powerful catalyst for development and change. Since the focus is observing teaching rather than the teacher, there is no judgment making or evaluative feedback. As a result, teachers are more likely to open up their classroom to others, and an atmosphere of learning and collegiality is more likely to be fostered.

In order to encourage the objective process of collecting data to inform one’s own teaching, it is crucial that the observer has a focus or an instrument/tool that can guide the observation and the reflection. Observers may use ready-made tools (see Wajnryb, 1992, for a full list of possible foci) or may make ethnographic notes. It is also important that these notes are used for guided reflection, which follows the stages outlined by Marcos et al. (2008). To this end, a reflection sheet can be used with questions such as “What happened in the lesson, how does this compare with my own lessons and what have I learnt and what am I going to incorporate into my own teaching?” As can be seen, all questions require the observer to take responsibility for reflection and learning.

Thus, a peer observation programme with a focus on observer learning was set up in an English language department of a university in the United Arab Emirates. The aim of the research was to evaluate the extent to which the peer observations did in fact promote learning, to what extent the observers reflected on their teaching and what actual impact in terms of change resulted from the peer observations.

The research aimed to answer the following questions:

Zayed University was established in 1998 on twin campuses in both Abu Dhabi and Dubai to serve the expanding tertiary needs of Emirati students as part of the network of federal tertiary institutions within the United Arab Emirates. The student population in January 2013 surpassed 8,500 students. The department described in this research was the English language foundations programme. There were 147 faculty in the foundations programme in January 2013 across both campuses. The University requires that teaching faculty undertake an annual appraisal process, and in February 2011 it was decided that part of this process should include peer observation.

A system of peer observation was set up in February 2011. It was felt that there would be a positive benefit to be gained from encouraging faculty to observe a colleague and to reflect on their own teaching. In setting up the system, the management team were keen to involve faculty members from an early stage rather than imposing the system in an exclusively top-down manner. A small group of faculty members worked closely with management to research and develop the approach to be taken. It was these faculty members, with support from the management team, who took the lead in developing the strategy, the observation tools and presentation of peer observation to the faculty.

One of the authors, with a colleague, presented the aims and procedures for peer observation in a workshop to all faculty. Care was taken to highlight the role of the observer and to stress that the onus for learning lay on the observer rather than on the teacher being observed. Similarly, the presenters emphasised a non-judgmental, data-gathering, objective approach and shared some possible observation foci and tools to use.

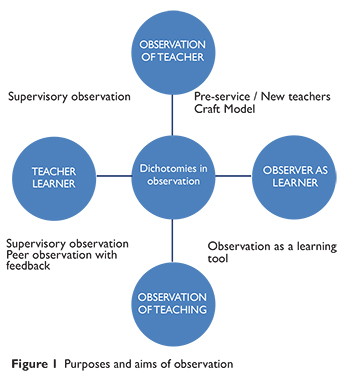

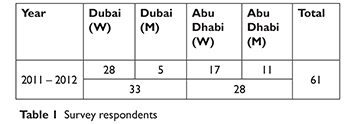

In June 2012, faculty members were sent an online survey consisting of 29 questions about the peer observation process and perceived benefits. Three were demographic questions related to campus and years of teaching at this institution; 18 questions related to the number of lesson observations and pre/post observation meetings; four were related to the focus of the observation and three to the effects and benefits of carrying out peer observations. A list of these questions can be seen in Appendix A. For the purposes of this paper, we examine responses to questions 13–15, 19–21, 27 and 28. Consent was requested from each participant to use the data. The online survey was anonymous. There were 61 responses to the survey, representing a response rate of 41% (Table 1).

A total of 147 faculty members carried out one or more peer observations during the Spring semester of 2012. Faculty were asked to fill in an online survey. The survey was voluntary and anonymous and had 41% response. The contract status of the participants can be seen in Figure 2.

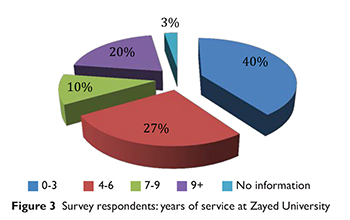

While the majority of the faculty were in mid-contract, there was a wide spread in terms of years of service at the University. Of those surveyed, 40% were in their first contract and a further 27% in their second contract. Overall, 43 of the 87 respondents had more than three years’ experience at the University (Figure 3).

It is interesting to note that many of the teachers who responded to the survey had nine or more years of service with the University, and indeed a significant number (30%) had over seven years of continuous service.

All responses were organised into an Excel sheet according to the question and participant. Thus we could see any correlations across responses; for example, how experience correlated with number of observations, or if there was a pre-observation and a post-observation meeting. Describing and accounting for all correlations are beyond the scope of this paper. However, we discuss some significant correlations in terms of attitude to peer observations. In terms of the qualitative data, all responses were studied several times, highlighting any salient points. There were no a priori codes or categories. The aim was one of discovery, rather than to establish or confirm a priori categories (Richards, 2003). The themes were ‘observer-identified’ (Lofland, 1970, cited by Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995, p. 211) by the authors as the data were examined. Themes became iterative and thus were coded by the authors as categories. The main categories which emerged as common themes for the learning benefits of peer observation were teaching techniques, making comparisons, and affective factors. In terms of critical reflection, the main theme was the re-evaluation of one’s own teaching.

In this section, we present data from the survey according to four main questions. The first area is attitude to peer observation with regard to years of service at the University. The second area is learning benefits from peer observation. The third theme answers the question of how peer observation encouraged critical reflection. The final theme in the data was the impact of observing a peer on teaching.

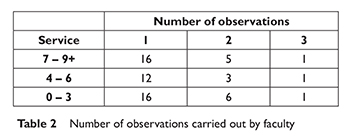

Table 2 summarises the number of years of service in the institution with the number of observations carried out. It can be seen that the attitude to peer observation, as evidenced by the number of observations, is positive across the years of service. Faculty were only expected to carry out one peer observation, whereas in fact some faculty carried out more. It might be anticipated that the longer a faculty member has been in the institution, the less interested they would be in carrying out peer observation, but this was not the case.

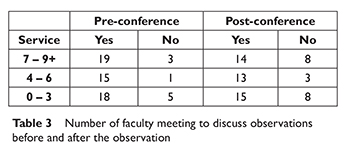

Table 3 describes the number of faculty who met to discuss the observation before and after according to number of years of service. The purpose of the pre-conference was to discuss the class, and to share with the teacher the observation focus. The purpose of the post-conference was to share any notes taken or any data recorded with the class teacher, and for the observer to reflect on the lesson with regard to his/her own teaching. The purpose was not to give the teacher feedback. It is important to note that a pre- and post-conference were also voluntary.

Again, it can be seen that more years of service did not correlate to fewer teachers participating in meetings before and after the observation. Interestingly, the middle group of faculty who were in their second contract period were less likely to have a pre- and post-conference.

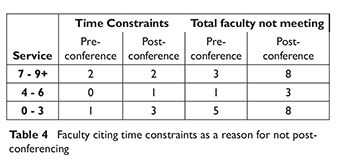

Working in a busy teaching environment, it might have been expected that more teachers would have cited time constraints as a reason for not meeting for a post-conference. However, the figures indicate that this was not the case (Table 4).

Faculty comments focused on lack of need to meet up as the focus was on the observer rather than the teacher being observed. One participant made the following point: “Didn’t really have time or feel it was necessary. I was watching for my own benefit so I didn’t think I really needed to share my observations with the teacher”. It is clear that the observer is focused on the observation as an opportunity to learn and reflect on his/her own teaching. Thus, it was felt a post-conference was not necessary. One observer commented extensively on this point:

We did speak briefly during the lesson, but as the observation is supposed to be about the observer’s development as I understand it, a meeting seems unnecessary. When you ask a teacher if you can observe them, it seems that’s already an imposition. I also think that a post observation meeting might create the impression that I am observing in order to provide feedback – I don’t think that’s a comfortable role for peers. I do not represent ZU management/policy makers etc. Who’s to say my opinions are of any relevance to improving the teacher’s teaching. What I get from observing another teacher is the chance to compare how I do things with how someone else does them and the classroom effects of those decisions i.e. personal reflection.

From this quote we can see that the faculty member has fully embraced the notion of observing for learning. The observer is also very conscious of the atmosphere in which the observations are taking place. As mentioned earlier, often peer observation is maligned due to programmes where teachers receive feedback from peers. The feedback may often be highly critical, given by a teacher who has had no training in how to give feedback. The result is a negative attitude to peer observations. The faculty member refers to this sensitive issue of critical feedback.

With one notable exception, comments from respondents with over seven years of service were overwhelmingly positive, particularly as to the value of the observation. One participant noted: “[I learnt] a good deal, as I taught more or less the same type of lesson with a higher level prior to the observation, and the motivators in the observee’s classroom helped shed light on my students’ lack of motivation and content knowledge”.

Thus, longer years of service did not correlate with less positive attitudes. This supports the findings of Blaisdell and Cox (2004), who state that mid-career faculty need and appreciate the opportunity to re-evaluate their teaching through professional development activities.

This section will present and discuss two themes which emerged from the question “What have you learnt from observing a peer?” This question has been chosen as it represents a window into discovering what teachers felt they gained from observing rather than being observed. The emphasis of this paper is that peer observation is a learning tool for the observer, and thus this section focuses on how much this was seen in our data.

Teaching techniques, such as error correction or question types, are considered low-inference categories in observation. These are techniques which are “readily recognizable and specific” (Day, 1990, p. 48). The observer can identify and describe particular low-inference categories and comment on them. Low inference categories are commonly used in teacher observations as checklists, thus it could be argued that description of and reflection on specific teaching techniques is easier than description of atmosphere, motivation and other less tangible aspects of teaching and learning.

The ease with which techniques can be listed, categorised or described is clear in this comment:

I learnt the following. 1. How to start using the internet as a teaching tool in the classroom. 2. How to pair students using a randomized computer generated grouping software. 3. How to use word magnets as a teaching tool. 4. How to efficiently manage students while using computers and avoid losing their attention.

This list is very comprehensive and many things were gained from one lesson. Clearly, the lesson featured a number of technological aspects and the observer could see the differences in their own teaching. Having observed such specific techniques, the observer can try these in their own classroom.

Teaching techniques may also include classroom management, materials selection and materials use in class. Although classroom management involves many different aspects of teaching, observers may notice different techniques for managing the class. The following comment displayed such thinking: “A different way to use some materials for presentations, some ways of organizing students, and a great idea for st–st evaluations”.

This observer has again listed specific teaching techniques, and it is clear from the last comment that they will probably try out a new idea of student–student evaluations. Observing a different technique in a colleague’s class has prompted them to compare their observations to their own teaching and encouraged them to try something new.

Some responses were a little vague and almost generic. One possible reason for this could be that the observer came away from the class with a general impression rather than a specific technique. Another possibility is that the teachers were filling in the questionnaire as quickly as possible. Generic responses included comments such as “ideas about making the class more lively” and “I picked up some new approaches to classroom management and new activities to try out in class”. It is very possible that the observer came away with such a memory of the class, but the lack of preciseness in the description of what new activity to try out, or what the new approach is, suggests that the observer may not try out anything new in their own class.

There is little discussion on the benefits of peer observation in terms of affective factors (Murdoch, 2000). Such factors can include confidence, reassurance and motivation. Peer observation is not only a cognitive activity; it is also an exercise which can promote collegiality and a learning environment and atmosphere as well as bring affective benefits to the observer and the teacher. In many departments, there is often an attitude that teaching is a secretive activity which takes place behind closed doors; the prevailing discourse is often one of wonder and curiosity about others’ teaching. Peer observation provides an opportunity to open up the doors and reveal what is taking place on an everyday basis. Regardless of what teachers observe, this is in itself a reassuring activity. Some participants commented on the opportunity to go into colleagues’ classes: “Observation allows me to see what other teachers are doing in the classroom. I often come out with ideas for things that I might use in the classroom”. “Always nice to see how someone else manages a classroom. Nice to see other people teach”. One participant particularly referred to how teaching is often an activity done in isolation from others: “It’s nice to share, it’s good to know where you fit in as we work alone all the time, it’s useful to be able to learn things from others”. Eddy and Garza Mitchell (2012) specifically refer to the importance of faculty sharing to diminish the notion that teaching is a solo activity and to motivate experienced faculty to be more engaged in the learning process.

The following comments revealed the importance of peer observation as a tool for encouraging collegiality: “Getting to know a colleague on a different level”; and “I also found that my peers were more than happy to share materials, sites and resources that they found useful”.

Opening up the classroom through peer observation also gave confidence to some teachers. This confidence stemmed from confirmation that what they were doing was acceptable. The following comments reveal these benefits from peer observation: “I confirmed the idea that it is okay to be by myself”, “reassurance of my own teaching practices” and “confidence – based on the management styles and approaches to teaching that I observed, I feel that I am on track with regard to our student population”.

Reflection on teaching needs to go beyond description and should involve analysis and evaluation (Marcos et al., 2008). The analysis is systematic and prompted by a task or an activity. Observing a peer can create the opportunity to systematically compare one’s own teaching with that of another. This is similar to the theme of comparisons described above, although reflection perhaps goes one step further through analysis and evaluation.

The following comments reveal the power of self-evaluation: “I find peer observations a very useful tool. It is easy to fall into routines, and seeing colleagues can lead to a re-evaluation” and “makes you evaluate how you do it and it helps you think of new things to do”.

As mentioned earlier, an aim of reflection is that experience influences knowledge so the learning continues. Part of this experience is the discussion of the observer’s learning points. One observer commented on this strength: “I think it’s an excellent tool as it gives you a mirror by which you can reflect on the way you teach your own class. In the post-lesson meeting it also gives you a chance to discuss issues you may have with your colleague, and get some advice or suggestions from them.”

There may be surprises when experience is gained from observation. One observer commented, “it is always useful and interesting to watch someone else teach. Often what you go in thinking that you might learn is different to what you actually take away from the experience”.

Despite the mostly positive response to peer observation as a tool for reflection, there were some teachers who did not feel that the observation prompted critical reflection. Some felt that they already reflected on their teaching: “I already do a fair amount of reflection, so it wasn’t especially useful”. Nevertheless, peer observation was overwhelmingly seen as positive for self-reflection. The activity of seeing something different that can act as a mirror to your own teaching is seen as an effective way to evaluate yourself and learn.

One of the fundamental reasons that teachers engage in professional development is to improve the learning experiences of their students (Brancato, 2003). In fact, the movement of the scholarship of teaching and learning is based on the construct that a focus on effective teaching contributes to more effective student learning. In fact, some would argue that peer review is not the most important factor in evaluating teaching: “The validity of the quality of teaching is more about the extent to which scholarship has made any difference to teachers’ instruction and student learning and less whether or not it is reviewed by colleagues” (Kreber, 2005, as cited in Laksov, McGrath, & Silen, 2010, p.5).

There are several ways of considering impact and change. There is immediate change in that the observer may go to their next class and use a technique from the observation. However, there is also the more subtle process of change, which involves reflection, analysis and planning. The following responses were to the question “To what extent will you change your teaching practice as a result of undertaking a peer observation, or being observed yourself?”

Responses varied from very general comments such as “a little tighter in my classroom management of students” and “try new ideas, strategies that I liked during the observation” to “anytime I observe something new that works with the students, I try to incorporate or change my teaching practice to include it”. These comments suggested the former type of change, in that teachers could immediately take an idea and incorporate it into their own teaching.

Some responses recognised that there would be small ‘tweaking’ but nothing major: “I will use some new technology and try a few new methods. No fundamental changes”, “not radically but more refining my techniques”, “adaptation of new techniques”. These comments point to adaption rather than adoption. The observer notices new techniques but will make changes to suit their own style of teaching. This process suggests critical thinking and deep reflection by changing what has become familiar and creating a mental “disturbance” (Vygotsky, 1986).

Some participants noted that there would be no changes at all as a result of peer observation: “Not much”, “it will make very little difference to my own teaching”, “I won’t”, “none, I am an excellent teacher but can always use and learn different techniques and ideas”. This last response suggests that the writer sees change only as a fundamental shifting of teaching philosophy, whereas in fact change can be at the levels described above, which is adoption and adaption.

The meaning of ‘change’ provoked a few interesting responses which reflected a deeper thinking on the topic and analysis more akin to scholarly teaching: “Tweak and adjust, rather than change”, “I don’t know if change is the right word but it definitely does inform my teaching. You keep those experiences with you to draw on in similar circumstances”.

Finally, some participants viewed change as a more long-term process of reflection, evaluation and adaptation. “I would, and do, constantly reflect back mentally on the experience of the observations while I’m teaching and I’d say it has improved my teaching quite considerably”. The suggestion here is that peer observation is not a one-off activity, and the changes do not take place immediately as a result of that observation. Development is a long-term process of observing, reflecting and learning and should be a significant part of a professional’s life to keep up with the constant changes in education (Roscoe, 2002).

Several issues emerge from the literature, which are particularly relevant to this study. Firstly, writers who support peer observation as a tool for learning were mostly referring to pre-service or novice teachers (Gebhard et al., 1990). However, we argue that in this context peer observation was an effective tool for learning for experienced teachers. Eddy and Garza Mitchell (2012) discuss how professional development activities such as sharing and reflection can “reinvigorate” experienced faculty. We would strongly agree that this was the case in the context presented.

A second issue is the emphasis on observing and being observed. From the literature on peer observation in higher education it seems as though the latter is the focus (Bell & Mladenovic, 2008; Peel, 2005). Thus, being observed equates to being evaluated. The evaluation may be from a colleague (Schuck et al., 2008), but it is still evaluation. The position of the authors is that an emphasis on observing removes this element of evaluation and judgment-making by putting the onus of learning and reflection on the observer. In this case, the observation becomes a more active and dynamic process, with the lesson acting as a mirror for the observer to analyse their own teaching. We would suggest that the process of observing a peer as a learning tool be renamed ‘observing teaching’. This would eradicate any connotations of evaluation and underline the emphasis on teaching and not the teacher.

From the data, it was clear that teaching involves both cognitive and affective aspects. Observing a peer teaching may result in some ideas or techniques for teaching, or, at a deeper level of reflection, it may encourage comparisons and self-evaluations of teaching. Similarly, observing a colleague teaching may give motivation and confidence to a peer. The data point to the rich reflection and learning opportunities possible in peer observation, both in terms of low inference categories and high inference categories of teaching. If peer observation is introduced as a tool for collecting data on which to reflect on teaching, in an atmosphere where the onus is on the observer to learn, rather than the teacher, then there may be much to learn and reflect on.

Peer observation also disproves the notion that teaching is a “sole activity” (Eddy & Garza Mitchell, 2012). This is important in an environment where collegiality is being nurtured. It may also result in confidence building through reassurance that what happens in one classroom also happens in other classrooms. The observation may result in further collegial activities such as sharing materials or discussing teaching outside the peer observation. Observing a peer may result in a multi-layered outcome of benefits to teachers, the department and the climate of trust and collegiality. As Cosh (1999) points out, reflection and learning take place not when others observe and evaluate us based on their assumptions, but when teachers observe others and question their own assumptions about teaching. There will be an impact on teaching and learning, but this may take time. As one participant wrote: “I think the changes are probably small, but cumulative. Overall, it helps me to be a more mindful teacher”.

Marion Engin has been teaching for 25 years and training for 20 years. She has worked in primary, secondary and tertiary levels. She is currently teaching in the Department of Languages, University College, Zayed University in Dubai.

Barnaby Priest has been a K-12 and tertiary EFL professional since the early 1980s. He has extensive experience as a teacher, teacher trainer and EFL/ESL manager in Europe, SE Asia and the Middle East.