Loc Doan

Global Policy Institute, London, UK

The significance of feedback to student learning has been increasingly underlined by higher education (HE) authorities and institutions. For instance, in section 6 of Assessment of students in the Code of practice for the assurance of academic quality and standards in higher education, the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) in the United Kingdom explicitly underscores the importance of feedback (QAA, 2006, p. 20). Again, in its Understanding assessment: its role in safeguarding academic standards and quality in higher education, the QAA regards it as an essential part of promoting student learning (QAA 2011, p. 12). In its Policy on Giving Effective Feedback on Assessed Work, Aston University (2009-10) states that it emphasises the activities that encourage students to reflect on and review their academic work to improve their performance. It is also commonly accepted in the literature on HE that feedback is a fundamental component in the learning cycle, providing for reflection and development (Weaver, 2006, p. 379). For example, Dowden, Pittaway, Yost, and McCarthy (2011, p. 1) see it as intrinsic to the business of teaching, and Hattie and Timperley (2007, p. 81) emphasise that it powerfully influences learning. In the same way, Orrell (2006, p. 441) argues that it is the cornerstone of all learning. Other researchers and practitioners in HE who hold that feedback has a crucial role to play in underpinning student learning include Hattie, Biggs, and Purdie (1996), Hattie and Jaeger (1998), Hounsell (2003), Mutch (2003), Smith and Gorard (2005), Race (2007), Lizzio and Wilson (2008), Irons (2008), and Shute (2008).

Yet, the relevance of feedback to student development is not universally agreed because while feedback is regarded as indispensable to the process of learning, there exists a widespread belief that many students are disengaged from the feedback process (Price, Handley, & Millar, 2011, p. 879). Indeed, some scholars, e.g. Ding (1998), Ecclestone (1998), Wojtas (1998), and Fritz, Morris, Bjork, Gelman, and Wickens (2000), do not consider feedback to be a main aspect of learning because for them students do not really value it (Higgins, Hartley, & Skelton, 2001, pp. 270-271). For instance, Wojtas (1998) maintains that some students threw away the feedback if they disliked the grade, while others did not collect their marked work. According to Weaver (2006, p. 379), academics complain that feedback does not work because students are more interested in their grade and pay little attention to it. Similarly, Carless (2007, p. 47) points out that some tutors believe that no matter how carefully composed their feedback, students give to it only cursory attention. Gibbs and Simpson (2004-2005, p. 20) also note it is not inevitable that students will pay attention to feedback even when it is lovingly crafted and provided promptly. In the same way, Crisp (2007, p. 572) reminds us that it is not uncommon to hear academics complaining that, despite the many hours they spend providing feedback to students, it often feels like wasted time. The comments about students’ indifference to their tutors’ feedback and the ineffectiveness of feedback to student learning are intriguing because they show there are still differing views among scholars and practitioners in higher education over student engagement with feedback and its role in student learning.

Another issue that is related to the view that feedback does not work is the argument that there exists a lack of understanding between tutors’ intentions when they provide feedback and students’ perceptions when they receive feedback (Lea & Street, 1998; Orrell, 2006; Adcroft 2011; Orsmond & Merry, 2011; Robinson, Pope, & Holyoak, 2013). The key concern raised by those who argue that there exists such a gap is whether students are able to use tutor feedback (Chanock, 2000; Higgins, 2000; Higgins, Hartley, & Skelton, 2002; Orsmond, Merry, & Reiling, 2005) or see connections with how they can improve their work in the future (Cartney, 2010, p. 551). For instance, Higgins (2000, p. 1) maintains that many students are unable to understand feedback comments and interpret them correctly. In other words, there are question marks over students’ ability to implement – and consequently, their confidence in using – tutor feedback to improve their learning.

The aim of this study is to clarify these two issues, namely whether students are uninterested in tutor feedback and whether they are unable to use it as some researchers and practitioners in HE assume. More precisely, drawing on empirical data acquired from a questionnaire survey on students at Aston University, it attempts to address the following questions:

Thus, it is clear that this study does not examine tutors’ perspectives of feedback, or more exactly, their perceptions of students’ responses to their feedback. Rather, it focuses on students’ views of tutor feedback. In other words, it seeks to offer a student perspective on tutor feedback. By investigating these issues, this inquiry-based piece of research is intended to contribute to the current literature on the topic of feedback to students and particularly on perceptions of tutor feedback. According to Carless (2006, p. 219) and Weaver (2006, p. 379), tutor feedback remains a relatively under-researched subject. Weaver (2006, p. 379) also points out that there has been little empirical research published which focuses on student perceptions of tutor feedback. Similarly, Poulos and Mahony (2008, p. 144) underline that research on students’ perceptions of feedback remains thin. Furthermore, with exceptions such as Weaver (2006), little has been ventured to examine what affects students’ ability and confidence in using tutor feedback. Therefore, the study also aims to fill this gap in the literature on tutor feedback.

To make clear what feedback means in this study, it is worth explaining the term. Such a clarification is vital given the fact that although it is “a commonly-used word, feedback does not have sufficient clarity of meaning either in pedagogic literature or practice” (Price, Handley & Millar, 2011, p. 880; Burke & Pieterick, 2010, pp. 3-4). In fact, there are three major points that should be clarified.

First, generally speaking, feedback is defined as information provided by an agent (e.g. tutor, parent, or friend) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p. 81). As noted, this study mainly focuses on tutor annotations and comments on student learning in general and on specific aspects of their learning, e.g. essays. However, to understand better students’ perceptions and reactions vis-à-vis their tutors’ feedback, it also briefly looks at their attitudes towards feedback in general, i.e. their responses towards feedback given by their friends. Furthermore, this study encompasses all forms of feedback, e.g. written, oral and online, that tutors give to students on all aspects of their learning, including on drafts or on finalised assignments, prior to or after submission. This means it does not focus on a particular form of feedback but all types of feedback.

Second, tutor feedback is not (or should not be) seen as a one-way communication, i.e. tutor response to student learning. Rather, it is (or should be seen as) a two-way process, in which tutors give information to students about their learning and students, in turn, use tutors’ comments to redirect or improve their learning (Dowden, Pittaway, Yost, & McCarthy, 2011). In this sense, feedback is not a product but rather a long-term dialogic process, in which both tutors and students are engaged (Bailey & Garner, 2010, p. 188; Price, Handley, & Millar, 2011, p. 879). Feedback as a dialogue and the importance of dialogue in the feedback process is also underlined by Crisp (2007), Nicol (2010), and Orsmond, Maw, Park, Gomez, and Crook (2013). That is why Price, Handley, and Millar (2011, p. 879) classify it into two forms. One is external feedback, i.e. given by tutors making a judgement on students’ work, and the other is internal feedback, i.e. generated by students as they reflect on their work in relation to a performance goal. As already underlined, this study mainly looks at student responses, i.e. internal feedback, to tutor feedback or external feedback, by exploring whether students use their tutor feedback to enhance their learning. However, as will be illustrated later in the section on this study’s findings, the quality of tutor feedback significantly influences student reactions to it.

Third, in terms of its roles, tutor feedback serves multiple purposes, ranging from diagnosing problems, correcting errors, justifying a grade, to giving guidance for future development (Carless, 2006, p. 220; Price, Handley, & Millar, 2011, p. 880). Price, Handley, Millar, and O’Donovan (2010, p. 278) classify the roles of feedback into five categories, namely correction, reinforcement, forensic diagnosis, benchmarking and longitudinal development, with the first four being more concerned with work already done whereas the latter focuses on future development. In this sense, the roles of feedback can be regrouped into two broader categories. The first, which is closely related to summative feedback, primarily deals with the work that has been already carried out (Price, Handley, & Millar, 2011, p. 880). In contrast, the second function, which has been increasingly emphasised in the literature on feedback, explicitly addresses future activity, i.e. giving advice for future improvement (Carless, 2006, p. 220; Price, Handley, Millar, & O’Donovan, 2010, p. 279). As it is used to improve students’ future development, this form of feedback is referred to as formative feedback, i.e. information communicated to learners that is intended to modify their thinking or behaviour for the purpose of improving learning (Shute, 2008, p. 153). According to Orsmond, Merry, and Reiling (2005, p. 369), students use formative feedback in six ways, namely (a) to enhance motivation, (b) to enhance learning, (c) to encourage reflection, (d) to clarify understanding, (e) to enrich their learning environment, and (f) to engage in mechanistic enquiries into their study. Given its focus on future learning, the formative feedback is also known as feedforward (Duncan, 2007, p. 271; Race, 2007, p. 74; Irons, 2008, p. 9, Price, Handley, Millar, & O’Donovan, 2010, p. 278). This study assumes that these two functions of tutor feedback are relevant to students.

The aim of the study is to examine student perceptions and reactions in relation to tutor feedback, and this research suggests that those who are in the best position to give views on these issues are students themselves. For this reason, the research, which was approved by the departmental ethics board, used questionnaires to collect information from students. Like other research methods, be they qualitative or quantitative, questionnaires have their own disadvantages. Yet, they are more suitable for this research because they offer a number of advantages that other research techniques, such as interviews, cannot (Cargan, 2007, pp. 116-117; Denscombe, 2007, pp. 169-170). One of these is that they provide large amounts of information which is accurate, standardised and pre-coded and, consequently, can produce results that are far more valid than qualitative research methods, e.g. interviews. Another is that respondents have greater feeling of anonymity and thus are more comfortable in expressing their real feelings on relatively personal topics, e.g. tutor feedback.

In terms of questionnaire distribution, they were randomly handed out to students who studied individually or in groups in Aston University’s main library and were collected after about 15 minutes. The rationale for choosing this distribution and collection method was threefold. First, it helped improve the return rate. In fact, 200 questionnaires were handed out during the two visits to the library on 27 March and on 4 April 2013, and 188 students completed and returned them (i.e. a 91% response rate). This return rate was higher than that of the survey conducted by Higgins, Hartley and Skelton (2002, p. 55), who distributed the questionnaires before the end of their lecture and got a return rate of 77%. It was also much higher than the response to the survey of Weaver (2006, p. 382), who surveyed 510 students but only 44 of them replied (i.e. a return rate of 8%). Second, instead of focusing on a particular cohort of students, for instance the students’ school or their programme of study, the study aimed to target a wide range of participants so that it could have a neutral and general view of their perceptions of tutor feedback. Finally, randomly asking students to complete the questionnaires offered very rich and relevant information and data, which we could compare and draw some key conclusions because those who completed the questionnaires and returned them were very diverse in terms of their year of study, programme of study, school, gender and age. For instance, as will be shown later, the study discovered that fourth-year students were relatively more confident in using feedback than their first-year peers.

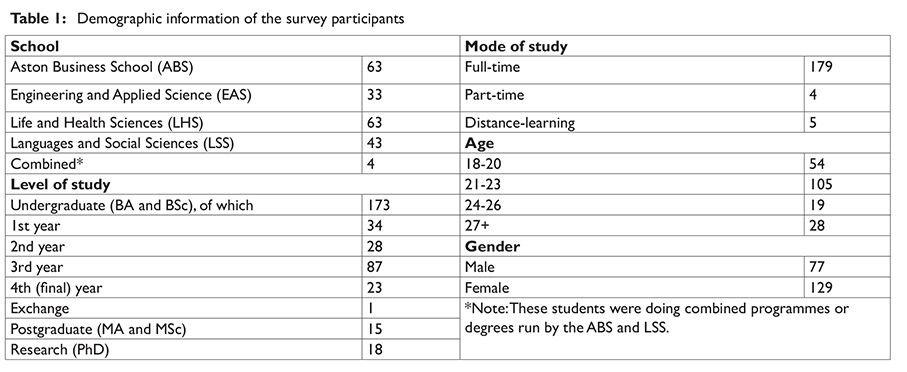

As there were not any research students among these 188 respondents and with the aim to reach a balanced view, the author decided to email the questionnaire to about 60 research students of the School of Languages and Social Sciences (LSS). Eighteen of them (i.e. a 30% response rate) returned their completed questionnaires. With these 18 responses from the LSS research students, the total of the students surveyed were 206 (see Table 1).

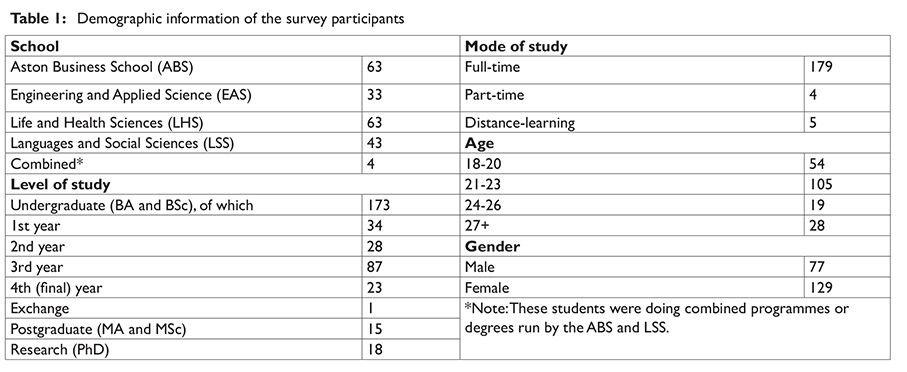

Regarding its structure, the questionnaire was designed to ask students to give their views on a number of issues regarding tutor feedback that the study aims to address. The core of the questionnaire was the questions that asked respondents to give their opinions – from strongly disagree and disagree to agree and strongly agree – on a set of statements regarding feedback. The statements were the comments and arguments made by researchers and tutors that were extracted from the scholarly literature on feedback surveyed by the author (see Table 2). These statements were chosen because they are typical and critical views of feedback. There was also an open question, which asked students to name three factors that make them value tutor feedback, and three ones that make them devalue it. Overall, the huge and relevant amount of quantifiable data that this questionnaire survey generated enabled the study to reach the following findings.

When asked to give their views on a comment that students are more interested in their grade and pay little attention to feedback, of 206 respondents, 17 indicated strongly disagree, 57 disagree, 78 agree, and 54 strongly agree. If the responses are based on a 1-4 point scale with the responses of 1 and 2 representing disagree and those of 3 and 4 standing for agree, only 36% (74) of the 206 students surveyed disagreed with that statement while 64% (132) agreed with it. They were also asked to give their opinions on another comment that students give to tutor feedback only cursory attention; 24 said strongly disagree, 84 disagree, 84 agree, and 14 strongly agree. This also means 52% (108) disagreed with that statement and 48% (98) agreed with it. Premised on the views given by the 206 students surveyed, it is apt to say that, for students, quantitative marks are more important than qualitative comments (Duncan 2007, p. 272). In this sense, some experts, e.g. Ding (1998), Ecclestone (1998), Wojtas (1998), may be right to hold that students are more interested in their grade, i.e. numerical/quantitative mark, than in tutor feedback, i.e. qualitative comments. Yet, the view that students pay only cursory attention to tutor feedback is not completely convincing because more than 50% of the survey participants disagreed with it. More significantly, the number of respondents saying that only the numerical grade is of interest to students and that students hardly pay attention to tutor feedback was high because the respondents were requested to give their views on students’ attitudes to tutor feedback in general, not on their own experience in relation to it. Indeed, when asked to share their own views on their own attitudes towards tutor feedback, the participants expressed that they strongly valued it.

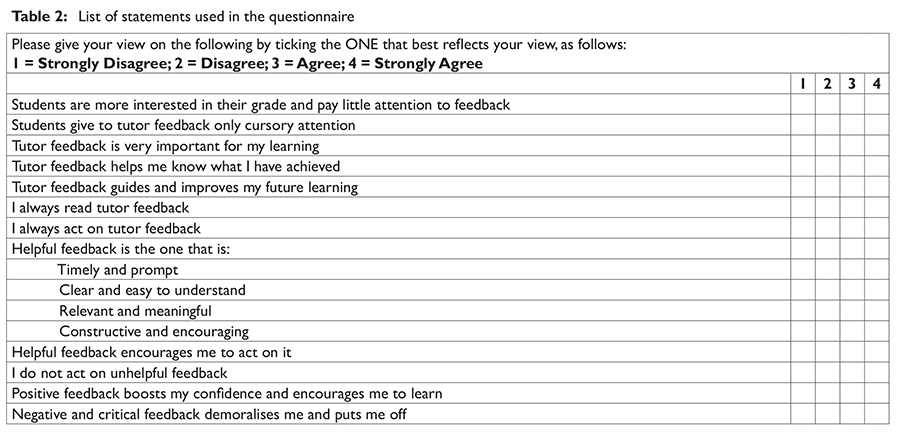

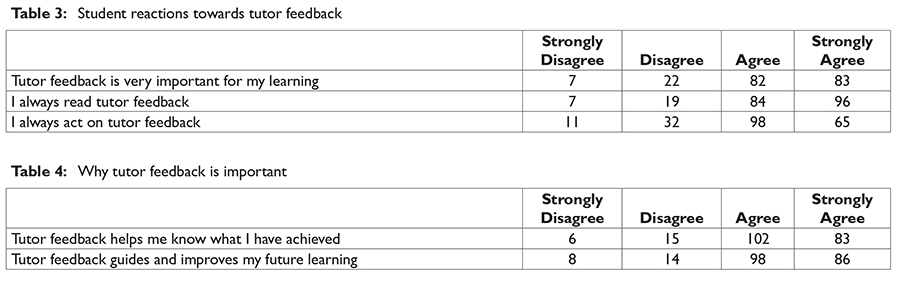

More precisely, as shown in Table 3, of the 206 respondents, over 80% (165 agree and strongly agree) regarded tutor feedback as very important to their learning, 87% (170) always read it and 79% (163) always acted on it. Judging by these responses, a point being made at this stage and which will be discussed in more detail in the last section is that students do not ignore tutor feedback as Ding (1998), Ecclestone (1998), Wojtas (1998), and others suggest. Instead, most of them are receptive to it and act upon it. In other words, the perception of students being only interested in their grades was not supported by the findings of this survey. Another related point drawn from this finding is that those who argue that students are indifferent to tutor feedback probably base such an argument on their own perceptions rather than on empirical facts.

The question raised is why students regard tutor feedback as significant to their learning. It has been noted earlier that two broad functions of feedback are to give students information on their already done work, e.g. their strengths and weaknesses, and to offer advice and guidance for their future development, e.g. the area or the way to improve. As illustrated in Table 4, tutor feedback is of importance to students because it helps them know their past achievements and enhances their future development. Ninety per cent (185 of 206) of respondents said that tutor feedback helped them know what they have achieved and 89% (184) indicated that it guided and improved their future learning. In other words, they find feedback useful in two particular ways, namely learning what they have achieved and knowing what or how they can improve in the future. It is worth noting that not only their tutors’ feedback but also feedback from their friends influences their learning. When asked whether feedback from their friends improves their work or performance, 55% (113) of the 206 participants indicated yes, only 27% (55) said no and 18% (38) of the respondents said they did not know whether their friends’ feedback improved their learning. This means that more than half of them said that their peers’ feedback positively impacted upon their performance.

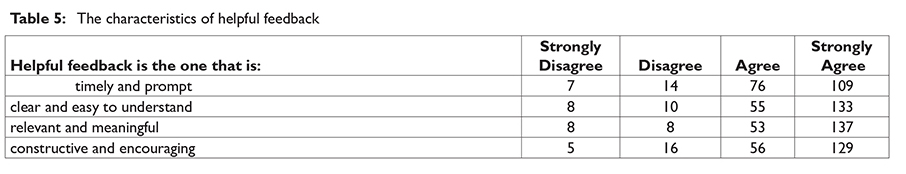

Besides students’ stimulus, e.g. their eagerness to read tutor feedback in order to know whether their work is good or not and where/how they can improve their learning as mentioned, there are other factors which considerably influence student response to tutor feedback. This is related to the quality of tutor feedback. Drawing on a number of scholarly accounts and guidance on tutor feedback, e.g. Weaver (2006), Aston University (2009-10), Juwah et al. (2004); Burke and Pieterick (2010, pp. 75-77), this research identified four main elements that constitute effective or helpful feedback, i.e. the feedback that helps students reflect on and redirect or improve their learning, and asked respondents to give their views on those criteria. As shown in Table 5, most of them agreed and strongly agreed that helpful feedback is the one that is timely and prompt (185 responses or 90%), clear and easy to understand (188 or 91%), relevant and meaningful (190 or 92%) and constructive and encouraging (185 or 90%).

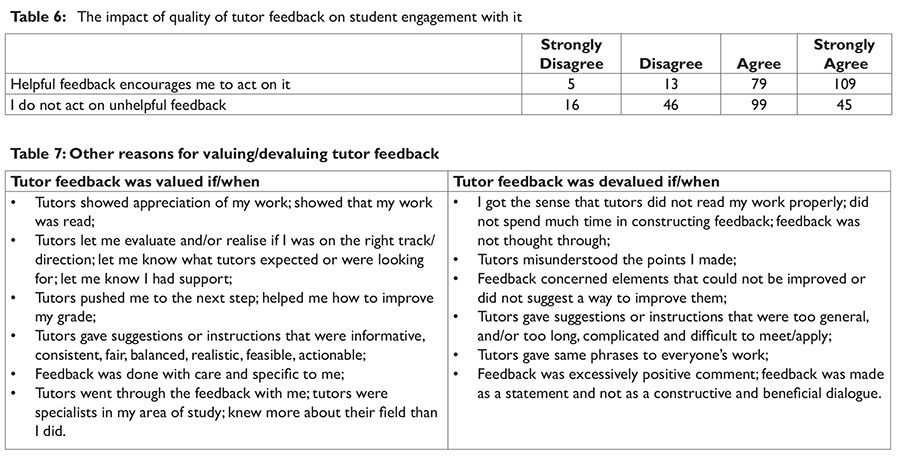

The author then sought to explore whether the quality of tutor feedback affects student response to tutor feedback. Based on the responses to the questionnaire, it is evident that while helpful feedback makes students value it and, consequently, engage with it, unhelpful feedback, i.e. late, unclear, irrelevant and unconstructive, hinders their engagement with it. As illustrated in Table 6, 91% (188) of the 206 respondents indicated that helpful feedback encouraged them to act on it. In contrast, only 30% (62) said that they acted upon unhelpful feedback.

The results of the survey also showed that positive feedback encourages students to learn whereas negative feedback often demoralises them. In fact, 35% (72) and 55% (113) of the 206 participants agreed and strongly agreed respectively with the statement that positive feedback boosts my confidence and encourages me to learn. In contrast, 34% (70) of the respondents agreed and 20% (37) strongly agreed with the statement that negative and critical feedback demoralises me and puts me off.

The responses to the open question also strongly supported the view that whether students are responsive or indifferent to tutor feedback significantly depends on its quality. Actually, most of those who answered the open question, i.e. to name three reasons that make them value feedback and three others that make them devalue feedback, said that they valued tutor feedback if it was timely, clear, relevant, and constructive and devalued it if it was late, unclear, irrelevant, and discouraging even though they phrased their answers differently. Many of them also said they valued feedback if it was positive and devalued it if it was too negative. For instance, a first-year student said she valued tutor feedback “if it guides, encourages and motivates me to learn” and devalued it “if it is unhelpful, negative and vague”. Similarly, a second-year respondent stated that he valued the feedback that was “constructive, meaningful and motivational” and devalued the one that was “destructive, late and irrelevant”. A third-year participant appreciated the feedback that was “positive, constructive and relevant” and did not like that one that was “negative, unconstructive and irrelevant”. A fourth-year student said he valued the feedback given by tutors “if it helps get a better grade, improves confidence and improves knowledge” and devalued it if it was “late, difficult to understand and irrelevant”. An MSc respondent mentioned that he valued tutor feedback “if it helps me improve my work, encourages me to learn and provides reflection upon my own work” and disliked it “if it is unconstructive, short and discouraging”. A PhD student indicated that she valued feedback “if it provides ways for improvement, if it is positive and constructive” and devalued it “if it is highly critical, unconstructive and late”.

There were other important factors making students value or devalue tutor feedback (see Table 7). Some participants also mentioned that the tutors who gave the feedback and the environment in which feedback was given also affected their reactions to tutor feedback. For instance, one respondent said that she valued feedback if she respected the tutor who gave it and devalued it if she did not respect the tutor.

To sum up how the quality of tutor feedback influences student reactions to it, it is worth referring to the answer of a PhD student to the open question. According to him, he valued tutor feedback “[i]f a tutor knows how to give feedback”, because tutor feedback “can be the single most productive tool in learning; we learn more from our own mistakes than others’ mistakes”. In contrast, he did not value tutor feedback “if a tutor does not know how to properly give feedback”. In his view, “[t]utors should help us to learn, not just mark”.

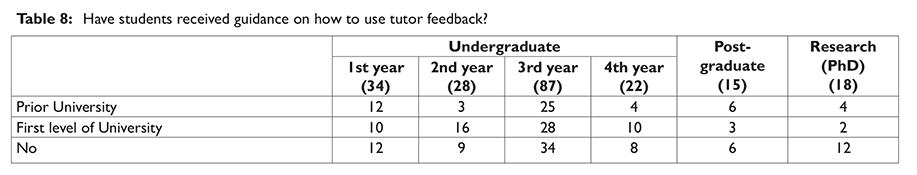

The third issue this study seeks to address is whether students have received guidance on how to use tutor feedback, whether that guidance (or lack thereof) affects their learning in general and their confidence in using tutor feedback in particular. When asked whether they had received guidance on how to use tutor feedback, of the 206 respondents, 125 (61%) indicated they had received it (either prior to University or during their first year at University) and 81 (39%) said no (see Table 8). This is significantly higher than the finding of a study undertaken by Weaver (2006, p. 389), which shows that “50% of students believed they had not received guidance on how to read and use feedback”.

Among those who had received it, 100 (81%) said that the guidance they had received improved their performance. Only nine of them (7%) indicated no and 14 (12%) said do not know. With regard to the 81 respondents who had not received guidance on how to use feedback, 37 (46%) said that such a lack of guidance hindered their learning, 21 (26%) said no, and 23 (28%) indicated do not know. Judging by these results, it is clear that the advice on how to use feedback the students had received considerably enhanced their performance or their learning whereas the lack of that guidance hindered their learning.

When asked whether they were confident in using tutor feedback, of the 206 respondents, 40 (20%) indicated very confident, 130 (63%) confident, 29 (14%) unconfident and 9 (3%) very unconfident. Overall, about 83% of those questioned were confident in using tutor feedback whereas only 17% lacked that confidence. This finding is noteworthy because in her study, Weaver (2006, p. 384) finds that between 21% and 41% of students lacked confidence in their understanding of a number of comments made by tutors. Moreover, it shows that, in contrast to the argument made by some scholars, e.g. Higgins (2000), Lea and Street (2000), Higgins, Hartley, and Skelton (2002), Orsmond, Merry, and Reiling (2005), that students are unable to interpret and use tutor feedback, most of the participants in this survey were confident in utilising it. In comparing the results of the responses, the survey also found that the more advanced participants in their study were, the more confident they were in using tutor feedback even though that gap was not so huge. For instance, 79% of the 34 first year respondents said they were confident in using tutor feedback (8 very confident and 19 confident), 86% of the 22 final year students said they were confident (4 very confident and 15 confident), and 89% of the 18 research participants indicated they were confident (8 very confident and 8 confident).

Another significant finding of this study is that the guidance on how to use tutor feedback the students had received impacted upon their confidence in using it. Of the 125 respondents who had received the guidance, 27 (22%) said they were very confident, 88 (70%) confident and only 10 (8%) unconfident in using the feedback given by their tutors. None of these respondents indicated they were ‘very unconfident’. In contrast, among the 81 participants who had lacked the guidance, 11 (13%) indicated they were ‘very confident’, 42 (52%) ‘confident’, 21 (26%) ‘unconfident’ and 7 (9%) ‘very unconfident’. In other words, while 92% of those who had been given the guidance on how to use tutor feedback were confident in using it, only 65% of those who had lacked that instruction felt confident in utilising it.

Finally, yet importantly, the results of the survey also reveal the advice on how to use tutor feedback affected student reactions to tutor feedback, especially those who were at the early stage of their university studies. Only 67% of the first-year respondents who had not received the guidance acted on tutor feedback whereas 83% of their peers who had received it acted on tutor feedback. Similarly, 67% of the second year respondents who had not received the guidance acted on feedback while 79% of their peers who had received the guidance acted on tutor feedback. In contrast, 92% (11 of 12) of research students who had not received the guidance acted upon their tutor’s feedback and 100% (6 of 6) of their peers who had received it acted on the feedback provided by their supervisors.

Three important points can be drawn from the findings of the survey. First, scholars and practitioners in higher education may be right to argue that numerical/quantitative grades/marks are more important to students than tutor feedback or qualitative comments. Yet, this does not mean that students ignore their tutor’s feedback as some of them suggest. Indeed, in contrast to the arguments made by Ding (1998), Ecclestone (1998), Wojtas (1998), and Fritz, Morris, Bjork, Gelman, and Wickens (2000), the findings of this study show that most of the students surveyed highly regarded tutor feedback, always read and always acted on it. This also means students actually used the received feedback and put it into practice. Moreover, as demonstrated by the research results, they valued and used it because not only did tutor feedback enable them to know what they had achieved but it also helped them to improve their future learning. In other words, the research results clarify very well the first set of research questions, which focused on whether students really value their tutor feedback and why tutor feedback is of importance to them. Overall, it is apt to say that the argument – or, more exactly, the perception – that feedback does not work or that “students do not ‘bother with’ feedback” (Weaver 2006, p. 391) is questionable.

Second, and related to the second proposed research question, while students respond to tutor feedback, the extent to which they act on it depends on a number of factors and one of these is the quality of tutor feedback. The more helpful tutor feedback is the more students act upon it. More precisely, as illustrated by the findings of this study, the feedback that is timely, clear, relevant and constructive radically enhances student response to it, whereas the feedback that lacks those qualities significantly prevents them from acting on it. Furthermore, the positive/negative feedback also plays a key role in encouraging/discouraging students to act. Many respondents, including research students, said they did not value feedback that was highly critical. In listing the reasons that make her devalue tutor feedback, a PhD candidate said she was “put off by negative feedback, though it is helpful”. Yet, as noted, one respondent indicated she did not like extensively positive comments as feedback. Thus, tutor feedback should be balanced between praise and criticism as a number of participants of the survey said. Neverthess, taken as a whole, helpful and positive feedback encourages students to engage with it whereas unhelpful and negative feedback tends to discourage them to respond to it. In a nutshell, the point made here is that student engagement with or disengagement from tutor feedback is significantly influenced by the nature/quality of tutor feedback, and such a finding is worth noting because research on student engagement with tutor feedback often ignores this. For instance, in their study, Price, Handley, Millar, and O’Donovan (2010, p. 280), while arguing that student engagement with assessment feedback is not entirely the responsibility of students, they maintain that “engagement is part of (and influenced by) a wider process involving others inside and/or outside a community of practice”. In other words, they do not look at the impact of the quality/nature of tutor feedback on student reactions to it.

Third, the advice on how to utilise tutor feedback that students have received is another influential factor that shapes their learning in general, their confidence in using tutor feedback and their reactions to it. In fact, as informed by the results of the survey, those who have been given instructions on how to use tutor feedback are better at improving their learning, have more confidence in using it, as well as are more likely to act upon it than those who have not received that instruction. This supports well the finding of Weaver (2006, pp. 389-390), which shows that the guidance on how to use feedback affects student response to it and the argument made by scholars, e.g. Chanock (2000) and Weaver (2006), that students need advice on using tutor feedback (Orsmond et al., 2013, p. 241). This third point answers very well the third proposed question of the study.

From what has been discovered and discussed, although tentative, this study wishes to highlight a number of practical points that tutors should take on board in order to enhance their students’ learning. The first among these is that providing feedback is not a waste of time. On the contrary, it is an effort that is worth it because it plays a crucial role in student learning and development, as a great number of scholars and practitioners in higher education, e.g. Hattie, Biggs, and Purdie, (1996), Hattie and Jaeger (1998), Hounsell (2003), Smith and Gorard (2005), Race (2007), Irons (2008), and Shute (2008) hold. More importantly, as the findings of this study illustrate, students actually value the received feedback and put it into practice. The practical implication of this finding is that tutors should not assume that students are not interested in their feedback and, consequently, not provide them with feedback or only do it infrequently and scantily. Instead, they should regard their feedback as central to student learning and, accordingly, offer their students sufficient and effective feedback. More precisely, in order to enhance student learning in general and boost their reactions to feedback, tutors should offer them feedback that is timely, clear and easy to understand, relevant and meaningful, constructive, and encouraging.

Furthermore, their comments should be balanced because remarks that are too negative and critical could decrease students’ confidence and, consequently, make them disengage from feedback. It is also vital that they should give students instructions on how to use their feedback because such guidance significantly determines students’ confidence in using their feedback. As shown, 61% of those surveyed in this study had received advice on how to use tutor feedback, which is much higher than the proportion found by Weaver (2006) in her study. Yet, 39% of those questioned did not receive that guidance. Therefore, instead of thinking that “their feedback comments were transparent in their meaning and import, or that students would know how to remedy any shortcomings identified” (Hounsell, McCune, Hounsell, & Litjens, 2008, p. 56), they should give their students, especially those who are in the early stage of their higher education, advice on how to interpret and utilise their feedback.

In summary, qualitative research, i.e. interviews with students, and/or a study on tutor perspective on feedback may be needed in order to further or validate the findings that this study has generated. Yet, the results offered by the survey on 206 students from different disciplines, schools, and levels of study at Aston University, shed an important light on the topic of tutor feedback in higher education, notably student perceptions and reactions to tutor feedback. Indeed, they demonstrate that students – or, at least, most of them – value tutor feedback and take it seriously. In other words, they use it and put it in practice. Given that, tutors should also take time and make the effort to offer them feedback. Furthermore, the nature or quality of feedback matters because whether and the extent to which students engage with feedback depends significantly on its quality. Therefore, to encourage their students to act upon their feedback and, consequently, to improve their learning, tutors should offer them helpful feedback – the one that is timely, clear, relevant, and constructive. Finally, students will be better equipped to engage with their feedback and, subsequently, will be more likely to enhance their learning, if tutors give them advice on using it.

Dr. Loc Doan holds a PhD in International Relations from Aston University and is currently working as a Research Fellow at the Global Policy Institute, London. He completed the Aston Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education in 2012 and a Post-graduate Certificate in Professional Practice in Higher Education at Aston University in 2013. He is a Fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy.