Edgy humour in the classroom: a case study

of risks and rewards

Mark Carver

University of Cumbria, UK

Introduction

Teachers looking to use humour in their pedagogy will find guidance and evidence lacking. The debate regarding the use of humour in education had its prime in the 1970s, and by the 1980s the debate was largely over. In many ways, it never got going: literature reviews found there to be a “dearth of material” (Baughman, 1979, p. 29), with the topic “strangely neglected” in research (Powell & Andresen, 1985, p. 79). The legacy has been reviewed as largely anecdotal, and often highly polemic (Bryant et al., 1980; Shatz & LoSchiavo, 2006). Combined with what now seems an overzealous attempt to “take humour seriously” (Durant & Miller, 1988) and overstate the importance of experimental and empirical results, the combined literature has served to leave “both the study and practice of humour outside of the classroom door” (Nilsen & Nilsen, 1999, p. 34). Despite attempts at drawing the literature together (most recently Banas et al., 2011), it remains “widely scattered, both in space and time” (Martin, 2007, p. xiii).

The positivist tradition is equally difficult to shake off, with quantitative and experimental methodologies remaining highly dominant. Teslow (1995) summarised the dilemma neatly: most research in the field is limited, outdated, un-replicated, and has produced only mixed results. This determination to prove humour’s effectiveness continues to give studies a polemic tone which tends to overstate the positives (e.g. Ogbolu & Abbey, 2012).

Where humour has been consistently shown to improve the educational experience is in student satisfaction and enjoyment ratings, particularly at university level (e.g. Berk, 1996; Wrench & Punyanunt-Carter, 2008) but also in professional training (Ulloth, 2002) and at school level (Hurren, 2005). This approach stresses immediacy in the teacher/learner relationship, and reminds teachers that teaching should be fun for the teacher too if enthusiasm is to be effectively shared (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011). Humour’s impact on satisfaction ratings has even been so influential that it contributes to debate regarding the “Dr. Fox effect” whereby a charismatic lecture devoid of content can seduce students into giving positive evaluations of learning (Naftulin et al., 1973; Neath, 1996).

Student satisfaction increases may, however, simply not be worth the risk if there is no accompanying learning gain, and using humour comes with words of caution even at university level (Bryant et al., 1979; Powers, 2005). Such words of caution are particularly the case for humour which has the potential to offend. In the research literature, Freud’s term “tendentious” (Freud, 1928) tends to be used to refer to such humour. This encompasses humour which has aggressive or sexual undertones, which might more commonly be described as dark humour, black humour, or edginess. In this study, “potentially offensive” and “edgy” are used for clarity as the term tendentious seems uncommon outside of humour research.

The fine judgement of risk and reward has yet to be explored in the research literature, yet is crucial for teachers looking to make those judgements for themselves so that they do not have to rely solely on their own instincts or a loose notion of common sense. This study aims to partly address this gap, and suggest future benefits of action research by evaluating outcomes from a mixed-methods perspective.

Methodology

Understanding humour as an emotional response (Ruch, 1993), rather than a cognitive one, is a key premise to the methodology of this study and is an approach which “many scholars have failed to realise until quite recently” (Martin, 2007, p. 9). Rather than looking for specific and statistically demonstrable learning gains in recall and cognition tests, the ideas of emotional intelligence and learning climate (e.g. Mortiboys, 2005) inspired a mixed-methods approach in an attempt to capture what Martin describes as the “sheer elusiveness” of humour research (Martin, 2007, p. 28). The study was therefore designed so that:

- The teacher would be free of any restrictions or self-editing behaviours

- Parents, students and school management would be required to opt-in to show their support for a novel and potentially risky approach

- Findings would be allowed to emerge from the free-coding of a range of rich data

- Results could be presented as a combination of qualitative, quantitative and anecdotal data

Site selection

In an attempt to explore the complex and subtle responses to teaching with humour and how data collection can attempt to capture such information, a five-week intervention was designed to examine the idea in an extreme case in a primary school’s literacy hour. The teacher’s main priority was therefore given over to the use of humour with no restrictions on taste or appropriateness: that is to say, a very liberal approach was taken to notions of common sense. Voluntary and informed consent was therefore very important for this study, as this untested idea represented a degree of risk. Consent was gained from sending letters to local primary schools, inviting them to opt in to the research and detailing the ethical procedures for the study approved by Lancaster University.

When the school was chosen, parents of the class were given information about the study and offered the choice of opting in or continuing with their regular class teacher. It is noteworthy that all the parents opted in, some very enthusiastically, which can be taken as an early indicator of parental attitudes to risk and humour in the classroom. In a setting where parents are less supportive, teachers may feel pressure to find a less controversial balance in keeping with Bryant and Zillman’s (1989) conclusion that receptive students are crucial to the success of teaching with humour.

Site description

The school was chosen from four volunteers due to its enthusiastic response and geographical convenience. With approximately 100 pupils on roll, the class size of 21 was below UK average. The daily literacy hour of the Year 6 class was chosen, and so students were aged nine and ten. Performance in literacy assessments was slightly above average at 4b, with a range from 2c to 5b. Female students performed slightly stronger than males, no students had English as an additional language, and the proportion with special educational needs was slightly lower than average, with some mild dyslexia and hyperactivity conditions. Entitlement to free school meals was also slightly below national averages, although the area was by no means affluent.

The topic at that time was journalistic writing, which lent itself quite well to adaptation through the use of humorous material and being able to adapt jokes from topical television and radio comedies.

Data collection and analysis

A total of 26 lessons were recorded by video and analysed for student engagement. This was supported by weekly student questionnaires and analysis of students’ work. Student questionnaires asked students to rate how much they learnt from and enjoyed each of that week’s lessons on a simple ten-point scale, with the opportunity to make comments. A further questionnaire was given two weeks after the intervention ended, asking for general feedback and comments on the most memorable events. The analysis of students’ work used assessed writing tasks to gauge the extent to which students attempted their own humour and drew upon humorous events from the week.

For video recordings, measures recommended by Camic et al. (2003), such as an unmanned setup and strictly limiting the video’s use to the aims of the study (rather than, for example, behaviour management) were employed to help students forget about the camera. Atlas.ti was used by two raters to code each lesson, with comparison and discussion used for moderation. Codes categorised each humorous incident as (i) safe, potentially inappropriate, and definitely inappropriate humour; (ii) successful and unsuccessful; (iii) related or not related to the academic content.

The first category was taken as a professional judgement, and very few cases of disagreement were found between the two teachers rating the videos. Some examples may be useful for those interested in analysing their own humour use. An example of safe humour was taken from reviews of a reality television show in which the teacher graded student work out of a million percent, a format which was revisited for football match reports graded out of 110%. Examples in this category tended to be rather silly or whimsical, such as the teacher pretending to like the latest pop groups and claiming to be “cooler” than the pupils.

The reality television review also gave an example of potentially inappropriate humour as the teacher described the corresponding national curriculum levels to the unusual grading system: “if you got 700,000 then that’s about a level 5, and 500,000 is about a level 4. If you got less than that, then you’ll need to have a dying relative to make it through, or use your VCOP pyramids to improve it.” Discussion of this example focussed on the “potentially” element of the category, where the joke would have been avoided if the teacher knew any pupils had terminally ill relatives, in which case he might have substituted “sob story” for “dying relative”. Other examples in this category included activities which could be difficult to justify out of context by imagining how a complaint from a parent would be handled, such as an activity teaching the use of pre-modifying adjectives which included “drug-addled”, “alcoholic”, and “chart-topping paedophile” as options, alongside a tangential discussion of the value of “alleged” in newspaper reports illustrated with a clip from Have I Got News for You.

The other label, ‘definitely inappropriate’, was only applied to 14 examples of humour use, and was understood as humour which could be expected to offend a general audience. Rather than being potentially offensive depending on context, as in the previous classification, in these instances the lack of offence would depend on suitably judging the context. An example included in this category was the teacher encouraging a student to vary intonation when reading aloud by commenting, “So you could read it in that style, like someone learning to read. Come on, try it again, give it a bit of feeling.” In this case, the pupil laughed and obliged, but it was a moment where raters thought that a different reaction could have led to a difficult situation. Keeping this as a relatively limited classification did lead to a rather large middle group of potentially offensive, which could be improved upon in future studies by seeking a more limited operational definition.

The second categorisation, successful or unsuccessful, was initially problematic as a professional judgement, and so inspiration was taken from the four-point scale used by Masten (1986). This improved reliability, but still led to disagreement. Finally, only the highest point of Masten’s scale (vocalised laughter) was used for coding student responses as positive. This inevitably reduced the number of incidents categorised as successful by not including such responses as smiling, but was chosen for its simplicity as laughter is a relatively straightforward way in which teachers can gain feedback from humour use. The remaining category was unproblematic for coding by relating comments to the stated learning objectives for that class.

Whilst the data lent itself to statistical descriptions, the study was intended to explicitly draw on qualitative judgements in order to strike a balance between the positivist and anecdotal extremes previously criticised as dominating the research literature. Results are therefore reported and interpreted with both quantitative and qualitative data in order to show the relative merits and limitations of each, and thereby make the case for more mixed-methods and naturalistic research in this area.

Results

Features of humour events

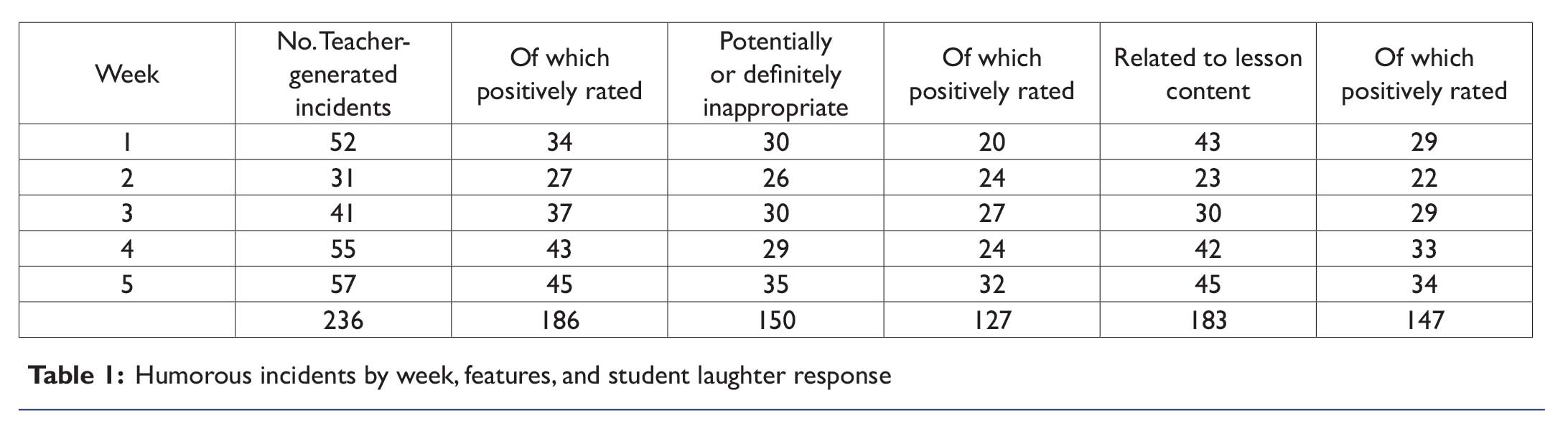

Across 26 lessons averaging 55 minutes each, humorous incidents produced by either the teacher or students occurred 369 times for an average duration of 14 seconds, thereby accounting for 6.2% of learning time. The 236 (64% of total) teacher-generated humorous incidents were rated as safe (36.4%, n=86), potentially inappropriate (57.6%, n=136), and definitely inappropriate (5.9%, n=14). In total, 186 (78.8%) of these were positively rated (i.e. the majority of students laughed). Humour related to the content of the lesson accounted for 183 (77.5%) of those incidents, of which 147 (80.3%) were positively rated. The codings are summarised by week in Table 1.

Should humour be edgy?

Using the query tool in Atlas.ti, comparisons can be made between different coded instances. Reaction to potentially and definitely inappropriate humour found agreement with the tendency for edgier humour to be rated funnier (Gruner, 1997), with 84.7% (n=127) of such humour gaining a positive response compared to 68.6% (n=59) for positive responses to teacher-generated humour which was judged to be safe. This may be of interest to teachers who are finding that their humour is not being well-received, as their attempts may be playing too safely. Weekly evaluations further supported the idea that humour which was coded as edgy was associated with positive evaluations for enjoyment and learning content of lessons.

Similarly, the teacher and observer reflected that the teacher enjoyed the lessons much more than normal and described a “buzz”. Given recent teacher attrition trends (Borman & Dowling, 2008) and the value of humour as a coping strategy in stressful situations (Lefcourt, 2001; Lefcourt et al., 1997), this may be reason enough to try to find ways to make lessons more enjoyable, even if it is simply a case of teachers amusing themselves. There may be a risk here that such feelings encourage the teacher to perform rather than be student-centred, but this was not found to be the case in any of the observations in this study.

Should humour be content related?

Using the same tools, the 183 cases of content-related, teacher-generated humour were positively received 147 (80.3%) times. This compared to 37 (68.5%) of the 54 teacher-generated humorous incidents which were not content-related. This difference could indicate that humour for its own sake will be less positively received, while teachers should take care to ensure that their humour is relevant to the topic being learnt. This might be explained by such humour appearing contrived, but this is not borne out by the codings: 35 of the 37 positive ratings for non-content related humour were also coded as spontaneous, compared to 91 out of 147 positive ratings for content-related humour. This would indicate that there is a case to be made for students reacting more positively to content-related humour simply because it is related to the content being studied. Interestingly, potentially inappropriate humour which was also content-related shows an even stronger relationship at 98 positive reactions out of 111 events (88.29%), compared to safe content related humour at 50 out of 73 (68.5%).

The qualitative data from student evaluations, teacher reflections and written lesson observations was interesting in that it made very few distinctions between relevant and irrelevant humour use. As a factor which teachers and students may both miss in reflective accounts, the simple statistical relationship between content relevance and laughter could indicate the subtlety and elusiveness of evaluating humour use. It also suggests that teachers evaluating their own humour use should keep some account of which humour events gain laughter, rather than simply relying on reflective feedback, as this extra data collection method can reveal interesting differences in the features which are positively received by students.

How can students’ use of humour contribute to the learning climate?

After the initial analysis, further coding was conducted to see if the way students used humour had been affected by the intervention. A relationship was found between the quantity of teacher humour in a lesson and the quantity of student humour in a lesson, with a Pearson correlation of .515 (p=.012) indicating that greater quantities of teacher humour encouraged greater quantities of student humour.

Where the relationship was not found to have a statistically significant relationship was in change over time, suggesting that students did not become increasingly prolific in their use of humour but continued to take their lead from the teacher. The explanation that students took a cue that being humorous was safe and welcome in the learning environment is further supported by the correlation being stronger for potentially inappropriate teacher humour (.612, p=.002), particularly for student-generated humour which might be regarded as potentially inappropriate (.726, p<.001) and concept-related (.634, p=.001). Again, neither of these trends changed over time but rather in relation to the modelling provided by the teacher in that lesson. Learning climate might not therefore be something which is built over the long-term, but something which – at least to some extent – is re-established in each class.

Interestingly, all the qualitative data referred to a changing attitude over time: students expressed greater confidence in sharing their own humorous ideas, an increased awareness that more content-relevant humour would be appreciated, and both the teacher and observer commented on how students were generating more – and more desirable – humour. This is not to discount the qualitative data in favour of statistics, and can be taken to reflect the more collaboratively constructed elements of a learning climate. Students and teachers were able to articulate shared values related to humour production, even though such values were not reliably indicated through observed behaviour. With only five weeks of data, this idea cannot be fully explored.

Were there any recall or cognitive benefits to the use of humour?

Student evaluations of their own learning showed a strong link between their ratings for enjoyment of the lesson and how much they felt they learnt (Pearson r = .923, p<.001). This correlation may be partly due to the data collection instruments, as 157 of the 384 pairs of scores (41%) were identical. However, the link was further supported by final evaluations in which all but one student agreed with statements linking the two features. Both teacher and observer observations reflected on the increased enjoyment and attention and that learning had been effective at either the “good” or “outstanding” level using the observation framework, but not that learning of humorous parts of the lesson had been learnt any differently. Instead, comments tended to focus on the learning climate and students’ attention and motivation throughout the whole lesson.

Some cognitive link was suggested by analysis of student work which showed a tendency, particularly for male students, to remember and use humorous examples from the week in their Friday writing task. Overall, however, the data supported a view that humour’s greatest contribution was to the general learning climate rather than in focussing attention on any particular learning points. This may be in part due to the skills-focus of the subject (English), and research in subjects emphasising factual recall may find greater indication of the “attention” effect of humour (Davies & Apter, 1980).

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that the effects of freely using humour in the classroom are that it generates greater interest and enjoyment for both teacher and students, encourages content-relevant humour production from students, and leads to greater satisfaction and perception of learning from students. In this respect, it is difficult to disentangle humour use from increased risk-taking and spontaneity in a learning climate: an untested hypothesis may well be that humour is simply a vehicle to achieving a learning climate in which both risk and spontaneity are rewarded.

For educators intending to experiment with humour and reducing their boundaries, this study has indicated the potential for students, parents and schools to support such approaches. Provided that humour is related to the content of the lesson and is not deliberately hurtful towards anyone in the group, this study suggests that there is minimal risk in using humour which might initially seem unsuitable for the classroom. Where parental and managerial support is lacking, change may have to come more slowly.

In terms of methodology, this study indicates that tracking laughter feedback is a relatively straightforward means of gaining useful quantitative data which helps to capture some of the elusiveness in the study of humour. Student evaluations and lesson observations similarly provide a useful way of evaluating how students react to their learning environment in more generalised ways. Those interested in action research in this area would therefore be advised to adopt an approach which includes these data collection methods as a way of understanding the immediate and long-term effects in addition to the tacit and articulated effects.

The study therefore concludes that there is not only a need to continue to examine the role of humour in education, but in preventing over-cautiousness from limiting the potential for teachers to create an enjoyable learning climate which rewards share humour, risk and spontaneity. By seeing humour as contributing to other elements of learning climate rather than leading to any specific learning gains, the temptation to overstate the case for humour in education is removed. What this study has demonstrated is that, given the choice, parents and teachers are willing for learning environments to feature a wider range of humour than might previously have been thought. When using humour, teachers should attempt to make it relevant to the topic of the lesson and need not be afraid of taking risks and retaining some edginess to their humour rather than self-censoring. Peer observation and student satisfaction ratings suggest that the educational value of lessons is at least maintained, if not improved, by freeing the teacher’s creativity and natural humour. These simple relationships are presented as reason enough to encourage practitioner experimentation and action research.