Understanding and Supporting Triple

Transitions of International Doctoral

Students: ELT and SuReCom Models

Divya Jindal-Snape and Richard Ingram

University of Dundee, UK

Introduction

International doctoral students go through a triple transition, firstly of moving to a new country, secondly of moving to a new educational system with different expectations, and thirdly a different level of academic study which requires them to be independent. Previous research indicates that students going through any of these transitions can have problems leading to anxiety, loss of self-esteem and lowering of educational attainment (Jindal-Snape, 2010). These students are not only in a culture different to their own, they also have to deal with, sometimes implicit, rules and expectations of social and educational organisations, as well as dealing with all the problems of adjustment common to students in general.

Despite these obvious issues, only 16 studies related to international doctoral students were identified in a thorough review of literature that focussed on studies published from 1990-2009 (Evans & Stevenson, 2010). According to the authors, there were three aspects that influenced the students’ engagement with the doctoral programme; pedagogical paradigms, pedagogical practices and academic environments. A search conducted across the educational databases (e.g., ASSIA Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, British Education Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Cambridge Journals Online, Oxford Journals, SCOPUS) using key terms ‘doctoral students’ and ‘challenges’ yielded four papers that matched these terms; of which only two explored challenges, both faced by home doctoral students, and both focussed on academic and professional issues. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no published study that explores the transition of international doctoral students in the context of academic and daily life.

Recent empirical research that compared experiences of international and Irish home students, studying mainly on undergraduate programmes in one Irish university, found that despite high levels of social support, international students were experiencing high levels of sociocultural adjustment difficulties and psychological distress (O’Reilly, Ryan, & Hickey, 2010). There is evidence that those involved in science-based doctoral research have more in-built support mechanisms due to the nature of lab-based doctoral work (although Le and Gardner’s (2010) study found that Asian students still found it difficult to adapt in USA). The studies presented in this paper focus on students from social sciences, traditionally working on individual research projects and who might not have in-built opportunities of interacting with other students. Therefore, these relationships with supervisors and other students might become crucial to their adaptation.

Evans and Stephenson (2011) note that whilst the process of doctoral studies proves challenging to many students, there is a strong sense that students are able to identify positive life changing skills and experiences upon completion. According to Moores and Popadiuk (2011), this is an under-researched aspect of international students’ transition experience.

The purpose of this paper is to present two original models that can be applied not only to international doctoral students, but also to home doctoral students and other international students, to facilitate their transition. These are the Educational and Life Transitions (ELT) model and Supervision Remit Compatibility (SuReCom) model. The former explains the transition experiences of students as well as providing insight into how the experience can be improved, and the latter looks at how the gap between expectation and reality of the supervision role and remit can be reduced. These models are based on a small scale study that explored international doctoral students’ positive and negative experience of academic and daily life adaptation in the UK. This study aimed to fill the gaps in the literature and is the first study to provide an insight into, and recognition of, these triple transitions. The ideas behind the SuReCom model were also tested with some doctoral home students and their supervisors, to emphasise its applicability beyond the international students which we will briefly refer to.

This paper will first present the theories underpinning the two models, followed by data that led to the development of the models, and finally the two models. The paper has been structured in this way so that the readers can see the conceptual thinking and research behind the models before the models are presented.

Theories underpinning ELT and SuReCom models

Previous research has tried to understand transitions through the ABC model (Zhou, Jindal-Snape, Topping, & Todman, 2008), emotional intelligence (Adeyemo, 2007), and resilience theories (Jindal-Snape & Miller, 2008, 2010). This paper explores these further and embeds them in the proposed models.

The ABC model

Systematic research on international students started appearing after the 1950s, with a focus on social and psychological problems faced by them when moving to a new country (Ward, Bochner, & Furnham, 2001). Three contemporary theories, ‘culture learning’, ‘social identification’ and ‘stress and coping’ that are more comprehensive and see the individual as pro-active and responding to the environmental changes, provide a framework for the ABC model. These theories consider different components of response when individuals are exposed to a new culture – affect, behaviour and cognition. Zhou et al. (2008) brought these theories together within a broad theoretical framework, the ABC model, to better understand how international students might be adapting to change based on the affective, behavioural and cognitive (ABC) aspects of shock and adaptation. This ‘cultural synergy’ framework offers a more comprehensive understanding of the processes involved in the academic adaptation and acculturation of international students. However, in previous research around international students’ adaptation, a distinction has been made in the literature between psychological, socio-cultural and educational adaptation, and studies in these three areas have mostly been pursued separately. We believe these studies have therefore overlooked the multi-faceted key experiences of the students (Zhou et al., 2008) and most importantly have not considered the interaction between these aspects. Although studies exploring the pattern of educational adaptation of international students are few, some studies have suggested that problems relating to intercultural classrooms are mainly due to mismatched cross-cultural educational expectations (e.g., Jin & Cortazzi, 2006; Jin & Hill, 2001). There is also evidence that international students’ expectations prior to leaving their home country and the reality (whether educational or related to daily life) when they are in the new country can have an influence on their adaptation (Zhou et al., 2008).

Emotional intelligence

Mayer, DiPaulo and Salovey (1990) suggest that emotional intelligence consists of an individual’s ability to be aware of their own emotional reactions to various stimuli and their abilities to manage their responses to such stimuli. They suggest that this balance of awareness and control allows individuals to make decisions with increased clarity and confidence. In addition, they suggest that an ability to identify emotional responses in others is a key aspect of emotional intelligence. These abilities are further linked to an individual’s ability for empathic understanding and skills in communication. From these attributes it is argued that positive relationships and outcomes may flow (Goleman, 1995; Lishman, 2009). Emotional intelligence within the context of the supervisory relationship would help all participants to engage with the student experience at an academic, practical and emotional level. The data emerging from this study will reflect the emotional impact of adjusting to a new culture and the potential window of opportunity for the supervisory relationship to be a forum to explore, acknowledge and identify the emotional context of doctoral studies for international students. In any given relationships, emotional intelligence is a two-way process, and both supervisor and supervisee will bring their own skills and abilities to the relationship. This would seem to be reinforced by the assertions that emotional intelligence is an essential element of leadership (Goleman, 1995; Lindebaum & Cartwright, 2011) and educational attainment (Goleman, 1995). Reilly and Karounos (2009) undertook an international study of perceptions of effective leadership styles in industry and found that whilst certain emotional intelligence attributes such as motivation and social skills were valued globally, there were variances in the degree to which factors such as empathy and participation were valued. This provides a cautionary warning in terms of seeking to view ‘international students’ and the supervisory styles required as homogenous and consistent.

Resilience

Resilience theory underlines the protective and risk factors in an individual’s environment (Newman & Blackburn, 2002; Jindal-Snape & Miller, 2008). Wang (2009) found that resilience had the greatest impact on the adaptation of international graduate students studying in the USA. Lee, Koeske and Sales (2004), in a study conducted with Korean students studying in the USA, found that stress related to acculturation could lead to mental health problems. They also found that social support buffered the effect of stress on mental health symptoms. However, the buffering effect of support was mainly present when there was adaptation and acculturation in the context of the host nation’s language and interpersonal relationships. Therefore, there is a clear need for strong secure attachments and support networks at the time of this triple transition. The support network for international doctoral students might include their supervisors and other staff, their family and friends, and new friends they might make in the host country. These protective factors can also of course become the risk factors. Previous research has suggested that, due to differences in culture and language difficulties, international students might find it difficult to form new relationships in the host country (Zhou et al., 2008). Similarly, some of the mature students would either have left their families in the home country or moved with them. For those who come with their families, we should not forget the cumulative impact of their family’s transition. These students are not only going through their own transition, they have to support their families as well. Those who leave their family behind might again find the transition of being away from the family an additional difficulty that they have to deal with.

In conclusion, as mentioned earlier, transitions and significant life events often incur stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and the adjustments required of an international student adapting to a new environment both academically and culturally require support and management (Zhou et al., 2008). This is further emphasised by Evans and Stevenson (2011), who found that students perceived supervisory relationships to be the most critical aspect of support but find it difficult to attain this due to differences in supervisor/supervisee expectations. The aforementioned ABC model provides the backdrop to the supervisor/supervisee relationship along with the ability to make friends in the host country. The supervisory relationship involves three central facets; the student, the supervisor and the knowledge (Grant & McKinley, 2011). This pedagogical framework focusses the relationship on knowledge transfer and production, and the relationship’s function is to teach and co-create knowledge. This vision of doctoral supervision might fall short of embracing the ABC model and potentially neglects the holistic experience of being an international student. If we accept the wider remit for the doctoral supervisory relationship, then it is pertinent to consider the potential role and use of emotional intelligence within this relationship. Clearly, in order to apply emotional intelligence in a holistic supervisory relationship, it would be essential that permissions to explore personal and cultural issues are made at the outset of the relationship. However, educational systems and expectations of supervisor/supervisee roles can create barriers to this understanding. For example, the UK supervisors might expect the students to be independent and take ownership of their doctoral research; international students culturally might expect there to be an expert-novice relationship. This is not only to do with being from different cultures but also the difference between the educational stages.

Research findings underpinning the ELT and SuReCom models

Methodology

A mixed methods design was used to understand educational and life transitions through an exploration of the lived experiences of doctoral students in the social sciences, in University A in the UK. University A is based in a medium sized city (City A) with a multi-cultural population. Cost of living is reasonable compared to the rest of the UK.

This study used an online questionnaire to provide the students an opportunity to freely and honestly respond to the questions, as the online system does not store any personal information. All students were also invited to participate in follow up interviews or focus groups. However, only two students volunteered and a small group interview was conducted on their request.

Online questionnaires were made available to all the international doctoral social science students at University A. This was done to keep the disciplines similar as students studying, for example, in life sciences or medicine might have different expectations and experiences due to differences in the research environment. The questionnaire included a mix of closed questions with some space for comments as well as open questions where unlimited space was provided for a detailed response. The questions were based on themes identified through a thorough literature review, especially the ABC model with a focus on not only academic transition but also life transitions. A total of 22 international doctoral students responded to the questionnaire. The interview questions were open with ample opportunities for the participants to be involved in the discussion and to provide new ideas. Quantitative data were analysed using simple tabulation to explore relationships between variables. Qualitative data, which came from all 22 students through questionnaires and from two through interviews, were analysed using thematic analysis. The study was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee.

Results and discussion

Questionnaire participants came from 15 countries across Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America. There were 13 female and nine male participants. A total of 11 participants indicated that they were single, nine married, one divorced and one preferred not to say. Of the seven participants who indicated that they had been accompanied by family, five came with their partner and children, one with partner and one with child only. Due to the small sample size and no apparent trends based on the demographics, the findings have been presented without distinguishing on their basis.

Academic and daily life transitions

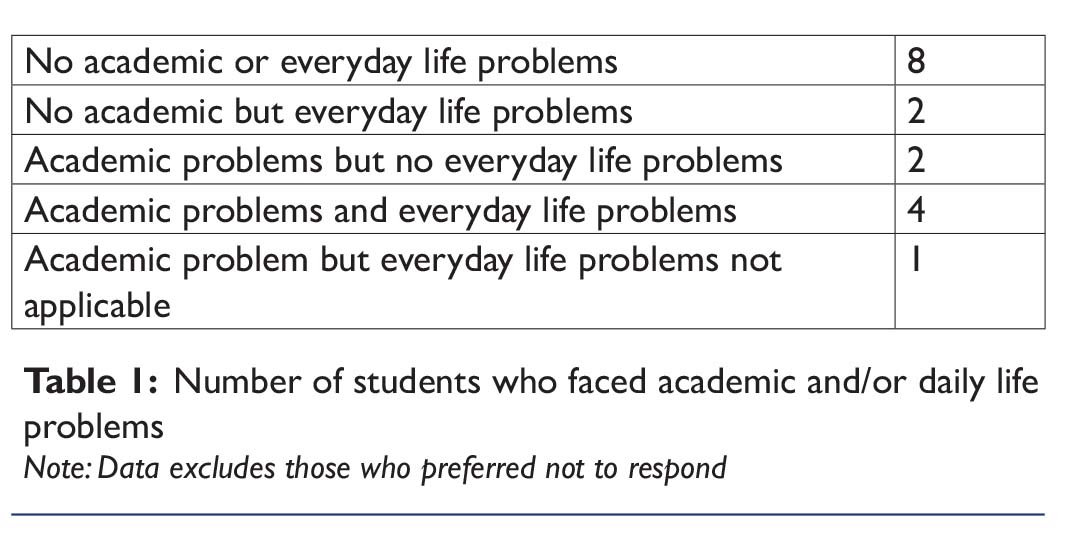

In response to statements about their experiences, 12 participants indicated that they had faced no academic problems, eight had faced academic problems and two chose ‘prefer not to say’. In terms of everyday life problems, 10 said they did not face any problems, eight said that they did, three preferred not to say and one said it was not applicable. Cross-tabulation suggests that, of the 12 who had faced no academic problems, two faced everyday life problems and two preferred not to comment (see Table 1). Similarly, of the 10 who said they did not have everyday life problems, two said they had academic problems. Interestingly, the same students did not face problems with both aspects.

It is possible that students were not comfortable indicating they had any academic problems to a staff member. Again, different students indicated problems with one aspect but chose ‘prefer not to say’ for the other. It raises the question of why they were happy to share one set of information but not the other. Is it that they themselves did not see a relationship between the two? Or it may also indicate that some students feel it is not appropriate to express their felt link between academic and everyday problems due to implicit constructs about what is relevant and permissible when talking about their doctoral studies.

Difficulties experienced in academic and daily life

The majority of students highlighted finance (n=10) to be the biggest problem, followed by finding accommodation (n=7) (perhaps also linked with financial issues) and difficulty in reading academic books and papers (n=5).

The qualitative data from the questionnaire and interview shed some light on the profundity and complexity of these challenges.

I lost 10 kilograms because of the pressures and difficulty to find food and had to look after my family and wife so this kind of affect makes me quite depressed – I think depression is the best word.

What emerged from the qualitative data from the 22 participants is a clear sense of the interconnectedness of issues such as financial problems and other issues such as isolation, health and family problems. Some of these factors such as suitable accommodation could be considered to be hygiene factors (Herzberg, 1966, cited in Jindal-Snape & Snape, 2006). If these are not met then the student will be dissatisfied regardless of what else is happening. However, of course, if these factors are met then it does not automatically lead to satisfaction with other aspects of academic and daily life.

From the quantitative data, it is not clear whether there is a link between the financial aspect and difficulties with their study. However, there is some evidence of this link in their qualitative data.

Financial problems. Because I have not so much time to work, so I can’t get enough money to pay the fee. If work too much then no time to study.

I face a little bit financial problems as my scholarship stipend amount is not enough for good residence and food.

However, not surprisingly, students who found it difficult to engage with academic papers, English language and expectations of being a doctoral student, were having problems with the doctoral study.

Language problems in academic life [was the biggest difficulty] … It is not a medium in majority of universities in ‘name of country’. Therefore, a usage of high level of English makes me feel stressful. However, an English support program provided by the university helps me a lot in this matter….

Writing is the most challenging part… the style of presenting arguments is different with what I have done before. In addition, I am thinking in my own language and translating it to English language.

Perhaps the six, who had faced no academic problems despite financial difficulties, might be more resilient if they were finding the academic work to be going well.

Interestingly, similar areas of difficulties were mentioned by those who were having problems in everyday life.

When I arrived… I faced a problem to communicate with my family in my home country. Then, getting basic needs became another problem. I went to several shops around… to get basic needs without using a public transport. Receiving many letters from local authorities and government is another issue for me. To sum-up we are still learning about culture!

Others also commented on difficulties with adapting to the difference in climate and missing their family. Certain issues such as finance, accommodation, and academic papers were causing difficulties to several students. Some seemed to have managed to overcome them, whereas others were finding them to be problematic in academic and daily life.

Enjoyable aspects of academic and daily life

When asked what aspect of doctoral study they were enjoying the most, 12 responded, with eight mentioning working with supervisors and staff as the most enjoyable, followed by aspects of fieldwork and creativity.

Supervision, because of the informal nature in which it is conducted and yet very thorough. The timely reply and quality comments from my supervisors.

Interaction with experts and staff in the university. They are supportive and ready to help me in solving a problem.

As is clear from previous transition research (Jindal-Snape, 2010), some students enjoy the challenge and opportunities that transition can bring. Data collected from participants in this study confirm this.

The very challenging academic structure and the ability to structure my own time because I had previously been a full time carer for my children and now I am in a full time PhD, which has required adjustment for everyone but I am thoroughly enjoying it and wouldn’t want anything else.

Similarly students gave examples of areas they were enjoying that related to their daily life.

Geographical situation. I love the seaside and I equally enjoy the lovely landscape…

I am living in the centre, so it is easy for me to get anything easily. And I like this city because people are quite nice and it is quiet and peaceful, good for study.

Support provided by the University for academic and daily life transitions

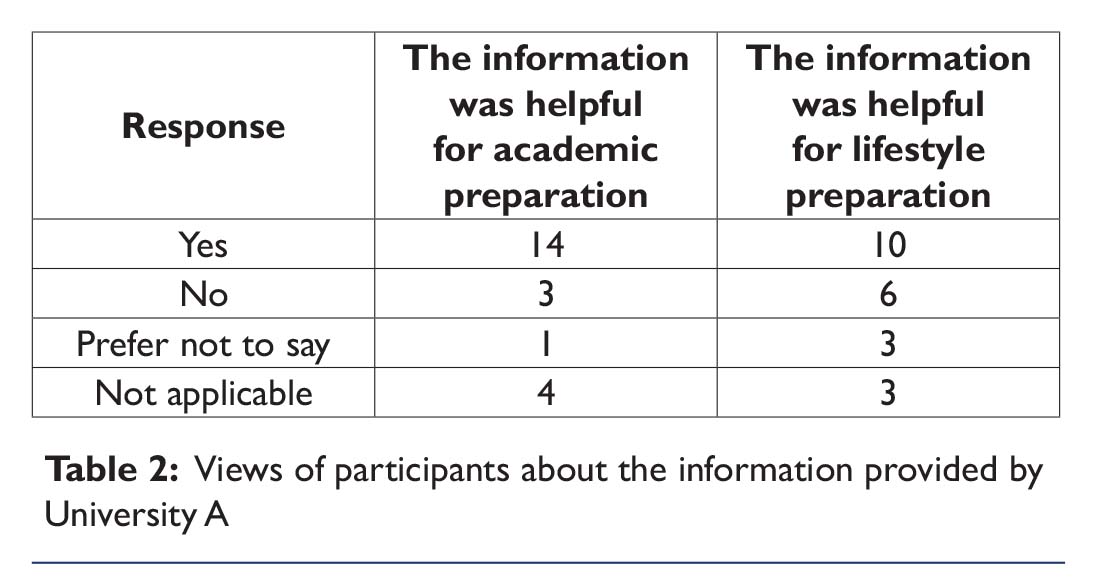

In terms of satisfaction with information provided by the University, irrespective of difficulties and problems with academic and everyday life, 14 said they were happy with information related to academic life, three said they were not, one chose not to state and four indicated that it was not applicable. In terms of information for lifestyle preparation, 10 were happy, six were not happy, three chose not to comment and three said it was not applicable (see Table 2).

This suggests that more students were happy with the information regarding academic preparation than lifestyle preparation. It also indicates that their university might have been better at providing information and support related to academic transition than that related to life transitions. Similar to Zhou et al. (2008) this emphasises the need to look at these aspects together and to provide holistic information.

Supervisor-supervisee relationship

This study highlights the issues that international doctoral students face. The participants drew connections between difficulties they experience in their daily life and the impact this can have on their academic performance and motivation. The emotional intelligence of the student and supervisor could facilitate the identification and exploration of the difficult issues. In keeping with the work of Mayer et al. (1990), it is important that supervisors are able to tune in to the emotional content of what their students are telling them and to be able to manage the emotions that this gives rise to. For example, it might be that the supervisor, who was cited as having a “packed agenda” by one student in this study, would feel a sense of irritation and pressure if difficult emotional issues competed with the core function of the supervision. If the supervisor can identify and manage this emotional response, then the interests of the student can be safeguarded.

The data suggests that the supervisory relationship often has at its foundation a clear delineation of roles that places the supervisor as the expert and the student as a learner. This is not wholly surprising or indeed inaccurate, but if the relationship is to take on a broader holistic remit, then the impact of these labels must be explored and acknowledged. This would facilitate the explicit use of emotional intelligence within the relationship rather than let the accepted power imbalance inhibit or implicitly dismiss the emotional content of the student experience. The aforementioned idea that supervision has a ‘core function’ is a crucial issue. If the supervisory relationship is to achieve a more holistic form than the tri-faceted knowledge based construct proposed by Grant and McKinley (2011), then it seems that the very essence of the relationship should be co-created between supervisor and student. This co-creationist approach not only allows for the wider issues to be permissible within the relationship, but builds in flexibility where this is not desirable for the participants. This echoes the suggestion from Reilly and Karounos (2009) that there will be variances between the expectations and needs of students at a cultural and individual level.

ELT and SuReCom models

Educational and Life Transitions model

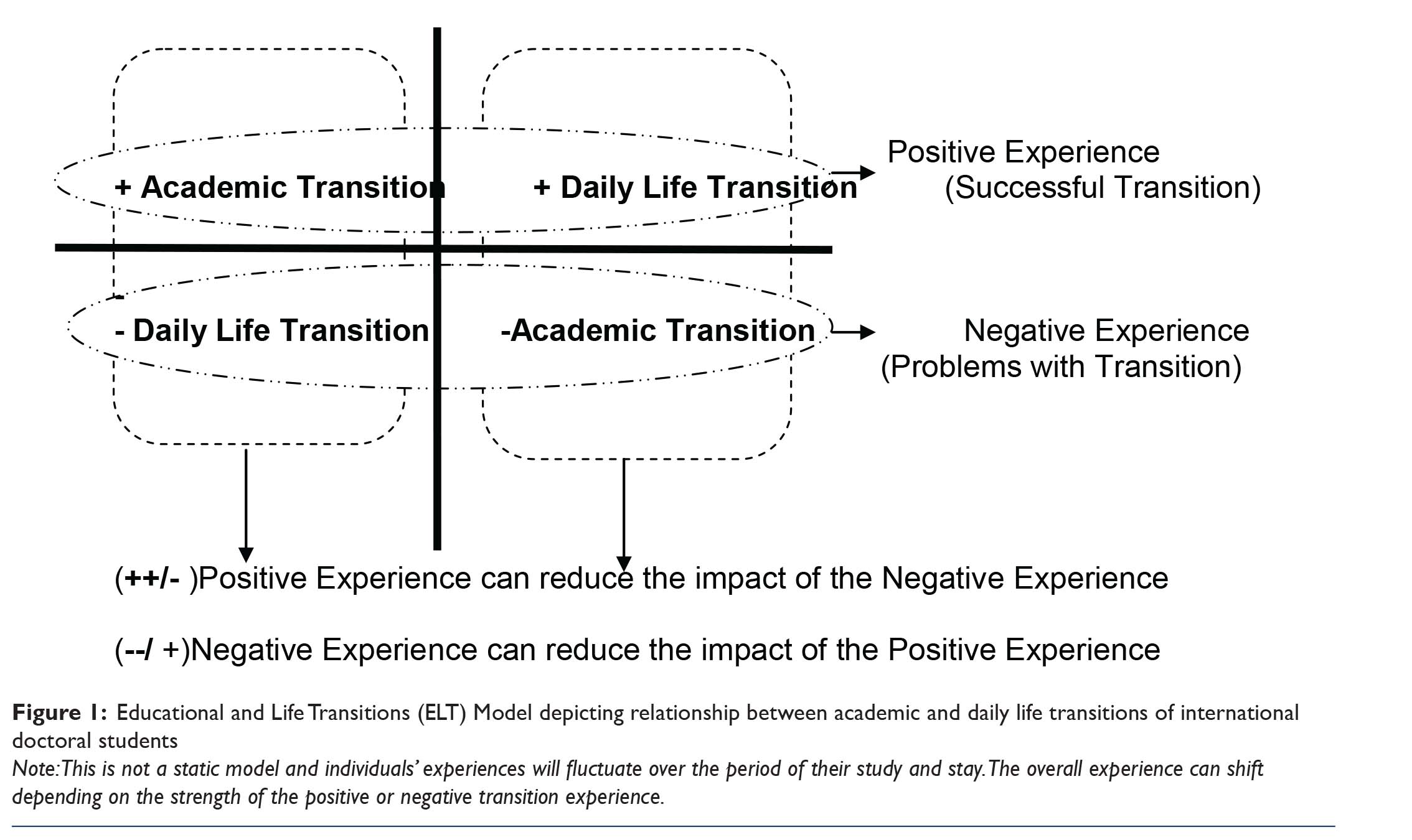

Similar to the vertical and horizontal transitions model presented by Pietarinen, Soini and Pyhältö (2010), it is clear that one type of transition can have an impact on the other transitions (Figure 1). However, it also seems that if the positive experience is stronger, it could act as a buffer against any negative transition experiences. For example, a student for whom the academic work is going really well (++) might find it easier to deal with any minor problems (-) with daily life transition. On the other hand if daily life problems are major (--) such as financial difficulties leading to problems in finding suitable accommodation, it might distract a student from studying effectively and lead to a downward spiral in terms of adapting to the academic environment.

It is possible that when students arrive in a new city the focus is on trying to adapt to daily life rather than academic life, and as they get into their research work, the focus might shift to academic adaptation. This will also be influenced by the transitions their families might be going through. This can shift in the second year and then back to the academic focus in the third year. This reinforces the ABC model and the need to keep considering the academic and daily life needs of the students, and resilience theory as it suggests that the protective factors can act as a buffer for any risks.

The ELT model can offer insights into how to increase protective factors. For example, the supervisors who are able to support the students well and build good relationships with them, or can create opportunities for the students to succeed socially or academically might be able to provide positive experiences that can act as a buffer against any other negative experiences. Similarly, by providing physical and mental space to link up with other students, the university staff might be able to create further support networks for the students.

The SuReCom model

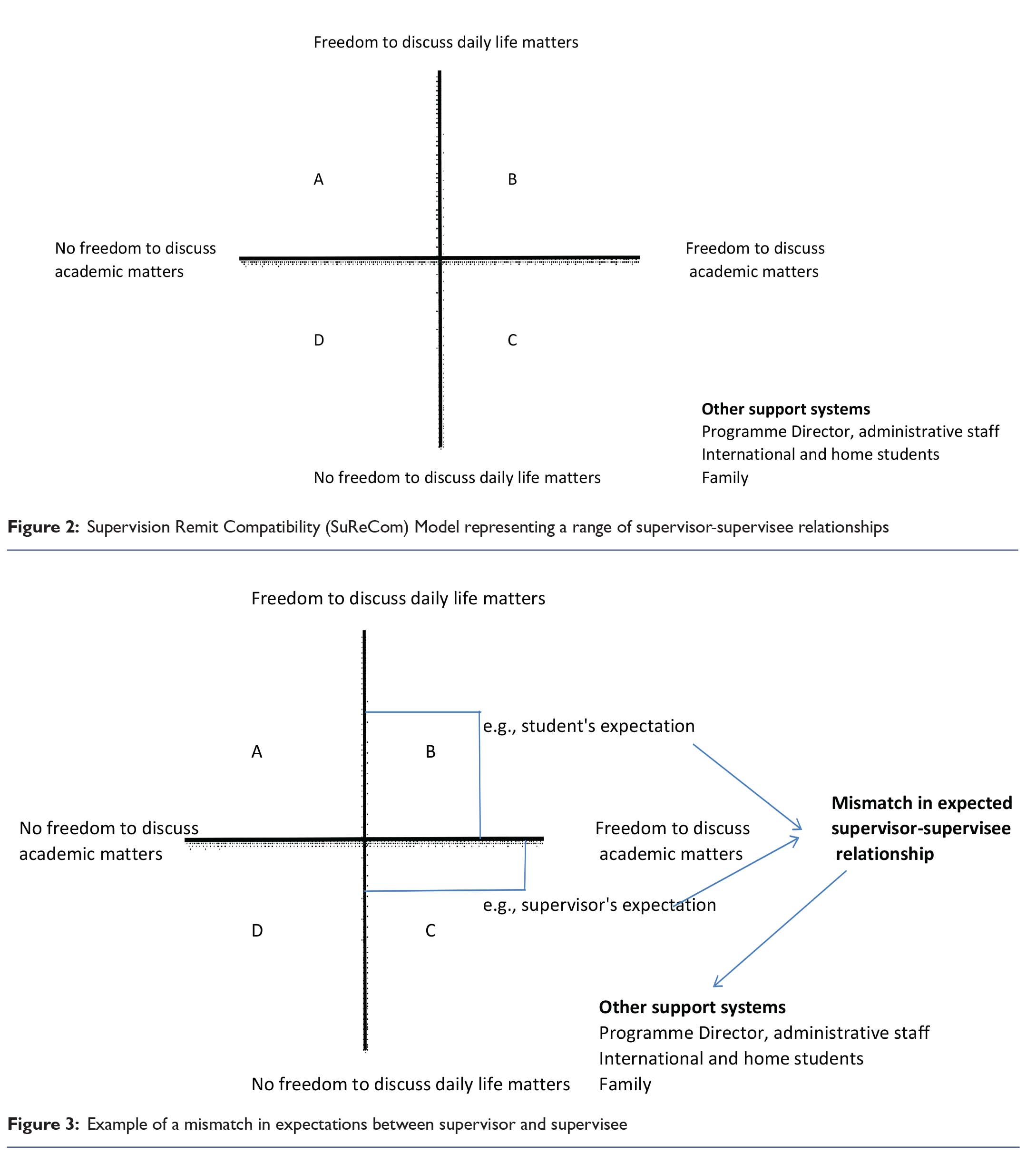

The SuReCom model is intended to visually represent and clarify the varying emphases that a doctoral supervisory relationship may embody (Figure 2). This model emphasises the need to make sure that the supervisors and supervisees are aware of their expectations of each other and have a clear discussion of the remit. It is proposed that SuReCom model can have a dual function, in that it is a useful depiction of the possibilities and relationships between the academic and personal facets of the experience of doctoral study, but is also intended to be used as a tool for students and supervisors to clarify the expectations and realities relating to their supervisory relationship. The latter is very important as a mismatch between expectations and realities has been seen to be a challenge for successful transition (Zhou, Todman, Topping, & Jindal-Snape, 2010).

The model allows for a great deal of flexibility as one can plot the degree to which one facet of supervision is relevant at any point on both axes, rather than merely stating that it is relevant in general. Quadrant A depicts a supervisory relationship which is focussed on daily life issues and does not involve academic discussion. This would appear to be one which is at odds with one of the core functions of doctoral supervision. Quadrant B allows for both academic and daily life issues to be explored and discussed, and would recognise the interplay and impact of daily life issues and academic study, and as such is desirable in terms of the key messages from the current study. Quadrant C portrays an academic focus and echoes the aforementioned construct of supervision being about knowledge transfer and creation (Grant & McKinley, 2011). Quadrant D depicts a negative supervisory relationship which neglects both the academic and the personal. It would seem unlikely that this would be an aspiration, but suggests that this model could be used as a tool to clarify the distance between aspirations and possible realities of the supervisory relationship.

The use of this model as a tool is potentially very powerful when considering the managing and clarifying of expectations around the supervisory relationship for international students (and indeed home students). It is intended to allow both parties to plot their expectations.

This may well highlight differences in intensity, or in some cases, polarised views about the role and purpose of the relationship (Figure 3). This will illustrate areas of commonality and difference, and should lay the foundations for a co-creationist approach to setting the boundaries of supervision. The tool would benefit from an approach which allows for debate, discussion and flexibility; whereby perhaps a compromise or new orientation is agreed. What is key here is that there is a degree of participation and clarity from the outset. The tool should not be viewed as working in isolation from other factors influencing the experience of international doctoral students. The reality for students is that they draw support and guidance from a range of sources (i.e. international students, administrative staff, programme directors, university counselling services and international students’ office, student union, etc.). The benefit of exploring and reflecting upon expectations and needs is that students and/or supervisors can identify unmet needs and seek support from alternative sources. It should be noted here that there may be organisational constraints impacting on supervisors at play here too. This would allow students to become pro-active rather than reactive in relation to seeking support.

Testing the SuReCom model with home doctoral students and supervisors

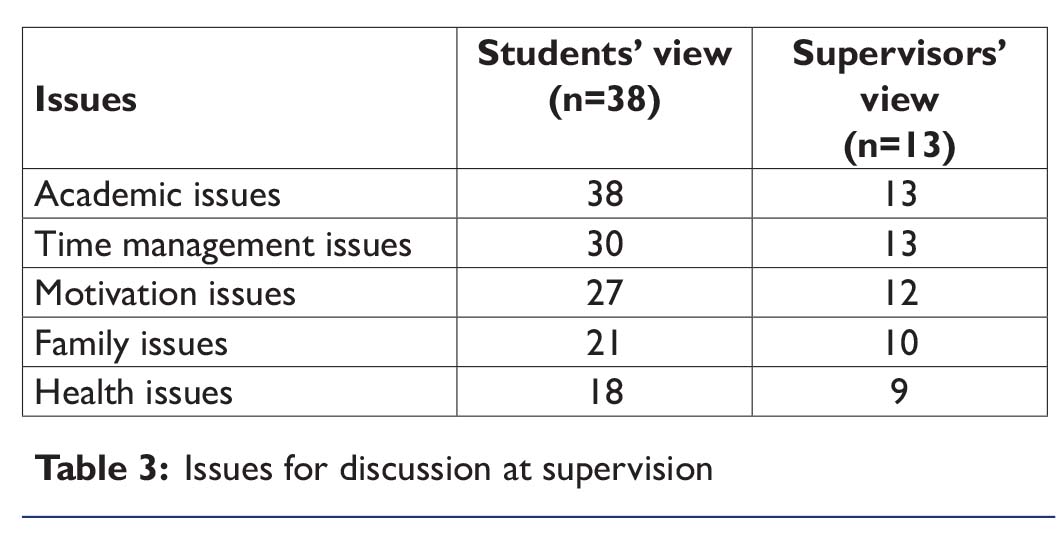

To understand whether this mismatch in expectations within the supervisory relationship was unique to international students and supervisors, research was conducted with doctoral home (domestic) students and their supervisors. Data were collected through an online questionnaire from 38 home students and 13 supervisors. The questionnaire included a mix of closed questions with space for brief comments as well as open questions where space was provided for their views in detail. This study was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee. When asked if they and their supervisors had discussed expectations about the role and remit of the supervisory relationship, 17 said ‘yes’, 11 ‘no’ and nine ‘not sure’. When supervisors were asked the same question, 11 out of 13 said they had discussed the role and remit with students, one said No and one chose not to answer. This suggests that there was a mismatch between the views of supervisors and supervisees, even when they were from the same organisation, nationality and had the same first language.

Table 3 shows what issues they said they were happy to discuss during supervision. It is interesting to note that when the issues were academic or time management related, there was a match between students’ and supervisors’ views; especially that all agreed that academic issues should be discussed. However, even with issues like motivation to study, a mismatch is apparent which is even greater in the context of family and health issues; suggesting that these are not seen to have an impact on academic life. As suggested earlier, educational and life issues are closely linked. Therefore, our models can facilitate clarity of these, as well as lead to a better match in role, remit and mutual expectations, as well as consideration of other support networks. These models are therefore significant, not only for international doctoral students, but also home students and their supervisors.

Conclusion

This paper uses theory and data to offer unique insights into the interrelationship between the educational and life transitions of international doctoral students. It also proposes two models that emphasise the importance of dialogue and transparency of expectations between supervisee and supervisors to ensure that good support networks are available to minimise any negative impact on the students’ academic progress and psychological well-being. Further, it provides a practical application of the SuReCom model to be used as the basis for a discussion of the role and remit to minimise the gaps in expectations and reality. The two models can be applied not only to international doctoral students but to others in diverse contexts.

It is important to highlight some limitations of the present study. The sample for the main study (and the one used to test SuReCom ideas) was small and from social science disciplines. Therefore, the findings are not necessarily representative of other doctoral students even in the same organisation. More in-depth interviews might have afforded the opportunities to collect richer data. Due to the sample size, it was not possible to conduct any statistical analysis that could have clearly demonstrated the relationship between academic and daily life transitions or mismatch between students’ and supervisors’ views.

Although the data on which these models are based are from a limited number of people, the models have been tested in different contexts. For example, ELT model has been presented to students starting university for their feedback and to see how it applied to their life. These students (and some staff) have verified the model. Similarly, the SuReCom model has been tested not only with the doctoral students, but also with social work supervisors and supervisees in the field who engage in formal supervision in the UK and their feedback has been positive. It is suggested that these models should be further tested with larger samples in diverse contexts. Both models are dynamic, and can be adapted and used over a long period of time.

Further, the theories behind the models are robust and they have been tested in practice. This study provides original data in the context of triple transitions in an area that is under-researched and under-theorised. It also provides two unique models that can be used effectively to minimise any negative impact of transitions and build on the positives, leading to better academic gain and emotional well-being of students. These are of significance not only in this particular context; they can be applied with doctoral students across the world and translated to other educational programmes and supervisor-supervisee relationships.