Phoebe Godfrey, Jessica Larkin-Wells and Julianne

Frechette

University of Connecticut, US

We cannot hope to create a sustainable culture with any but sustainable souls.

Derrick Jensen, Environmentalist / Author

As educators across diverse disciplines become increasingly aware of the need to address the challenges of anthropogenic climate change and thus promote its proposed antidote, the creation of ‘sustainable cultures’, the stark irony is that many of our students are anything but ‘sustainable souls’. In fact, according to the American Psychological Association, on an average college campus about 41.6 percent of our students are suffering from anxiety and 36.4 percent from depression (with many experiencing both symptoms) (College, 2013) and this does not take into account any residual anxiety or depression they may feel once confronted with the severity of our overlapping social and ecological crises (Pihkala, 2018). That classes such as ours which address these crises may exacerbate student’s pre-existing unstable mental health (see Doherty, & Clayton, 201; Fritze, Blashki,Burke & Wiseman, 2008), we are compelled to more actively cross what is increasingly being seen as a problematic divide between student mental health treatment outside of class and their experiences within class. In fact, as evidenced by a number of international university reports (Okanagan Charter, 2015; Texas Well-Being, 2018; Thorley, 2017), if we are to adequately address this near global epidemic that greatly impedes student learning and success (Eisenberg, Golberstein, & Hunt, 2009), then we must remediate not just the students themselves, as has been the practice, but our institutions, including what goes on in our classrooms. The Okanagan Charter (2015) proposes that higher-education institutions should, 1. Embed health into all aspects of campus culture, across the administration, operations and academic mandates. 2. Lead health promotion action and collaboration locally and globally. (p. 1). We, a professor (Phoebe) and two undergraduate students (one was a student mentor represented here by Jess, the other was one of 35 students represented here by Julianne), agree with these proposals but we also recognise that student mental health challenges intersect with and can be exasperated by social / personal oppressions such as racism, sexism, classism, LGBT-phobias and other forms of marginalisation that can compromise healthy identity formation (Hardy, et al., 2013). All of these social / personal oppressions are overtly and covertly manifested in our classrooms and therefore what we present here is a case study of our attempts at creatively engaging in individual and collective healing, as essential components of sustainability, through the practice of what we are referring to as an ‘intersectional compassionate pedagogy’ (ICP).

The recognition of intersectionality as a pedagogical approach that further develops the practice of feminist pedagogy has been gaining increasing popularity, as evidence by Kim Case’s edited volume Intersectional Pedagogy:Complicating Identity and Social Justice (2017; also see Trapper, 2013 ). Additionally, connections have slowly been made between feminist / intersectional pedagogy and environmentalism, (Gough & Whitehouse, 2003, 2017) including Godfrey’s own work (Godfrey, 2015) and more recently Maina-Okori, Koushik & Wilson, (2018) who propose that “we need to be open to acknowledging and dialoguing about our ‘pedagogical blind spots’...”, (p. 293) in particular, as they argue, those that are created by members of colonising cultures who continually fail to acknowledge and value Indigenous perspectives. To this we would add the need to also acknowledge indigenous pedagogy that has been introduced to us by the work of Donald Trent Jacobs / Four Arrows in Teaching Truly:A Curriculum to Indigenise. Mainstream Education (2013) and, which like the trend in compassionate pedagogy (Berlant, 2004; Gibbs, 2017), seeks to connect to and thereby educate the ‘whole’ person. For Jacobs, indigenous pedagogy “...weaves the empirical and the symbolic, nature and culture, self and community, power and love into a unified and unique vision of the world.” (p. 65). In this manner it is not only theoretically ‘intersectional’ in its recognition that “cognition and consciousness exist in an inseparable mind-body-spirit-nature unity that normal mainstream education breaks apart” (p. 66) but also in its pedagogical practice that “... sees rituals, ceremonies, rites of passage, places and family histories and connections as integral and vital to the learning process” (p. 65). Jacob’s recognition that ‘normal mainstream education breaks apart’ the intrinsically ‘inseparable mind-body-spirit-nature unity’ speaks directly to our recognition that we are in the midsts of not only a mental health epidemic but also overlapping social and ecological crises. By applying an intersectional analysis to these social phenomena we can recognise their inseparability as we further emphasise the need for alternative pedagogies such as ICP. ICP seeks to create classroom climates conducive to helping students repropergate their ‘mind-body-spirit-nature unity’ (similar to the emphasis on “head, hands & heart”, see Sipos, Battisti & Grimm, 2008) and thereby begin a very intimate, yet collective, healing journey. In fact, we sought to embody “kinship, and its expression in the compassionate relationship between …” [italics in original] (Ballatt & Campling, 2011, p.3) all within the class. According to Ballatt & Campling, (2011) “...communities that embody kinship to the extent that there is a common purpose, active recognition of interdependence and responsibility for each other, equality and warm positive interpersonal and group bonds, are very simply, healthier” (p. 26). This though did not mean we erased difficulties and differences in our identities and engagements but rather aimed to bring them as much as possible into the light of our collective learning and healing.

In this manner, our sociology class, Sustainable Societies (Spring 2018) at the University of Connecticut, sought to put ICP into practice in all aspects of the class and as a result Phoebe, along with her three mentors and 35 students, sought to challenge power inequalities in micro spaces, as in students’ socially constructed concepts of self /others and macro places, as in the social structure of the classroom, including the furniture, the use of the board and other traditional educational geometries of inequality. In essence, Phoebe’s goal for this class was to invite our class (including Phoebe) to become ‘sustainable souls’ individually / collectively and that this work should continue beyond the class through this collective, intersectional and compassionate writing project. To achieve this we have spent many hours sharing reflections, insights and new ideas and have chosen to divide the rest of the article into sections, allowing each of us to speak to what we did / experienced and then what we learned / gained as a result. Using autoethnography we are our own research, our own data and therefore we will conclude by collectively reflecting further on what our experiences mean to us now and how they and their implications in our lives continue to unfold as we recognise that there is no way to healing, but rather healing is the way.

For the past three spring semesters I have been teaching a sociology course that I developed titled Sustainable Societies. This past January I decided that although I was pleased with the course, including publishing with a former student on her / our experiences in our class (see Godfrey & Brown, 2017), I needed to try something new. I already based my classes on student centered pedagogy based on discussions and interactive activities, reflective journals and creative group projects but still felt I needed to do more to address student mental health challenges. My recognition of this need prompted me to make this issue the focus of my class. Yet in being only one person in a typical class of 35 students I realised I needed help, as in other undergraduate students who had taken a class with me before and who could model, hence be, ‘the change we wanted to see’. Therefore, I sent an email out to a diverse group of former students proposing that they do an Independent Study with me for three credits while being in essentially the role of my ‘teaching assistant’, but instead of focusing on grading as is the norm, they would focus on ‘creative community building’. In the past I have referred to this as creating an ‘earth community’ (Godfrey, 2015) but this time there would be much more emphasis on developing each student’s own creativity, and the community we would build would not just be between myself and my students but would have new bridging members. The student mentors in being both ‘undergraduates’ and ‘mentors’ would be much more capable of connecting not only with the other students but also with me. I ended up with three female student mentors all of whom were (are) passionate about social justice / environmentalism / personal growth / creativity - two of whom were white (and friends) and one of whom was African-American.

Our goal was to first build community between the four of us, recognising our power differences based on our social roles, education and race. Then I sought to help them develop their collective and individual leadership skills so that they would be able to engage in ‘creative community building’ with the students by maintaining the right balance between ‘structure and freedom’. My class met for 50 minutes three times a week Mondays / Wednesdays / Fridays and so the plan was to for me to engage in ICP while focusing on class readings Mondays and Wednesdays. On these days I ran discussions based on readings, as well as having students share their creative and intellectual work in both formal (presenting in front of the class their critical analyses / creative work) and informal ways (sharing in a talking circle and in doing brief group activities). Then for Fridays the mentors prepared additional activities to further engage in ICP. This schedule, including the courses’ emphasis on mental health and healing was stated on the first day and included in the syllabus to ensure that students knew what to expect. However, it was never implied that this emphasis would be anything more (or less) than allowing for student self-expression, engaging in creativity, and using ICP to build community through kinship.

One of the books we used is my co-edited volume Emergent Possibilities for Global Sustainably: Intersections of Race, Class and Gender (Godfrey & Torres, 2016), which placed intersectionality both as a theory and a practice in the forefront of our analyses of sustainability recognising that “...any actions taken in the name of sustainability…” must “...recognise the intersectional complexity of social and ecological justice” (p. 2; also see Ramsay, 2014). For example, we would read an essay from the book such as, ‘Womanism and Agroecology: an intersectional praxis seed keeping a an act of political warfare’ (Tyler & Frazer, 2016), then read poems from the book or look at images and then invite students to not only critically analyse the materials and make connections between them but to also write their own poems, do their own drawings. These poems and drawings were shared on Fridays with the mentors, while also engaging in other group building activities to further promote, practice and develop our ICP.

Examples, of some highly intersectional and astute poems that link issues of Western cultural bias towards STEM and against ‘nature’, as well as issues of racism, capitalism and our lack of emotional responses to them, come from Amber, who was “flattered” that we asked to use her poem for this article:

Sick environment.

No feelings, only science

Will solve the problem.

----

Trees? They are no good.

Solar cells over plain wood

Cut them down; I would

-----

My black blood is sold

Watering perishing mold

Nothing left but gold

-----

For me, these poems speak to her insights from the readings and show the emergence of her own critically empowered voice uniting ‘mind-body-spirit-nature’ in each potent verse.

Another example of a book we used is The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World, Paul H. Ray and Sherry Ruth Anderson (2001). This book helps students to see that progressive ideologies and practices such as women’s rights, racial justice, environmentalism and holistic health are becoming increasingly popular with those they term ‘cultural creatives’. To illustrate we did an activity where collectively we mapped out on the board how important such issues were to our grandparents, our parents, ourselves and our children (one student had children) and found that there has been a significant shift. This activity then led to Chris writing and later performing a poem called ‘Back in the Day’ in which he powerfully compares more traditional bigoted views of such social issues with his current views. The poems ends with the powerful lines,

All lives don’t matter if black lives don’t

Same sex couples can build up a home

Women want equal pay in addition to votes

That’s freedom to us, and it gives me some hope

In feeling ‘some hope’, the general consensus from the students was that linking texts with creative activities - poetry and drawing in particular was a very effective way to process the material and to enhance a sense of personal and collective voice that aids in the healing process.

Later on in the semester the mentors created three sub-groups that they individually led while focusing on an issue of collective choice that become part of a campus wide ‘environmental metanoia’. In so doing this they, and our students, added another layer of community to our ‘creative community building’, as in the larger campus community modelling the necessary ripple effect for any authentic personal and collective healing project.

In January 2018 I agreed, along with two other undergraduates, to take on this mentoring challenge with Phoebe. Each of us works for social and environmental justice in our own lives outside of the classroom, so Phoebe’s goal to model a ‘sustainable society’ in the classroom aligned with our values. Each of us, disappointed with standard educational practices in varying degrees, were still hopeful that the classroom could facilitate the change we sought in our day-to-day lives.

Our most fundamental goal was to model social sustainability as completely as we could – to practice what we preach. In a truly sustainable society, as theorised by Julian Agyeman in the term “just sustainabilities” (Agyeman, 2013), power is shared between people of different identities: we explored in particular the intersectional power dynamics entrenched in positionality of race, class, gender, age, and sexuality and the ways they also intersect with the natural world. We challenged these power relationships by prioritising healthy, hence honest, relationships within the classroom. These were our goals. I will continue with a logistical description of how we shaped the course.

The three of us met independently and with Phoebe each week throughout the semester in order to discuss previous classes and plan for the next Friday’s class. Though we explored many different activities, we maintained a consistent framework. We began each class with a one-minute group mediation in order to help students develop mindfulness, which is linked with increased mental health and pro-environmental behavior (Barbaro & Pickett, 2016; also see Howell, Dopko, Passmore, & Buro, 2011). Classes ended with ‘free-write’ and ‘appreciations’. Free-write was a time for students to quietly reflect on the class, themselves, or a prompt that we proposed; we collected the reflections and referred to them as we planned classes throughout the semester. During appreciations, the entire class would listen as a few students offered a brief compliment or appreciation of a peer.

Within this structure, our Friday classes took many forms. Recognising that personal and social intimacy is central to health and healing (see Okanagan Charter, 2015; Texas Well-Being, 2018; Thorley, 2017), we began by getting to know each other. Examples of conversation topics were siblings or parents, classes and other basic social engagement topics. We spent a portion of most classes in three consistent small discussion groups. Our class on privilege relied on structured listening circles, while a different Friday became an art workshop when we rolled out a long banner of paper and provided markers and paints. We sometimes played games in order to challenge our narrow understanding of pedagogy and focus the class’s attention. One favorite game was the mirror game, where students paired up, faced each other, and took turns leading motions (like waving or bowing) while the other “mirrored” them with their own body.

The final third of the semester was spent nearly exclusively in collaborative group work, preparing for the events each group planned for UConn’s metanoia on the environment. These campus community events were highly successful in that they stayed true to our ICP commitments while addressing impediments to sustainability such as toxic masculinity, our student mental health crises, oppressive pedagogy and social inequality. This concluded the class.

The first day of class I was immersed in an interactive activity that challenged the dissection of power structures that ruled my life. Topics flowed into another with comparisons to be made between them all. It never felt like I was confined to a strict framework. The overarching theme was to foster a stronger connection between ourselves as individuals and the environment. In particular, the class was pushed to focus on how our education system further prevented us from seeing the connection between the two. Through emphasis on the creative power within all of us, we completed journal entries and our own pieces of art that reflected our understanding. For the first time since childhood, I had the freedom to tune back into my creativity. Over time, I saw myself and peers begin to re-harness our natural need to self-express. The challenge was to shift our internal framework to one of connection to ourselves and eventually each other in order to create a sustainable society for all. One day we entered our classroom to find all of the tables pushed aside. Phoebe held a talking stick and we all took a seat within a circle. She invited us to discuss how we were feeling, to share something that was bothering us, and to find a way to connect this to the current class material. Most of us were still adjusting to this experiential way of learning that didn’t involve exams or lectures. Students began to share something that was weighing heavily on them. For some it was the pressure of their course load and others a recent experience that caused a reaction within them.

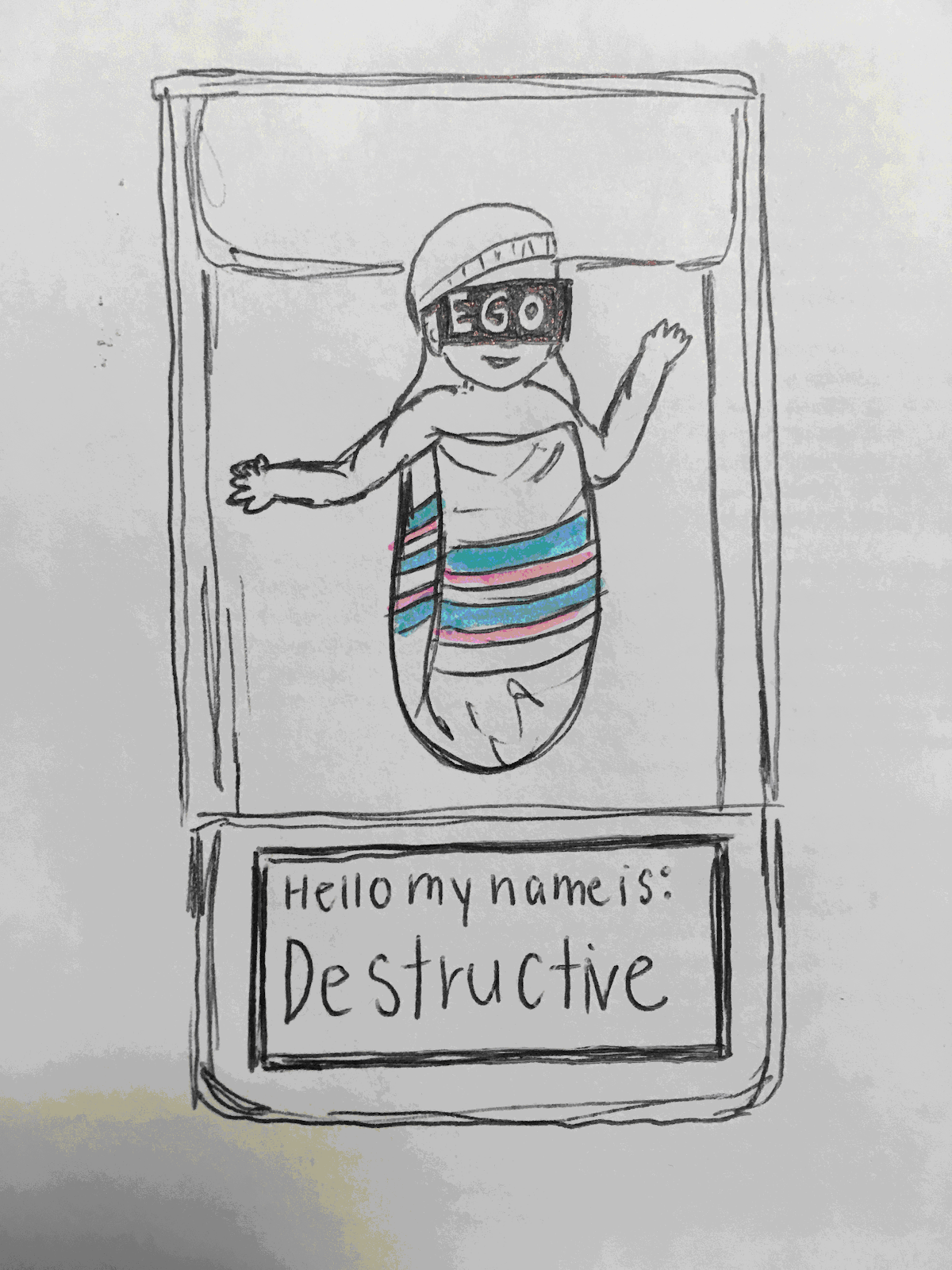

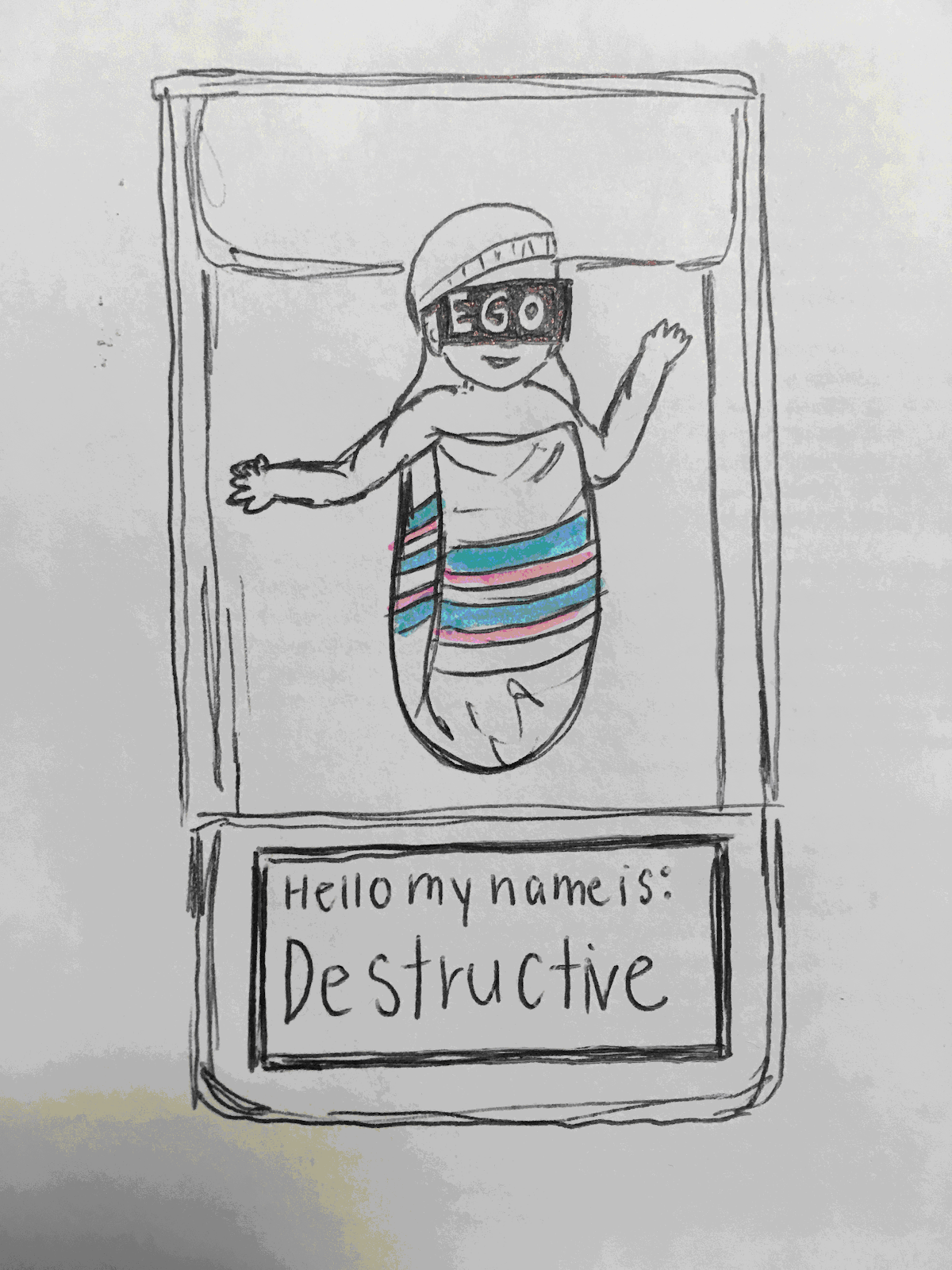

When I first signed up for Phoebe’s course, I was dealing with ongoing mental health issues. I soon found opportunities to reflect upon them in relation to many of our assigned readings and within my journal entries. For example, I began to understand that the perpetuation of my mental distress was caused by a disconnection from myself, from others and the environment. The confines of our social structures, especially those of the classroom, had convinced me I had to hide away my pain because it would contaminate others, preventing them from being productive members of society. I felt that I shouldn’t “burden” other people with my depression and eating disorder. After some time, I’d learned to blame the consuming nature and lack of motivation on myself. I have come to see that this is what most of us do. I cultivated an environment of alienation within a comfortable bubble that I never let others penetrate and through fear of appearing weak, I internalised the idea that I could not let others see my vulnerability. Before the experience of this course, I lacked the voice I needed to propel my identity to one of a ‘sustainable soul’. I felt like I was constantly trying to prove my intelligence to others, as if professors approval would validate my existence worthy. I learned to recognise that I was stuck in a limiting belief pattern based upon what the education system had lacked to provide for me (see my drawing, Figure 1). By breaking down my traditional learning process, I opened up a multitude of silenced pathways for my own intellectual, personal, and spiritual growth.

Figure 1: “Limiting belief patterns” by Julianne

I learned to find comfort in starting every class with meditation. One of the books we read was Intelligence the Creative Response to the Now by Osho (2014) in which he states, “Meditation is needed only to undo what the society has done. Meditation is is negative: it simply negates the damage, it destroys the illness. And once the illness has gone, your well being asserts itself on itself of its own accord” (p. 6). There was something very different about meditating in a room full of other people. When I closed my eyes and focused on my breath I found it easier to remain present. Through these practices, I re-conditioned my mentality of scarcity to one of abundant growth. I began to feel worthy enough to speak my authentic truth by allowing myself to feel vulnerable in our talking circle. We had created a circle of trust in which I could be vulnerable within.

The indigenous teachings and their emphasis that we adopted on “mind-body-spirit-nature unity” taught me that communities fostered the healing that I was seeking. Surrounded by the kinship we’d built, I discovered how cathartic it was for me to be open with others about my ongoing experiences of recovery without the fear of judgement. We learned to support each other and validate opinions while simultaneously challenging them further with the understanding that each of our perspectives was limited to what we had experienced based upon our individual privileges and / or oppressions. This had become that place that we all needed; to live by the example of what we desired right now.

None of this could have been possible without the willingness of Phoebe and our mentors to break down the hierarchy within the classroom. The line between teacher and student became fluid, resulting in a sense of mutual respect and an intimate closeness. I left this class hopeful for my own journey and hopeful for society. I have already seen a shift in my own perspective towards academic achievement since last semester. Every class is an opportunity to take control over my own learning and evolution. I feel myself no longer seeking the validation of others to propel my own motivation to learn. The opportunity to listen to my peers provided me with the chance to benefit from the wisdom of their mutual difficulties, cultivating the sense that we were a part of something larger than the setbacks that society and even our own minds had laid out for us. I now approach everything that I do with the freedom of mind that I can always transform my reality to one of another perspective, another earth. This speaks to the poem I wrote from which I have taken the following lines...

There is another earth

in another dimension

where we do not need to dull the pain

of a false reality

a lacking one

whose people look to outside sources

for the love

that is already within themselves

On this other earth

they do not seek material things

to give them power

to prove their worthiness

Because they already know

that they are worthy

of more than what they left behind.

As a result of my experiences in this class I now know that I too am “worthy of more than what I left behind”.

I was shocked to witness the significance of this class in many of the students’ lives. As Julianne said, the classroom became “our place for collective healing,” a place that fostered “mutual respect” and “intimate closeness.” In retrospect, it was not difficult for all of us to create this space.

In my own perspective, healing work requires challenging oppressive systems. Though activities like meditating and painting the mural are presented as therapeutic, they also strike at the core of the oppression of creativity and emotional expression in the university. By asking students to talk about their siblings and other personal information, we demonstrated that our priority was kinship and compassion. The silliest and most mundane activities of the semester were, in some ways, the most radical, and consequently the most healing. This is not a difficult model to reproduce, it simply requires a shift in priorities.

I believe the early time spent building community (Hooks, 2013) laid a foundation that helped students to cooperate and collaborate fairly when planning the larger community events later on. The same was true between the two mentors and I; as we spent time listening to each other about our personal lives, it became increasingly natural to collaborate efficiently while planning classes. No class was successful or complete without further building connection between and among students and mentors.

At the beginning of the semester, each of the three of us had an existing relationship with Phoebe, and two of us, Angie and I, were roommates and both white. We didn’t know Taylor, and her positionality as the only mentor of color set her up for a disempowered role within our group. We knew that structural racism would underlie our interactions, and the three of us decided to place exposing racism at the forefront of our work for the semester. We discussed how to embody this in the microcosm of our interactions, and also how to lead the class to this goal. We returned again and again to the topic.

As officially untrained teachers, one of our largest challenges was managing group discussion. Some students were more likely to dominate conversation, and though we hoped to model the sharing of power through well-balanced discussion, it was very difficult for us to enforce sharing airtime between peers. I still do not feel adept at asking others to stop talking, especially in complex and emotionally charged conversations about race and privilege. Practicing social sustainability in the microcosm required relentless attention to detail, “a creative response to the now” (Osho, 2004), as well as assertiveness from us, the mentors. Group discussion posed another challenge as we sought to balance personal reflection and scholarly discussion. Often, the conversations could swing one way or the other, and we were challenged, as Phoebe is as well, to draw upon both at the same time. These were some of the practical challenges we faced.

As mentors, what set us apart from our peers was an explicit allegiance to the group; it was our responsibility to be fully engaged with “the class” as a collective. I have found that engagement with the education of the collective fosters immense personal learning, and I have carried this forward into other classes where I have no formal authority. My time with Sustainable Societies reinvigorated my hope for change within the classroom, and I continue to practice this hope.

This is the second time I am writing this section, as the first time I used only my ‘academic voice’ and Jess and Julianne called me out, reminding me we had agreed to talk about emotions, about how we experienced what we did. I appreciate that they did this because our ‘academic voices’ are our safety voices, giving us space from engaging in what is amorphous and cannot be easily articulated or turned into a citation. Therefore, in speaking from my feelings I can say this class gave me joy, in that we were collectively creating our own evidence that not only is positive individual and collective change possible in some indefinite future, but it can be done and should be done as part of our commitment to higher education and ultimately to creating a more sustainable planet. In having worked with Jess and Julianne on this article and having read what they have written, as well as having witnessed their increased self-confidence, their increased emotional and intellectual maturity and their increased commitments to social justice, I feel what I and another student once described as ‘heartfelt hope’(Godfrey & Brown, 2017); an emotionally embodied experience of hope that links us directly to the communities of life that sustain us.

My learning from this class was that creating increased opportunities for student mentors is vital for achieving ‘sustainable souls’, in that such mentors can act as creative and healing ‘midwives’ for the students, for themselves and even for us as professors. My student mentors reinvigorated my commitment to using ICP, as well as Indigenous pedagogy and to working toward making mentors a more structured part of our university's self-claimed commitment to sustainability. Additionally, if we are serious about addressing the student mental health crisis on campuses, as well as addressing issues of sustainability we must put the proposals from the international university reports (Okanagan Charter, 2015; Texas Well-Being, 2018; Thorley, 2017) into practice, starting with personal and social connectedness that creates as Julianne said “a circle of trust”, which invites us “to be vulnerable within”.

In returning to the Okanagan Charter (2105) and to its Key Principles for Action the fifth one states that we must;

Promote research, innovation and evidence-informed action. Ensure that research and innovation contribute evidence to guide the formulation of health enhancing policies and practices,thereby strengthening health and sustainability in campus communities and wider society. Based on evidence, revise action over time (p. 11).

What we therefore find provocative is that most often when seeking such data we in the academy tend to ‘write about’ those who we seek to help, rather than creating contexts in which our ‘subjects’ (in this case students and / or those challenged by mental health), are invited to speak without shame to their own experiences and to have those experiences collectively heard and validated as part of their own, our collective, healing process. In other words, we see the need for more research that is done with and done by the very ones about whom we seek to help and to heal.

In reflecting upon our class, in writing with each other and in reading over each other’s’ work, we have recognised that this process been research and as research it provides evidence that what we did and how we did it has enhanced the health and healing of us as individuals and as a class last semester. Additionally, this flowering of health and healing has for us continued. We have created our own innovative evidence that by trusting in the healing powers of collective creativity, intimacy, mindfulness and kinship, along with on-going critical analyses of our social and environmental intersections, growth happens; ‘sustainable souls’ are born (Ericson et al., 2014). Obviously, we did not ‘heal’ all of the issues that distress us and our students and we certainly did not achieve a fully equal or oppression free space but nevertheless our experiences of the class and of continuing to work together on this article has shown us what it means to take ourselves, our mental health, our education and our commitments to social justice and sustainability seriously. This is the new imperative given where we currently find ourselves on the global social and ecological stages; may we all choose as Jacobs (2013) exhorts, “…a transition to a more beautiful, balanced way to living” (p. 13) by also creating more ‘beautiful and balanced ways’ of teaching, learning, researching and writing. We did and will continue and hopefully so will all from the class in ways yet unknown.

Dr. Phoebe Godfrey is an Associate Professor–in-Residence at UCONN. She is the co-editor of Systemic Crises of Global Climate Change: Intersections of Race, Class and Gender, and Emergent Possibilities for Global Sustainability: Intersections of Race, Class and Gender, London: Routledge. She attempts to put into practice that which she preaches.

Jessica Larkin-Wells is an undergraduate senior at UCONN. She lives at the student farm, attempting to practice environmental and social sustainability in her small community. She has been learning to bake bread as an expression of the intersection of all her interests.

Julianne Frechette is an undergraduate junior at UCONN. She is a sociology major and is interested in health / healing, social justice and sustainability. She is currently involved in creating a mindfulness center on campus.