Wendy Lowe, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Recently I read a twitter post by an Assistant Professor teaching social sciences to medical students who hoped that by “shar[ing] the shame it would help others put their own terrible comments in perspective. Teaching social science to health professional students is difficult” (Paradis, 2018). There were numerous responses to this ranging from commiserations, acknowledgement that teaching this subject is difficult due to the lack of context and real-life experiences of medical students who would much rather have an extra hour or two of Cancer, Microbiology or Pharmacology, who can’t see how this relates to their lives or – most importantly to them – the exam; turning to an acknowledgement of how tough some medical students can be with their feedback referencing a sense of entitlement on both the part of the lecturer and student, frustration with the sense that ‘one of the toughest problems medical students have with learning about the psychosocial dimension of human health and disease is the fact that the topics don’t lend themselves to simple yes/no answers. This makes some students angry and defensive’ (Paul, 2018); and a sense of the healthcare culture as being focused on ‘fixing’ when often there may not always be an answer.

On the positive side, there was plenty of encouragement to keep going with this thankless task since one day students may appreciate this – ‘have a lightbulb moment and suddenly get it and will remember your great teaching’ (David, 2018) – that often the perception was that the female lecturer was being chastised within a patriarchal culture for being direct and plain spoken, partly the focus on there being one right answer culturally in education and medicine was to blame., and that senior clinicians would get the importance of this subject immediately with no questions asked (Paradis, 2018). It was good to know that I wasn’t the only one who struggled with trying to deliver the social sciences in a way that was meaningful and relevant to medical students. I sensed that the responses were representative of a range of perspectives that centred on the suffering endured by lecturers, as well as students, when trying to integrate a social science subject into a biomedical course. Far from this being an empowering situation for all those concerned (Ellsworth, 1992), there is evidence of a great deal of suffering when trying to teach social determinants of health and infuse notions of social justice into seemingly privileged locations (Kendall et al, 2018; Bleakley, 2017; Kumagai, Jackson, & Razak, 2017). To me, this very awkward situation runs the risk of polarising even further the two fields of social science and biomedicine unless approached with compassion.

Compassion, as “a sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try and alleviate and prevent it” (Gilbert, 2017, p. 11) is both an approach with competencies, social mentalities and motivations, as well as an overall meta level of reflection, which is self-referential, in order to determine how to reflect on and learn to take action with a deeper focus into the nature of reality (Gilbert, 2017). Deep listening and attending to another person is also another hallmark of compassion (Epstein, 2017). The self-referential nature of the reflexive turn means that both self and other are included in the approach and action (White, 2017). This inclusion of both helps to counteract the oftentimes polarising nature of higher education (HE) and academic debate within and between the social sciences and biomedicine.

Identifying the polarising nature of HE and healthcare early on in my career as a physiotherapist and choosing to focus on it through the disciplines of education and sociology, then apply my understanding to medical education, is an expression of my own reflexivity and idiom; “that peculiarity of person(ality) that finds its own being through the particular selection and use of the object” (Bollas, 1989; no page number). The object in this case was teaching on the social determinants of health whilst the subjects were patients, medical students and myself (as a physiotherapist, researcher, sociologist, and medical educator). I see myself as searching for internal coherence (Elmore et al., 2014) of the object through reflexivity of both self and other that takes me beyond any one particular identity although this has been a journey of questioning my credibility and authority depending on which identity I have assumed. This has changed over time and now I prefer to see my professional identity as the conversation between disciplines – a complementarist approach (Moro, 2018; Cerea, 2018) – in order, through an inductive process of analysis of curricular phenomena, to develop a theoretical framework for the module Human Sciences Public Health (HSPH). I teach HSPH to second year MBBS medical students and first year Graduate Entry Program students. At this stage of their training, they have had limited exposure to patients and are immersed in learning about anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, pathology, cardiorespiratory and metabolic systems. The limited patient exposure comes from the Extending Patient Contact and Medicine in Society placements one day a week. However, students and their families have often been patients themselves, experienced ill-health, had their identities affected by these experiences through conversations with healthcare providers.

The conversational patterns of the above tweets reflect a compassion gap in both higher education and healthcare (Waddington, 2016) in relation to teaching social science in biomedicine:

But what are we doing about the compassion gap in universities that educate the people who go on to be the professionals who work in the NHS? The nurses, doctors, social workers and psychologists? If they don’t experience a compassionate learning environment in universities it’s no surprise that there is a compassion gap in practice! (Waddington, 2016, p. 1).

Creating conditions for compassion in higher education requires a commitment to intersectionality, inclusion of diversity and placing the student experience at the forefront of consideration (Waddington, 2017). At the same time, there needs to be an appreciation that compassion may not always be valued by people as it can be perceived as weakness (Spikins, 2017; White, 2017) in an organisation defined by competition and ruthlessness (Gibbs, 2017); qualities which present as obstructions to compassion (Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017; Worline & Dutton, 2017).

The reasons for including social sciences into a medical curriculum is to ensure doctors can deal with situations of uncertainty and complexity within the domain of professional values, behaviours and skills, as well as being able to apply social science principles, methods and knowledge to medical practice and integrate these into patient care within the domain of professional knowledge (GMC, 2018). However, while there is a willingness from professional bodies to acknowledge the importance of including social sciences, in practice there is a gap between intention and implementation in Medical Education which can manifest as a disconnect between learners and teachers. The disconnect can seem to be a void where a problem of student alienation, loss of meaningful human contact, with concomitant frustration and anonymity (Biesta, 2004), undermines any ideal of how students should graduate. Furthermore, while these ideals may drive teaching and learning within medical education, the actual state of student affairs is being missed whereby medical students suffer from a higher rate of anxiety and depression than other students (Erschens et al., 2016; Bugaj et al., 2016; Zisook et al., 2016; Schwenk, Davis, & Wimsatt, 2010). Social sciences could contribute to the required culture change (Coombes, 2018; Ward & Outram, 2015) if approached with a pedagogy of compassion that truly delves down deeply into the complexity and uncertainty that prevails within the relationship between the different disciplines.

The reasons why I have chosen to teach social sciences to medical students in a biomedical course is to be able to continue to work away at the edges of theory and practice in the hope of making a positive difference to patient outcomes. This is important because throughout my experience and studies, I realised that one could become positioned in either health or social sciences with very little, much needed, dialogue between the academic silos. Focusing on the edge between social influences and individual agency is both pragmatic in the health field through initiatives such as self-management of chronic conditions, as well as the site of theory in social sciences through ideas around how humans are formed and form their world. This edge is manifested continually in the meeting place (Foucault, 1973) between health professionals and patients. Here, incongruities first experienced as a physiotherapy student and later affirmed by health professionals’ responses to research on their training and the social determinants of health were apparent (Lowe, 2010). Compassion seems to be both a means and an end in addressing these incongruities as I shall explain below.

Incongruities such as providing advice to patients when clearly the tragedy of their lives – through poverty, events, colonialisation and enforced family separation, discrimination, migration, disability, chronic loneliness and isolation through illness and a suspicion of mainstream services, as well as the lack of access to a nurturing environment – meant that advice could often be interpreted as meaningless since it tended not to be tailored to their own situation (Clark et al., 2008). Worse, patients could even be judged for this lack of adherence or lack of taking responsibility for their own lives as evidenced by ‘victim blaming’ (Crawford, 1977). What are health professionals to do in the face of this complexity? Evidence supports management of a chronic illness through lifestyle changes and demonstrates a significant impact on symptom reduction (Health Foundation, 2016). Yet often these changes seem out of reach for many people and the evidence also seemed to support that some of this advice increased the inequity in health outcomes for people of differing socioeconomic status (White, Adams, & Heywood, 2009).

So I set out on a mission to try and understand this core dilemma of health professionals and patients. Through my studies I covered the ground of scientific quantitative research, education, psychology and sociology, and qualitative research; as well as working in acute care, educational settings and public health sites. I became impassioned with critical pedagogy as I developed training programmes within health. And yet was dismayed when my attempts at ‘empowerment’ seemed to go awry on an interpersonal level. I turned more towards my own self-management and explored trauma, embodiment and vulnerability.

Each area of study offered part of an understanding of this core dilemma of health professionals and each had its own limitations. While psychotherapeutic approaches shone in their compassion and humility as well as understanding the psychodynamic perspectives of transference and projection, there were also limits to understanding how the individual was constructed by social constructs / society through power and their own subjectivity. Also, did this approach mean that every health professional needed to become a pseudo-therapist? What was the demarcation between public and private domain of life and how much should we be asking for good citizenship? (Petersen & Lupton, 2000).

Social sciences analysed the impact of the social and acknowledged relations of power yet there were few explorations of embodied states – the body that lives, breathes, eats and sleeps – without a nihilistic undercurrent of believing that everything was constructed and therefore meaningless (Butler, 1993). In addition, most health professionals had not been exposed to the depth of social sciences so to use words like ‘discourse’ or ‘entanglement’ is to set up unnecessary confusion and distancing. The sociology of health, illness and medicine still seems to reside at the level of description – trends in the social determinants of health – without fully exploring why this understanding of the social determinants of health over the last 30-40 years is correlated with an increase in inequity in health.

Therefore, the question for my work, is ‘How can we teach social sciences to medical students in a way that is relevant and benefits both students and ultimately patients?’ My contention and suggestion is that compassion is both the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of the answer to this question in ways I will explain below.

The risk of education in any context involves setting out on a dialogic encounter with the self-other without knowing the absolute outcome in a predetermined way (Biesta, 2013). Whilst learning outcomes and objectives can be useful guideposts, the courage to teach and learn involves many more components than just these (Palmer, 2017). The trouble in Higher Education seems to be when the learning objectives are used as a way of seemingly enforcing equitable learning experiences across groups of students, reducing teaching to a tick box exercise for both students and teachers. This kind of reductive oppressive perspective on teaching and learning in Higher Education has resulted in learning objectives such as BeSST (2016) that do no justice to the complexity of how to incorporate these ‘facts’ into practice with students and patients; to make this understanding come alive in the confusion and overwhelm of knowledge and skills in medical education. The risk involves making what I see as ‘abstract’ facts (abstracted from patients’ lives) into concrete materialisation in and of patients’ bodies. To do this while entering the world is a huge task for medical students, when they rely on scaffolding of concrete information to help reduce the uncertainty and overwhelm of their beginning practice.

To me, what this requires is a wisdom of understanding the core dilemma of what it means to be human and have a body and a self, and to live in the face of terror and death (Becker, 2011; Gilbert, 2017). To do this we need a synthesis of pedagogies – from oppression (Freire, 2000), to hope (Freire, 2000), relational (Biesta, 2004) as well as critical feminist pedagogies (Lather, 1991). Each have their own nuanced analysis of the inherent dyad, the meeting place, in teaching and learning with suggestions on how to proceed. Duality is an established condition of teaching and learning in both health and education, and where compassion is necessary in order to keep alive the dialogic of the existential dilemma of having both a body and mind in the context of patriarchal transcendence model of control.

For this paper, I am focusing on the feedback I obtained during and after running the Human Sciences Public Health (HSPH) module. I had not received such negative feedback before as an educator in health so this was a challenge. The response rate was 44 students out of 275 MBBS Year 2, and 18 out of 46 GEP Year 1. The comments made in relation to the delivery were that it was confusing, unclear, the lecture and PBL objectives did not match the overall online objectives, the content was disorganised, that I had included too much information on sociology and the students wanted less – they were not sociologists and I had assumed too much prior knowledge. The pitch of the lectures was wrong, poorly structured and concepts were not well explained. There was too much inclusion of patient experience which the students did not find valuable and this made it harder for them to revise. They wanted short clear definitions, concrete information and less abstractions. A few students believed I was incompetent and should not be allowed to lecture without further supervision and training. That I had not cared about the preparation for the module given the slides I had produced.

On the positive side, some students felt like I was listening to their feedback and taking action to remedy the delivery of the module. Given the amount of effort I had put in to preparation for this module and the amount of reflection I undertook in order to try and get this module ‘right’ for students, the feedback was extremely disheartening and really shook my previously cherished notion of being a good educator. Although the response rates were low, I could not dismiss the comments as I felt that this was an opportunity to further analyse this teaching and learning situation with the hope of providing an improved approach. In addition, I felt that the students’ concerns with the module reflected my own.

My ongoing reflection on delivering this module to medical students has taken a number of different routes. Firstly, I carried out a thematic analysis of the BOS feedback where the main issue of concern and area for improvement was the structure of the module, as well as remembering the in-class feedback that I had taken on board and reflected on during the delivery of the module. Then I asked students to devise their own top three learning objectives that they would have liked to have achieved from the course, at the end of the course (Appendix 1). Then I carried out a curriculum development process to integrate these different perspectives. Over time and more exposure to and discussion with medical students, I also learned a great deal about the pressures they were facing so this led me to developing an informal list of reasons why compassion was necessary as a process for curriculum development. The process for this was as follows:

1. List all the reasons for compassion for medical students;

2. Use these reasons to give concrete examples of how social sciences may impact on their lives, introduce concepts and then relate to patients;

3. Cultivate internal coherence (Elmore et al, 2014) at a curricular level by thoroughly exploring assumptions underpinning the social determinants of health content.

The top three learning objectives (Appendix 1) centred on epidemiology, psychology and sociology. However, reading the written objectives, there seems to be an overarching theme of ‘how are individuals influenced by the social?’ That is, students want to know how the social influences the individual and vice versa. I have therefore structured the curriculum to reflect the emphasis of understanding the patient in relation to or embedded within the social context (Kristeva et al., 2017). The structure of this unit is vital as students also perceived the previously delivery as fragmented and piecemeal, which they found distressing.

I also attended a lecture that students rated as being good and noticed the stark contrast between myself and the preferred lecturer’s delivery. I had been wanting to engage the students and asked them questions, had moved around the lecture theatre – all of which are considered best practice in HE. But student feedback demonstrated they did not prefer this. They preferred a more soothing approach where information formed more of a narrative and where they formed a quiet audience (Sinclair, 1997). The words in use to me seemed to provide a structure, were often grounded in sensory words and linked to later clinical work. I interpreted this as a way of using narrative to provide a structure – I thought of Oliver Sack’s (1985) description of the need for a pattern design on the carpet, the warp and the woof, to hold everything together. There was a sense of the scientific narrative as providing something to rely on, to manage the challenge of being a doctor and that the threat of that being taken away by a critical sociologist was distressing.

So my understanding of the students increased over time. I tried to hold both the need for a narrative to hold everything together with the students whilst also understanding the value of critical pedagogy where I am trying to maintain a sustained engagement with structures of power (Ellsworth, 1992) in a way that promotes social justice, with its emphasis on deconstruction (Lather, 1991). To this end, I am developing a curriculum that centres around the narrative of the patient and health professional interaction or meeting place, which is reflected in the interaction between lecturer and student.

This analysis is of the teaching and learning process of a module that encompasses epidemiology, psychology and the social sciences through critical appraisal of research articles, the social determinants of health, health psychology theories of motivation, behaviour, adherence as well as public health and health promotion as applied to issues of ethnicity, race, gender, age and current social concerns such as knife crime and obesity stigma. The context of this module and analysis is in a medical school with second year medical students who have limited clinical exposure, and yet who are about to proceed into their third year where they will start clinical placements full-time. Therefore, there is a certain amount of anxiety present in the room about this transition into the clinical world (Becker, 1961).

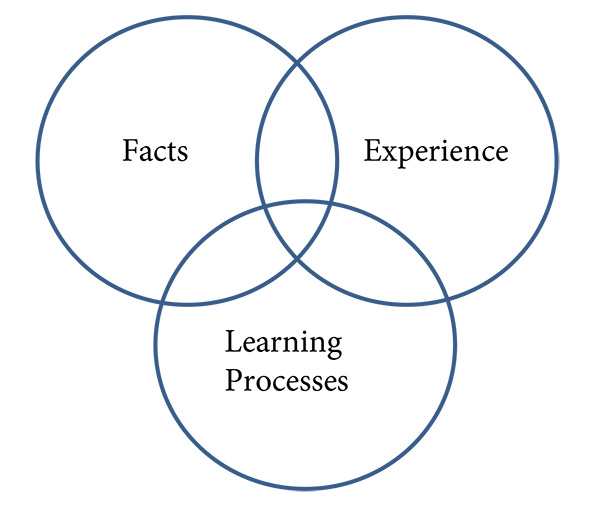

Further perceptions on medical students include the sense that they are thrown in the deep end in relation to NHS clinical work often with minimal hands on teaching and practice (‘See one, do one, teach one’ – Kotsis & Chung, 2013), there is a perception by some medical students that generally the institutions show a limited amount of personal care for them except through university student support systems; the complex environment of the NHS cannot be fully comprehended in the lecture theatre or on day placements; and in addition students are ranked against each other in a competitive environment that has implications for their future career with a perceived stigma about accessing formal mental health services so that they have trouble asking for help if they need it. This differs from my experience as a physiotherapy undergraduate and I am sure the same could be said for other professions allied to medicine including nursing, in that we had much more exposure to patients early on in our training and in fact were carrying a workload from the second year. This, along with the amount of practical lectures we had carrying out techniques under supervision, enhanced our capacity to perform once in the clinical situation. So while we may have had to cover most of the same core subjects – anatomy, physiology as well as the clinical specialities – we did so in smaller, more accessible groups, with less emphasis on competition. With these thoughts in mind, I will now explore a few points related to the facts, experience and learning processes embedded within the context of medical education (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Simplification of learning and teaching between teacher-student and health professional-patient

Doctors work with matters of life and death and have to assume responsibility for the treatment and well-being of patients. The amount they do this is somewhere on a continuum depending on the patient, the clinical speciality in which they work, the team they work with as well as with the patient’s family. Ultimately, in matters of accountability, doctors tend to take the full load with all that involves including day-to-day anxiety and uncertainty about patient outcomes. Therefore, the knowledge they rely on is of high stakes as reinforced by the evidence-based movement and the competitive nature of the medical program, funding for research and accolades for good behaviour. Therefore, facts become very important in negotiating matters of life and death.

The amount of factual medical knowledge required has a direct relationship with the level of trauma and risk of death. That is, the pressure of knowledge and technique acquisition and legitimation increases with the need to get it ‘right’ in situations of high cognitive, physical and emotional loading. This is as it should be. No-one would argue that medical knowledge is not important. There is also more that could be explored here in terms of health professionals’ relationships with these biological, chemical, physical facts, the situations in which these facts need to be deployed, and the concomitant fall into reductionism and fragmentation of the body and identity (Lempp, 2009). To consider also that these facts act as necessary limits in order to make healthcare possible.

Making healthcare possible has included clinical detachment and the need for objectivity as ethical and moral imperatives. In addition, social influences such as the nature of training, have encouraged this setting apart of doctors to enable them to carry out work that is beyond capacity for many other people. The sheer amount of knowledge required means that medical students spend a longer time studying as well as doing so more intensively than perhaps other undergraduate students. In order to be able to manage the amount of overwhelm inherent in any institution such as the NHS, society has imposed limits and the doctors are the professionals who perhaps enact these epistemological limits more than anyone else within the health system. Whilst at the same time, they are revered culturally for all that they do in the name of healthcare, certainly in the past. This psychological paradox and tension between self and other in the meeting place, with epistemic limits (Fricker, 2009), underpins any relationship with facts and forms part of the experience of healthcare.

By this, I mean the experience alongside the ‘what’ or content of learning and practice, which is often formative of the hidden curriculum and perhaps responsible for the compassion gap. I mean ‘how’ the embodied student (patient) experiences the encounter in education (health); that is, the inclusion of the cognisant subject for consideration – what impact is the curriculum having on the student? Since the price of objectivity within a positivist paradigm is the exclusion of the cognisant subject in order to maintain this objectivity, inclusion of experience is a challenging notion for mainstream health professional training. How to do this given the points made above? This is the challenge facing healthcare and clinical research currently as patient involvement gains momentum. What is certain is that an either/or binary is not helpful where facts or experience have to fight for survival, pitted against each other. Going beyond this seems necessary and only able to proceed by thinking about how some of the assumptions we are operating under could be challenged.

Challenging the assumptions requires moving beyond both the biomedical and sociological reductionism (simplistic reductions of suffering and health injustice to cultural relativism or biology – Kristeva et al., 2017). This in turn requires moving beyond the causal problematic; that a fuller understanding of every human phenomena requires a constant movement from and between one level of explanation to another, between cultural and psychological explanations (Cerea, 2018). This ‘double discourse’ epistemology founded by Devereux rests on an assumption of a ‘psychic unity of mankind’ that accounts for the ‘anxiety’ arising in the encounter with the Other:

When the feeling of anguishing commonality appears, which, instead of being considered as an impediment, becomes a tool of knowledge of the human being, the only possible scientific knowledge. For Devereux, this ‘anxiety’ is the specific object of the behavioural sciences and their most important cognitive moment (Cerea, 2018; p. 306).

Using the complementarity of disciplines to move beyond culture or psychology means moving beyond individualising of responsibility for social determinants of health. Creating an awareness or social action on the effect of cultural systems of values on health outcomes (Sharma et al., 2018; Kendall et al., 2018) only reinforces the ontological divide that caused the problem in the first place with the concomitant need for translation between epistemic and ontological domains (Kristeva et al., 2018; Cerea, 2018). Decentering the causal problematic means developing a curriculum based on principles of complementarity and dual awareness of both cultural and psychological functioning as an act of compassion.

Medical practice is changing as the gap between the advantaged and disadvantaged continues to increase. People who are deprived have the worst health outcomes, the most co-morbidities, the longer period of ill-health before they die (20 years compared with 10 years for the least deprived part of the population), and who also suffer excess deaths over and beyond the standardised mortality rate once socioeconomic status has been adjusted for (O’Mahony, 2016; Walsh et al., 2016). These summary epidemiological statistics are the facts covering the actual people who are most often involved in trauma, chronic illness and therefore admitted to hospital more often. Doctors will be working more with more seriously ill people. Feeling the anguish of this situation, particularly in relation to the recent epidemic of knife crime in east London, for example, means that a more nuanced understanding of the inter-relatedness of poverty, marginalisation, identity, trauma, vulnerability and crime is necessary at all levels of intervention. Adopting a trauma informed healthcare service (Reeves, 2015; CDC, 2018) that attends to this experience for both patients and healthcare professionals not only makes sense; it is an act of compassion too. And this is also where the relevance of the social sciences becomes more prescient. For example, understanding the relationship between ill-health, trauma, stigma, poverty and marginalisation may make health professionals better understand the revolving door of GP clinics (Lowe et al., 2014).

The sociological imagination (Wright Mills, 2000) enables a stepping back to see the bigger picture. Public health frameworks aiming to expose the social determinants of health by linking upstream inequalities with downstream interventions and health outcomes were the first to use the analogy (National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2014). The initial idea was that public health and health promotion workers were the people on the banks of the stream extending a helping hand. However, given that inequities have only increased over the last 30-40 years (Commission for Social Determinants of Health [CSDH], 2008), along with physician burnout, stress and pressure within the NHS (Miller, Mcgowan, & Quillen, 2000; Hawton, Clements, Sakarovitch, Simkin, & Deeks, 2001) I would suggest that both the public and physicians are now in the stream swirling around in their own Self / Other whirlpools as they are swept further and further downstream out to an existential sea.

As an example, patient self-management of long term conditions relies on a number of psychological theories as considered within the HSPH module. However, the cognitively based interventions do not always match the experience of patients and their families. At times like these, psychological interventions still operate as normative judgements about desirable change from a privileged utopian notion of transcendence about health and long term conditions. These repetitious mismatched activities, or spinning hamster wheels (Lowe et al, 2014), as one doctor called his practice when dealing with recurring patients with chronic illnesses, are the whirlpools in the stream. Here, the epistemological objectivist paradigm meets the ontological phenomenology of the patients’ existentialist paradigm.

These whirlpools in the stream of body and mind; patient and doctor; student and teacher; may be what we need to become aware of in order to make any real change of a meaningful kind. If we can consciously integrate the body mind split (Belkin, 2001) by teaching and learning facts and skills, alongside the experience and the process of learning, then perhaps we can be more aware as we navigate along the stream. However, blaming either the doctors for their objectivism or the patients for their lack of adherence to this objectivism is ultimately not helpful. Likewise, as teachers blaming medical students and then doctors for an inherent existential dilemma (having both a mind and a body; Becker, 1973) which we all experience – both health professionals and social scientists as well as patients – only amplifies the mismatch of the situation. Including experience through different perspectives enables medicine to gain the ability to understand and respond to needs of individual patients, social networks and whole communities by including both the observed and observer points of view (Kottke, 2011).

As mentioned earlier, teaching can be seen as an understanding of power and equality which can function as assumptions that require continual awareness of our actions in the here and now (Biesta 2013), as much as possible (Brookfield, 1995). Understanding power and equality means following lines of student enquiry and feedback – when they state that the course is fragmented – they are right both at a practical and epistemological level. So how do we change that meaningfully? This is a challenging question given the assumption that any action in this regard from within a fragmented field tends to produce similarly fragmented solutions (Bohm, 2002). In order to address the disconnect, I have been turning the material towards the student and encouraging their reflexivity on how they may be affected by the concepts. For example, in one lecture, I asked the students to state which social class they identified with (anonymously through technology – mentimeter.com). There was a U-shaped curve with most students identifying with social class I (43%) and II (28%), less in the middle (III – 11%, IV – 5%), and a significant minority identifying with social class V (14%). Since compassion varies by social class (Piff & Moskowitz, 2017), this may have implications for the level of interest of students in hearing about and engaging with the effect of social factors on health. These proportions may change as Widening Participation increases (Martin et al., 2018; Cleland, Nicholson, Kelly, & Moffat, 2015).

The continual development of a module that takes into account learning processes, psychology and sociology as well as biomedicine means that each lecture must be reviewed for its relevance and questions asked such as these developed with a colleague:

1. What does this mean for me?

2. Where does this come into practice?

3. How does this affect my practice?

4. Why is it important?

5. Who is affected by it the most?

6. When will I experience this? (Location, setting, time.......)

7. Key take away message

Furthermore, practical steps for curriculum development must include the acknowledgement of principles such as (i) The universality of psychological functioning, biomedicine and social justice; (ii) Cultural coding or conditioning that affects all humans; (iii) A complementarist approach; (iii) Understanding of confirmation bias; (iv) Othering and the relationship with responsibility, choice and control; (v) Understanding of the role of Big Pharma, government policies, advertising; addiction processes such as the opioid epidemic, for example; (Gotzsche, 2013; Mars, 2010) (vi) ongoing hostile environments which encourage learned helplessness for many people; and (vii) understanding strategic essentialism (Whitmarch, & Jones, 2010) as a starting point to continue to unravel the problem of social determinants of health curricula. This means that the relationship between psyche and culture for all involved will be examined instead of polarising what exactly is seen as cause and effect between individuals and the social (Cerea, 2018). This means whilst understanding that we are all complicit in contributing to the social inequities (Sharma et al., 2018), we do not become paralysed with a level of responsibility that is overwhelming. At a recent team meeting on HSPH planning, these principles were discussed, understood and accepted by those present which seemed a real achievement in itself.

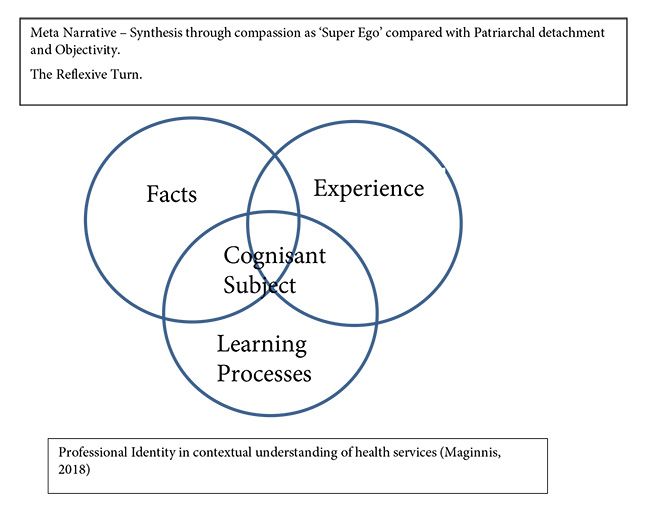

Figure 2: Teaching and learning through/with compassion

The existential dilemma of being both a self and a body in the context of patriarchal transcendence strategies within Medical Education can only be met with compassion in order not to reinforce the split. Compassion may just be the tool for a conversation between polarised viewpoints which in the end are about trying to achieve better outcomes for patients and health professionals. Our own lack of clarity about social determinants (MacIntyre, & Petticrew, 2000) and how to intervene makes this a challenging task to teach medical students on any meaningful level, when they are focused on techniques and saving lives. The core construct in a compassionate pedagogy must be the Othering and distancing we do through means of external markers such as social determinants of health – gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion etc. We are not trying to make sociologists out of medical students. However, we can use the social sciences to give concrete examples of how social markers may impact on their lives, and then relate these to patients. By doing so, we may be able to address the ‘crisis of professionalism’ (Hafferty, & Castellini, 2009). Only by including the medical student in a compassionate dialogic conversation on the social influences on health and well-being, on both themselves and patients, will medical educators be able to begin to address issues of identity, power and location (Bleakley, 2011). This may well mean turning the sociological imagination on to the way social sciences are taught within medical education itself to prevent further polarising, Othering, and to thereby enhance a complementarist approach between disciplines.

HSPH – Student centred learning objectives

Please write three learning objectives that you would like to have achieved from this course (e.g. what would you be able to know or do as a result of this course)

Suggested learning objectives

|

Collated Learning Objectives |

Frequency N = 20 students; 62 suggestions (%) |

|

Name & describe different methods of studying diseases & appropriate statistical test used by medical staff – epidemiology. To know enough statistics to critically appraise a paper. Clinical trials and ethics. |

16 (26%) |

|

Health belief models – adherence, beliefs, behaviours, outcomes – link to social determinants. To understand what influences patients and their beliefs about treatment and adherence. |

13 (21%) |

|

Social determinants of health – specifically related to Tower Hamlets. Understand how socioeconomic & geographical factors affect access to and uptake of healthcare. How do socioeconomic factors affect an individual and their choices? To understand how cultural beliefs affect an individual’s perception of healthcare. Which factors contribute to childhood obesity? How does an ageing population effect the NHS? |

13 (21%) |

|

Operational issues – concepts applied to real case studies e.g. Ebola. Application of theory to practice – how can it be related to the NHS & our experiences? Name some techniques Ops use to help people self-manage. Health risk. The importance of patient education and health literacy. Life course perspective – how early childhood can affect later life e.g. child abuse/PTSD etc |

6 (10%) |

|

Public health – the history of public health. How diseases can be managed from a community point of view. Understand, compare & contrast the health promotion models with regards to chronic diseases. |

5 (8%) |

|

Patient centred care – what does it require & factors affect good execution – sociological theories & apply to patient centred care. To appreciate the complex psychological background behind the agenda of the patient, doctor and other staff associated with medical model. |

3 (5%) |

|

NHS & Other healthcare systems worldwide. Global health trends. Examples of countries with different practice e.g. Norway/Iceland vs Africa. Understand definitions which will appear commonly in papers and day to day life as a doctor/patient. |

3 (5%) |

|

To discriminate between scientific and social constructs of knowledge making in relation to career of a medic. Understand different knowledge frameworks with examples. Understand key terms – objectivism vs subjectivism. |

3 (5%) |

Wendy Lowe

is a Senior Lecturer in Medical Sociology & Medical Education and Module

Lead for the Human Science Public Health module in Years 2 and 3 of the MBBS

and GEP (Years 1 and 2) at Barts and The London School of Medicine and

Dentistry. Her PhD explored how health professionals are educated and some of

the consequences of that.

Email: w.lowe@qmul.ac.uk Twitter: @medsocmeded