Ellen Spaeth, University of Glasgow, UK

A body of literature has explored how we, as facilitators of learning in Higher Education, can improve our practice in the realm of feedback (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Winstone, Nash, Parker, & Rowntree, 2016a; Winstone, Nash, Rowntree, & Parker, 2016b).Yet National Student Survey (NSS) scores remain low in the domain of assessment and feedback (Office for Students, 2018). I argue that one factor perpetuating these low scores is a lack of attention paid to the importance of emotional investment on the part of staff when giving feedback, how this conflicts with workload and quality enhancement requirements, and the impact of this on students’ ability to engage with this feedback.

I propose that underneath this lie the assumptions that 1) positive emotions can improve student learning; 2) feedback can promote positive emotions; and 3) giving feedback that can promote positive emotions requires emotional work on the part of the educator, and these will now be discussed in turn.

The first assumption posits that experiencing positive emotions can improve student learning. This is a concept that has been studied, in particular, by Pekrun and colleagues.

Pekrun’s (2006) theoretical paper explores an integrative framework in which emotions related to one’s achievement are linked to one’s appraisal of control and values, within the context of Higher Education. For example, Pekrun proposes that where the student feels they are less likely to fail (i.e. they are in control); and when failure is less likely to harm them (i.e. they do not have negative values about the academic context), they will be less likely to experience negative emotion.

To explore this control-value theory further, Pekrun et al. (2011) conducted a study exploring an Achievement Emotions Questionnaire that they had developed. The authors argued that experiencing positive emotions would promote intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, aid self-regulation, and help students implement flexible learning strategies, and that negative emotions, such as boredom, would reduce motivation and processing of learning materials. Students (n = 389) completed the questionnaire, and results were analysed using confirmatory factor analysis. Results supported the authors’ hypotheses, finding that positive emotions such as enjoyment, hope, and pride were positively correlated with intrinsic motivation (enjoyment: r = 0.45; hope: r = 0.41; pride: r = 0.35), learning strategies such as elaboration (enjoyment: r = 0.40; hope: r = 0.44; pride: r = 0.42), and self-regulation of learning (enjoyment: r = 0.26; hope: r = 0.45; pride: r = 0.43), as well as academic performance (enjoyment: r = 0.15 ; hope: r =0.19 ; pride: r = 0.15), in a class setting. Learning-related and test-related settings showed similar trends (p for all< 0.05).

These results provide a provisional basis for the promotion of positive emotions in the context of student learning.

Having discussed the capacity of positive emotions to promote enhanced student learning, the second assumption, that feedback can trigger positive emotions, will now be explored.

Firstly, in their seminal paper on principles to abide by when giving feedback on formative work, Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) argue that good feedback practice “encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem” (p. 205). They propose that this will help students to become self-regulated, therefore more effective, learners.

Following on from this, Rowe, Fitness, and Wood (2014) carried out empirical research exploring the role of both positive and negative emotions in feedback in Higher Education. They conducted interviews with both students (n = 21) and lecturers (n = 15). Qualitative analysis highlighted that negative emotions could result in students ignoring future feedback. Conversely positive emotions, such as happiness and pride, were felt when interest was shown in student work; and happiness and comfort were felt in response to personalised feedback. The authors concluded feedback could indeed promote positive emotions, and that it was important to incorporate positivity into the feedback process.

The previous two sections provide preliminary support for the argument that evoking positive emotions through feedback can lead to improved student learning, and that we, as educators, should aim to promote this within our feedback practice.

I argue that giving feedback that promotes these positive affective responses involves emotional labour, which can be defined as “the effort which is required to display that which are perceived to be expected emotions” (Ogbonna & Harris, 2004, p. 1189). In this case, the emotional labour involves amplifying the display of positivity.

Meanwhile, because of workload intensification, we are being asked to focus on being consistent and able to produce large amounts of feedback in a small space of time (or use unpaid time, in some circumstances). In their study interviewing lecturers about the consequences of work intensification on emotional labour, Ogbonna and Harris (2004) argue that lecturers are emotionally detaching from students due to high numbers, therefore using emotional suppression as a defensive coping mechanism.

In addition, workload models typically allocate less time than it takes in reality (Darabi, Macaskill, & Reidy, 2017) to give considered feedback that is fair, consistent, and meets the relevant benchmarks as well as being emotionally nurturing for the student, further increasing the pressure on the educator.

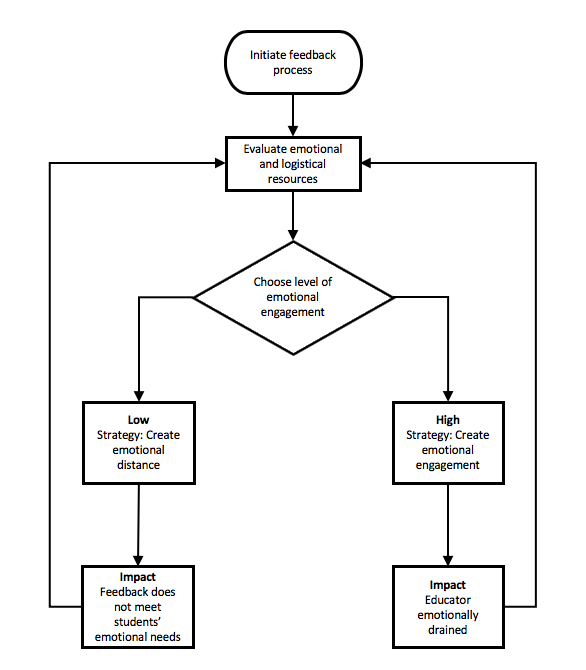

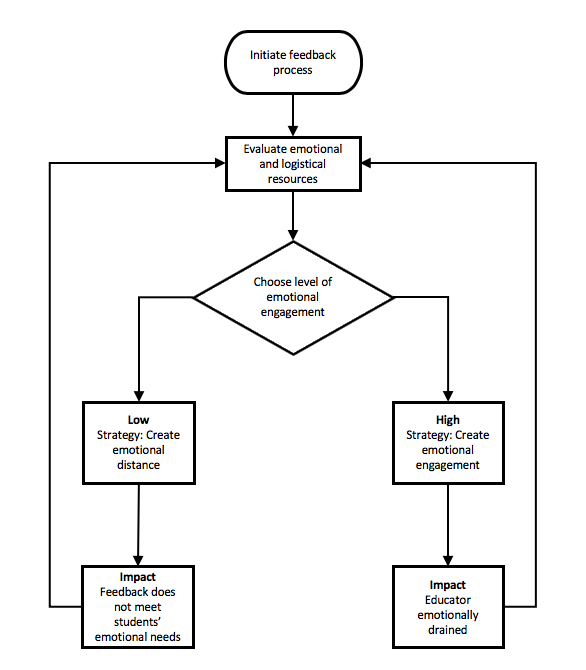

This results in two potential, competing, outcomes involving repressing or arousing emotion, which Ogbonna and Harris (2004) identify as techniques frequently reported by participants (UK lecturers). In the first outcome, emotion is amplified to maximise positive, emotionally-nurturing feedback; and in the second, it is suppressed in order to be efficient and cope with high volumes of students.

Figure 1 describes in more detail how educators might: 1) engage emotionally, which involves emotional labour, and may conflict with other pressures, resulting in potential burn-out for educators; or 2) distance themselves emotionally, potentially resulting in feedback that does not engage with the students’ emotional needs.

Figure 1: Model of emotional engagement for giving feedback

How can we address this issue? An initial suggestion would be to engage educators in discussion about emotional labour, to raise awareness and surface their feelings, opinions, and coping strategies. Another potential step would be to create guidelines on what kind of feedback can promote positivity. This might enable educators to evoke positive emotions in the student without as much emotional labour on their part. Further work is required to explore how we can support educators to remain compassionate when giving feedback without burning out due to stress or failing to provide timely feedback. In a time where “scaling-up” is considered a priority, it is vital that we find answers.

Ellen Spaeth is an Academic and Digital Development Adviser at the University of Glasgow. Ellen has particular interests in the pedagogically-led use of technology and the emotional impact of learning, teaching, and assessment practices.