Cheng Tak-lai, Lancaster University

Instead of occupying a sole position in a pre-determined role as educators, kindergarten teachers occupy multi-faceted positions as administrators, communicators, advocates and leaders who face ongoing daily challenges (Ohi, 2014). In response to this complexity, supervised fieldwork placement is particularly important to institutional kindergarten teacher training because this authentic learning experience helps shape students’ competence and prepares them to enter the childcare workforce (Thorpe, Millear, & Petriwskyj, 2012). As one of the largest tertiary sectors offering early childhood programmes in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Institute of Vocational Education (IVE) is no exception. In this circumstance, this present paper aims to review this higher diploma program’s fieldwork placement in the academic year 2016/17 in response to the programme stakeholders’ concern – how do the supervisions develop students’ professional identity when entering the childcare workforce? Before delving into this primary question, the paper first describes the program’s background and the needs of newly formed valued-branch evaluative practices. After demonstrating how the responsive evaluation approach can utilise this new form of work, the paper employs the practical tool RUFDATA to frame the key evaluative aspects, namely, reason, use, focus, data, audience, timing and agency. To conclude, this qualitative work reports the evaluation results and implications, drawing on case interviews with students who have just completed the fieldwork placement in spring 2017.

In Hong Kong, the field of early childhood education has suffered from a lack of kindergarten professional training since the 1980s; the government and society have even attacked kindergarten teachers’ contributions to children’s learning because of this predicament (Chan & Chan, 2003). In this regard, the government’s 1981 White Paper began calling for kindergarten teachers to receive the 120-hour part-time basic training of Qualified Assistant Kindergarten Teacher (QAKT). However, this target was merely rhetorical because the government was still wondering whether kindergarten education was indeed essential, and its financial commitment to supporting kindergarten education remained limited. Until the early 1990s, the government had increased its support for early childhood education and provided HK$163 million in funding for kindergarten teacher training. As a result, 38.4 per cent of kindergarten teachers had received QKT training by 1998, rising to 86.5 per cent by 2004. However, these efforts still could not change the perception that kindergarten teachers are undertrained. This tension was not relieved until the blueprint ‘Proposals for Education Reform’ was published in 2000 (Pearson & Rao, 2006), which served as a real turning point concerning the quality of early childhood education because one of its missions was to enhance Hong Kong early childhood educators’ professional competence (Education Commission, 2000). In the following years, the Education Bureau has made continuous efforts to enhance kindergarten teachers' academic qualifications (Wong & Rao, 2015). In the 2001/2002 academic year, the minimum academic entry qualification requirement for new kindergarten teachers was raised to five passes in the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examination (HKCEE), including in Chinese and English subjects, and all serving kindergarten teachers were also required to be certified as a Qualified Kindergarten Teacher (QKT) in the following year (Education Commission, 2000). Starting from the 2007/2008 academic year, kindergarten teachers must fulfil a minimum of the prescribed academic requirements to be issued a permit to teach, in equivalence of the Certificate in Early Childhood Education requirement under the Education Ordinance, with a common 360-hour supervised in-field practicum (Fung, 2014).

The Institute of Vocational Education (IVE) is one of Hong Kong’s authorised tertiary institutions offering an Education Bureau (EDB) recognised early-childhood education programme, whose graduates can register as QKT’s. The 2-year full-time higher-diploma programme in early childhood education is government funded and is offered by the Department of Childcare, Elderly and Community Services. With the department’s 35-year history, it is, at present, nearly the largest institute offering a kindergarten teacher training programme in Hong Kong, with over 1200 graduates in the past three years, which represents approximately 10 per cent of the total employed childcare workers and kindergarten teachers in Hong Kong in 2016-17 (Education Bureau, 2017). However, unlike other tertiary colleges, as a member of the Vocational Training Council (VTC), which is the largest vocational and professional education and training provider in Hong Kong, its teacher training programme is vocational-oriented, has a strong connection with the industry and emphasises preparation for future careers in the field of early childhood education. Oriented by this vision, the department regards the placement practicum as attaining “the comprehensive learning of students to become professional early childhood educators” (Vocational Training Council, 2017b) instead of solely fulfilling the statutory requirement. Students must complete two compulsory in-service placements – the fieldwork placement and advanced placement – comprising approximately 600 hours of professional training throughout the programme. This number of placement practicum hours is almost double the statutory requirements. Referring to its curriculum, the first fieldwork placement starts in the second semester of the first year of study. It serves as a pre-requisite module of the advanced placement. In facilitating students’ learning, an assigned institution supervisor will work closely with the kindergarten superintendent to monitor their performance. To ensure the placement learning is preparing students to become high-quality early childhood educators, the institution supervisor will continue to assess students’ learning outcomes through individual and group supervision, class observations, poster presentations, lesson plan designs and individuals’ reflective journals. At the end of the placement, the kindergarten superintendent and the institution supervisors will grade students’ performance regarding ‘professional quality and attitude’, ‘lesson design’, ‘the ability of communication and relationship building with the kids’ and ‘classroom management’ to evaluate whether students can achieve their placement objectives and fulfil the vocational requirements and expectations in their fieldwork placement.

The same expectation appears to drive the fieldwork placements institutes all over the world (McFarland & Saunders, 2009; Nickel, Sutherby, & Oliver, 2010; Ohi, 2014; Recchia, Beck, Esposito, & Tarrant 2009; Su-Jeong, Weber, & Soyeon, 2014; Wee, Weber & Park, 2014): offering students valuable field experience so they can learn to be qualified teachers by moving from classroom observers to actors engaged in dynamic teaching. Besides the general institutional questionnaire survey distributed by the council for all the VTC students in different disciplines, to evaluate the placement outcome and efficiency, the department adopted two strategies. First, student feedback and comments were collected using a one-page program survey that had twenty structural questions focused on student self-evaluation, the efficiency of the administration and supervisor, and kindergarten support. For instance, the students were asked to assess; their communication and classroom management improvements, the supervision quality and impact, and their working experience at the kindergarten. Second, after a consolidation of the student grades in a table and statistically comparing the results of past academic years, in a one-off annual moderation meeting, senior management and supervisors review students who have failed and the overall student performances, and then assess their ability to meet industry expectations. Without a doubt, these practices help to depict the general picture of students’ performance in the placement and verify whether their performance is fulfilling the industry’s requirements and needs. However, paradoxically and practically, it is not all that matters because this practice might downplay unique contextual factors that influence students’ performance and the fieldwork placements’ outcome, for instance, stakeholder perceptions (Brown & Danaher, 2008), students’ educational background and working experience (Rouse, Marrossey, & Rahimi, 2012), relationships with cooperating teachers (Johnson, La Paro, & Crosby, 2017) and placement partnership (Walsh & Elmslie, 2005), institution supervisors’ values (Dayan, 2008) and their understandings of assessment (Ortlipp, 2003; 2009), resources of the placement centre (Jensen, 2015) and so on. Therefore, merely evaluating the placements’ quality by comparing the given grades of students’ performance, but not the fieldwork placement itself, unavoidably loses sight of unanticipated outcomes for students, stakeholders’ perceptions and any inherent values in this educational engagement. The urgency of a new form of evaluation is opening up in turn; it should be responsive to various stakeholders and context bound and should override the predetermined objectives or students’ performance, including the placement’s own intrinsic value to the programme.

Evaluation refers to the process of the “purposeful gathering, analysis and discussion of evidence from relevant sources about the quality, worth and impact of provision, development or policy” (Saunders, 2006, p. 198). In other words, oversimplifying the evaluation into distinct conceptual or instrumental uses might be unable to address the issue appropriately (Scriven, 1996). In this regard, this evaluation first deploys a responsive evaluation approach to highlight the methodological direction of its design while searching for a new form of implementing the evaluation process. Then, in order to increase its usefulness and benefit to the placements’ stakeholders, and to avoid positioning the approach in paradigm debates, this evaluation utilises the practical tool RUFDATA (Saunders, 2000, p. 16) to frame the key evaluative aspects accordingly.

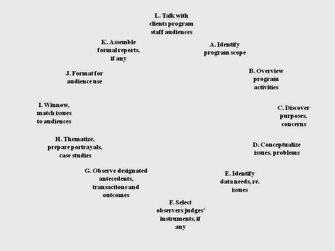

The responsive evaluation approach aims to broaden the scope of evaluative practices with stakeholders’ negotiation as well as to emphasise the value of the existing programme (Stake, 1976). Backing away from emphasising a statement of goals and objectives, evaluation is responsive “if it orients more directly to programme activities than to programme intents, if it responds to audience requirements for information, and if the difference value perspectives of the people at hand are referred to in reporting the success and failure of the program” (Stake, 1991, p. 65). In this regard, this approach offers us a new vision for current institutional evaluations instead of solely assessing programme interventions based on pre-ordained learning objectives. The new form of evaluation could evaluate the effectiveness of stakeholders’ practices, for example, to increase the usefulness of the findings (p. 64) and to report the complexity and multiple realities along with a more conventional description of the targeted programme (p. 72-73). To this end, the produced local knowledge enables practitioners to make the right decision in specific cases (Abma, 2005), and to “help in monitoring the programme, when [but] no one is sure what problems will arise” (Stake, 1991, p. 75). In the meantime, shifting the evaluation approach results in immediate heavy lifting and offers certain changes to methodological decisions and the appropriate steps to follow in design (Mertens & Wilson, 2012). The responsive evaluation approach is no exception. By addressing the power of communication and vicarious experience, in term of emergent evaluation design, the plurality of stakeholders’ values and interests should be implicated at the same time. Originally, Stake (1976) conducted a responsive evaluation involving 12 prominent events organised in an iterative, dynamic and recursive clock-like fashion (Table 1):

Table 1: Prominent events in a responsive evaluation (Stake, 1976, p. 21)

This paper considers these events in framing the evaluation design, where it sacrifices some precision in objective measurement from the positivistic perspective but assumes that stakeholders are groups of people whose interests are at stake. Practically, in the meantime, these events are feasible to process because the evaluation is situated in a specified institution, which is a relatively closed school community that is context-bound and relevant to educational issues in teaching and learning (Stake, 1976).

RUFDATA is the acronym used to frame the evaluation in reification. It has widely been used in framing the evaluations of tertiary programmes over the past decade (for example: Cheung, 2016; Jelfs & Pelly, 2007; Levy, Dickerson, & Teague, 2011; Mukhopadhyay & Smith, 2016; Sherman, 2016). The evaluation is guided by the responsive approach and is categorised into the following seven key realms according to its acronym, namely, reason, use, focus, data, audience, timing and agency, which have been applied to the evaluation object in this case:

1.

Reasons: By reviewing the programme documents and intensively

co-working with people in and around the programme for a semester, the author

identified that the department regards the fieldwork placement as a crucial

learning component for students to learn to be professional kindergarten

teachers. To enhance the usefulness of the evaluation and responding to

stakeholders’ concerns, the author thus introduces the responsive evaluation

approach to guide a new form of work in concerning the merit in fieldwork

placement.

2.

Uses: Internally, the author will report the results in the

department meeting in summer 2018 to assist with department members’ ongoing

quality improvement of the engagement. To share the results with placement

students and kindergarten principals in Hong Kong, the author will publish the

formatted report in a local educational column in summer 2018.

3.

Foci: The evaluation focus was the

responsiveness of the fieldwork placement stakeholders; senior departmental

members, kindergarten principals, fieldwork supervisors and students. After two months (from June to July 2017)

of face-to-face contact with the various stakeholders, it was

found that the stakeholders frequently emphasised that supervision was crucial

in guiding the students to be professional kindergarten teachers. The stakeholders also claimed that supervisors tended to work in dispersed

teams, and each had their own educational visions and supervisory styles. As

the practicum supervisory role

and approach is not well-defined in the departmental placement handbook,

supervisors conduct their supervisory activities based on their personal

opinions, experiences and intuitions. Regardless, as required by the

department, during the students’ 4-week placement to develop their professional

attitude and skills, each supervisor has to have at least: 1. one standardised

3-hour group session each week and; 2. two lesson observations and individual

post-observation conferences. Based on observation and communication with the

stakeholders, the primary

evaluation question ‘How does the supervision develop students’ professional

identity when entering the childcare workforce?’ was

confirmed.

4.

Data and Evidence: In light of the responsive evaluation

approach, the qualitative research method is preferred because case studies of

several students may represent the educational programme more interestingly and

faithfully than a few measurements of all the students (Stake, 1991, p. 73).

Since information-rich cases can generate insight and understanding into the

issues (Creswell, 2008), homogeneous sampling is used, and contact is

purposefully made with the first-year students who have just interfaced with

secondary learning and have just completed their program’s fieldwork placement

in June 2017.

5.

Audience: This evaluation is chiefly responsive to the identified

stakeholders of the fieldwork placement. In the meantime, however, the author

will match information reports and reporting formats to specific audiences with

different formats for different audiences, such as the institution fieldwork

supervisors, the kindergarten principals and placement students.

6.

Timing: Directed by the responsive evaluation approach, the author

has divided the evaluation into two phases: 1) Between June and August 2017,

the author made a plan of observations and a record for all the fieldwork

activities, in an attempt to discover what their value is in students’

fieldwork placement through naturalistic communication with targeted

stakeholders; 2) Between September and November 2017, along with continuing

direct qualitative observations in the naturalistic programme setting, the

author will design the evaluation, collect and analyse the data and prepare the

final written report.

7. Agency: Author has invited stakeholders to co-design the evaluation. However, the participants would maintain anonimity and would only be involved in informal communication for sharing their concerns as requested. After careful contemplation, in my role as one of the fieldwork supervisors in the department, who is responsible for carrying out duties that pertain to evaluation (Lodico, Spaulding, & Voegtle, 2006, p. 322-323), has already built trust with the stakeholders and is acquainted with the intricacies of the placement, the author will be the only internal evaluator in this.

In September 2017, the author interviewed eight selected students to discover how supervisions develop their professional identity during the fieldwork placement. All interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in Cantonese, so the students felt comfortable conversing and expressing themselves in their first language. Interviews were then transcribed verbatim and translated into English for further analysis. Data analysis was situated in an iterative, dynamic and recursive process, in which the author moved amongst data and the evaluative question. Practically guided by the coding steps and process introduced by Creswell (2008, p. 250–253), informational segments were coded after preliminary exploration of the data’s general sense through reading scripts in their entirety and writing memos. After deductively coding the entire text and, later, inductively coding iteratively, similar codes were further aggregated to form four themes and provide information on how supervision develops students’ self-perception of themselves as kindergarten teachers and adapts them to work in the kindergarten workforce:

Even though students have learned a wide range of skills and knowledge in the institution, they have not really reflected on the variety of formed practices that are in opposition to the early childhood professions. Learning to be qualified kindergarten teachers, students showed that their knowledge and skills have been subject to criticism and revision when they discovered a real-life situation in which they failed to respond to the professional requirements or even faced consequences that conflicted with the kindergarteners’ benefit, for instance:

I found that I have overlooked students’ enjoyment but only the musical elements. (Student B)

I discovered that the child might not understand what I mean, and therefore my expressions must be more concrete and include more explanation because they are too young… (Student D)

I have had the impression that all the children were simple-hearted and naïve…however, in the placement I found that they could conflict and struggle with the teachers and the student-teachers… (Student F)

Simply revising their skills and knowledge might not suffice for students’ professional development. Instead, their development depends on whether the dialogue in supervision can produce new insights into other ways of understanding the placement and the practices than their own:

My fieldwork supervisor required me to review the implementation after the lessons and to self-reflect on how I could do it better in the future (during supervision). I found it was good for me…These help me process even deeper my understanding of how classes should be operated. (Student C)

I had never imagined that I suffered in inter-personal relationships in the kindergarten during the placement…My supervisor knows me but still advised me not to be too plainspoken and blunt. I reflected on the interactive process between the children and myself and agreed that children might misinterpret my words and tones and think I was punishing them… (Student F)

Through supervisors’ facilitation, respondents showed that reviewing the challenges of any concerns occurring during their fieldwork placement led them to engage in reflection activities through their first-person interpretation of specific contexts in fieldwork placement. This reinterpretation could inspire students to understand their teachers’ roles and duties in the current placement situation.

Based on the learned knowledge and the reflection of the situation, the students will consolidate all the relevant resources and envision what their behaviour should look like as kindergarten teacher to fulfil both professional requirements and expectations. Before the placement commenced, and before they had even enrolled in the programme, all the respondents already had a perception of a kindergarten teacher:

At the beginning, I thought early childhood education is a woman-oriented industry to transmit knowledge to the children… (Student A)

It was all about ‘Teaching’, which means the mission of kindergarten teacher is to transmit knowledge to the children. (Student G)

I thought the main duty of kindergarten teachers was to look after and play with the children, instead of facilitating their learning… (Student F)

With these perceptions, supervisors’ role should be one of guidance in the respondents’ supervision, helping them envision how a quality kindergarten teacher should be and the difference from their original perception:

When I saw my supervisor’s effort in early childhood education and towards his students, I wanted to improve and be a teacher like him. I asked myself, as a teacher, how much am I willing to spend on my students? (Student C)

I would like to be a kindergarten teacher like my supervisor. She looks like a "kindergarten teacher" because she is so decent and quiet… (Student D)

According to the respondents, richer envisioning helps students to become more familiar with professional ways of facing the complexities in which they are situated and deepens their understanding and reinterpretation of their current position as a kindergarten teacher. For example:

My supervisor let me understand that being a kindergarten teacher is not what I imagined. As a kindergarten teacher, I have to emphasise the children’s strengths and facilitate their growth… Even though their growth is limited by the current Hong Kong situation, I have to treat them like my own children and appreciate their own strengths… (Student B)

This envisioning activity projects respondents’ expectations of what a kindergarten teacher should be like and helps them to improve and judge their current practices, whether correct or incorrect, and even makes it possible for them to change their existing perspective.

While learning to be kindergarten teachers, all the respondents would like to know what the purpose or end result of a kindergarten teacher ought to be. This knowledge is not just a conceptual discussion but an understanding of why that result is desirable both for the academic and professional requirement in professional manners and practices. For instance:

She (supervisor) used to first go through my teaching plan carefully, then give me related suggestions for its correction and discuss the reasons during the supervision. Last time, when I wanted to conduct a programme topic on ‘Cats’, she was against it because she reasoned that I was not situated in an international kindergarten. She let me know that it could cause great trouble if any students got hurt from the kitties in a local kindergarten. (Student A)

Before the placement commenced, I supposed that I had to design three learning objectives in every lesson; at the time, I did not realise that this was too much for a child. My supervisor explained to me that the learning objective should be clear and focused, even though there are just one or two objectives, because as kindergarten teachers, we should not waste any teaching time and it was fine if we could achieve the chief learning goal, even there was just one. (Student C)

According to the interviews, this reasoning process helps respondents to develop and decide the strategies related to educational practices like teaching and learning, classroom management, building relationships with children and so on, to carry out the achievement in their learning and kindergarten operation in a professional way. In contrast, failure in this reasoning process might undermine their professional growth:

I had to design inquiry-based learning activities. My supervisor used to reject my initial design and point out its deficiency without any reasons and suggested improvements during the supervision…I was depressed and incapable of working out the lesson (the following week); I have even asked myself if I can be a kindergarten teacher in the future… (Student D)

Therefore, this reasoning process in the supervision could enhance, or, to the contrary, destroy students’ professional ability to diagnose and solve problems and respond to the professional requirements in a way that preserves an accurate vision of what a kindergarten teacher is and ought to be.

To construe the kindergarten practice appropriately, students must be responsive to the situation without the distraction of self-interest but with professional ethical consideration. That is, students should identify the required conduct and ethical needs and be sensitive to what is morally relevant in the work and the subtle features of the situation:

There was a time, the font size of my teaching plan was inconsistent, my supervisor warned me that as a kindergarten teacher I should be careful-minded, always precise... since then, I treat myself stricter and more harshly. (Student A)

There is an attitude I learnt from my supervisor – as a kindergarten teacher, never give in to children’s threats. For example, some parents might regulate their children’s behaviour by threatening, like telling their children “I will starve you if you keep talking”. This is what I mean by threatening. (Student B)

Professional ethical considerations also refer to non-educational practices, like handling interpersonal relationships in kindergarten and having a deep understanding of teamwork and how they can work with their colleagues and survive in their professional field:

The

difficulty is not related to whether I could teach the classes or practice

certain skills and knowledge, but to the interpersonal relationships in

kindergarten…the relationship refers to the co-operation between teachers… (Student F)

The relationship between colleagues influences your work in the kindergarten, because co-working with other teachers is inescapable. If you work without passion, or are unwilling to exert yourself, the quality of work will be undermined… (Student C)

This cultivation is not a uniform process across all respondents. Instead, it depends on attitudes developed throughout the supervision through the student-supervisor interaction and on how supervisors refine students’ moral perceptiveness. In other words, the process refers to how students care about their duties, cooperation in kindergarten and so on, particularly as principles or regulations cannot function as reliable guides but rely on a complex, developed set of attitudes.

The extended supervisory process that requires the students to review their placement learning was found to develop their professional identity. This process emphasises understanding the past, deliberation on current circumstances, and future expectations for their development as kindergarten teachers. The findings confirmed that supervision was useful in developing the students’ self-perception as kindergarten teachers. In this section, we discuss two necessary improvements to increase the value of the placement supervision that affect both the early childhood teacher educators and the institution: the supervisors’ perspective on the fieldwork placements and the institutional administrative arrangements.

As the purpose of the supervision is to provide a learning platform for the development of a coherent professional identity, guided by their supervisor, students are able to make subtle adjustments to reinterpret the role and duties of a kindergarten teacher. Therefore, the supervisory process should not be limited to one single aspect such as the students’ conduct or their working ability. Instead, supervisors should comprehensively guide the students and help them learn how to be qualified kindergarten teachers. If this is not done, the students may suffer in their developing role as kindergarten teachers:

I think the supervisor could share more of the required attitudes and some related conduct issues in addition to skills and knowledge. (Student A)

Actually, I look forward to exchanging my ideas with my supervisor, any issues related to academics and my lifestyle, and how I can be a good kindergarten teacher. (Student C)

We seldom process in-depth reflection activities during the supervision…Through the reflecting process, at least, I think I can understand how professionals (supervisors) regarded my performance, and how I can improve and become a better kindergarten teacher… (Student D)

Therefore, the supervisors’ perspectives and understanding of the purpose of the placement are vital to the students’ professional growth; however, placement learning is complex. During the placement, students might suffer under supervision and when they are faced with learning difficulties, they could be disheartened. Therefore, teacher educators and/or supervisors need to maintain the students’ enthusiasm (Beltman, Glass, Dinham, Chalk, & Nguyen, 2015) and provide useful and constructive feedback to build student confidence when facing difficulties (Wee, Weber, & Park, 2014). Supervisors also need to support the students and assist them in resolving the feelings of professional inadequacy that arise from stressful situations by encouraging them to learn from these experiences (Lindqvist, Weurlander, Wernerson, & Thornberg, 2017). Second, supervisors also need to continually reflect on their supervisory approaches to ensure they are facilitating the students’ fieldwork learning. As it was found that each supervisor tends to have their own unique educational vision (Dayan, 2008; Ortlipp, 2009), each supervisor’s approach is also different; therefore, placement supervisors must be aware of their own supervisory approach as well as the institution’s mission and culture so as to ensure that they continue to recognise that student inquiry is not the end goal but is an opportunity for the students to have productive and critical reflection (Beavers, Orange, & Kirkwood, 2017; Han, Blank, & Berson, 2017).

The abovementioned findings and their implications link various placement episodes. An integrated supervisory process is therefore needed to ensure students can develop a professional identity that has integrity as various activities co-exist when seeking to build a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the kindergarten teacher and the students. However, the supervisors’ perspectives and commitment to the process are unavoidably subject to the student-to-supervisor ratio:

Taking care of 10 placement students at the same time keeps my supervisor busy. With limited time, she tends to focus on reviewing my teaching plan and offering corrections, rarely exchanging ideas or communicating with me…even though she was not able to answer my questions in depth. (Student D)

More time is needed…If there are more opportunities to share my ideas in the supervision, at the same time, she (the supervisor) could learn more about each student’s ability and strength. For example, I learnt sand art last year and would introduce certain activities in my class, but there is no chance to share this thought with my supervisor. (Student B)

As it is bound by the institutional administrative arrangements, the student-to-supervisor ratio identified here could be a potential barrier to the development of the students’ professional identity through supervision. As trust is essential in any student-supervisor relationship, the limited meeting times makes the supervision process challenging as the supervisor response to the student queries and questions can be undermined (Machado & Meyer-Botnarescue, 2011, p. 71). Although reviewing the student-to-supervisor ratio takes time, at the moment the department needs to improve student-to-supervisor communication so that supervisors can provide adequate advice and feedback on how the students are progressing (Maynard, Paro, & Johnson, 2014); for example, the department needs to consider taking advantage of technology to design online environments where the supervisor and students can easily exchange ideas (Sutherland, Howard, & Markauskaite, 2010). Overall, the values and quality of the supervision is limited to the supervisors’ perspectives about the fieldwork placement as well as the institutional administrative arrangements. Therefore, further evaluations should pay more attention to these factors. At the very least, they might serve as a reminder that any institutional evaluation related to fieldwork placements should not overlook the organisational context and the supervisors’ beliefs and values.

Current institutional evaluation of fieldwork placement used to focus on the students’ performance but not on the value of the fieldwork placement itself. In this sense, it is unavoidably overlooking complexities and losing sight of unanticipated outcomes for students, stakeholders’ perception and any inherent value in this irreplaceable, crucial educational engagement. Hence, practically, the need for a new form of evaluation for the institutional placement is opening up in turn: it should supersede the students’ predetermined performance and focus on the value of the fieldwork placement. Guided by a responsive approach, this evaluation aims to break the usual evaluation pattern and incorporate the programme stakeholders’ current limited understanding about supervision. In this regard, we first sought to revisit the usual institutional evaluative practices and identified senior members in the department, kindergarten principals, institution supervisors and placement students as groups of people whose interests are at stake and as important responsive accounts for the evaluation results. Through constantly working and communicating naturalistically with stakeholders, a new evaluative focus has been established: how the supervision develops students’ professional identity and prepares them to enter the childcare workforce. Based on in-depth interviews, the evaluation results indicated that students’ professional identity is developed by constantly interpreting their experience in their fieldwork placement. This interpretation process is guided by the supervisor and situated in intertwined aspects that help students self-reflect on what they were, envision what they should be, and develop adequate reasons and support for their practices as professional kindergarten teachers. In that regard, two implications for further institutional supervision are raised. First, every departmental fieldwork supervisor should constantly review and reflect on their supervisory activities to consider whether the supervision can lead students to comprehensively and continuously reinterpret their fieldwork experience. If the supervisor over-emphasises any one categorical activity, the student might neglect part of the professional quality that a kindergarten teacher should have. The second insight follows naturally from the first. Because the student-supervisor ratio inescapably influences the contact hours of supervision, the department should further review its fieldwork placements’ administrative arrangement. That is, further actions are recommended to focus on the fieldwork in relation to its institutional context, for instance, to review the supervisor-student ratio, departmental support for the student-supervisor’s communication and the sufficiency of supervisory contact hours to enhance the fieldwork placements’ quality and to nurture the professional kindergarten teachers of tomorrow in Hong Kong.

Cheng Tak-lai is a PhD student in Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University, and is currently positioning as lecturer in Department of Childcare, Elderly and Community Services at the The Hong Kong Institute of Vocational Education. He teaches for the higher diploma program in early-childhood education, and retains an active interest and delivers lectures and fieldwork placement in related areas.

This paper forms part of the author’ study at Lancaster University. The author would particularly like to thanks the students who participated in this study, and Professor Murray Saunders who provided valuable comment on the work.