Anna K Wood, Paul Anderson, Hamish Macleod,

Jessie Paterson, Christine Sinclair,

University of Edinburgh, UK

Dialogue, in all its forms, is widely regarded as being important for learning (Alexander, 2006; Wegerif, 2013) – it provides a way for students to explore their ideas, to clarify misunderstandings and to build relationships with teachers and peers. While there is substantial research on peer dialogue (e.g. Boud, Cohen, & Sampson, 2014; Wood, Galloway, Hardy, & Sinclair, 2014), dialogue between teachers and students in undergraduate education remain relatively unstudied. Recent work has shown how creating dialogue in lectures can support learning (Wood, Galloway, Sinclair, & Hardy, 2018) and Pedrosa, da Silva Lopes, Moreira and Watts (2012) have investigated how university teachers respond to students’ questions. Effective dialogue between teacher and student (defined here broadly as dialogue which supports learning) is often linked to good questions, yet research has shown that while students often do have questions they are reluctant to ask them (Dillon, 2004; Teixeira-Dias, Pedrosa de Jesus, Neri de Souza, & Watts, 2005)). Encouraging questions can help to facilitate effective dialogue, but what happens during the dialogue, (for example, how the teacher responds and how the student feels about that response), is also important, and will influence how likely questions are in the future. For example Maskill and Pedrosa de Jesus (1997) found that if conditions conducive to asking questions were created then students were more likely to ask meaningful questions. Similarly Turpen and Finkelstein (2010) found that the classroom ‘norms’ of the learning environment set-up by the lecturer had an impact on how likely students were to say that they felt awkward asking questions in class. Our aim in this project is to explore students’ and teachers’ experiences of dialogue in learning contexts as well as the questions that triggered them and to use these insights to suggest strategies that can encourage more successful student/teacher interactions.

Fourteen participants at the University of Edinburgh, comprising seven students and seven teachers were recruited from three subject areas: Education, Veterinary Science and Informatics. We purposely recruited a diverse cohort of participants consisting of four academic lecturers, one demonstrator, two PhD student teaching assistants (i.e. seven teachers) and three first year undergraduate students and four masters level students (i.e. seven students). One of the Master’s students was a mature student on an online distance learning programme and one of the teachers was a tutor on the same programme.

Ethics approval was obtained through the ethics committees of each of the three schools involved in the research (Education, Veterinary Science and Informatics). All participants were provided with an information sheet explaining the purpose of the project, how their data would be used and stored and any risks and benefits to taking part. Consent was given by all participants.

Semi-structured interviews took place between March and May 2017 either via Skype, or on the telephone. All were audio recorded and transcription was carried out by a professional transcriber.

Prior to the interview participants were asked to recall an example of a dialogue with a student or teacher that was ‘productive/useful’ and one of that was ‘difficult/frustrating’ which could be discussed during the interview. Participants were also asked general questions about how, when and why they engaged in dialogue with teachers or students.

Thematic analysis was used to identify common experiences of questions and dialogues. Initially the teacher data and student data were analysed separately in order to identify themes for each group. The methodology of Braun and Clarke (2006) was followed. After checking the transcript against the audio recordings, initial coding was carried out by the first author involving highlighting relevant passages and making notes about the key ideas being expressed. These were then collated into a single document and emerging codes were noted. Data extracts and codes were then shared with all of the researchers, and themes, together with detailed descriptions of the themes, developed through discussion. Throughout this stage, the researchers returned to the data to check that the themes were representative of the interviews, so that themes were developed in an iterative process.

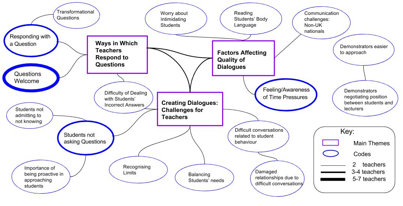

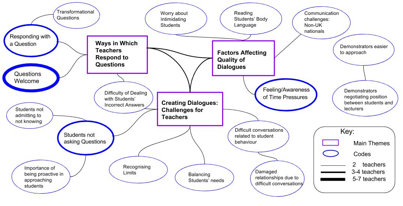

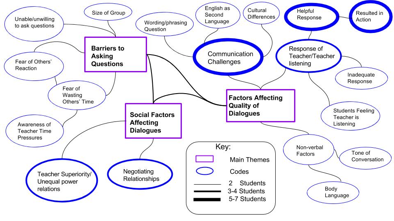

These themes were then loosely grouped into three interlinked main themes which capture the key ideas expressed in the interviews. The resulting thematic maps (figures 1a and b) show these main themes (boxes) and codes relating to those themes (and sub-themes) (ovals). The thickness of the borders of each shape show how common the code was in our data. These figures are presented to give an indication of the range of topics discussed by the participants and possible relationships between the categories, rather than as a rigorous analysis. Further work would be needed to create fully distinct categories which represented the themes. Our aim at this stage of reporting is to highlight broad messages and their implications, to determine what might warrant further study.

1a

1b

Figure 1a. and b. Thematic Maps for a) Teachers and b) Students

During the second stage of analysis, themes that were common in both student- and teacher-interviews were identified.

Overall, both teachers and students reported positive experiences of questions. Students felt teachers were happy to answer questions and the majority of teachers said that questions from students were welcome. This is at odds with research which suggests that teachers in high school are at best ambivalent about questions and at worst find them annoying (Rop, 2002). It may be that we inadvertently selected teachers who were interested in pedagogy and were therefore more welcoming of questions, but this would not explain the positive views of students from across the three schools. It may be that the teaching ethos in higher education (or perhaps specifically at the University of Edinburgh) means that questions are viewed differently. An alternative explanation is that our study focused on questions that are asked in a range of different places, times and modalities, and did generally not take place during class time.

However, all participants also had at least one experience of a dialogue that was difficult or frustrating in some way. These provide valuable insights into the type of difficulties that students and teachers encounter during dialogue and also point to strategies that can help to support productive dialogue. Some of the key themes from these interviews are discussed below.

Many teachers commented that students were reluctant to ask questions, and that they would welcome more questions from students which is consistent with the literature (Dillon, 1988; Teixeira-Dias et al., 2005). There was not a clear consensus for why this might be the case, though some suggested that students didn’t want to ‘lose face’ or were embarrassed.

Losing face was certainly an issue for some students, and was expressed in a number of different ways, for example, one student commented: ‘I feel ashamed to tell him I don’t understand’. Half the students mentioned that the size of the group affected their question-asking, with large groups seen as a barrier to questions ‘I sometimes find this quite difficult due to the size of tutorial groups’. Students also worried that asking their question would provoke a negative reaction, ‘feel your answer will be judged or inferior due to the attitudes demonstrated by students and/or tutors’.

A concern about time and timings was common throughout the interviews. Although students admitted that hearing their peers’ questions was useful, as they often had the same question themselves, they also worried about wasting others’ time: ‘I don’t really like to ask questions that I think that no-one else is interested in cause then it seems like a waste of their time if they’re hearing it.’

Many of the students also perceived that teachers’ time was limited, and this affected when, how and how often they asked questions, for example: ‘Like the lectures are already like rushed so we don’t wanna like spend time on our own questions’.

It is unclear whether this feeling was founded, or whether students were picking up on teachers’ time-pressures and making assumptions about where their priorities would be.

In general teachers commented that questions were welcome but it was clear that time pressures did have an impact, with one teacher commenting that if students asked more questions during lectures it would cause problems given the quantity of material that needed to be covered: ‘there’s not a huge amount of that [question asking] which is good cause it would be very disruptive. And we wouldn’t manage time wise.’

Other teachers commented that they would like more time to be able to have conversations with students.

As previous work has found, the reasons for students being reluctant to ask questions are complex (Watts & de Jesus, 2007). Our finding that students worried about taking time to ask questions during the lecture may be a specific example of work in the literature which suggests that students were concerned about how their questions will be received by teachers.

For both students and teachers, problems with effective communication were common causes of concern. For students in particular a wide range of communication difficulties were discussed. A student for whom English was not their first language commented: ‘I know what I mean but I can’t express it because maybe the lack of English knowledge’. For other students it was the cultural differences that were more prominent. A Chinese student said: ‘One of the most obvious culture differences appears on thinking method. Roughly speaking, western people are more explicit and eastern people are more implicit. When I want to ask questions to a western teacher, I need to find a suitable scale between these two’. It is commonly assumed the Asian students are more reticent and passive learners in classroom settings – yet as (Cheng, 2000) argues, we should take care not to over-generalise. Our findings highlight that both cultural differences and language knowledge can play a part in creating communication challenges.

Communication challenges were not limited to non-UK nationals. A number of home students commented that wording their question appropriately was something that they worried about. For example: ‘If I am entirely uncertain then usually I struggle to put together an email which is structured and makes sense.’

For teachers the main concern about effective communication was around understanding students with strongly accented English. The University has a large number of students from Asia and teachers were particularly worried about not causing embarrassment when they didn’t understand what the student had said.

Both students and teachers had expectations regarding teacher-student interactions, which were sometimes at odds with what actually happened. For example, some students attributed problems that arose to the asymmetry in the teacher/student relationship. This was particularly the case for first year students grappling with the transitions from school to higher education, from childhood to adulthood. One first year student commented:

Regarding conversations with teachers the only thing I would change is the manner in which they sometimes address their students. It shouldn't be an assumption of superiority (understandably they are in a position of power, but it is important not to abuse it).

Others felt that they weren’t being treated as adults, despite being told by lecturers that they were no longer at school.

A few students complained that teachers were more keen to talk than to listen, perhaps also indicating a mismatch between expectations of teacher student interactions:

I think they should just answer our questions and…listen to what we have to say if we have any more questions cause they tend to have a spin off of the subject..

But other students mentioned how much they valued the feeling that teachers were listening to them. One student commented that ‘my personal tutor played a listener more than an advisor, and that's what I need at that time’ . Teacher-student relationships at university level have received little attention in the research literature, (Hagenauer & Volet, 2014) yet they clearly play an important role in creating and maintaining effective dialogues.

Some strategies for enabling successful dialogue were raised by teachers and students during the interviews. These have been combined with conclusions derived from the key themes discussed above to produce guidance that points both students and teachers towards more effective communication.

Students:

1. Don’t be afraid to ask questions. It is likely that other students have the same question. Teachers are happy to help and see it as part of their job. It is also very useful for them to know which areas students need more support with.

2. Help teachers out if you don’t understand something. If you don’t tell them, they probably won’t know.

Teachers:

1. Be proactive – students may have difficulty approaching you, but will be happier to talk if you approach them.

2. Ask open questions to check understanding. This helps create a dialogue rather than a monologue.

3. Make your expectations about questions clear to students. Explain that questions are welcome and are an essential part of learning.

4. Be clear about when, where and how you prefer to be approached, and also the time-scale in which they can expect a reply.

Interviewing a diverse cohort of students and teachers has led to a range of insights into the difficulties of starting dialogue and barriers to effective dialogue. We noted issues with students feeling embarrassed to ask questions and worries about wasting others’ time. We found that both UK and non-UK students were concerned about communicating effectively and that students valued feeling that they were being listened to. A common theme in these findings was the importance of the student/teacher relationship.

Our suggested strategies are designed to support both students and teachers to have effective dialogues. Yet, we recognise that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. As one teachers commented:

I see myself as trying to strike the balance of being sensitive to a student not being confident, but at the same time trying to encourage them to be involved and to ask questions.

This was a small scale study which has raised a number of interesting avenues for future work. For example, although our study was cross-disciplinary it was too small to explore any differences in detail. A larger study could investigate disciplinary differences in the way that dialogue is experienced and whether this is due to teaching methodology or type of content. The role of the learning environment could also be explored; our data from laboratory demonstrators hints that these environments may be more conducive to effective dialogues, but they may also need distinct strategies to involve all students. Again, a larger scale study could explore these issues.

Anna Wood has a background in Physics and is currently a researcher in the Centre for Research in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh. Her research interests include dialogue in learning and the use of technology in large undergraduate science classes. Email anna.wood@ed.ac.uk Twitter: @annakwood

Paul Anderson is a Senior Research Fellow with the School of Informatics at Edinburgh University. In addition to his Informatics research, he is particularly interested in the teaching of computer programming. Email dcspaul@ed.ac.uk.

Hamish Macleod is an Honorary Fellow in the Centre for Research in Digital Education, Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 8AQ. He is a past teacher on the MSc in Digital Education with particular interests in narrative, and game-informed, approaches in learning. Email : H.A.Macleod@ed.ac.uk.

Jessie Paterson is a Lecturer in Student Learning at the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh, Easter Bush Veterinary Centre, Roslin, Midlothian, EH25 9RG. Email: jessie.paterson@ed.ac.uk. Special interests include: student academic support, professional skills and staff development.

Christine Sinclair is Programme Co-Director for the MSc in Digital Education, Moray House School of Education, St John’s Land, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 8AQ. Email: Christine.Sinclair@ed.ac.uk. She is particularly interested in dialogic approaches to teaching, student experience, and academic writing, all with a special emphasis on digital environments.