Ruth Pickford, Leeds Beckett University, UK

In the UK in the last two decades there has been a significant movement towards recognising and rewarding teaching excellence, drawing upon proxy metrics as the basis of national league tables, the UK Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework (TEF), and institutional funding. This, in turn, is increasingly impacting on institutional strategic plans, the specification of institutional key performance indicators (KPIs), reward schemes and promotion criteria. Globally, other nations are adopting similar strategic approaches. While currently developed for use in the UK, because the model described in this paper draws upon significant international scholarship, it is argued that the model has the potential for a more global reach.

Interventions to teaching, curriculum and learning environments that are developed independently largely fail when they do not use a holistic model to achieve teaching excellence. There is a growing imperative for institutions and the sector to think synoptically about teaching excellence to enable development of sustainable institutional and course level strategies. The aligned model proposed here will enable the development of holistic strategies which will support consistency within, across and between institutions.

As in many nations, the UK is exploring reliable metrics that could enable judgment to be made at an institutional level to gauge comparative teaching quality. In the UK, Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) metrics are balanced by the use of contextual statements, and individual universities are benchmarked against others that serve similar constituencies and have similar missions. The UK TEF is currently based on metrics and a supporting narrative at the institutional level. The metrics in use, measured over the three most recent years, are: 1. student non-continuation (as measured by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA)); 2. elements of student satisfaction (as measured by the National Student Survey (NSS)) and 3. graduate outcomes (as measured by the Destination of Leavers in Higher Education (DLHE) survey). A key outcome of the concentration on the TEF, in the light of the relationship between the TEF, reputation and funding, is an enhanced focus on maximising performance in these three important areas, which in themselves contribute to enhancement of practice. There is considerable criticism of the TEF and the choice of TEF metrics in the sector (Gibbs, 2017; Derounian, 2017). Criticisms include the assertion that the proxy metrics and methodology do not validly assess teaching excellence, that there is a false underpinning presumption that a university experience should be a homogenous product and that not all students aspire to graduate jobs, and that institutional scores can hide wide departmental differences, (which is leading, in the latter case, to the introduction of a subject-level TEF (Department of Education, 2017a)) .

However, a pragmatic response is for the sector to take ownership of the concept of teaching excellence and to develop a sustainable, research-informed and evidence-based model of teaching excellence. Developing a shared, robust model will empower institutions to respond to, rather than react to, ongoing changes in external requirements and metrics, whilst at the same time supporting course teams to develop meaningful enhancements to their practices. The model will also enable consistent communication between different areas of a university and support internal and external collaboration.

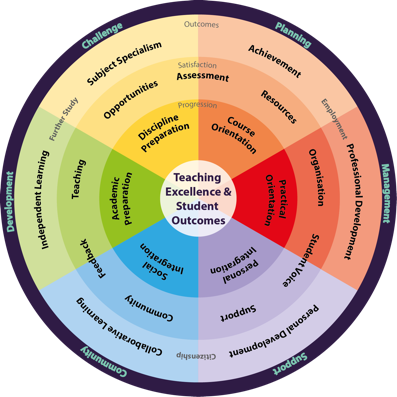

The model I propose here (Figure 1) holistically aligns the elements of an excellent taught experience.

Figure 1 The Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Wheel

Student engagement is variously described in an extensive literature review of this area (Trowler, 2010), but central to this model is the thesis that engagement is a student owned concept. Learning and teaching strategies that treat students as a homogenous mass are likely to be less successful than those that recognise that diverse students are motivated by different goals. Recognising that the ways in which an individual student will choose to engage will be determined by personal goals, individual values, varied expectations and alternative perspectives is fundamental to modelling teaching excellence.

As student goals vary, so their approach to engagement will vary. Students motivated to achieve a higher qualification or professional development, for example, may especially value a well-planned and managed course. Students primarily motivated to develop personally or to learn collaboratively may particularly value feeling a member of a supportive course community. Students motivated to become independent learners or subject specialists in whatever discipline they are studying may be more likely to value a developmental, challenging course. If we wish to leverage student engagement, we need, as universities, to provide engagement opportunities that align with student goals.

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) can provide these appropriate opportunities for student engagement through focused, holistic design of curriculum, learning environment and teaching approaches (Pickford, 2016). The proposed model (figure 1) identifies six related elements:

A course strategy that focuses on a well-planned and challenging curriculum, a managed and supportive learning environment, and on developmental and collaborative teaching approaches can effectively provide opportunities to meet the collective goals of a diverse student cohort.

The proposed model holistically aligns the elements of an excellent taught experience. Since it is argued that all elements of teaching excellence are interdependent, the model is presented as a wheel arranged around these six key elements aligning to students’ specific orientations towards their learning and towards the ways students look to engage.

Excellent course planning requires a curriculum focused on course orientation and induction, constructive alignment of assessment and resources, and a clear and transparent route to achievement of a qualification (Biggs, 2003; Boud & Falchikov, 2006).

Excellent course management requires a professional learning environment focused on practical orientation to the Higher Education Institution (HEI), the locale and the community, providing day-to-day organisation, listening and responding to the student body, and establishing professional expectations and behaviours (Kandiko & Mawer, 2013).

Excellent student support requires an inclusive learning environment focused on personal integration of all students into their course, valuing and promoting individual student perspectives, and providing personalised academic support and guidance for each student to develop individually (Thomas, 2012).

An excellent learning community requires a focus on social integration, encouraging students to feel a sense of belonging and to learn with and from others through teaching approaches that involve regular interaction, integrated feedback, and opportunities for students to develop as collaborative learners (Wenger, 1998; Vygotsky, 1997).

Excellent student development requires offering teaching approaches that prioritise students’ academic preparation and academic literacies, thought-provoking teaching and timely, formative, feedback that empowers students to become independent learners (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006).

Providing excellent student challenges requires a curriculum designed to prepare students for studying the discipline, provides stretching learning opportunities and assessments, and opportunities to specialise, empowering students to become subject specialists (Scager, Akkerman, Pilot, & Wubbels, 2014).

This model starts by considering, in turn, the constituent elements of practices that are associated with the ongoing imperatives of fostering excellent student progression, satisfaction and student outcomes, and proceeds to explore the relationships between these.

One major UK and global focus is ensuring student progression. Student non-continuation on a course is complex and multi-faceted, often resulting from factors outside an HEI’s control. However, there is an ethical, financial and reputational imperative on universities to ensure students that enrol on their courses are provided with the information, support and skills to be successful. Student progression is underpinned by effective orientation, integration and preparation practices (Whittaker, 2008). New students need to be provided with opportunities to orientate to practical and course requirements, to integrate personally and socially, and to be prepared academically and disciplinarily for their course. These elements form the foundation of a student’s experience and the basis of the model (inner ring).

A second major UK and global focus is on student satisfaction. The NSS, completed by UK undergraduates part-way through their final year, has grown in significance since its introduction in 2005 and now features strongly in most university league tables as well as in the TEF. The NSS was changed in 2016 to reflect advanced thinking about what satisfaction comprises, and questions were revised and new banks of questions relating to student voice, community and learning opportunities were added. The NSS measures a student’s satisfaction with the transactional, emotional and academic elements of their experience. Students need to be provided with opportunities to engage transactionally through well-aligned, well-managed courses, to engage emotionally as a member of an inclusive, supportive learning community, and to engage academically with stimulating learning opportunities. The model maps NSS question banks against the foundations of progression.

A third UK sector focus is on graduate outcomes. The DLHE measures numbers of students in employment, graduate employment, and further study six months after graduation and is currently the only outcome proxy measure used in the TEF. Whilst it is reasonable and pragmatic for a teaching excellence model to recognise that excellent teaching may contribute to student outcomes, it is imperative to recognise both that there are other factors that have more influence on employment (Blasko, Brennan, Little, & Shah, 2002), and that a broader definition of student outcomes is required in any model of teaching excellence. Whether or not an outcome is successful depends on a student’s individual goals (Chan, Brown, & Ludlow, 2014). In the proposed model student outcome is interpreted broadly around three domains: the professional, the personal and the intellectual. Individual student goals are wide-ranging relating variously to achievement of a qualification, professional or personal development, becoming a collaborative or independent learner, or a subject specialist. The model maps student outcomes against progression and satisfaction, drawing out the relationships between each.

This model has been primarily developed as a framework for enhancement rather than to align with current TEF metrics. The latter would be short sighted, not least because the current TEF metrics will change as new measures are developed and piloted (Department of Education, 2017b, 2017c). More importantly, however, a model developed principally for this purpose, without its roots in pedagogic research and practice, would be of little value to an academy bombarded with initiatives and it would (deservedly) be paid little more than lip-service. However, starting from a consideration of diverse student goals and the elements of good curriculum, learning environment and pedagogic design, the model provides a basis for holistic approaches that can underpin successful student outcomes.

If we had set out to maximise performance against the current TEF metrics, then we may have reached the same place. Successful outcomes for TEF metrics can only be achieved if these are aligned with student goals. It follows that a framework to support maximisation of these metrics necessarily requires alignment of the components of Teaching Excellence (progression, satisfaction and student outcomes) with appropriate engagement opportunities (through planned, challenging curricula, managed, supportive learning environments and developmental, collaborative teaching approaches) that in turn align with students’ personal goals.

It is proposed that this model can be effectively utilised by institutions if it is used not just as a tool of analysis but as a tool for planning by key stakeholders. Individuals, course teams, teaching and learning directorates, academic services and Deputy Vice Chancellors (Learning and Teaching) can use this framework to holistically design, plan, manage, monitor, evaluate and enhance courses. TEF metrics can be used developmentally to identify specific elements of each course that are meeting or failing to meet their students’ requirements. By identifying, for example, specific NSS questions that are not meeting desired benchmarks, it is possible to extrapolate to related areas of progression and outcomes.

In conclusion, this model, underpinned by valuing students as individuals motivated by personal goals, the concept of student-owned engagement, and by the scholarship of integration, explores how information already available to institutions from the data they hold and use can successfully be aligned with what decades of research tell us about student motivation, engagement and outcomes. The model can be used to produce a positive impact in terms of not only demonstrating teaching excellence but actually putting into practice pragmatic and measurable activities to achieve it. The model is currently being systematically evaluated through its roll-out across a large UK university where it is being used as the scaffold for the Institution’s 2016-21 Education Strategy. In 2016/17, there was an institution-wide focus on the six elements of progression, and in 2017/18 the focus is on the elements of student satisfaction. A full evaluation of the institutional impact, including case study vignettes, will be available in 2019/20.

Alongside this model of Teaching Excellence, a related model is under development that focuses on Teacher Excellence – the excellence of individual teachers – and builds upon staff motivations to underpin a professional development strategy that enables and empowers colleagues to achieve successful outcomes for themselves, for their universities and for the sector.

Professor Ruth Pickford is Director of the Centre for Learning and Teaching at Leeds Beckett University. She is a UK National Teaching Fellow and a Principal Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Biggs, J. (2003). Aligning teaching for constructing learning,. London: The Higher Education Academy.

Blasko, Z., Brennan, J., Little, B., & Shah, T. (2002). Access to what: analysis of factors determining graduate employability. London: HEFCE.

Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (2006). Aligning assessment

with long term learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4),

399-443.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930600679050

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Chan, R., Brown, G. T., & Ludlow, L. (2014, April). What is the purpose of higher education?: A comparison of institutional and student perspectives on the goals and purposes of completing a bachelor's degree in the 21st century. Paper presented at the annual American Education Research Association (AERA) conference, Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from https://www.dal.ca/content/dam/dalhousie/pdf/clt/Events/Chan_Brown_Ludlow(2014).pdf.

Department for Education (2017a). Teaching Excellence Framework: Subject-level pilot specification. July 2017. Department for Education [Online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/629976/Teaching_Excellence_Framework_Subject-level_pilot_specification.pdf [Accessed 25 September 2017].

Department for Education (2017b). Teaching Excellence Framework: Lessons Learned. Summary Policy Document. September 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643701/TEF_Lessons_Learned_Summary_Policy_Document.pdf [Accessed 25 September 2017].

Department for Education (2017c). Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework Specification. [Online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teaching-excellence-and-student-outcomes-framework-specification [Accessed 11 October 2017].

Derounian, J. (2017). TEF – Tiresomely Extraneous &

Flawed. Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching, 10(2).

doi: https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v10i2.496

Gibbs, G. (2017). Evidence does not support the rationale

of the TEF. Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching, 10(2).

doi: https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v10i2.496

Kandiko, C. B., & Mawer, M. (2013). Student Expectation and Perceptions of Higher Education: Executive Summary. London: King’s Learning Institute.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006), Formative

assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good

practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Pickford, R. (2016). Student

Engagement: Body, Mind and Heart – A Proposal for an Embedded Multi-Dimensional

Student Engagement Framework. Journal of Perspectives in Applied

Academic Practice, 4(2).

doi: https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v4i2.198

Scager, K., Akkerman, S. F., Pilot, A., & Wubbels, T.

(2014). Challenging high-ability students. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4),

659-679.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.743117

Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in Higher Education at a time of change, What Works? Student Retention and Success, Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Trowler, V. (2010). Student Engagement Literature Review. York: Higher Education Academy. Available online:

https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/studentengagement/Research_and_evidence_base_for_student_engagement

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning,

Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Whittaker, R. (2008). Quality Enhancement Themes: The First Year Experience – Transition to and during the first year, Quality Assurance Agency Scotland.

Vygotsky, L. (1997). Interaction between learning and development. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York.