Josh Brown, Stockholm University

Federica Verdina, The University of Western Australia

While it is undeniable that casualisation is a pervasive feature of the contemporary higher education landscape in Australia, little research has investigated how casual contracts and their widespread use have impacted staff's expectations of their role, or the way teaching itself is affected[1]. An earlier study by Nettelbeck, Hajek and Woods (2012) made the point that casualisation is a "profoundly negative trend" (p. 1) and that a "re-professionalization process has begun" (p. 1). Although there are "strong currents of resilience" (p. 1), casualisation of the academic workforce does not seem to be disappearing anytime soon.

This paper responds to previous investigations of sessional staff in general (Bryson, 2013; Nettelbeck et al., 2012; Andrews et al., 2016; Eagan, Jaeger, & Grantham, 2015; May et al., 2011) to look more specifically at how the expectations of language studies staff on short-term contracts are affected, and what implications (if any) these contracts have for how they approach their teaching. Using both quantitative and qualitative data, it focuses on language-teaching academics as a case-study to investigate the way in which staff approach their teaching when their employment is, as is often the case, only for one semester.

There are three motivations for this paper. The first is the growing casualisation of the academic staff in Australian universities, a phenomenon which is part of a broader trend of increased casuals in the national workforce (Sheen, 2012). Figures show that over the year 2013, the proportion of casuals rose 17.4 per cent to 22,958 full-time equivalent staff at universities in Australia (Lane & Hare, 2014).

A second motivator for this research is a distinct lack of information in the literature around sessional staff with any focus on language departments. Much of what has already been written with relation to casual staffing levels covers various, often unrelated, aspects of casualisation, such as job insecurity (Cahir, McNeill, Bosanquet, & Jacenyik-Trawoger, 2014), the transition of Australian academic staff levels to a more casualised workforce (Bexley, James, & Arkoudis, 2011; Nettelbeck et al., 2012), casualisation as a symptom for the broader ills of universities (Hil, 2012) or the progress in providing support for sessional staff (Bryson, 2013, with a UK focus).

Thirdly, in a publication of 2012 entitled What place for sessionals in languages and cultures education in Australian universities? A first national report, Ferrari and Hajek highlight the importance of getting a better understanding of casuals in language departments. This report was the result of a national forum and workshop held specifically for casual staff in Australian universities at the first national colloquium of the Languages and Culture Network for Australian Universities (LCNAU) in 2011. In addition to providing a first overview of the general characteristics of these staff and their backgrounds, the report notes three areas where better support is needed for sessional staff: teaching, the university environment, and academic progression and career development. Another goal of our paper was to supplement this data by providing qualitative feedback from casuals themselves.

This article takes up the foundational work from these earlier studies to look at what effects, if any, short-term contracts have specifically on the expectations of sessional staff, and how this might impact their teaching.

In order to gather data about sessional staff, the expectations they hold, and how they approach their teaching, an online survey was distributed to the majority universities in Australia in October 2015 using the software Qualtrics. The survey included 21 multiple choice questions and four open-ended questions. The rationale for the kinds of questions included in the survey was guided by our research goal of providing both a snapshot of the current staff teaching in Australian language departments, and, more importantly, by a desire to elicit a frank response about their expectations from the courses they teach. The survey was divided into three sections to compile information for a demographic profile of sessional staff, their teaching and their teaching expectations. Responses were completely anonymous. Any staff member who was employed on a sessional or casual staff contract in a language discipline at an Australian university (at the time that the survey was open, for a period of 5 weeks) met the criterion to complete the survey. An explicit aim of the study, as indicated to participants in an information sheet on the survey's landing page, was to gain a deeper understanding of the expectations that sessional staff hold. The survey and its distribution were approved by Human Ethics in the Office of Research Enterprise at the authors' home institution. Despite having emailed heads of language departments individually and distributing the survey link via the mailing list of the professional organisation Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities (see Hajek, Nettelbeck, & Woods, 2012 for further details), our response rate remained relatively low. At the time of the close of the survey in early November 2015, a total of 59 responses had been returned, with data from all Australian states and territories apart from the Northern Territory and Tasmania (one respondent's geographical location was not disclosed). Given the lack of official statistics available concerning the number of casual staff in Australian universities, and the fact that the data which are available are not further classified according to discipline, even an estimate of the total population from which our sample is taken would provide an unreliable approximation. Out of the 43 universities in Australia, responses were returned from 17 of them. Four respondents reported having affiliations at two universities. Nevertheless, this rate still elicited slightly more responses than those collected in Ferrari and Hajek's 2012 study, which included 55 responses. Since there was no comprehensive list of universities where languages are taught in Australian universities, we created a list of all language departments by searching department websites in order to target specific universities. We then identified the associated Dean or Head of School in which language departments were located, to whom we sent our request that the survey be distributed to all casual staff. Making generalisations about all sessional staff from our data is therefore problematic, but they still provide an insight into the expectations of language teaching staff as a case-study of this specific cohort of casual workers.

The data are presented below. Our methodology in analysing the results has been two-fold. First, a general profile of our sample is presented, highlighting some demographic characteristics of casual workers and their employment conditions: their current position, their teaching experience and which teaching activities they engage in most. The second part looks at the four open-ended questions of the survey, which were designed to elicit more specific information about sessional staff, how they approach their teaching and their expectations from their employment on a short-term contract. This section draws on the qualitative data from our sample, which we felt provided a clearer picture of the cross-section of casuals in language departments over statistical results.

Our data come from universities in the majority of states, including Victoria (25 responses), New South Wales (14), Western Australia (7), Queensland (6), South Australia (4), ACT (2), and one respondent did not disclose their location. In line with May's (2011) nationwide research, according to which "casual academic staff are amongst the highest qualified in the Australian workforce" (p. 3), respondents in our sample also showed high levels of academic qualifications. When it comes to their current position, almost half the participants (46 per cent) are enrolled in a PhD or MA programme, 7 per cent are Early Career Researchers and the others fall into some other category; for example, they have just finished an MA or PhD and are considering what to do next (12 per cent), or they have abandoned a full-time academic career and they are now teaching at a university, privately or at school (19 per cent).

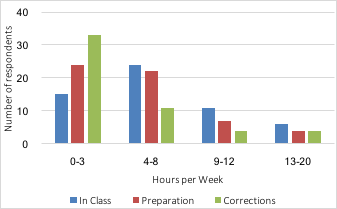

Since sessional staff carry out a number of activities related to teaching, we were interested in verifying where the majority of casual staff spend their time and how this impacted on the way they perceived their role. Respondents were asked to select how many hours they spend in class, preparing for class, and marking corrections. These data are shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Time spent in class, preparation and marking corrections.

Casuals in our sample devote between one and twenty hours per week in one of the three activities listed above. The majority of sessional staff teach no more than eight hours per week.[2] A notable portion are also teaching upwards of 10 hours per week. With regard to demands on time, a majority of respondents reported working elsewhere in addition to university teaching (54 per cent), in sectors ranging from education, research assistance, private tuition, translation and interpretation, to publishing, administration, hospitality and business. This raises questions not just about underemployment for casual staff, but also the way in which casuals manage their teaching and non-academic employment. Our respondents seem to show an overall high level of satisfaction. When asked the question "In general, are you happy to have a sessional contract", 11% were very satisfied, 67% were satisfied, 16% were dissastisfied and 7% were very dissatisfied.

Our survey also addressed the question whether sessional staff were offered a range of teaching or whether they were employed to undertake one type of teaching activity. Perhaps now more than ever, it is essential that sessional staff enrolled in a postgraduate qualification graduate with a range of teaching experience if they are to be competitive in the academic job market. As can be seen in the following figure, the vast amount of activities taught by casuals were tutorials (93 per cent), with only slight percentages also teaching lectures (29 per cent) and workshops (21 per cent).

Figure 2: Time spent in various teaching activities.

Although the above figure indicates that just under a third of casuals in our sample had experience presenting lectures, the majority of their labour is expended teaching tutorials. This finding has important consequences for the kind of professional formation being offered to sessional staff, particularly when the probability of obtaining a permanent position is increased by showing teaching ability across a range of activities. The reverse of these statistics should also be taken into account, particularly with regard to lectures. That is, the majority of lectures (71 per cent) are still taught by tenured staff. The finding may also have important financial implications for the well-being of sessional staff, since lectures are typically paid at a higher rate than language classes and tutorials.

The four open-ended questions discussed in this study were the last questions posed in our survey. They are also the questions which elicited the richest insights into how sessional staff are treated, and feel they are being treated, in Australian language departments. Respondents provided lengthy comments to all four questions. In total, we received 146 written comments to the following four questions:

Question 21.

If your contract is offered on a semester or yearly basis, does this have

any implications for the way you approach your teaching? If yes, please

explain.

Question 22.

Did you receive a programme for the course you taught, or were you expected

to make changes or write it yourself? If so, how much in advance were you

expected to start working on it?

Question 23.

What expectations about teaching did you have before you started this job?

How have these expectations been met?

Question 24.

Are there any other comments you would like to make about your sessional

employment?

We have focused on responses which provided quality feedback and which were longer rather than shorter (thus providing greater detail). The comments were coded following traditional guidelines for qualitative research in languages education (Zacharias, 2012). Brown and Rodgers (2002, p. 64) highlight the importance of defining a coding system that provides a clear, unambiguous, and in the end useful way to classify qualitative research data. In our sample, data elicited from these open-ended questions were coded according to four general themes which emerged most clearly from the responses we received. These four themes are: approaches to teaching; expectations to curriculum change; expectations about teaching, and; general comments about sessional employment. For example, any comment which spoke most directly to concerns about contract length was placed in the first theme. Any comment which related most to expectations regarding the course programme and curriculum changes was placed in the second theme etc. Long responses which could have been classified into two (or more) themes were identified, and then separate parts of the response were quoted in different themes. We deal with each of these themes in turn below. Casuals expressed a variety of responses to these open-ended questions. Since our aim has been to show the range of experiences casuals are currently facing, we focused on a range of comments that were used in the analysis below. We have also sought to highlight commonalities in the comments received. The aim behind this approach was to show the broader patterns that emerged to all questions, which help to highlight the persistent problems that sessional staff face.

A clear observation that can be seen throughout the comments concerns the question whether staff received a programme or were expected to make changes. This, in turn, highlights the reductive effect short-term contracts are having on the time devoted to teaching and preparation. The general theme is not one of neglect of teaching responsibilities, but rather difficulty concerning future planning and job security, as can be seen from the comments below:

A yearly contract, however, would provide me with more time to plan any feedback from the students and an appropriate response to it (…) It could be done in a better manner, if I had more time to plan it.

I will focus on my teaching rather spending time looking for more positions.

In my opinion, being offered only semester contracts is an issue since I never know whether I will be offered more hours in the next semester. It affects my teaching first because I am not as involved as I would be if I had longer contracts, and also because I am worried about the student experience survey that will partly determine my next contract(s).

The comment immediately above hints at a distancing from the engagement with the practice of teaching itself - a revealing statement that is not often articulated since, as the person reports, future employment may be contingent upon a positive assessment by students. This was a sentiment expressed strongly by many respondents in our sample. Since casual contracts are often only for one semester, many respondents wrote that they feel pressure to focus on receiving favourable teaching evaluations:

I feel pressure to be 100 per cent perfect all the time, in order to get another contract.

What is particularly worrying are cases when the decision to re-employ a particular person is largely dependent on student satisfaction surveys, rather than qualifications or ability to perform teaching effectively, as reported below:

Because my contract depends on student satisfaction, teaching is more stressful, I tend to overwork in order to achieve good evaluations, despite 17 unbroken years at the University and ten years of previous teaching experience.

I try to ensure that I keep the classes engaging and interesting so that the students are happy and I will be invited to teach the next semester/year.

Teaching evaluation is undoubtedly an important part of all university education in the contemporary higher education setting. Yet the comments above seem to show an insistence that this is one of the few criteria upon which a renewed offer of employment can be made. It is often the case that sessional staff's energies become concentrated into ensuring student satisfaction with the teachers themselves, rather than on other factors (such as the length or breadth of a unit, overall content or teaching activities).

Another observation that has emerged from our sample is the distinction between respondents who were expected to make changes to unit outlines, and those who were not. In many cases, it is unclear whether this work is paid employment or an implicit understanding between the unit coordinator and sessional staff member that the work be undertaken outside the period of employment. There may be cases where a sessional staff member is also a unit coordinator, but this was not a question asked in our survey. An overarching point made here was that casuals would have liked to be more involved in designing the units they teach. The comment below exemplifies well those cases where tutors responded that they would prefer to be (more) involved in course design, but were not able to do so:

I was given a program, and expected to follow it precisely. I am not expected to make changes to it, so I only vary the manner in which I transmit the content to the students... Even though sometimes I would love to have a say on the content and change it!

One respondent mentioned that there exists a university policy to distribute a programme to tutors in advance of the start of the course (the first below). In contrast, a group of respondents reported that they do not have the freedom to make any changes at all:

I received the programme well in advance, as this is university policy. I have occasionally been consulted in the preparation of assessment tasks, which occurs at least a month before the teaching begins.

I have no participation in the course conception.

I would have liked to have updated the reader if it wasn't already published.

I received a detailed programme which I am expected to follow to the letter.

I was given a very structured programme which included even the activities which were to be done on each day.

The lack of involvement that tutors reported in helping to devise the programme that they would be teaching points to a lack of flexibility and understanding of what drives sessional staff to teach (see also Leigh, 2014). Conversely, no one reported that they did not want to be involved in designing curricula. One respondent noted that "I find it very hard to use a programme that someone else wrote without having the opportunity to give a contribution. Teaching a language can be a very personal experience".

On the other hand, other respondents stated that they did enjoy a certain degree of flexibility in their teaching. In the case of the first comment below, this was paid work:

I'm free to choose my own organisational and pedagogical approaches.

I'm able to make changes to lesson plans if I want.

In all the units I have taught over the years, there has been some structure provided, and also room for adaptation or creativity.

I received many opportunities to be involved in curriculum development and have often given guest lectures.

These comments are encouraging. In this respect, the start and end dates of individual contracts simply do not leave enough time for course preparation for the earlier comments. Respondents noted that they were asked to prepare for the course at various times before the start of their contract, including one respondent who received a month's preparation, but the most common experience was to be informed a week or two beforehand (let alone given appropriate access to teaching materials and to online learning management systems). One comment alarmingly reports: "I was provided [a workbook] the week that classes started (too late in my opinion)". The immediate effect of the lack of involvement in course design, as well as short-term notice, is an overall degradation of the quality of teaching itself, compared to what otherwise would have been achieved. Comments in this vein were made by a previous president of the Modern Language Association in America in a publication entitled The Real Language Crisis:

in the context of a general casualization of the academic workforce, reliance on non-tenure-track faculty members is particularly high in second-language instruction. Higher education administrations target the languages because, in terms of employment status, many language instructors are among the most vulnerable. It cannot be repeated often enough that this shift to a contingent faculty has a deleterious impact on the quality of student learning because it degrades the working conditions of instructors. (Berman, 2011)

Similar comments around the degradation of higher education due to casualisation can be found in Gill (2009), Hil (2012) and Warner (2015). As the data from our sample show, the variety of conditions and expectations levied on casual staff means that expectations about how teaching is to be carried out are not consistent across the country, and make it difficult to plan teaching in specific contexts. The lack of guidelines and policy that characterises sessional staff teaching means that expectations about the course, university administration and conditions are unpredictable and, ultimately, disappoint those staff who dedicate themselves so tirelessly to support it.

Question 23 in our survey went to the core of the expectations which casual staff had about their role and their teaching, specifically about cases when they knew they would be on a short-term contract. Respondents reflected on their expectations in a variety of comments, which we were then able to classify according to five general areas according to common traits. These traits included expectations on student motivation, workload, a sense of belonging to a disciplinary culture, rate of pay, and conditions.

The main concerns raised by our sample reflect broader questions about how casuals' expectations of student motivation were met, or in certain cases, only partially met. Some tutors had begun university teaching after a period of working with high-school students, and were disappointed that the motivation of tertiary students was not higher:

I thought the students would have been more motivated.

I think I expected the quality of student engagement (intellectual and academic) to be a bit higher.

I was not prepared for the lack of enthusiasm from some students in the university.

These emotions of frustration point to a lack of pre-knowledge before the teaching process begins, and the mismatch between an ideal of tertiary students and the reality of the work of the tutor (Gottschalk & McEachern, 2011). Others, however, reported that students were well motivated and required only little encouragement:

I thought students would be already enthusiastic about and motivated to learn a language: that has been the case.

My expectation of students' motivation at uni level was high and teaching at (University X) definitely has met my expectation.

I was expecting to find motivated students and I did find many of them!

Another issue concerns the expected workload. These comments indicate that not enough is being done for casual staff to prepare them for the amount of time that teaching is likely to take, and how teaching commitments can be managed alongside other priorities:

I don't think my contract accurately reflects the amount of work I do!

I knew there would be a lot of admin tasks to do: that is the case.

It turned out to be a lot harder than I thought.

I did not expect it to take so much of my time and energy.

They never allocate enough hours to properly mark a paper AND leave feedback/corrections.

These comments have serious implications for the quality of assessment and feedback which students receive, as well as the conditions of the casual members involved. This is an issue also raised by Grainger, Adie and Weir (2016) in their paper on quality assurance of assessment involving sessional staff. They report the comments from a teacher who noted that "I think many times tutors have not fully understood the Lecturer/Co-ordinator's expectations of the task or the criteria sheet" (p. 553). The authors go on to say that sessional staff identified that, "for assessment to be equitable, they needed to understand the coordinator's expectations and the purpose of the task so that this could be relayed to their students" (2016, pp. 553-54). The comments from our sample above also raise notions of equity and fairness, not just for the casual staff member and students, but clearly for the coordinators as well, who need to ensure that their own expectations are clearly articulated and understood by all parties.

The third issue concerned expectations of pay and conditions and the question of secure employment. In many cases, respondents were explicit about their expectation that teaching would lead to a permanent position, and how they have had to alter this perception. In at least one instance, the dashed expectation has not diminished the enjoyment from the activity itself:

I thought that I could eventually get a permanent teaching-only position: that, I think, is me dreaming…

When I consider how tenuous my position is I feel sometimes that I have perhaps wasted my time although it has been an enjoyable experience.

I just find the lack of job certainty really frustrating and stressful.

I thought that after teaching for a few years, with a PhD and research experience, a permanent position would have come up by now. This is not going to happen in the near future…

Matters are made worse, in turn, by the pay and conditions included in contracts themselves. Only one person seemed satisfied with the current pay rate for casual teaching, reporting that ‘the pay is excellent'. These comments hint at broader issues of casual work in general and the status surrounding temporary positions:

The biggest downside of all sessional teaching is the lack of respect from HR (…) I feel that universities now rely much more heavily on sessional teaching than before, but the status of the work remains low.

I have seen, however, incredible turnover in the time I have been at (University X), and am now only one of only three sessional staff members who has been there longer than 1 year.

I always have the feeling that my ideas and my knowledge about teaching are not important, and this is a pity (…) I think University (and staff) would benefit considerably from a better coordination of sessional staff.

The final question in our survey was designed to elicit broader questions regarding expectations and sessional employment in language departments. Given the degree of job insecurity that sessional staff face, it is somewhat unsurprising that almost all responses to this question concerned precisely this issue. The difficulties raised by these comments are not matters confined only to language teaching staff, but clearly affect the broader sessional workforce throughout Australian universities. The frustration that many respondents experience can be gauged by even a cursory glance at the language used throughout the comments: demoralising; anxious situation; vulnerable; undervalued; frustrating; disgusted; it sucks! etc. One exception to the overwhelmingly negative tone from the majority was the following comment, clearly from a person who was nearing retirement:

I've found it a very satisfying way to cap my long teaching career… and there's no sunset clause either.

What is most striking from these data is the resilient and positive attitude sessional staff have to the work itself. In other words, programmes and disciplines are not making effective use out of what is a highly qualified workforce, which has repercussions at the grass-roots level of teaching. It is disheartening that the knowledge and skills held by sessional staff are not being exercised more efficiently, especially if they are the ones who will ultimately perform the majority of teaching. What seems to be missed by university managers is that the skills of the staff (in which they have invested) are being wasted - they are, in essence, misusing their own resources. Further, there is a frustrated sector of the academic labour market which is considering abandoning the sector, or who are focusing on matters other than teaching quality, as shown in the comments below:

As a whole, I would say that teaching is undervalued in the university system, and as someone who loves teaching and who goes beyond the call of duty for my students, I am frustrated at how little the university places value on my skills, and have decided to take them elsewhere. There is so little professional development and accountability in the system, it's not funny.

I feel like my talents are being somewhat wasted as a casual.

I would like to get more appreciation for what I do. Permanent staff get promotions, scholarships, awards, etc. but there is nothing like that for us. Some of us have more experience and initiative than many of the permanent staff, and it would be nice if we were included in decision-making processes, too.

It seems university is not valuing sessional teachers, if it is true that a simplification of pay rates will mean a significantly lower pay. I also have to pay my bills, and I feel this kind of work is not allowing me to fulfill my potential. I wonder if universities do realise the importance of the work sessional teachers are making for them.

In general I have the experience that at the university level teaching does not get a very high profile and the fact that we are all trained educators in our program makes a big difference and results in very good student feedback.

Similar sentiments were expressed in Kimber's 2003 data, whose respondents reported "relatively high levels of dissatisfaction with their quality of working life" (2003, p. 47). This finding suggests that the issues raised in Kimber's paper, such as lack of control over hours worked, increased work-pace and workload, increased class size, lack of access to paid sick leave etc., have still not been adequately resolved. The implications arising out of this scenario are serious. Moves to counter the negative effects arising from casualisation in general can be seen from two opposing, but also complementary points of view. On the one hand, they point to a need for unions to campaign more vigorously for legislative changes to secure ongoing work for casual workers. In Australia, this push has already been signalled by the Australian Council of Trade Unions as a priority for 2018 (Knaus, 2017). In the university context, Hare (2016) has highlighted the implications which reliance on casual academic staff have for undermining the education experience of students. These include issues of accessibility to tutors by students outside of class hours, workload and ‘burn-out' for casual staff, issues of superannuation and the loss of a culture of ‘continuity' within degree programmes. These moves are, so to speak, a top-down or macro approach affecting the sector as a whole. On the other hand, certain universities have been proactive at a grass-roots level. Centres for Teaching & Learning, as well as informal meetings between casual staff, facilitate the sharing of ideas and strategies for teaching. Technology is helping to create online spaces for better communication. Nevertheless, the fundamental problems will persist as long as contracts remain short, and university managers continue to rely on casual staff on a semester-to-semester basis.

The point of this paper has been to provide an honest portrait of the issues which casuals are experiencing in one particular sector of Australian universities. The key finding that has emerged from this research so far is that, although most staff appear to be satisfied with the work itself, the peripheral issues which accompany a short-term contract are often unexpected, and are largely ignored by universities.

In providing a voice to the protagonists of this phenomenon, our aim has been to point out some of the most pressing issues experienced by casual staff and help to continue the debate. Another very important issue that the respondents to our survey have raised is the waste of academic qualifications, preparation, and enthusiasm of the people involved in casual teaching - people who could be a valuable resource in improving a tradition of quality in higher education. To be solved, this issue would require a drastic reexamination of the entire system, that is certainly far from the intentions and scope of this paper. However, the acknowledgment of this flaw should be one of the central concerns for further research (cf. Kezar, 2013).

This paper is one of few which deals with the issue of expectations and casualisation in contemporary universities. Further avenues of research will be able to build on the results presented here by looking further at how these expectations form, where they derive from and how universities can best prepare casual staff to provide a more realistic picture of the reality of teaching at a tertiary institution. Knowing what these expectations are is crucial in order to be able to provide a more satisfying outcome for both casual staff and students. Other research areas arising from this paper include how the intersections between unions and casual staff can support one another, how images of university employment are projected onto potential casual employees more generally, and how avenues of communication can be improved at the nexus between unit coordinators, casual staff and the university, thus leading to a more equitable educational outcome for all participants.

In their study on "countering juniorization and casualization" in the tertiary languages sector, Nettelbeck, Hajek and Woods (2012, p. 69) note that "endemic casualization is also a form of exploitation of the casuals themselves", and refer specifically to expectations when they write that "they [casuals] cannot be expected to participate - although to their immense credit, many do - in the intellectual life of their discipline". It is our hope that the opinions reported by casual staff in this paper help the sector to understand the difficulties of working as a sessional staff member in the contemporary Australian university. It is precisely by university administrators and those involved in the education system that these voices must be heard.

Josh Brown has recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship in Italian Studies at Stockholm University and is currently an Honorary Research Fellow at The University of Western Australia. His research focuses on casualisation in higher education, as well as how degree structures can positively affect language enrolments. He is working on several topics around these themes with colleagues in Sweden and Australia. Twitter: @giosuemarrone

Federica Verdina has recently finished a Ph.D. in Italian Studies at The University of Western Australia and teaches Italian language and culture at the same institution. Her research interests include the history of the Italian language and teaching and learning in language education. With a UWA research team, Federica is conducting a project on the optimisation of adaptive learning tools in higher education.

Andrews, S., Bare, L., Bentley, P., Goedegebuure, L., Pugsley, C. & Rance, B. (2016). Contingent academic employment in Australian universities. LH Martin Institute for Tertiary Education Leadership and Management. Retrieved from: https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/2564262/2016-contingent-academic-employment-in-australian-universities-updatedapr16.pdf

Berman, R. (2011). The Real Language Crisis. Retrieved from: http://www.aaup.org/article/real-language-crisis#.VWbvac-qqzB

Bexley, E., James, R., & Arkoudis, S. (2011). The Australian academic profession in transition. Commissioned report prepared for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Brown, J. D., & Rodgers, T. S. (2002). Doing second language research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bryson, C. (2013). Supporting sessional teaching staff in the UK - to what extent is there real progress? Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 10(3), 1-17.

Cahir, J., McNeill, M., Bosanquet, A., &

Jacenyik-Trawoger, C. (2014). Walking out the door: casualisation and

implementing Moodle. The International Journal of Education Management, 28(1),

5-14.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-06-2012-0076

Eagan, M. K. J., Jaeger, A. J., &

Grantham, A. (2015). Supporting the Academic Majority: Policies and

Practices Related to Part-Time Faculty's Job Satisfaction. The Journal of

Higher Education, 86(3), 448-483.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2015.0012

Ferrari, E., & Hajek, J. (2012). What place for sessionals in languages and cultures education in Australian universities? A first national report. In J. Hajek, C. Nettelbeck, & A. Woods (Eds.), The Next Step: Introducing the Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities (pp. 21-33). Sydney: Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education.

Gill, R. (2009). Breaking the silence: The hidden injuries of neo-liberal academia. In R. Flood & R. Gill (Eds.), Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process: Feminist Reflections (pp. 228-245). London: Routledge.

Gottschalk, L. & McEachern, S. (2011). The frustrated career: Casual employment in higher education. Australian Universities' Review, 52(1), 37-51.

Grainger, P., Adie, L., & Weir, K. (2016). Quality

assurance of assessment and moderation discourses involving sessional staff. Assessment

& Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(4), 548-559.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1030333

Hajek, J., Nettelbeck, C., & Woods, A. (2012). The Next Step: Introducing the Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities. Sydney: Office for Learning and Teaching.

Hare, J. (2016). Questions raised on impact of increased use of casual academics. Retrieved from https://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/questions-raised-on-impact-of-increased-use-of-casual-academics/news-story/a23f354e6adc6f5a814c4030503633e3.

Hil, R. (2012). Whackademia: an insider's account of the troubled university. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Kezar, A. (2013). Examining Non-tenure Track Faculty

Perceptions of How Departmental Policies and Practices Shape their Performance

and Ability to Create Student Learning at Four-Year Institutions. Research

in Higher Education, 54(5), 571-598.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9288-5

Kimber, M. (2003). The tenured "core" and the tenuous

"periphery": the casualisation of academic work in Australian universities. Journal

of Higher Education Policy and Management, 25(1), 41-50.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800305738

Knaus, C. (2017). Unions to fight casualisation of Australia's workforce. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/dec/27/unions-to-fight-casualisation-of-australias-workforce

Lane, B., & Hare, J. (2014). Demand drives increase in casual staff at universities. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/demand-drives-increase-in-casual-staff-at-universities/story-e6frgcjx-1226817950347

Leigh, J. (2014). "I Still Feel Isolated and Disposable":

Perceptions of Professional Development for Part-time Teachers in HE. Journal

of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 2(2), 10-16.

doi: https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v2i2.105

May, R. (2011). Casualisation: here to stay? The modern university and its divided workforce. In R. Markey (Ed.), Dialogue Downunder: Refereed Proceedings of the 25th Conference of AIRAANZA. Auckland: AIRAANZA.

May, R., Strachan, G., Broadbent, K., & Peetz, D. (2011). The Casual Approach to University Teaching: Time for a Re-Think? In K. Krause, M. Buckridge, C. Grimmer, & S. Purbrick-Illek (Eds.), Research and Development in Higher Education: Reshaping Higher Education, 34 (pp. 188-197). Milperra, New South Wales: Published by the Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia.

Nettelbeck, C., Hajek, J., & Woods, A. (2012). Leadership and development versus casualization of language professionals in Australian universities: Mapping the present for our future. In J. Hajek, C. Nettelbeck, & A. Woods (Eds.), The Next Step: Introducing the Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities. (pp. 35-46). Sydney: Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education.

Sheen, V. (2012). Labour in vain: casualisation presents a precarious future for workers. Retrieved 9 May, 2017 from https://theconversation.com/labour-in-vain-casualisation-presents-a-precarious-future-for-workers-8181

Warner, M. (2015). Learning My Lesson. London Review of Books, 37(6), 8-14.

Woods, A., Nettelbeck, C., & Hajek, J. (2011). An introduction to the Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities. Languages Victoria (Journal of the Modern Language Teachers' Association of Victoria), 15(2), 27-30.

Zacharias, N. T. (2012). Qualitative Research Methods for Second Language Education: A Coursebook. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

[1] This paper uses the terms casual and sessional interchangeably. Bryson (2013, p. 1) notes that "sessional teachers" is an Australian term, but that in North America they are often called "adjunct faculty". In the UK, "they are most frequently called ‘part-time teachers' - which does not distinguish them from lecturers on part-time contracts - a rather unhelpful confusion in this context".

[2] It should be kept in mind that almost half our respondents are enrolled in a PhD or MA, and there are restrictions with regard to part-time working hours if they hold a scholarship. These hours can vary, but are typically limited to eight hours per week.