Claire Stocks, University of Central Lancashire, UK

The development and support of PhD students who teach has been of interest to higher education institutions and academic developers in the UK for at least the last 18 years. Much of the work on supporting Graduate Teaching Assistants, or GTAs, (a phrase which I intend to refer specifically to PhD students who undertake a reasonable amount of teaching and who, for the most part, intend to pursue an academic career – as opposed to PhD students who perform a limited amount of teaching mainly for financial reasons) has focused on the most effective ways to prepare them for their teaching role. That work is generally based on the understanding that, when first faced with the task of teaching students, most GTAs are interested in developing ‘survival skills’ that will enable them to begin teaching with increased confidence and at least a basic arsenal of ‘hints and tips’ for supporting student learning. The majority of the literature around the preparation of GTAs has therefore described different approaches to this task of helping GTAs to feel prepared to face students in the context of being “defensive about their lack of knowledge and concerned about how they will face potentially difficult situations” (Sharpe, 2000, p. 135).

In this paper, I will outline a slightly different approach to GTA development which, while addressing some of the common concerns of GTAs, combines preparation for teaching with a greater emphasis on equipping these potential future academics with the tools and approaches to engage in continual professional learning (CPL). Therefore, rather than addressing the question ‘how do we prepare GTAs to teach?’, the approach taken focuses on the question, ‘how do we prepare GTAs to learn from their teaching, and to continue to develop their practice for themselves?’. This focus on the interrogation of, reflection on, and development of practice is not new, and has been at the forefront of efforts to rethink what effective academic development might look like for ten years or so. For instance, attempts to ensure that development initiatives support academic staff to become self-regulated and reflective practitioners have been the focus of many programmes where “the challenge is to gear the learning environment towards supported self-learning” (Trevitt & Perera, 2009, p. 353). The challenge for developers has been to “foster reflection […] in order to explore together how we might expand our ways of knowing, and rehearse the new language and conceptual skills that are needed” (Trevitt, 2008, p. 503). Such challenges have been addressed in various ways – through, for instance, (re)defining the role of the developer not as ‘expert’/teacher but as co-learner (see Trevitt & Pererra, 2008, p. 353), and assessment processes which utilise things like the reflective portfolio, patchwork text (Winter, 2003) or reflective journal, each of which is intended to support on-going reflective practice. All of these advancements have emerged as academic developers have increasingly come to understand the specific ways in which learning as a practitioner is inherently connected to everyday work. Nevertheless, and despite these developments, many academic development initiatives still rely on a large ‘workshop’ component, and getting academics to commit to longer-term, authentic reflective practice remains a challenge in many HEIs.

While there may be a growing recognition, then, that workshops may not be the most effective way to support the development of practice, they remain a staple of many GTA (and other, more advanced) development programmes. This is perhaps not surprising, given that “traditional learning relies on providing knowledge in the form of solutions that are already known by the teacher”, and that participants often expect this approach since it is a feature of the academic learning with which they are well acquainted (Stark, 2006, p. 24). However, advocates of academic work as professional practice see significant drawbacks to workshops, and criticise them for “tak[ing] academics out of their normal context of work and treat[ing] different aspects of academic work – research, teaching, administration – as separate” (Boud & Brew, 2013, p. 209). As Green, Hibbins, Houghton and Ruutz explain, “the professional learning literature has become increasingly critical of the kind of ‘traditional PD’ (professional development), which Houle (1980) first defined as that which is didactically delivered by an expert, in a transient, one-off event, divorced from practice”. (Green, Hibbins, Houghton & Ruutz, 2013, p. 248). Furthermore, participants themselves often complain that workshops are too divorced from the reality of their day-to-day practice (perhaps partly because participants themselves struggle to apply generic ideas to their own disciplinary contexts) and therefore impose a further burden on top of the teaching, research and administration that they are engaged in. In contrast, “Effective learning (at work) is now known to: be interactive and long term; involve multiple opportunities for cycles of engagement and reflection, and collaborative participation; create trusting relationships and ‘investigative cultures’; and pay particular attention to ‘proximity to practice’” (Green, Hibbins, Houghton & Ruutz, 2013, p. 249). The focus on continual professional learning and the development of practice described in this paper necessitates a pedagogy grounded in the principles of work-based and experiential learning.

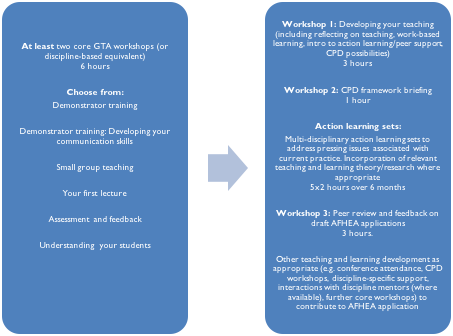

It is in this context of wishing to move away from the ‘traditional PD’ described by Green et. al. above that the support scheme for GTAs described in this paper was devised. Despite the criticisms levelled at workshops as a form of academic development, they can clearly be useful in certain circumstances. In particular, novice academics often report that even one-off workshops can be useful for combating isolation, normalising anxieties and allowing some space for thinking about teaching. For those PhD students who teach primarily to support themselves financially, who have very limited teaching responsibility and/or who have little intention of teaching in the future (or who plan to defer their real teaching development until they gain a lectureship) they may well provide enough support. However, for those GTAs who “see their teaching assistant role as an apprenticeship for lecturing and a way into the community of an academic department” it makes sense to participate in a programme which prepares them not just for teaching here and now, but for engaging in an on-going process of CPL (Sharpe, 2000, p. 133). The outline of the scheme is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Outline of the GTA scheme

The scheme provides two exit points: participants may just undertake one or more of the workshops outlined on the left of the diagram (institutional policy dictates that all PhD students who teach must undertake some training before they begin teaching), or they may choose to do at least two of the core workshops and then move to the second stage of the scheme. GTAs who wish to progress to the second stage of the scheme must be teaching regularly (at least two sessions a month), must have the support of their supervisory team, and must have official recognition of their teaching via a contract or letter of appointment (in line with university policy). The second stage shifts from a focus on teaching to a focus on developing teaching practice – through the use of action learning sets – and prepares them for making a claim for recognition by the UK’s Higher Education Academy at Associate Fellow level via the institution’s HEA-accredited CPD framework.

While workshops remain part of the second stage of the scheme, they are used to bookend the learning sets and orient students to the ways of working expected (including a brief rehearsal of action learning). The workshops brief participants about what is required in their claim for recognition, and allow peer review and feedback of written applications. The main bulk of the work in the second stage of the scheme is carried out in five, two-hour action learning sets which take place over six months, roughly six weeks apart, from October to March. Action learning essentially provides a support and structure to the process of learning from experience outlined by Kolb (1984), and encourages participants not only to reflect on challenges and issues that they have faced in their teaching, but also to make concrete changes to their practice in an effort to improve it. One aim of the learning sets, then, is to provide participants with a tried-and-tested approach to learning from their own experience of teaching. This process of interrogating one’s practice (or certain aspects of it) and implementing plans for improvement is therefore one that we would hope that participants can take forward as they gain more experience in, and responsibility for, teaching in their later careers. Each set is facilitated by a member of staff from the Educational Development Division, and has around 6-8 members from a range of disciplines. Each participant is expected to present a challenge or issue for discussion at least once, and other set members are briefed to help the presenter to explore his/her issue and to reach a point where s/he is committed to taking action. After the session, the institution’s e-learning environment provides participants with relevant reading and research connected with the issues discussed. In this way, the scholarship of learning and teaching is introduced in service of real issues when participants are most likely to be able to see connections with practice. At the next meeting, the presenter is expected to give a brief update outlining how the course of action adopted worked out in practice. This process is typical of an action learning approach which “is a continuous process of learning and reflection, supported by colleagues, with an intention of getting things done” (McGill & Beaty, 1999, p. 21).

The limited use of workshops alongside the action learning approach means that the educational developer is only in ‘teaching’ mode when setting participants’ expectations (in terms of the aims of the scheme and the roles that they are expected to play) and conveying information. The rest of the scheme is structured to be as democratic as possible in terms of contributions (to discussion and to giving feedback) and in determining directions explored and interests pursued. In this way, it is possible to provide timely support which explores the issues that are most pressing to participants, and allows for a very flexible curriculum which is responsive to participant needs. It is entirely plausible for each iteration of the scheme to cover quite different ground, depending on participant’s needs – in reality, however, the fact that GTAs tend to experience a number of core challenges means that the curriculum feels very flexible to participants while facilitators quickly become well-versed in the issues that tend to arise (albeit in slightly different guises). This is one of the strengths of the approach identified by Regan and Besemer (2009) in one of the very few articles discussing the uses of action learning in supporting GTAs: “a factor that strongly contributed to the success of ALGs was its problem-centred approach. Many PGRs had expressed annoyance at having to attend some of the generic skills training, which they perceived as having little relevance to their own learning needs. As the learning of the ALGs was entirely focused on issues that members themselves considered important, participants felt that the ALGs provided the kind of learning that was always relevant to them.” (Regan & Besemer, 2009, p. 215).

The action learning sets provide the participants with an opportunity to practice and develop a range of teaching-related transferable skills. In contrast to a workshop model where the facilitator is likely to lead discussion and where some participants may contribute in only limited ways, the action learning model provides a more democratic space for everyone to contribute. This allows participants to rehearse talking about teaching, from elaborating teaching challenges and explaining their context, to contributing to solving teaching problems and rehearsing their emerging pedagogic vocabulary. Participants also discuss teaching in a sustained way with peers from different departments and gain an understanding of how teaching is conducted in different disciplines – a valuable (and relatively rare) experience for those who may aspire to a teaching and learning leadership role in the future. As set members, participants are also encouraged to practice active listening, to give constructive feedback, and to formulate questions carefully to support the presenter’s learning, all of which are clearly useful in teaching and other interpersonal situations. In terms of their future teaching development, participants are also supported to establish clear, achievable and realistic goals, and to practice reflecting on and improving teaching. All of these benefits grow from the fact that the action learning sets require high levels of participation from members through “listening, observing, commenting and questioning the presenter” (McGill & Beatty, 1999, p. 59).

The action learning approach casts GTAs as engaged participants in the development of themselves and each other, and this also affords an opportunity “for experiencing positive agency [which is] critical in developing doctoral identity and a sense of academic belonging” (McAlpine & Asghar, 2010, p. 175-6). The fact that a set meets several times over a six-month period for fairly intensive discussion allows a cohort to develop; this not only goes some way to alleviating some of the sense of isolation that PhD students can feel, but also creates a space in which they can “compare themselves with others new to teaching and [find] that their problems [are] neither unique nor irresolvable” (Regan & Besemer, 2010, p. 214-5). The social nature of the learning supports the conceptualisation of the doctorate as a process of ‘becoming’ in which PhD students learn what it is to be an academic (teacher) through engagement in that role – it is only via this kind of experiential learning that doctoral students are able to really explore the complexities of academic work as it relates to them and their emerging academic identities.

The action learning approach, through which participants are supported to reflect, and ultimately to take action on, the challenges that they experience in their day-to-day practice provides a situation which supports the agency of the GTAs. Much has been made of the fact that neoliberalism has created an academic environment in which, particularly early career academics, may experience very limited ability to act agentically (see, for example, Archer, 2008). However, in his critical realist reading of agency, Peter Kahn points out that:

where reflexive deliberation is allowed to occur in relation to their own concerns, we suggest that participants are able to take a more active stance in shaping educational projects to ensure that connections are made with aspects of their practice […] An active stance is more likely to occur where insights for practice emerge from engaging in reflection and, indeed, where scope is present for practice to change as a result of such insight. Reflection should lead to the creation and application of resources for the development of practice. (Kahn, Qualter, & Young, 2012, pp. 865-6)

In the learning sets, participants bring their own concerns for discussion and are specifically supported to pursue changes in practice. In contexts where we are striving to support genuine reflection that leads to positive changes in practice, we must seek to ensure that the concerns of the developmental interventions that we use align very closely with those of the participants that we are working with. Action learning allows that alignment to happen naturally; concerns of the set are dictated by the members of the set (who very frequently come to realise that those concerns are generally shared by most, if not all, of the other set members).

In reflecting on their own experiences as Early Career Academics (ECAs) Monk and McKay explain that the support afforded by the community of practice that they developed has “provided a space to make sense of the institutional logic in which we develop and shape our identities. It has also afforded us a space where we can affirm our own and each other’s competencies” (Monk & McKay, 2017, p. 4). The learning sets (which can be seen as a kind of structured community of practice) allow participants to explore their place and agency within the disciplinary and institutional cultures that they find themselves in. While discussions in the action learning sets are ostensibly focused on fairly specific teaching issues, in practice, efforts to find appropriate resolutions often involve the exploration of the broader context in which the GTAs find themselves. For instance, a discussion in one of the sets about how long it takes to deliver effective, individualised feedback to students began to explore the extent to which students value and use feedback, the pressures on GTAs to complete their PhD within 3 years, the extent to which the department sees feedback as essential to supporting student learning and the GTA’s personal values around doing a good job as a teacher. In this way, the learning sets allow GTAs to examine how their practice within a department might be influenced by the broader institutional context that also affects their peers in other parts of the University. Furthermore, it also allows them to explore their teaching role in relation to their research role, something that can be discouraged by workshop programmes that focus primarily (or even solely) on teaching practice. The reality of academic work “involves confronting […] competing and sometimes contradictory demands”, and the learning sets allow the GTAs a space in which to begin identifying and responding to these complexities (Boud & Brew, 2013, p. 216). The sets thus provide some protected time and space for participants to do the critical reflection and development of agency that Monk and Mckay (2017) argue are essential for ECAs.

The constructivist and dialogic nature of the learning sets allows participants to explore ways in which new insights and knowledge about teaching makes sense to them in their context, and in relation to their practice. The purpose of a set member is “not to offer advice (although this has its place at times) but rather to help each individual to understand their situation better by exploration through reflection and to challenge assumptions underlying these reflections in order to decide the best course of action” (McGill & Beaty, 1999, p. 35). This approach, in which participants are in dialogue with peers, is fundamental to “facilitating reflection on practice” (Kahn, Qualter, & Young, 2012, p. 867). According to Kahn et. al., dialogue “allow[s] for the extended consideration of problematic aspects of practice, the voicing of experience and the views of others, the inclusion of challenges, prompts, questioning and crossing of boundaries, the use of specialist language and so on” (ibid). Furthermore, the sustained and comprehensive discussion of teaching challenges between peers from different parts of the University “can help one to adopt new perspectives on teaching and learning, as colleagues identify assumptions behind one’s practice or alternative viewpoints” (ibid). While talking through their issues, participants would often explicitly identify a change in their perception of the issue at hand, and would gratefully receive suggestions from other members of the set who had experience from very different disciplinary contexts. Members also noted that being asked challenging questions in a supportive space led them to reconsider practices or assumptions that they might have previously taken for granted.

So far I have argued that an action learning approach to GTA development has benefits for participants, particularly in terms of supporting them to develop their own agency and gain greater understanding of the sometimes ambiguous contexts in which they have to situate themselves and their practice. However, there are also benefits for educational developers in using an action learning approach. Some of the potential implications for the use of action learning – for the way that developers work and the roles that they occupy – have been explored elsewhere (see Stocks, Trevitt, & Hughes, 2018). Here, I would like to focus on the more practical benefits that might accrue when action learning is adopted not in support of workshops, but as the main mode of development.

The impact of developmental support can be notoriously difficult to evaluate, especially if we attempt to move beyond the ‘end of workshop’ questionnaire in an effort to ascertain whether our programmes have any effect on the practice of our participants. However, the structure of action learning, in which a presenter is required to commit to taking action and then report back on progress at a later meeting means that we do get some sense of how practice has been impacted by the reflections undertaken in the learning set. In some cases, it may be that the presenter decides to take no action in relation to the issue discussed, but s/he does so on the understanding that, as a result, little is likely to change in the situation. The presenter has also come to this conclusion decisively, having reflected on the situation at hand (rather than as a result of feeling powerless), and decided that taking no action is the best course open. Again, this is likely to increase feelings of agency as participants decide for themselves that what seemed like a concern is not actually worth pursuing after all.

One of the main challenges associated with moving away from workshop delivery is the scalability of alternatives. In theory, a workshop can be delivered to large numbers of participants at a time (although most developers have ideas about what the maximum number for an effective session might be). With an action learning set, numbers should probably be kept at fewer than 10 in order to enable high levels of participation, good quality discussion and a positive group atmosphere. In our programme we have run three sets of 7-8 participants for two hours at a time, and so they are reasonably resource-intensive. Nevertheless, I would argue that, for the reasons outlined above, the pay-off is worth the investment. While workshops have been criticised in the ways outlined above, action learning provides development leading to action and almost immediate changes to teaching practice in ways that workshops struggle to achieve (or that we struggle to measure). Furthermore, although the learning sets are an intense experience for the facilitator/developer (who must attend to process as well as content), the facilitator is not in ‘expert’ mode and is therefore not expected to offer knowledge or ready-made hints and tips. Rather, s/he is there to facilitate the discussion in a direction, which leads the presenter to develop concrete actions to take away. This means that set facilitators must be relatively experienced educational developers with a good, broad knowledge of the issues faced by GTAs in general and within the particular institutional context. On the other hand, the nature of the set meetings, where the issues to be raised are not known in advance, means that facilitators cannot prepare in advance for specific sessions - the great majority of the facilitator’s work is done in the set, with relatively little preparation (once the role of facilitator is understood) beforehand.

In our GTA development programme, the action learning sets were not in support of workshops, but were the main developmental intervention. However, as Figure 1 shows, workshops have been used in support of the learning sets. The workshops work well in terms of providing some general hints and tips for classroom management, but the learning sets allow developers to move beyond teaching about teaching, to supporting learning about teaching. In this sense, the GTAs are offered a model (based on Kolb, 1984) for their continual professional learning in their particular contexts, rather than generic solutions. In the sets, participants are encouraged to reflect, but also to gain feedback from colleagues, which helps to expose their personal assumptions and also the disciplinary habits, that they may take for granted. Stephen Brookfield makes the point that “we fall into the habits of justifying what we do by reference to unchecked ‘common sense’ and of thinking that the unconfirmed evidence of our own eyes is always accurate and valid. ‘Of course we know what's going on in our classrooms’ we say to ourselves, ‘after all, we've been doing this for years, haven’t we?’ Yet unexamined common sense is a notoriously unreliable guide to action.” (1995, p. 4). For Brookfield, critical reflection of the type supported by action learning is one way to ‘hunt assumptions’ and avoid the taken-for-granted.

Having completed the series of learning sets, participants are in a position to make a claim against dimension 1 of the UKPSF (Associate Fellow of the HEA) but, more importantly, they have also engaged in a process of developing their practice through discussion, reflection and engagement with the literature on learning and teaching in HE. The sets therefore provide them with a basis for the on-going development of their teaching practice, whether or not they have access to formal learning opportunities. This is where the sets really have the potential to contribute to the continuing professional development of the participants; through the sets, they have rehearsed a structured way to address teaching challenges that they have faced and found ways to adapt their practice in response.

Clearly, there are also challenges in using an action learning approach, both in terms of how participants engage (or not) and in terms of the role of an effective facilitator. For instance, not all participants are equally equipped to reflect critically on their practice, and they are not all necessarily keen to make changes to what they may already feel to be reasonably successful teaching. Where this is the case, action learning can be experienced as frustrating since, without a challenge to address, there is little point in the process. Some participants are not particularly good at democratic discussion or at asking questions to support other people’s learning (as opposed to trying to persuade others that their proposed solution is the best one). Here, the facilitator’s role is essential in helping the questioner to see that the point is not to offer solutions, but to ask questions that might support greater insight and help the presenter to learn from his/her experience. Again, it can be a frustrating process for a set member who believes that s/he has the solution to be told that the presenter needs to determine his/her own solution in order to maximise the chances of implementation. These issues can challenge the skills of the facilitator in ways that workshops don’t, but they also provide an opportunity for the development of the skills of both participants and the facilitator.

In conclusion, my experience of using action learning as a way to support GTAs to develop their teaching practice and to prepare to make a claim for professional recognition of their teaching has shown many benefits, particularly for this group of early career academics. Some of the benefits (particularly in relation to transferable skills development) were anticipated, and others have emerged as a result of experiencing and reflecting on the process. In particular, the potential for supporting the agency of a group who, it is often argued, have very limited opportunity to implement changes to practice, is quite powerful. Kahn argues that “early-career academics (if indeed they have taught at all before) engage in teaching on a relatively limited basis […] with the framework for teaching usually established by someone else” (Kahn, 2009, p. 197). Nevertheless, I would argue that involvement in action learning sets supports GTAs to develop agency in relation to their (perhaps limited) teaching role, and provides a structure for beginning to explore some of the wider disciplinary and institutional contexts that they are expected to practice in. Furthermore, action learning provides the GTAs with a model for reflecting and implementing improvements to their practice, which, we would hope, they can take forward as they develop their careers.

Dr. Claire Stocks is Academic Development Lead in the Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at the University of Central Lancashire. Her research interests are in the development of novice academics, using work-based learning approaches in academic development and, more recently, in autoethnographic approaches to understanding academic development practice. E-mail: CStocks3@uclan.ac.uk

Archer, L. (2008). Younger academics’ constructions of

‘authenticity’, ‘success’ and professional identity. Studies in Higher

Education, 33(4), 385-403.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802211729

Boud, D., & Brew, A. (2013). Reconceptualising academic

work as professional practice: implications for academic development. International

Journal for Academic Development, 18(3), 208-221.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.671771

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Green, W., Hibbins, R., Houghton, L., & Ruutz, A.

(2013). Reviving praxis: stories of continual professional learning and

practice architectures in a faculty-based teaching community of practice. Oxford

Review of Education, 39(2), 247-266.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.791266

Kahn, P. (2009). Contexts for teaching and the exercise of

agency in early-career academics: perspectives from realist social theory. International

Journal for Academic Development, 14(3), 197-207.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440903106510

Kahn, P., Qualter, A., & Young, R. (2012). Structure

and agency in learning: a critical realist theory of the development of

capacity to reflect on academic practice. Higher Education Research and

Development, 31(6), 859-871.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.656078

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. London: Prentice Hall.

McAlpine, L., & Asghar, A. (2010). Enhancing academic

climate: doctoral students as their own developers. International Journal

for Academic Development, 15(2), 167-178.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13601441003738392

McGill, I., & Beaty, L. (1999). Action Learning: a guide for professional, management & educational development. London: Kogan Page.

Monk, S., & McKay, L. (2017). Developing identity and

agency as an early career academic: lessons from Alice. International

Journal for Academic Development, 22(3).

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1306532

Regan, J., & Besemer, K. (2009). Using action learning

to support doctoral students to develop their teaching practice. International

Journal for Academic Development, 14(3), 209-220.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440903106536

Sharpe, R. (2000). A Framework for Training Graduate

Teaching Assistants. Teacher Development, 4(1), 131-143.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530000200106

Stark, S. (2006). Using action learning for professional

development. Educational Action Research, 14(1), 23-43.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790600585244

Stocks, C., Trevitt, C., & Hughes, J. (2018). Exploring

action learning for academic development in research intensive settings. Innovations

in Education and Teaching International.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1417886

Trevitt, C. (2008). Learning in academia is more than

academic learning: action research in academic practice for and with medical

academics. Educational Action Research, 16, 495-515.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802445676

Trevitt, C., & Perera, C. (2009). Self and continuing

professional learning (development): issues of curriculum and identity

in developing academic practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(4),

347-359.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903050095

Winter, R. (2003). Contextualizing the Patchwork Text:

addressing problems of coursework assessment in higher education, Innovations

in Education and Teaching International, 40(2), 112-122.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1470329031000088978