Linda Allin, Andy Coyles and Rick Hayman, Northumbria University, UK

All authors contributed equally to the paper and are considered co-first authors

The need for this study arose due to an issue with relatively high withdrawal rates across the first year of the sport degree programmes at our post 1992 institution in the North of England. The issue of retention is apparent across the higher education (HE) sector and is particularly concerning in the current climate, given both loss of income from an institutional perspective and the social responsibility of HE institutions to devise strategies to maximise the chances of a successful transition to university with an increasingly diverse student body (Thomas, 2012).

In examining this transition, it is widely recognised that the move from school or college to university involves a complex process of change, which some students manage more successfully than others (Richardson, King, Garrett, & Wrench, 2012). There is also growing evidence that social integration, as much as academic integration, is important to a successful transition (Berger, 1997; Braxton & McClendon, 2001; Tinto, 1987; Wilcox, Winn, & Fyvie-Gauld, 2005). In relation to social integration, the work of Tinto (1975; 1987) suggests the process of transition to college or university involves students moving from membership of previous communities to memberships of new communities. That is, students leave previous associations or activities behind and forge new friendships and social relations to become part of communities associated with their new environment. These may include communities associated with campus life, halls of residence, societies, sports and/or academic learning. A successful transition results in students feeling they have settled in to their course and university life with new friends and sense of belonging.

Thomas (2002) identified that a number of factors relating to social integration are influential in the decision to stay or withdraw from university in the first few months. These include homesickness and difficulties in making new friends (Mackie, 1998). These difficulties are exacerbated with the diversity of students now coming to university. For example, many students no longer leave home, but rather commute to local universities, which may make the separation from home to university increasingly blurred. In support of this, Berger (1997) found students who did not live in student accommodation were more likely to feel marginalised, with friendships in halls of residences important sources of a sense of community. Students from working class backgrounds (Rubin, 2012) and non-traditional students (e.g. mature or part time students) also find it more difficult in making the transition and have higher attrition rates (Tinto, 2010). A further study by Wilcox et al. (2005) focused specifically on one aspect of social integration, namely social support, to examine the process through which social integration influenced student withdrawal decisions. They suggested maintaining social support with peers and with staff were highly important for a positive student experience. In university systems the personal tutor may therefore also be part of a student’s social support network, as can peer mentoring (Heirdsfield, Walker, & Walsh, 2008).

Sport is also central to the lives of many students who come to university, particularly for those choosing to study sports programmes. We suggest that making new friends and communities through sport participation may therefore be an additional factor in positively influencing social integration. The role of sport in supporting students’ social integration in the first year of university, however, has to date been under-researched. This is surprising, given the support at the national and international level for the role of sport in social and community development (Sport England, 2017). There is also evidence that retention and withdrawal rates are different across disciplines (Woodfield, 2014). However, sport can also potentially be exclusive, with competition for university teams and difficulties in access. We suggest exploring the extent to which both formal and informal opportunities for sport impact on the social integration experiences of sports students can give additional insights to our understanding of the first year transition. This may consequently help universities find ways to harness the potential value of sport participation to support this process. This study therefore aimed to understand how first year undergraduate sports students experience the process of social integration and the facilitators or barriers to their integration, with a view to improving our retention strategies. It further aimed to understand the role that sport may play in this transition process in order to offer a new avenue of research and ideas for practice.

This paper presents the qualitative component of an institutionally funded mixed methods project focusing on student retention. Specifically, it focuses on the findings from semi-structured interviews, which captured rich and insightful experiences of transition from ‘not yet settled’ students as identified through an initial student survey undertaken in the first week of the semester. As part of the design, four second year peer mentors, male and female, were recruited to work alongside the research team and conduct the interviews with students. A training session for peer mentors took place prior to interviews to help them in carrying out the interview process and in defining their roles and boundaries.

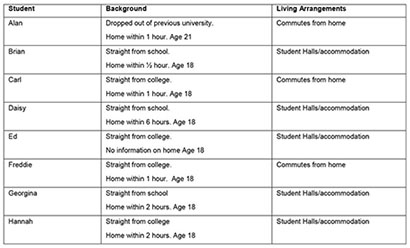

Student peer mentors undertook interviews with nine first year students (three females and six males) who were all over 18 years of age and enrolled on a sport degree programme. The research project gained ethical clearance and all participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. Details for each participant are provided below (pseudonyms are used to protect identity).

Table 1: Participant details

The primary aim of the semi-structured interviews was to gain further understanding and insight into the challenges, barriers, processes and facilitators encountered by first year sports students to achieving social integration. The interview commenced with open-ended questions focusing on participants’ further education, plus early experiences and expectations of transitioning to university. Latter stages focused on students’ perceived importance of social integration and concluded by discussing the role sport may play in supporting this process. To elicit greater richness and meaning to responses, questions when necessary, were supplemented by probes (Smith & Osborn, 2003). This enabled the direction of interviews to be guided by participants, rather than dictated by the schedule, and made it possible to follow up any additional information discussed (Smith, 1995). A copy of the interview guide is available on request from the research team.

All interviews took place at a convenient location and time for all students during November and December 2016. First year students were provided with the option to self-record their answers, be interviewed by a trained second year peer mentor, or be interviewed by a member of the research team with experience of undertaking qualitative pedagogic research. In all cases, the interviews took place with a peer mentor. Byrne, Brugha, Clarke, Lavelle and McGarvey (2015) suggest the use of peer interviewing tends to generate more open and honest discussions on sensitive topics. Consequently, it was felt this both encouraged and involved the second year peer mentors, and also enabled first year students to talk more freely about their experiences. Subsequent informal conversations with peer mentors suggested they found the process worthwhile and that it supported the development of their own research skills. Interviews were held within the grounds of the University Campus and lasted between 16 and 30 minutes.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and subjected to thematic analysis by each research team member. Every transcript was read independently on several occasions, with notes reflecting interesting and significant comments and meanings in relation to student responses placed within margins. Initial associations and connections based on similarities between emergent themes were made, resulting in the identification of key themes. Once these theme categories were agreed, interview extracts representing each theme were selected. The final analysis stage involved the research team collectively developing a written account from these themes. This account was reviewed and rewritten several times until the final version was agreed.

All those interviewed were still present at university at the time of interview and by this time expressed that they were enjoying it. As such, we argue that these interviewees were now in the process of a successful transition and had made new communities of friends (Tinto, 1987). The majority of students interviewed felt university was different from school or college, and expressed this difference mainly in terms of the increased independence, the making of new friends and the increased academic expectations. In particular, they talked of the challenges in finding lecture rooms, getting to grips with academic work, cooking or fending for themselves, and being in control of their own finances. It was also clear that on arrival, many of the students had concerns or anxieties in relation to the academic aspects that were new (e.g. referencing, essay writing and workload) and the meeting of new people. Freddie explained: “it is quite challenging in terms of the work, it’s a lot harder than you think, coming out of college”, whilst Carl admitted: “I didn’t realise how hard it was going to be at making mates”. Ed further identified that he had initially struggled socially by stating: “I didn’t get on with people at first”. For Islay, fears prior to attending university almost caused her not to arrive at all. She explained, “I was so scared to come here before because I was so nervous. I wasn’t even going to turn up to be honest”. Such feelings seem to be as eased for some students with recognition that others they met were in similar position. As Georgina indicated: “everyone is in the same situation so everyone’s like missing home and having to look after themselves”.

For those in student accommodation, the flats or halls of residence were important sources of social life, supporting the academic literature (Berger, 1997). Being able to get on with flatmates, going to different places with them and getting to know the surrounding area were helpful in building relationships. Daisy, for example, explained how meeting her flatmates was a key moment in her feeling a sense of belonging. She stated: “I think meeting my flatmates has been the highlight so far. Obviously they have been there from the beginning. They are my best friends to date”. Friends in accommodation were important for support in terms of homesickness, as Georgina suggested: “everyone [in the flat] looking after each other”. Not all students interviewed were in student accommodation, however, and not all identified accommodation as the most important aspect. Alan, for example, was a local mature student who had taken a year out after withdrawing from a previous course elsewhere. He did have halls, but said he preferred to go home, because he lived close, identifying a lack of communal living space in the hall accommodation. Carl, who also commuted, noted that not being in university accommodation made it harder for him to join in when initial friendships were extended and reinforced through social media. He explained:

I think accommodation plays like a big part in it, because everyone’s got like all these group chats and stuff… like I’m not in none of that, you know what I mean, so it’s kind of like they’re all using social media to talk and that and they’re like building their relationships whereas I’m not included in that type of thing […] everyone’s got a chat like ‘oh [name of student hall] and stuff’ (Carl)

Georgina confirmed this, noting “we’re always texting each other like oh are you in the flat”. Whilst halls and accommodation can be crucial areas of community development, it is therefore important to recognise that for students who commute, it may be important to find other ways in which they can be included in relationship building. It is also important to recognise the role social media and technology now plays in developing such early relations into longer-term friendships.

For first year students, nearly all universities have an induction week including programme specific activities to support social development. More than half of those interviewed (Brian, Hannah, Daisy, Islay and Alan) identified such induction week activities in helping them to make friends. Several highlighted when they were invited as a group to attend the local football stadium for a talk around community sport opportunities. Islay cited the informal atmosphere, arranged quiz and the opportunity to meet more people as a time when she met her now closest friend. She stated “when I went [to the stadium] I got to meet this girl. She is in my class now and we are really good friends”. This may have been because, as Brian noted, “it was a bit more relaxed and something different”.

Meeting academic and personal tutors was also an important part. Students highlighted the value of their personal tutors in terms of being approachable, feeling you could talk to them, being able to offer advice, direction and making them feel equal, but at the same time encouraging ownership and responsibility. This supports the finding of the What Works? Student Retention and Success publication (Thomas, 2012) in that feeling respected or valued can increase sense of integration. Where a particular tutor was perceived as less open or less approachable, this was identified as more problematic. Tutors were also key in supporting students to make friends. Freddie, who lived locally and commuted from home, suggested that “when I first got here there was a lecturer who basically said ‘if you don’t mix with people there is no point being here because you’re going to be isolated and you’re not going to enjoy university life’ which I took on board and thought I might as well get to know people”. Freddie could easily have remained with previous friendship groups. He explained that the direction from his tutor, with additional support “no need to stress, just relax”, influenced him in making the most of his transition. This resonates with findings of Wilcox et al., (2005) in highlighting the importance of support from staff in a positive student experience.

As students began classes, they highlighted how teaching style and delivery helped or hindered in meeting new people. It was clear that some tutors deliberately sought to mix students in seminar groups, actively involving them into group or problem solving activities and ensuring they sat with different groups of peers. Brian identified “they match you up in terms of […] when you first came they didn’t want you sitting next to someone you knew, […] they tried to get everyone as quickly as possibly integrated […] they sort of mixed groups up”. Hannah agreed and stated “they like you being in different groups […] a couple of lecturers here have taught people in our class who like joined games and that, to get them socially integrated”. Daisy’ stated “they [staff] kind of force you into it”.

As a sport cohort, practical coaching sessions and a ‘Streetgames’ module embedded in the first semester were further highlighted as helpful in getting to know classmates. For example, when asked what activities had helped him integrate the most, Carl explained “probably the Streetgames to be honest, where we’re all […] we have to like coach each other, or even just the sport coaching, like session because you have to coach so you just build respect off that”.

Seminar group activities, over lectures or classes that were less interactive, were a basis for friendships to grow. Such friendships often spilled over outside where particular seminar groups would go on activities or meet up outside class. Whilst positive, this could potentially also cause divisions. For example, Ed noted “like my seminar group doesn’t talk to the other one” but that he had initially made friends with peers in a different seminar group. He elaborated “it’s quite weird because I’m with my seminar group most times unless I am with the other seminar group outside uni”. In hindsight, Ed suggested that he felt he should have developed more friends within his seminar group. However, the potential separation of seminar groups, in terms of friendships, is something perhaps tutors or timetabling processes should be aware of, with potential for a lack of cohesion across a cohort. The gender balance within a seminar was also something to consider in making students feel comfortable. To illustrate, Daisy stated “we’re all really close but there’s’ only three of us girls and then the rest are boys […] so it’s very banterous”.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, sport was extremely important to the identities of the students interviewed. Examples suggesting sport was central to their identities included “part of my life most days” (Ed) “massive, it’s my life” (Hannah) “really important” (Daisy), “all I really do is play sport” (Freddie) “massive” (Carl) and “if there is not sport in my life it would be pretty boring” (Alan). In terms of social integration, their involvement in sport was a valuable way of initiating conversations and feeling as if they had something in common with other students.

yeah because it’s you’ve got something to talk about like you have stuff in common with other people so there’s a few of the lads who play rugby groups so I think it’s been very positive like integrating a group of sports. So you’re able you’re able to talk about a thing in common so you talk about rugby or football (Ed)

This sense of commonality helped students feel a sense of relatedness and eased their transition. As such, this was also used by some tutors as a way to involve students in groups within class. This significant student connection to sport, however, may potentially be untapped in considering the social integration process. Coming to university seemed to mark a change for some students in the role and place of sport in their lives. Whilst several of the students interviewed attempted to join university teams, others either decided not to participate in sporting trials in their previous activity or kept on with their sporting activity at home, as the opportunity to continue their sport was not available. Several students also felt intimidated or not good enough to try out for the university teams, and a couple of students had experienced injuries. For those who did or wanted to try out for teams, this led to feelings of being left out, disappointed or dissatisfied. The following quotes capture the essence of such experiences:

There were hundreds of lads there, and […] you could just have a bad day you know what I mean and you’re not in the team […] I was just thinking what’s the point? (Alan)

I did want to try out [for the team] but I just got a bit scared (Daisy)

I had to try out for a cheerleading team and I couldn’t get in because I wasn’t that good...there should be something like for just participating. It shouldn’t be like just a performance bit […] we’re feeling a bit left out’ (Islay)

I was going to try for swimming, just like to do for fun, but they only did obviously competitive swimming and I hadn’t swum in ages, I didn’t want to swim competitive. (Hannah)

Given the importance of sport to these students, this finding is disturbing. They suggest that whilst going to a university with a high sporting reputation is attractive, individual fears, perceived competence and a focus on performance sport in institutions may lead to dissatisfaction by students and contribute to feeling a lack of integration into the sporting life of the university. Some students made a conscious decision not to try out for sport team selection and try alternative activities such as the “dance society” to make friends, whilst Carl highlighted the importance of sport now for him in terms of fitness and health. Brian suggested he wouldn’t mind trying “something different such as ultimate frisbee”, but it seemed that on analysis, most interviewed students were either playing less sport or searching for other ways to be involved in student life, including volunteering. For those who did get in teams, going out and socializing with fellow squad members meant there was “always something to do on a Wednesday”. For those who did not, this potentially left an isolating gap. When asked how to improve, several students identified that they would have liked more social events such as sporting activities or activities in the larger gaps between timetabled lectures on a regular basis.

For the students in this study, both academic and social integration were highly important for sense of belonging and successful transition. The areas of accommodation, staff, curriculum activities and sporting opportunities emerged as key areas which specifically helped or hindered social integration. In the light of these findings, we propose the following suggestions for retention strategies. Many of these support both previous literature and good practice in developing student sense of belonging and engagement (Thomas, 2012). The role of sport is highlighted as an area of opportunity that can be harnessed for sport students, but may also be applicable in the wider student community.

Student halls and accommodation are important locations for making lasting and supportive friendships. Many universities now set up social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter where prospective students are able to seek out and develop connections with potential flatmates prior to their arrival. It is important to recognise the role social media now plays in reinforcing accommodation identities and to identify ways for those who commute and do not live in halls to build lasting relationships and new communities if we are to reduce the potential marginalisation of students who commute (Berger, 1997). This could be through constructing programme social network sites or encouraging the use of group chats around other areas.

Deliberate strategies to integrate students in seminars are important opportunities for developing new friends. Tutors also play a significant role through the types of activities they offer, the guidance and direction they give, their approachability and the interactions they have with students. This can make students feel valued, understood and part of university life. Tutors need to be made explicitly aware of this as a key part of their role in the first semester and guidance or training provided.

Sport is central to sport students’ sense of identity (and this may be so for other students) and can be a prime source of social integration (Sport England, 2017). It is vital that initial experiences of sport at university are positive and inclusive, with opportunities for participation easily accessible and ‘trials’ less intimidating and more encouraging. Opportunities need to be signposted for those who do not ‘make it’. New or fun activities are likely perceived as more important than competition. Social events or activities can be built into or around the curriculum, particularly using the ‘gaps between lectures where students may not make best use of their time.

Dr Linda Allin is an Associate Professor at Northumbria University. With over 20 years of experience in Higher Education, she is responsible for teaching excellence and enhancement in the Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and has undertaken several pedagogic projects relating student and staff collaboration.

Andy Coyles is a Senior Lecturer within the Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation at Northumbria University with several years of experience teaching in Higher Education. Furthermore, he has 12 years high performance coaching experience at two Premier League football academies.

Dr Rick Hayman is a Senior Lecturer within the Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation at Northumbria University and Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. With over ten years’ experience within Higher Education, he is passionate about teaching using innovative approaches that inspires students and colleagues.