Patricia A. Logan1,

David van Reyk2, Amy Johnston3, Elspeth Hillman4,

Jennifer L. Cox1,

Judith Salvage-Jones1, Judith Anderson1,

1Charles Sturt University, Australia

2University of Technology Sydney, Australia

3Griffith University & Gold Coast Health, Australia

4James Cook University, QLD, Australia

Student attrition in tertiary education remains a significant educational and financial burden on tertiary institutions. Maximising student retention is increasingly becoming a core responsibility of academic establishments. While most attention is focused on students in the first year of their programs (Kift, Nelson, & Clarke, 2010), there is increased interest in students entering via non-traditional routes including those using advanced standing for program entry.

Undergraduate nursing programs are no exception to these tertiary retention foci. Australia has a three level nursing education/qualification system enabling registration with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) – Enrolled Nurse (EN), Registered Nurse (RN) and Nurse Practitioner (NP). The level EN was introduced in the 1960s originally as a certificate qualification and because ENs were “considered faster to train, cheaper to employ and available in geographical areas (particularly rural) where there are shortages of RNs” (Jacob, McKenna & D’Amore, 2014, p. 648). A national training package was introduced in 2007 and since 2013, the national curriculum has led to a vocational education and training (VET) diploma. ENs with this diploma are given advanced standing enabling direct entry to year 2 tertiary pre-registration nursing programs. The progression from level 1 bioscience to level 2 pathophysiology and pharmacology courses has been recognised as challenging for all nursing students, evidenced by the presence of a second year slump in achieved grades (Logan, Dunphy, McClean, & Ireland, 2013). Typically, advanced standing includes first year bioscience subjects, yet ENs themselves indicate that their prior bioscience knowledge was insufficient to prepare them for university science (Hylton, 2005; Northall, Ramjan, Everett, & Salamonson, 2016) so the transition knowledge gap is even wider for these students.

VET transition students have been recognised as the “hidden disadvantaged” (Brunken & Delly, 2011, p. 143) often lacking the broad underpinning theoretical and critical components that are characteristic of tertiary study success (Catterall & Davis, 2012). Despite the apparent universality of VET EN programs, university educators indicate a vast difference in relative academic and theoretical preparedness of these students (Jacob et al., 2014). Adding to this disadvantage are the stresses of a new environment, conflicts between personal goals and family responsibilities, issues of developing a new student identity, alienation from EN colleagues, short-term financial losses and an unexpected level of academic workload (Towers, Cooke, Watson, Buys & Wilson, 2015; Ralph, Birks, Chapman, Muldoon & McPherson, 2013; Shea, Lysaght & Tanner, 2012) all of which can impact on student self-efficacy (Cox & Crane, 2014). Advanced standing also leads to the bypassing of first year university orientation programs further increasing the challenges for these students (Hutchinson, Mitchell, & John, 2011).

The responsibilities of the EN vary dramatically between health facilities, often with a substantial degree of overlap with those of RNs (Ralph et al., 2013). Without higher qualifications the career opportunities and progression for ENs are however, limited compared to those of RNs and thus, undertaking further study through enrolment in a BN program remains an attractive option. Such programs are often referred to as ‘conversion’ programs to distinguish them from standard university entry score programs. Preparatory programs in Australia dedicated to EN conversion students have been few in number and most were instigated prior to the implementation of the diploma for EN. In 2014, Logan and Cox developed a pilot preparatory program that included a website of resources to support EN transition (Logan & Cox, 2015). The success of the pilot led to the gathering of a team of academics to refine the program and develop an open access website. This paper presents the case study which provides the culmination of information that supports the website framework.

Case studies are a mechanism for detailed examination of a phenomenon which enables increased richness and depth of data associated with evolution over time that constitute the case as a whole. A case study can encompass the factors impacting on the phenomenon inclusive of the outliers or diversities surrounding the phenomenon (Flyvbjerg, 2011; Timmons & Cairns, 2012) allowing it to be viewed through more than one lens (Baxter & Jack, 2008). By bringing different forms of information together for analysis the case study provides a nuanced view of reality and consequently, enables the researcher to develop a higher level of expertise (Flyvbjerg, 2011) and provide a practical framework for generalisations or theoretical explications (Aaltio & Heilmann, 2012). In this way a case study can act as both a research methodology and method as well as a teaching method for the development of expertise (Flyvbjerg, 2011) and learning (Aaltio & Heilmann, 2012). This common-sense and flexible approach highlights the bringing together of complimentary information providing the foundations of the inner workings of a phenomenon that enables the testing of propositions (Aaltio & Heilmann, 2012; Flyvbjerg, 2011; Timmons & Cairns, 2012).

Qualitative descriptive case studies follow a constructivist premise inclusive of contextual conditions and narrative elements, with the phenomenon bounded by the context and the proposition. Multiple facets of a phenomenon can be revealed and understood providing the potential for theory generation (Baxter & Jack, 2008). Additionally, the delving into the ‘case’ can develop sensitivity to the issues at hand (Flyvbjerg, 2011). This case study looks to raise awareness of the experiences of the EN as they transition to university study enabling development of a strategy to assist this transition.

Provision of an open access resource will assist Enrolled Nurses (EN) with transition to university study and support revision of first year bioscience in order to promote success in pathophysiology, pharmacology and final year nursing curricula.

For this case study the context is the transition of ENs to university to complete a pre-registration nursing degree. The binding proposition (the equivalent of a hypothesis) is that provision of an open access website containing transition support materials will enable more successful transition and help limit attrition and slowed progressions. Hence this research paper collates data that supports the choices of inclusions for a website tailored to support the needs of the EN. The datasets include:

1. A summary of the peer-reviewed literature that develops our understanding of the challenges for EN undertaking transition

2. Content analysis of published interviews with three enrolled nurses who have or are undertaking pre-registration nursing study and finally,

3. A summary of the evaluation of the pilot website created within Charles Sturt University.

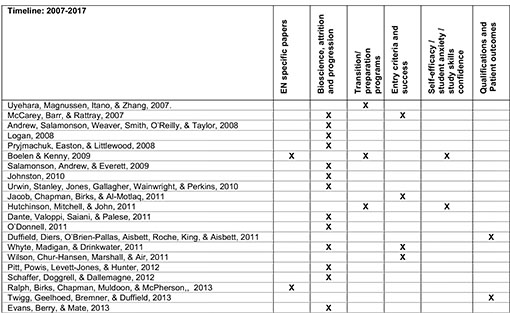

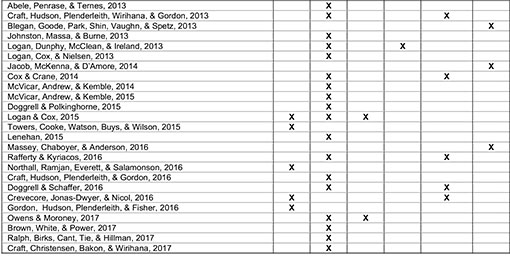

Table 1 provides a concise, sequential, summary of the many studies published since 2007 that have investigated factors impacting on nursing students’ attrition and progression throughout their undergraduate studies.

Three comprehensive reviews of nursing education and success factors with respect to bioscience have been undertaken. McVicar, Andrew and Kemble (2015) reviewed 19 studies in their integrative review and noted that few studies have undertaken systematic examination and tracking of level 1 bioscience scores despite more than 20 years of research into the ‘bioscience problem’. Pitt, Powis, Levett-Jones and Hunter (2012) reviewed 44 studies but only four of these overlapped with those in the McVicar et al. review, and Dante and colleagues (2011) who reviewed only five studies (Dante, Valoppi, Saiani & Palese, 2011). Pre-admission academic achievement, age and prior work in a health-related industry were inconsistent factors for success (Johnston, Massa & Burne, 2013; Johnston, 2010; Pitt et al., 2012; Dante et al., 2011; McVicar et al., 2015). Logan, Cox and Nielsen (2013) undertook a local review focusing on rural/regional campuses with nursing and paramedic students that did include level 1 bioscience results (n= 963). The results of this study, echoing other single study papers, showed that the mix of prior science study and the level of that study, as well as the responsibility level of prior health care work, were influential to success in bioscience.

Course organisation and delivery mode have been consistently linked to student success, as has inclusion of theory-practice links but local contexts influence these results (McVicar et al., 2015). It has not been clearly determined whether clinical practice reinforces science understanding (McVicar et al., 2015) or whether practical aspects of clinical practice reinforces the learning of clinical schemas without necessarily imparting the underlying theory (Logan, 2008). As Barradell (2013) notes, foundational concepts are used and integrated into clinical practice in different discipline-specific ways by the various health professions often resulting in practitioners being unable to articulate the foundational science supporting their practice. McVicar et al. (2015) also raise the question of whether bioscience modules lack application content in the first instance or if the students who report practice as key to their learning had initially failed to grasp the fundamentals in order to achieve applied understanding.

Relevance to practice has been repeatedly raised as a mechanism to support bioscience learning. Craft and colleagues (Craft, Hudson, Plenderleith, & Gordon, 2016), asked nursing students how they ranked the importance of secondary school science to success in tertiary studies. The findings indicated that work as an EN did not influence their perceptions of the importance of bioscience in undertaking their role as an RN. This was in contrast to those who had completed year 12 secondary science. In fact, a study by Chemers, Hu and Garcia (2001) found that nursing students viewed science as ‘something to be survived’ rather than as useful to practice although the interview data reviewed here (see Table 2) would indicate that this is not unanimous amongst ENs of more recent years. Thornton (1997) indicated that nurses’ perceptions of content relevance were related to their images of what nurses ‘need to know’ despite a number of older studies that demonstrate the impact of foundational bioscience upon practice (Casey, 1996; Jordan & Hughes, 1998; Prowse & Lyne, 2000). Success in the biosciences have a long history of linkages to academic success in nursing (Wong & Wong, 1999; Uyehara, Magnussen, Itano, & Zhang, 2007; Pitt et al., 2012; Brown, White, & Power, 2017; Massey, Chaboyer, & Anderson, 2016) with a study by Abele, Penrase and Ternes, (2013) finding that for every subject failed the probability of degree completion dropped by one third.

Table 1: Peer reviewed papers related to nursing student progression and attrition

The McVicar et al. (2015) study highlighted that students who were critical of bioscience content were also often critical of their teachers which potentially reflects the students’ anxieties in struggling with foundational bioscience. Cox and Crane (2014) undertook a study to determine levels of anxiety related to science study, termed ‘science anxiety’, in a cohort of new, year 1, nursing bioscience university students. Their study indicated that the level of frustration felt by students influenced their understanding of the importance of science in quality nursing practice. Further, this frustration, coupled with a lack of confidence in their ability to learn the material, reduced their self-efficacy (SE). These authors noted several studies supporting the premise that general anxiety was a predictor of science anxiety. A number of studies have indicated that SE is a positive predictor of academic performance (Chemers et al., 2001; Choi, 2005; Margolis & McCabe, 2006) and Andrew (1998) showed that SE ratings by nursing students were predictors of bioscience examination grades. Students who perform poorly often credit this to factors beyond their control or to a lack of intelligence (Cox & Crane, 2014). Those with low SE tend to over-estimate task difficulty (Cox & Crane, 2014), with poor SE beliefs ultimately becoming ‘self-fulfilling prophecies’ that impact negatively on psychological well-being and manifest in behavioural changes that not only result in poor assessment attempts but are often disruptive to classmates (Margolis & McCabe, 2006). Nursing students have consistently indicated that science content is a source of stress (Andrew et al., 2008; Craft et al., 2013; Cox & Crane, 2014; Craft et al., 2016).

Doggrell and Schaffer (2016) undertook a study to test memory recall over a period of 16 months with students enrolled in consecutive bioscience courses. They found that microbiology knowledge at initial testing was poor and that recall of this material did not improve despite prompts about repeated testing (the same test was used each time). They also tested gastrointestinal knowledge without giving students prior warning about test times. This knowledge decreased by 55% over time and raises the question of whether nursing students entering their final year, where complex care studies are undertaken, are fully engaging with their clinical studies and earlier course content. Indeed, ENs indicate a lack of confidence with memory and recall skills, learning new terminology, and reading skills for unfamiliar language (Craft et al., 2016). Thus working as an EN may not confer an understanding of the biomedical language required to fully participate in the medical discussions pertaining to the clinical environment.

Students with high test-anxiety have been shown to be those with poor study skills and study habits and less effective capacities for techniques such as memorisation (Cox & Crane, 2014). This can however be addressed academically. Lenehan (2015) undertook a study comparing the results of a group of nursing students who had been taught how to maximise their learning styles with a group of nursing students who had not. It was found it did make a significant difference to the students’ grade point average (n=103). There could be many confounders in a study this small and a number of studies rebut the usefulness of learning style categorisation (Kirschner & van Merrienboer, 2013) but the additive effect of building study skill capacity with many techniques for learning could be expected to reduce study anxiety and improve SE. Andrew’s PhD project (2002) indicated that nurses’ self-identified as needing more diverse study skill techniques to succeed in bioscience than they did for other nursing subjects. The cognitive dissonance that can result from expectations of study levels not being cognisant with reality can provide a strong impetus for leaving the university (O’Donnell, 2011).

A small number of bridging activities to aid EN transition have been reported and they have been shown to have a positive effect (Ralph et al., 2013; Laming & Kelly, 2013). One of the most recent compared three approaches: a two-day bioscience workshop (n=63); an online learning program (n= 263); and, a human body study club (n= 44). The last of these had the most effect on final grades while the workshop had no appreciable impact (Owens & Moroney, 2017). The online program did impact results, just not as impressively as did the study club (Owens & Moroney, 2017). Previously, Boelen and Kenny (2009) evaluated a compulsory transition program operating at LaTrobe University. In their study they reported that 87% of attendees indicated their confidence had improved as a result of the program. Griffith University’s program demonstrated a similar improvement in confidence (Hutchinson et al., 2011). These studies are in contrast to the results of Owens and Moroney (2017), but this may be due to the length of time dedicated to the workshop preparation program.

At Queensland University of Technology (QUT) attrition for ENs has approached 30% (Schaffer, Doggrell & Dallemagne, 2012; Doggrell & Polkinghorne, 2015). At Charles Sturt University’s regional campuses and in the distance programs, student persistence, regardless of poor progression limits attrition, providing evidence of student desire to progress their careers in rural and regional Australia. Wilson, Chur-Hansen, Marshall and Air (2014) noted that the hardships of study included financial stress, family commitments, and in many cases, due to being the first member of their immediate family to attend university, a lack of peer guidance and academic capital. Yet findings from the Ralph et al. study (2013) show these students feel undertaking higher study is worthwhile once they have graduated as an RN.

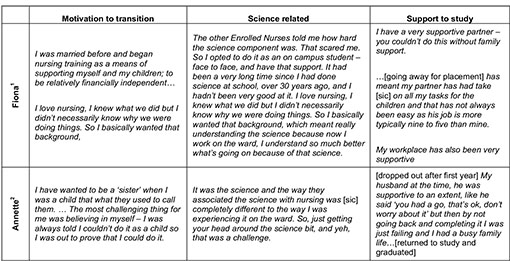

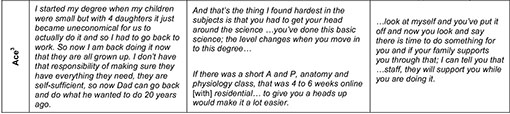

A search and review of published interviews with ENs revealed three: One as a full published transcript (in Cox, Logan, & Curtis, 2014), and two other video interviews included on the FirstDegree public website designed to help students understand university expectations. Analysis of the content of these interviews revealed three main themes: strong motivation to transition; support is paramount; and, science-related anxiety – ‘getting your head around the science’, are common. These themes are evident in the published literature and the results in keeping with the findings of larger studies undertaken with ENs) (Cox & Crane, 2014; Boelen & Kenny, 2009; Hutchinson et al., 2011; Craft et al., 2013; Rafferty & Kyriacos, 2016; Doggrell & Schaffer, 2016; Crevacore, Jonas-Dwywer & Nicol, 2016) (see Table 1). Excerpts from the interviews are presented in Table 2. These interviews highlight just some of the issues ENs face upon entry to university, providing rich personal insight about the experience of transition. The experience at CSU indicates there are a rare few EN students who choose to rescind their advanced standing for first year science, however, the financial penalty (government fees are invoiced on a per subject basis in Australia) discourages most from doing so regardless of their science related anxiety.

Table 2: Interview data – direct quotes

Sources (interviews):

1Fiona (a pseudonym) – mixed mode student. Published in Chapter 7: Cox, J., Logan, P. & Curtis, A. (2014). Being A Nursing or Paramedic Student in Rural and Regional Australia: Profiles and Challenges In A.T. Ragusa, (Ed.), Rural Lifestyles, Community Well-being and Social Change (pp.300-337). Bentham Science.

2Annette Ulph interview video published July 2015 on FirstDegree website – student studied by distance. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BO3SNaoOWec

3Christopher (Ace) Williams interview video published in Dec 2016 FirstDegree website 2016; Ace is an on-campus student.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XuCHgn1pPm4

At Charles Sturt University (CSU) between 150-200 students each year, who are qualified as ENs, are given direct entry to level 2 pathophysiology and pharmacology. These students are enrolled to study by distance education although some, as indicated by Table 2, opt to study science in face-to-face classes. Enrolment data indicate these students struggle with the induction into university study as well as engaging with their foundational science (Logan & Cox, 2015).

To help address this, Logan and Cox in 2014, developed and piloted a voluntary preparation workshop and website of resources: specific human bioscience materials in preparation for pathophysiology and pharmacology study, including information about learning styles quizzes, studying and writing in science. The website was made available to all students (n=207) prior to the session commencement and throughout the session (1624 visits to the revision topic content). The preparation website was structured to mirror the actual course site. It included a bioscience ‘memory jogger’ checklist that students could use to rank their confidence in specific bioscience topics and concepts, for example, factors that affect cardiac output. The memory jogger enabled students to decide which materials they most needed for revision. Evaluation of this pilot project demonstrated that ongoing access to the preparation website gave extended opportunities for timely revision of prior bioscience knowledge, supporting the study of the level 2 (more advanced) topics. Students were still accessing the site right up until the exam period. Of 196 students still enrolled by the exam period, those who utilised the site with an interaction rate on average of 37 per student achieved a pass grade or better whereas those who failed the subject had an interaction rate on average of 27.

Those who attended the workshop tended to make better use of the website. It was also apparent that those who attended the preparatory workshop utilised the website more effectively (56/207). Students noted that the opportunity to meet other students and lecturers assisted with managing anxiety and the social connections that were built helped them feel better prepared. Students who attended residential schools in the middle of the session commented that they felt utilisation of the website made them feel much better prepared than their peers (who didn’t use the site). Optional workshops have been continued each year, however, the numbers attending have varied greatly from workshop to workshop, probably due to the nature of shift work along with family commitments. These variables support further investment in developing a user friendly and engaging website with clarity of design to encourage access.

The case study approach embraces the diversity of information available for a phenomenon culminating in a detailed thick description; in this case study an outline of the challenges faced by the EN experience of transition to second year university study. The literature demonstrates a decade of research surrounding the issues of student struggles with biosciences study and highlights the challenges experienced in particular by ENs with advanced standing entry pathways to university from VET. The interviews highlight the emotional dedication to study and the impact the challenges have on progression. The evidence supports the building of strategies that embrace the FYE Principles and Pedagogy developed by Kift (2009) as the majority of these students are inexperienced in the expectations and ways of the university.

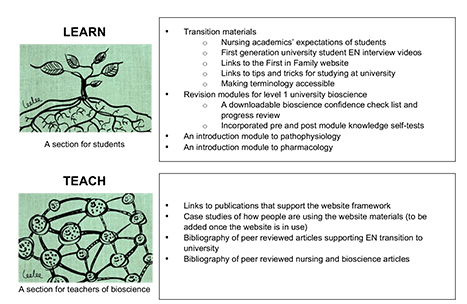

Armed with the evaluation of the pilot, the experiences outlined in student interviews and the results presented in the literature we set out to develop an open access website. The aim of the public website is to provide ENs with resources to assist them build their SE in readiness for entering the university in order to redress some of the risk associated with being non-traditional entry students. The website can also be used to support educators’, providing transition resources to support and inform their education processes. The inclusions and layout of the website follow the pattern of a conceptual framework (Figure 1) in keeping with a case study approach (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

Figure 1. The conceptual framework for the BioscienceEssentials2BRN website (http://bioscienceessentials.com.au)

The website has been specifically designed to be user friendly and culturally inclusive. An artist (Leigh West) produced ‘organic’ images for section placeholders and the banner allowing avoidance of stereotypical images of the ‘nurse’. Using the original ‘memory jogger’ tool developed for the pilot site as a starting point, the team used a consensus approach to refine the tool and provide a ‘confidence checklist’ for the students to self-rank their confidence in level 1 bioscience (Logan, Anderson, Hillman, vanReyk, Cox, Salvage-Jones, & Johnston, 2017). This facilitates students using the modules with which they are least confident first and reviewing their confidence once the module is completed. Further confidence building is provided through pre- and post-tests within each bioscience revision module. Links to external resources were evaluated for their appropriateness for the EN cohort as well as their appropriateness as examples of good bioscience content.

The website provides experience of the types of resources and the academic expectations that a new university student needs to navigate the tertiary system. As these students are essentially first year university students, the website design is in keeping with the first year experience (FYE) transition pedagogy and the FYE principles developed by Kift (2009). These include aspects of design relating to clear consistent and explicit assistance for transition, with focused and relevant content introducing foundation concepts and skill scaffolding (Kift, 2009). Griffin (2014) indicates the tailoring of support services are important but also recognises the financial challenges associated with such tailored support for students and the tertiary organisation. However, the “first few weeks of university are considered the ‘window of maximal risk’ for non-traditional, first generation students due to lower academic capital” (Wilson, Murphy, Pearson, Wallace, Reher & Buys, 2014, p. 3). A free to access website to which any university can refer these students can reduce some of the institution’s financial burden. This program will benefit:

Usage of the website will be tracked over the next two years to monitor total usage as well as patterns of use. In keeping with the outcomes of the literature review, direct impacts of the website will be monitored locally both in terms of usage and also in terms of student interest, engagement and academic outcomes. Longer term, an anonymous survey will be incorporated into the website to assist with feedback and the website does include an email address that will be monitored. Cases studies of implementation by academics will be undertaken enabling opportunities to review both student impact and how the website might be incorporated into formal offerings.

Refinement of the CSU pilot program for multi-institutional use could benefit all nursing students enrolled in pre-registration nursing degrees at any Australian university. Multi-site development of this package has illustrated some of the universalities of academic challenges for specific groups of students. The development of the preparation website will support EN qualified students during their transition to study within the university sector. It also demonstrated the strength and value of sharing innovation across tertiary institutions. Additionally, shared development of the resources enabled peer consultation and refinement of truly key concepts to address students’ foundational science revision needs. Thus, the conceptual framework we developed provides a model for others new to bioscience to inform their course development. An evaluation of the website usage and impact on EN transition will be undertaken to further explore the proposition that such resources can enhance student success in RN programs, particularly in bioscience-related components.

The website development was supported by a 2016 Office of Learning and Teaching Seed Grant now administered by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training (DET) and a Charles Sturt University Faculty of Science Leverage Grant. The institutional partners for the grant were Charles Sturt University (CSU – lead institution), University of Technology Sydney (UTS), and James Cook University (JCU).

Patricia Logan has been teaching human bioscience including pathophysiology and pharmacology for more than 15 years. Her main research area is related to tertiary science education for health practice. She developed and evaluated a pilot transition project ‘Preparation for Pathophysiology and Pharmacology’ for Enrolled Nurse students at Charles Sturt University.

Jennifer Cox is a lecturer in human bioscience, pathophysiology and microbiology for undergraduate health courses. Her work as academic lead in the Student Transition and Retention project culminated in the development and implementation of the SciFYE (Science First Year Experience) retention and mentoring program.

David van Reyk has been teaching anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology to pre-registration nursing students for more than 10 years. This has included for the last five years leading a bridging course in anatomy and physiology for Enrolled Nurses and Graduate Entry students’ transition to second year of a pre-registration program.

Elspeth Hillman is a Lecturer in Nursing, Midwifery and Nutrition, at James Cook University, Townsville. She has been teaching pre-registration nursing students for more than 10 years, with a particular interest in preparation for practice. Elspeth has contributed to publications on what science should be taught for nursing practice.

Judith Anderson has been involved in nursing education since 2002. Judith was involved in a ‘Step Up’ program for students’ transition from assistant in nursing, to Enrolled Nurse and then Bachelor of Nursing whilst being supported in their rural communities. She teaches in the Bachelor of Nursing program at Charles Sturt University.

Amy Johnston taught anatomy and physiology in the UK and Australia for more than 25 years. Her research in the behavioural and neurochemical basis of learning and memory, coupled with clinical and adult education qualifications, supports her expertise in nursing curriculum, course and resource design. Currently she holds a conjoint research fellowship between Griffith University and Gold Coast University Hospital in Emergency care.