Jessica Bownes1,

Nicolas Labrosse1, David Forrest1, David MacTaggart1,

Hans Senn1, Moira Fischbacher-Smith1, Maria Jackson1,

Michael McEwan1, Gayle Pringle Barnes1, Nathalie Sheridan1,

and Tatsiana Biletskaya2

1University of Glasgow, UK

2University of Cambridge, UK

Postgraduate taught (PGT) students encounter challenges and difficulties, some of which are specific to these cohorts. While these difficulties will vary between individuals, it is crucial that Higher Education Providers understand the needs of their students and support them in their transition to PGT level. This topic remains relatively under-explored in comparison to the research on undergraduate student transitions. The small number of PGT studies point to a historical focus of universities on supporting their undergraduate students, to the detriment of PGT students (Smith & Alsford, 2013).

The College of Science and Engineering (CoSE) at the University of Glasgow offers several PGT programmes covering all subjects represented in its constituent Schools (Chemistry, Computing Sciences, Engineering, Geographical and Earth Sciences, Mathematics and Statistics, Physics and Astronomy, and Psychology). While the number of students enrolling on PGT programmes steadily increases, the success rate for each cohort has remained consistently high (over 90%). In this study, we aim to identify challenges faced by students in their transitions to PGT programmes offered by CoSE. By surveying PGT students across six different Schools, we cover aspects of transitions from undergraduate (UG) to PGT, from one discipline to another, from overseas to Scotland, or from one teaching style to another.

The study was funded by the University of Glasgow’s Learning Teaching Development Fund as one of many studies aimed at enhancing the student learning experience and supporting student transitions in response to the University’s ongoing commitment to further increase student success rates.

Can we better understand the challenges faced by incoming PGT students to better support them? Do all students face obstacles when making their transition to PGT study? Do some experience more difficulties than others? What can we do about it?

We cannot expect PGT students to understand the workings of any new university and the skills they need to complete their studies successfully simply from the fact that they have obtained a first degree. Progression from successful graduates to Masters level study does not simply involve 'more of the same', or 'taking things to the next level' (O'Donnell, Tobbell, Lawthom, & Zammit, 2009): instead, PGT students need support to be able to effectively understand and access the range of information available to them, and adopt the valued practices at their university.

Much of the research focussing on supporting students transitioning into university is concerned with undergraduates, and more specifically first year undergraduates. This focus stems from the notion that UK universities reap many benefits through retention of their first-year students in terms of financial and reputational gains, as well as the fact that most students who withdraw do so in their first year of study (Wilcox, Winn, & Fyvie-Gauld, 2005). The advantage of this research focus is that we have an advanced understanding of the challenges faced by students moving from school or college into higher education. Two observations are common when describing how students cope with these challenges: the link between adaptability and emotional intelligence, and the development of a ‘learner identity’. It has been found that students who remain at university past their first year have higher levels of social intelligence than those who withdrew from study during their first year (Parker, Hogan, Eastabrook, Oke, & Wood, 2006). In response, it has been suggested that universities should support students in the transition to undergraduate higher education by teaching them adaptability, stress management and interpersonal skills (Parker, Summerfeldt, Hogan, & Majeski, 2004). Part of adapting to student life involve the negotiation of a new learner identity, and those students who are successful in this also tend to be successful in their studies; both the new institution and the past school or college are integral in this success (Briggs, Clark, & Hall, 2012).

Programmes that encourage peer-to-peer interaction result in students forming their own support networks and, consequently, they feel that their transition was easy in comparison to those who did not access the programme (Dalziel & Peat, 1998). This type of support can be linked back to the benefits of encouraging emotional intelligence: it was found that support from friends positively influences how well first year students adjust to university and this adjustment (both social and academic adjustment) is related to stress (Friedlander, Reid, Shupak, & Cribbie, 2007). We also recognise factors that make the transitions difficult for students. Communication and interaction with teaching staff at university is typically much more distant than relation to previous experiences at school or college. This change in teacher-student dynamic may contribute towards students feeling a loss of learner identity (Christie, Tett, Cree, Hounsell, & Mccune, 2008).

In contrast to first year undergraduates, postgraduate students are often interpreted as experiencing little or no transition phase as they begin their studies: they are considered as continuing as opposed to transitioning because they have already proved successful in a higher education environment. Tobbell, O’Donnell, and Zammit (2010), however, found that postgraduates do indeed experience a transition period, and this can be connected to their learner identity evolving further after their first degree. In some instances we can identify ways to support both undergraduate and postgraduate students alike, for example in a study that showed how peer mentoring and increased communication with staff benefited students across the board (Nelson, Kift, Humphreys, & Harper, 2006). It is interesting to note that the same study recommended targeted and tailored support for transitioning students (Nelson et al., 2006). It can be argued that postgraduate students may have very distinct needs from undergraduates, and especially that international postgraduates require more focussed provisions to be able to form positive learner identities and form social support networks (Brown, 2008).

Most crucially, we are not yet secure in this knowledge about postgraduate transitions because of the lack of detailed research carried out in this area. We thus started our study with a compilation of observations:

We used a multi-methodological approach to collecting data to investigate the issues mentioned above: we conducted two rounds of surveys, followed by a series of interviews, and finally a workshop. Data was collected at three stages in the academic year (beginning of semester 2, summer examination and graduation period) to gain a representative range of views as the students transitioned through their degree. All participants in this research were registered for PGT study in session 2015-16 in CoSE, and 116 out of 421 students took part.

The first survey was designed by the project team to gather anonymous feedback from PGT students regarding their experiences and expectations before starting their degree, during the first few weeks, and up to the time they participated (February 2016). Following ethics committee approval, all 421 PGT students were invited by email to participate and 42 responded.

The second survey conducted in June 2016 had two strands: a condensed follow-up survey for previous participants, to track changes in students’ perceptions of support from the University, and a second round of the original survey to capture feedback from students enrolled in January and those who did not take part in the first survey. The results of all surveys were analysed to identify trends in student opinions.

The surveys asked questions regarding challenges that students perceived as they prepared to start their degrees, upon beginning their studies and at the time they were surveyed. Answers were given in either a five point Likert scale of how much participants agreed with statements or were given in free form comment boxes which were later coded for data analysis.

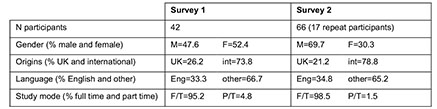

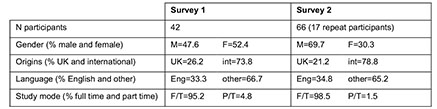

Table 1: Summary information of survey participants.

In order to gain a more in-depth view of students’ experiences, we invited all students (n=108) who had completed both surveys to take part in one-to-one interviews. Two recently graduated students volunteered and participated in anonymised semi-structured interviews in October 2016 that lasted for approximately half an hour. While we do not claim that the specific circumstances of the two students who participated are representative, the interviews allowed us to gain a better insight into some issues that were identified from the survey responses: we focussed on the themes of positive and negative experiences, opportunities and challenges, support received by the student, and changes in confidence throughout their degree.

The final stage of data collection was a workshop which aimed to explore solutions to issues raised in the surveys and interviews, as well as understand existing good practices and how they benefit students. 421 CoSE PGT students were invited to contribute and eight students participated. The workshop focussed on the challenges the students perceived at different stages of their degree and the support they received or required. We also asked participants to explore the idea of building a ‘postgraduate community’. In order to gather the most unbiased views, the moderator left the room to allow students to discuss four questions for 20 minutes; this conversation was audio recorded, but not guided by the moderator. After 20 minutes, the moderator guided the group through their answers to the four questions, which were as follows:

1. What were your challenges before starting your MSc and how could we have helped?

2. What help have you had with current challenges and is there anything else the University could do?

3. What challenges do you anticipate during the rest of your MSc and what support do you need from the University?

4. How do we build a postgraduate community?

We present the survey results in two categories, starting with the ‘First-time participants’ category which will examine data from surveys 1 and 2. Secondly, the ‘Identifying changing perceptions’ category will compare the results of survey 1 with those from the follow up survey. All quotes are presented verbatim and unedited.

The main advantage of repeating the same survey at two different points in the academic year is that we could compare the results of the two surveys to mitigate for the time of year being a factor in student perceptions. Demographic analysis of groups 1 and 2 (Table 1) show that they are comparable, except in gender, where there is a higher proportion of males in group 2.

Generally, the students found adjusting to the University of Glasgow easy or very easy (70% in survey 1 and 77% in survey 2). Confidence in their academic abilities was high at the time of surveying: the vast majority of students agreed or strongly agreed that they were confident overall about studying in their chosen MSc programme (86% in survey 1 and 83% in survey 2). When asked in what ways they felt confident they were equipped with the appropriate knowledge and skills to succeed, many pointed to prior education or work experience (see also House, 1995). Comments from survey 1 include:

I feel that my background in physics is very appropriate for the MSc programme I am currently enrolled in. I have encountered most of the mathematics before and just now, learning how to apply this knowledge to other practical fields.

I have previous working experience in the related field and love what I do.

I have sufficient field level hands-on experience for more than 10 years.

Very similar comments were made in survey 2:

I graduated with an undergraduate degree in a very closely related subject very recently. As I have not had a break from studying and have spent the last four years in full time education I feel equipped to succeed.

Before enrolling for this MSc, I was working full time for 2 years in an environment which provided me the right concepts for this MSc.

Conversely, students who were not confident in their abilities pointed to being unprepared as the source of their feelings. From survey 1, one participant commented:

I do not feel equipped enough well in the particular section of background knowledge. Different universities deliver the knowledge in many different way [sic] and with different timing as well. This is the most challenging part of my experience so far. I am not saying that I don't have what it [sic] needs to succeed in my Msc [sic] programme, I am just saying that in some subject [sic] the material that is taught here might differ a bit.

And from survey 2:

I do not have the same background as the other people in the department have which puts me at a disadvantage when it comes to completing this course.

The overarching conclusion resulting from data from first-time survey participants is that students’ perception of preparedness is key to their academic confidence. Therefore, ways in which we can ensure PGT students feel aware of the expectations of a PGT degree and prepared for their studies must be discussed. This topic was also a focus in the later interviews and the workshop.

By comparing the results of surveys 1 and 2, we gain an insight into how students’ perceptions of the challenges they face change over time. The first survey (n=42) was conducted at the beginning of the second semester and the follow-up survey, which surveyed the first cohort of participants (n=17), occurred just before the summer break.

The most remarkable finding here is that confidence in studying a chosen programme has decreased. While 86% agreed or strongly agreed they were confident in February, this confidence dropped to 76% in June. Interestingly, the abundance of students who strongly agreed that they are confident had not significantly changed (51% vs 53%) – only the confidence of those who ‘agreed’ had dropped. The percentage of students who felt they were not coping with the standard of work rose between the first and second surveys: only 7% of students disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement, “I am coping with the standard of work” in February, while by the summer this had risen to 18%. This could be a result of students struggling to implement effective time management strategies, and points towards students having an unrealistic expectation of the work involved in a PGT degree or of their academic ability in the earlier stages of their study, and the need for universities to set these expectations early on in the academic year. It must also be considered that the timing of the second survey coincided with the assessment period, where student are known to experience higher levels of stress and physical tiredness (Abouserie, 1994).

Another key finding is that better communication between staff and students is crucial to students’ perceptions of how well they were transitioning through their degree. In February, 74% of students said that they agreed or strongly agreed that teaching staff had been supportive at the start of the course. This dropped to 47% who agreed or strongly agreed in June, and 35% indicated that they disagreed or strongly disagreed that staff were supportive. Perception of support they were currently receiving from teaching staff had also decreased. In February, 77% of students agreed or strongly agreed that staff were supportive; this agreement dropped to 53% by the summer. Communication was identified as the biggest challenge:

It is not always clear what is expected from the MSc students regarding the labs and the supplementary tutorials. It would be very useful if it was made clear from the staff members.

While students were overwhelmingly positive about support received from supervisors and advisers of study, there were issues when students did not access this support:

I have not had any meetings with a supervisor throughout the program which would have been useful.

This may reflect a perception by students that support offered by programme directors happens mainly at the start of the programme. While this support is extremely valuable during the initial adjustment period of PGT study, its benefits may diminish on the long term as students progress through the year. Alternatively, since we know that student perception is strongly influenced by prior experience (e.g. House, 1995), the highlighted issues could also stem from a struggle to transition to more independent, self-directed learning. Our findings suggest that an ongoing programme of assistance would benefit at least some students and that it may be valuable to adjust the expectations of some students new to postgraduate study.

The above trend was not reflected regarding support from services such as library or accommodation services: 53% of students in February agreed or strongly agreed that university services were supportive, compared to 54% in the summer. This demonstrates how important and influential a good working relationship is between teaching staff and students.

The link between good communication between the University and students, and students’ perceptions of how well they are transitioning through their degree, was apparent in the interviews conducted in October 2016. When asked about challenges they faced at the beginning of their degree, Participant A noted:

[There were] issues with timetabling and particularly communicating timetable changes. There were some clashes that I thought would have been avoided if different departments communicated better with each other, and I wasn’t clear about how to sort these issues out at the start.

The same participant commented that his lack of experience in the subject was a challenge once he had started classes, but he was able to overcome this issue with the help of his lecturer:

I didn’t have some of the background knowledge required for some of the classes. The tutor was aware though, and found ways to communicate all the necessary information.

Participant B brought up similar issues surrounding communication at the start of his degree, with emphasis on online support rather than staff support:

Interviewer: Is there anything that you found negative in your experience?

Student: Yes, so maybe not a lot of information was put out on the website with regards to what we should be expecting. I decided to do IT because I got the opportunity with work in a financial institution after my first degree for about four years – I went into IT and stuff. I was thinking it was going to be more of hardware, but it turned out to be the other way around – all software. Very little bit of hardware. So that means that I was not well informed. So if I had known, probably I would have made such considerations or I would have placed myself for programming, because I had never done programming, and to do programming for three months and write exams on it – it was something else. There should be more information online with regards to what you are to expect.

Support from peers is just as important as support received from the institution. Participant B sought out help from his classmates as well as from his lecturer, and credits his peers with helping him through some difficult concepts in his degree. This help was so important to him that he strived to do the same for other classmates after his academic confidence improved. When asked what advice he’d give to someone at the beginning of a PGT degree, his response was:

Group [work] is very key. I don’t know how the university can hammer that. Obviously it’s all got to do with individuals and whether they want to be in a group with someone or no but if you identify someone in class, regardless of where a person is coming from, just say ‘I cannot know everything, why don’t we come together and we have assignment. Let me do my research, do yours, let’s bring it together. You may have something that I didn’t see in my research. I would also have the same. We bring it together.’

This reinforces the finding that PGT students require additional support before they commence their studies to ensure their success and confidence in their subject further on in their degree. This suggests that building a close-knit PGT ‘community’ would greatly ease the transition process for students. By encouraging communication and collaboration between students and their teachers and peers, academic confidence would grow and the jarring effect of having gaps in subject knowledge would not negatively impact transition.

All PGT students from CoSE were invited to participate in the workshop conducted just prior to graduation. Eight students participated, all of whom where international students and the majority of whom did not speak English as their first language.

When discussing some of the challenges they encountered before they started their degree, the group cited language barriers, as well as differences between the UK academic system and their home institutions. For example, a difference was that the semesters are a lot shorter than they were previously used to. Many were not aware of semester dates before they started.

The group then asked for information from previous students to be made available online for use after they accepted their place on a course, but before they enrolled on their degree. When discussing appropriate platforms, the university website was identified as the preferred host for a bank of information or discussion forum in preference to external websites such as LinkedIn and Facebook: the primary reason for rejecting Facebook was that it would exclude all prospective students in China, which currently bans access to the social media site. When asked whether they’d like staff to be involved or have access to these forums, no preference was expressed either way. Information they’d like included would be “tips on how to get acclimatised”, “advice on what to prepare” and “how to avoid problems and when you meet problems, who you should go to”.

One workshop participant struggled because they had an unrelated degree – a common issue which was brought up by other students in the surveys and the interviews. Another student suggested one-to-one tutorials with subject lecturers as a possible solution to this; although this is unlikely to be economically feasible, a group tutoring process may be more viable in the long term. When asked if their lecturers held office hours, the students said that it sometimes wasn’t clear how to access these.

The biggest challenge was problems surrounding communication between lecturers and students. A participant commented that some emails about a course query are sometimes not replied to. Students felt they could easily approach lecturers immediately after a class, but were less comfortable approaching teaching staff outside a classroom situation. Students were, however, accessing help from some of the University Services. One student discussed support that had been received from the career service:

We had a careers session, […] it was very interesting and helpful. It motivated us to make an appointment with the career service.

Anticipated challenges that the student expected in the future were unanimously exams and the final project. The group suggested study groups for students. They wanted the groups to be for students only, as opposed to staff-led groups, and ideally organised via social media.

Finally, while discussing a how to build a PGT community, students were in support of ideas such as shared coffee breaks, nights out and social media groups. There was evidence that the students were already socialising in their PGT group; it was noted that “we physics PGT students have chat group on Facebook and we organise a night out every week.” This group was for students only, so while there is a functional PGT community, it may be one that excludes staff. The group liked the idea of having regular coffee breaks together, but questioned how realistic it would be to organise, since everyone has different timetables.

While our study was not designed to assess the level of satisfaction of PGT students in STEM subjects at the University of Glasgow, it is complementary to the results from the latest Postgraduate Taught Experience Survey (Leman, 2016). While the 2016 PTES results revealed several improvements over the past few years, it flagged the issue of unmanageable workload as a serious concern for Higher Education Providers, one that must be examined further. The drop in respondents stating that the workload was manageable was strongest in the Physical Sciences area between 2014 and 2016 (Leman, 2016).

The apparent difficulty to cope with the workload later in the programme when students become increasingly focused on meeting assignment deadlines, revising and performing well in degree examinations, hints at the importance of the timing of academic support offered. A previous report published by QAA Scotland also concluded that PGT students need more than induction information to know how to study (QAA Scotland, 2013). By contrast, the more positive perception of the level of support at an earlier stage in the Masters programme happens when students are more confident that they will be able to meet assignment deadlines and be successful in their Masters.

Our findings, and specifically, our recommendations (detailed in the next section) on how to support PGT students before or as they start their chosen MSc programmes, echo those of Mellors-Bourne, Hooley, and Marriott (2014), and Mellors-Bourne, Mountford-Zimdars, Wakeling, Rattray, and Land (2016) who focused on the key factors that influence the decision-making process of prospective PGT students, and how Higher Education Providers support this process. For example, these studies highlight the importance of providing detailed information that is easily accessible to prospective applicants and new students on course expectations, including advice for success from former students.

The results we present here are also reminiscent of those of Smith and Alsford (2013), who identified very similar challenges in their study at the University of Greenwich, particularly in terms of level of preparedness of students, additional barriers to successful transition for international students, specific time constraints due to the short duration (normally twelve months) of the programme, and social integration.

Based on the results of the three surveys, the interviews and the workshop we conducted, we can recommend a series of best practices related to supporting PGT students as they transition through University. The novel value of these recommendations are that they are borne directly from PGT student suggestions. Of course, each institution will have a different variety of finite resources at their disposal, and some of these recommendations will be more realistic than others. When considering each recommendation, we have taken a variety of factors into account, including cost, staff and student commitment and efficacy.

1. To enable appropriate selection of courses, make available online detailed information about what is expected, together with insights from previous students; perhaps including a discussion forum.

2. Provision of ‘refresher’ material online prior to Semester 1 to help bring everyone to the same starting point, to address issues relating to different previous degrees.

3. Provision of ‘top tips for success’ generated by previous graduates, that is available to students prior to starting their MSc. Such tips might include information about how study in UK (for example) might differ from previous experiences.

4. Exploring ways of managing student expectations from the start; better information on assessment criteria and on using feedback and discussion of work with staff to improve performance.

5. Ensuring that students have access to lists of which staff to contact for particular queries, and perhaps even a FAQs site aimed at common issues for both home and international students.

6. Pro-active provision of support during later phases of the programme of study, rather than focussing delivery of information about support services within the first week or two only.

7. Generation of study groups during early courses as part of the “official” procedure, that might then act as models for students to generate their own study groups for later courses.

8. Fostering social interaction by organising events like ceilidhs and BBQs.

9. Review of workload across MSc programmes to ensure that this is realistic and that different courses have comparable levels of assessment.

The key finding from our research is that staff-student relationships are extremely important to students’ confidence and satisfaction. The perception of the quality and quantity of support received from staff dropped in repeat survey participants between the start and towards the end of their degree. We also found that students valued peer-to-peer support, with current students seeking more organised study groups, and graduates reporting the benefits of collaboration with classmates during their studies.

Finally, we identified that international students should be particularly targeted for specialised support: in all three methods of data collection, international students from around the world pinpointed that acclimatising to a new culture was their biggest challenge. Workshop discussions found that online information from previous students about the student experience at the University of Glasgow would be the most useful tool to support this particular group.

Nicolas Labrosse is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Glasgow. He oversees the MSc programmes offered by the School of Physics and Astronomy. He led the research project behind this paper. He is passionate about supporting MSc students throughout taught postgraduate study at the University of Glasgow. He can be found on Twitter @niclabrosse

Jessica Bownes is a PhD student at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC) and Graduate Teaching Assistant at the University of Glasgow. She was the Research Assistant for the project, and is interested in science communication and developing students’ scientific academic writing skills.

David Forrest is Senior Lecturer and co-ordinator of PGT in the School of Geographical & Earth Sciences at the University of Glasgow. He has many years of experience in developing and leading programmes in mapping sciences, and in dealing with student cohorts with widely varying origins and backgrounds.

David MacTaggart is a Lecturer in Applied Mathematics at the University of Glasgow. He is currently head of the Applied/Pure Mathematics MSc (PGT). His research interests are in theoretical mechanics.

Hans Martin Senn is a Lecturer in the School of Chemistry at the University of Glasgow. His research interests are in quantum chemistry and molecular simulations. He teaches Physical Chemistry at all levels and has been the head of the Schools’s postgraduate taught MSc programmes since their introduction in 2010.

Moira Fischbacher-Smith is Professor of Public Sector Management and Assistant Vice-Principal (Learning and Teaching) at the University of Glasgow. She has been involved in studying and developing transitions support for students for several years.

Maria Jackson is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Glasgow. She directs two genetics MSc programmes in the College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, and has particular interests in improving the student experience and in facilitating effective use of feedback by students.

Michael McEwan is a Lecturer in the Learning and Teaching Centre at the University of Glasgow. He coordinates the Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice, a programme of initial teaching development for new academics.

Gayle Pringle Barnes is the International Student Learning Officer for the College of Social Sciences at the University of Glasgow, where she co-ordinates an academic writing programme for taught postgraduates. Her particular interests include the postgraduate student experience and postgraduate writing.

Nathalie Sheridan is the Effective Learning Advisor for the College of Science and Engineering, working in the Learning and Teaching Centre of the University of Glasgow. Her background is educational science. She has worked in academic development since 2010, focussing on improving transitions and translating creative pedagogies into higher education.

Tatsiana Steven (Biletskaya) holds a PhD in Law and Economics from the University of Turin, Italy. Following that she worked in social science research at the University of Glasgow, at the same time graduating with an MSc Psychological Studies in 2015. She then worked as a post-doctoral Research Assistant at the University of Cambridge.