Jennifer B. Scally and Andrea Cameron,

Abertay University, UK

There is growing recognition of the value of working in partnership with students as a collaborative and reciprocal process (Bovill & Felten, 2016; Cook-Sather, 2016). While the drivers for staff-student partnership projects may centre on actively engaging students to effect change in a system in which they are personally invested (Healey, Flint, & Harrington, 2014), the investigation and analytic processes in which they become involved can enhance students’ research and enquiry skills (Lee & Murray, 2013). This case study blends a more traditional presentation of a research project with a reflective account of the experience of being employed as a research assistant prior to enrolling as a postgraduate research student. The literature relating to transition to postgraduate study is considered as background to the case study. An overview of the project and a synopsis of some of its findings are included to provide context to the reflective account. The ‘student as researcher’ perspective is examined in the context of developing skills that can enhance transition to postgraduate study.

Despite 63% of postgraduate students reporting difficulties in adjusting to this level of study (West, 2012), a lesser volume of literature exists in relation to this stage of transition. This is attributed to an assumption that undergraduate degrees prepare students to “generate, adapt and apply new knowledge” (Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013, p. 711) and that the move to postgraduate study is just a progression point (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; Tobbell, O’Donnell, & Zammit, 2010; West, 2012). However, attainment in relation to coursework performance is not a marker of preparedness to undertake postgraduate research (PGR) work (Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013). One of the key features of this level of study is the requirement to be autonomous and self-directed (Tobbell O’Donnell, & Zammit, 2010). The lack of structure and the level of independence required has led to students reporting feelings of disorientation and isolation (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013; Tobbell, O’Donnell, & Zammit, 2010). Cluett & Skene (2006) found that 80% describe being overwhelmed by the work demands of postgraduate study. Students at this level are expected to take personal responsibility for their learning and to change their practice and shift their expectations such that knowledge will no longer be gained through ‘transmitted messages’ but through ‘social processes’ (Tobbell, O’Donnell, & Zammit, 2010). Attrition can be as high as 50% for students on postgraduate research programmes (Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013) and aside from the capacity to adapt to different expectations, an altered skill set and the ability to manage external life influences (e.g. family, work demands – acknowledging that many postgraduate research (PGR) students will be working part-time to provide financial sustenance for their studies) are oft cited factors influencing dropout at this level (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; West, 2012). Therefore, time management could be considered fundamental to success at postgraduate level.

More students are enrolling for postgraduate study as they seek to enhance their employability and differentiate themselves from the now dense graduate market and increase their access to, or advance, professional careers (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; Masterman & Shuyska, 2012) and/or increase earning power (BIS, 2015). It is acknowledged that many will enrol for postgraduate study, potentially part-time, following a period of employment. Depending on the length of the absence from the higher education environment then there may be a requirement to up-skill particularly in the rapidly changing arena of information technology (Masterman & Shuyska, 2012). Postgraduate study requires advanced skills in information management as well as confidence and competence in using data analysis tools. However, digital literacy should not be assumed even for those transitioning immediately on completion of their undergraduate programmes. Subject discipline, higher education setting and the teaching methods used by their former lecturers will inform skill level (Masterman & Shuyska, 2012). Support and feedback on skill development from the supervisor with whom a good relationship has been developed is a strong determinant of a positive PGR experience (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; Zeng, Webster, & Ginns, 2013).

Transition at postgraduate level can be viewed as taking place in three domains – personal, social and academic (Hoffman & Julie, 2012) and mastery of the required postgraduate skill set and integration into a new community of practice are seen as key to successful transition (West, 2012). For those who undertake PGR studies part of this transition will be developing a new self-concept - that of being a ‘researcher’, though debate exists as to whether expertise in this domain can truly be developed within the timeframe of postgraduate study (Masterman & Shuyska, 2012). ‘Research preparedness’ is fundamental to student success, as is self-belief regarding individual capacity and capability to adjust to the ‘intellectual challenge’. A positive orientation toward research, level of motivation and of research self-efficacy, combined with familiarity with the research environment influenced by the level of exposure to active researchers all impact on this concept of ‘preparedness’ and the likelihood of success at PGR study (Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013). Understanding the research process, and prior involvement in scholarly activities eg. presenting, producing publications/research papers are also significant factors in relation to academic readiness for PGR programmes (Hoffman & Julie, 2012).

This case study explores the experience of engaging in a staff-student research project prior to enrolling as a PGR student and examines whether this helped to foster some of those skills described as necessary to success at this stage of study.

The research team successfully applied for internal grant money to support an investigation of the career destinations and preparedness for employment of the students who had graduated from an Abertay sports programme in the period 2000-2015. One of the conditions of the project funding was that a student researcher should be part of the project team. In order to simulate employment conditions the process of recruitment to this role was a competitive one, with 3rd and 4th year students invited to submit an application. The successful candidate was appointed subsequent to interview and their first task was datamining the student record system to generate demographic information (e.g. entry and exit point, place of origin, socioeconomic status) and contact details so that a mailing list for those graduates who would be eligible to be part of the study could be generated.

Records revealed that there had been 924 graduates from an Abertay sport degree programme during the period 2000-2015 but that there were only 452 valid e-mail addresses. Subsequent to ethics approval, a short visible four-item questionnaire was embedded in an e-mail to the graduates from one of the researchers, who was also a long serving staff member delivering on the sport programmes. The questions asked the students to detail their career history to date, any additional qualifications, reflect on how prepared for working life they had been when graduating, and what programme content had been most valuable in enabling them to transition to employment. The student researcher matched e-mail responses with the graduates’ demographic data and applied the Standard Occupational Classification system (ONS, 2010) to determine whether respondents were in graduate level employment.

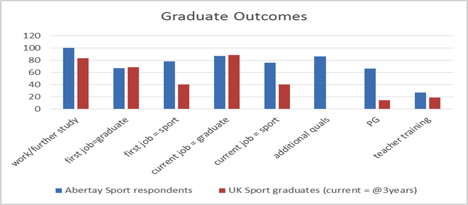

Approximately a third of the graduates (n=135) responded to the e-mail survey and together with a departmental database this allowed the outcomes for 360 Abertay sport graduates to be considered. First and successive graduate destinations, whether the role was a graduate or a non-graduate post, location of workplace relative to the region, Scotland, rest of UK, Europe or international was noted, as was any subsequent training or qualification that had been completed. Output was benchmarked to comparative data (Figure 1) revealing higher proportions of the Abertay survey respondents to be in work or further study, as well as being employed within the sports industry. When compared with sector norms there were similar levels of graduate employment, but many had gone on to study for additional qualifications. These were a mixture of workplace specific training, sport governing body awards, and postgraduate qualifications. Significantly higher proportions of the Abertay sport graduates completed postgraduate qualifications (_2 =54.2, p<0.01), many of these were with regard to teaching. HEFCE (2016) report that 18.6% of all graduates progress to teaching, however, substantively more (27%) of the Abertay sport graduates had made this career choice.

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents in a range of graduate outcomes – Abertay sport graduates compared to UK sport graduates

Three quarters of all respondents (77%) had felt prepared for their first job, and 87% stated that they had felt prepared for working life in general. Coaching, knowledge, experience, skills and time spent at Abertay were considered instrumental in this preparedness. ‘Placement’ and ‘research methods’ were the most cited aspects of the curriculum which had contributed to the transition to employment. The respondents’ comments included:

I developed and sustained crucial skills.

I have put myself forward for things and tried new things that I might have hesitated at before.

University is a great way to gain independence through learning and living.

Abertay placed a large emphasis on developing students as individuals.

It taught me to always question everything.

The project output enabled lecturing staff to reflect on curriculum content with regard to preparing students for employment. The demographic characteristics of the graduates in general, did not influence graduate outcomes – however, those who articulated onto their degree programme from college were significantly less likely to progress to postgraduate study (χ2 = 6.35, p<0.05).

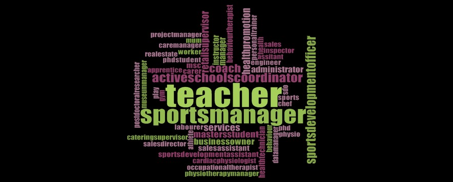

Figure 2: Current occupations of graduates from Abertay sport programmes.

Collation of the graduates’ career destination responses allowed visual representations to be produced (e.g. Figure 2). These have subsequently been used as marketing materials for the sport programmes. However, the research team recognise that the survey respondents were a self-selecting population and that by removing anonymity within the e-mail that those who had a ‘good news graduate story’ to tell may have been more inclined to respond potentially skewing the project findings.

Engagement with the project for the student research assistant provided a distinctive opportunity and this case study details the development aspects associated with this.

I applied for the research assistant role as I was interested in pursuing postgraduate research upon the completion of my undergraduate degree. It had been explained to me at the interview that a key task would be to do the datamining of the student record system, to also create and maintain a database of the graduates’ responses, and to help with aspects of the data analysis. I relished the opportunity to hone these skills as a researcher and gain greater understanding regarding what research involves. I also wanted to gain more confidence in this area before making a final decision regarding enrolling for PGR studies. I knew that if I did decide to register for a PGR degree I would probably have to self-fund so this also provided me with an opportunity to earn money to pay the fees.

I had flexibility in the time I gave to the post but decided to work one day each week, so that I could give dedicated hours to the project and have a regular meeting time with the staff. Hall (2010) reports that 94% of full time undergraduate students undertaking part time employment struggle to balance their time, and conscious of this, I wanted to ensure that I was able to honour my commitments. However, it was harder to manage my time for the project in the later stages of the post as my undergraduate dissertation was due and I was starting to look for external employment. I quickly learned that self-discipline and time management were integral parts of being an effective researcher, particularly if I wanted to ensure that my academic performance in my undergraduate studies did not suffer (Hall, 2010).

My role was titled ‘assistant’ however, when I attended meetings, I felt that I was able to contribute a lot more than I initially expected. Both members of staff respected my input and I felt like a valued member of the research team. I was provided with clear and well defined expectations for my role; preventing any problems regarding the supervisor-student relationship (Cornelius & Nicol, 2016). I found no difficulty in undertaking the post, assisted by the research topic of employability, as this had been embedded in our curriculum. However, it became evident that the work would only have suited a senior student because of the requisite skill set and knowledge, something that the staff had considered during the recruitment process. They were also conscious of the competing demands on my time and did check on how I was balancing my deadlines.

Any input that I had was listened to and in some cases implemented. I had not expected to be given as much trust and autonomy as I was.This was something that I greatly appreciated and which fostered a positive mentor-mentee relationship built on reciprocated respect (Grant & Graham, 1994). I refined my skills in creating and maintaining a database; in interpreting and analysing quantitative and qualitative data; and in organising and prioritising tasks. Confidence in my ability to undertake research was heightened, and reaffirmed my decision to apply for postgraduate research. Hughes, Brown and Calvert (2008) found that at least 50% of those who held research assistant roles during their undergraduate degree undertook PGR as opposed to the undergraduate norm of 14.2%.

Something that I did not appreciate prior to starting the post was the insight I gained into the field of employability, and knowledge and skill acquisition in undergraduate degree programmes. During the time frame of the project I also made my own transition from undergraduate study to sports alumni, graduate employment and then subsequently, into postgraduate study. Consequently, there was also a personal dimension to the interest generated from being part of the project team and considering the graduate outcomes (Figure 1).

My own expectations and experiences of university education – to heighten critical analysis skills, enable personal development, and enhance confidence (Whitehead, 1967) – were mirrored in some of the respondents’ comments.

Subjects within the study had cited placement and research methods as the most prized parts of the curriculum in terms of enabling transition to the next stage beyond graduation. I discovered that a significantly higher proportion of Abertay sport students’ progress to postgraduate study therefore validating my current interest in the experience of transition to this level of scholarship.

Throughout the project, I felt confident in my ability to try new research methods. Both members of staff provided me with high levels of autonomy as a research assistant whilst mentoring me. This was the most valued aspect of the role. I was also very grateful for what I perceive to have been a unique experience whilst an undergraduate student.

On completion of my Sport and Exercise Science degree, I applied for a project coordinator role with British Blind Sport. I had been a volunteer disability sports coach for a number of years, but I believe that one of the key reasons that I was the successful candidate was due to the experience that I had gained as a research assistant. My employers were very interested in hearing how I had created and maintained the database as well as analysed and reported information. I do not think that I would have obtained this post without this work experience as obtaining an undergraduate degree is only one facet in terms of preparedness for the graduate workplace (Gazley et al., 2014).

In the role at British Blind Sport I undertook more in depth research than had been requested and I would not have had the confidence or skills to do so if it had not been for my time as a research assistant. Additionally, the insight that came from the sports’ alumni data gave me an understanding of the role Bachelors’ degrees have in shaping people into graduates. Reviewing all of the study responses has given me a valuable perception of how Abertay alumni are using their sport degrees in the employment context. I feel that knowing this has given me an advantage when looking for my own employment opportunities, as I have been more readily able to articulate in my Curriculum Vitae and at interviews the skills that I have obtained during my time at university. Subsequent to my first graduate job with British Blind Sport, I was successful in gaining a similar role with Scottish Disability Sport. It is my belief that I would not have my current post without the supplementary skills and confidence that came from doing the research assistant post.

I applied for the research assistant role on the basis that it would be a fantastic opportunity to take part in a live project whilst being mentored by two senior members of staff with lots of experience. This was indeed what happened and I felt this enabled me to develop further as a researcher. It was the mentorship aspect specifically which I feel enhanced my confidence beyond what I had gained from completing my undergraduate degree and was the impetus for me ultimately submitting a Masters of Science by Research application. Whilst my Bachelor’s degree provided me with a skillset to undertake postgraduate research this was enhanced as a result of my time as a research assistant. I have been able to transfer the database and analysis skills to my current PGR studies, and have also found the skills gained in organising and prioritising tasks, invaluable. Working in a research role with a high degree of autonomy gave me a vital insight into the daily reality of what scholarship at this level would require. If I had had further time in the role, I would have relished the opportunity to engage with the reviewing literature and writing up aspects of the project as it would have been of additional value for my PGR programme. When employed as the research assistant, I was balancing this commitment with my undergraduate degree and my club and national level coaching posts. This really challenged my time management skills, and as a self-funding PGR student, working part time for Scottish Disability Sport, I have been able to transfer the lessons learned in how to be effective with my time to my current studies. I feel that the skills and experience required for postgraduate research are greater than that taught within undergraduate degrees and it cannot be assumed that an undergraduate degree ensures preparation for PGR study (O’Clair, 2013). Therefore experiences of working in partnership with staff on research projects, as in this case study are invaluable, and consequently should be more widely available within the sector.

The recruitment and retention of postgraduate research students is of significance to university departments (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; Masterman & Shuyska, 2012), as the number of PGR enrolments and completions allows them to evidence how their research environment supports and extends research capacity. Student success is an essential part of this and where ‘research preparedness’ is key (Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013). The quality of the PGR experience is also an imperative (Ginns, Marsh, Behnia, Cheng, & Scalas, 2009). Familiarity with the research environment influenced by the level of exposure to active researchers all impact on this concept of ‘preparedness’ and the likelihood of success at PGR study (Shaw, Holbrook, & Bourke, 2013). Knowledge of the research process and engagement with scholarly activities (presenting, publishing, academic writing) can also ease the adjustment to the expectations of PGR programmes (Hoffman & Julie, 2012).

The research assistant for the featured case study outlines how working with staff on a ‘live project’ and the mentorship that this afforded specifically built her confidence for PGR study. She reflects that one of her disappointments was not having the opportunity to be engaged with the reviewing and write up of the project prior to commencing PGR studies, recognising the added value that would have come from these tasks. However, it is anticipated that engagement with writing this current paper addresses this potential deficit and supplements the data analytic, organisation and oral presentation skills which were developed.

The model of self-funding PGR studies is not unique and, as reported here, students will often be working part-time (Hoffman & Julie, 2012; West, 2012), so time management, as voiced, is critical to ensure that project study goals are progressed within the indicated timeframe. The culture of ‘self-reliance’ which features in postgraduate study can be an isolating one (Tobbell, O’Donnell, & Zammit, 2010). Autonomy and self-direction run as a narrative theme through the research assistant’s account of what was required for the role but also how this prepared her for ‘the daily reality of studying for a research degree’. She also makes reference to ‘becoming a researcher’ and applying for the post on the basis of the insight that this would give her in this regard. The emergence of a new identity is also explored in the work of Masterman and Shuyksa (2012). They assert that for those who undertake PGR studies part of this transition will be developing a new self-concept – that of being a ‘researcher’. A similar theme explored by Tobbell, O’Donnell, & Zammit (2010) who discuss the PGR process as having the capacity to transform the learner’s identity. There is however, disagreement in relation to whether expertise as a ‘researcher’ can realistically be developed within the enrolment period of postgraduate study (Masterman & Shuyksa, 2012).

One of the markers of a ‘true learning’ experience is that it should be ‘transformational’ (Barnacle, 2005) and challenge pre-conceived ideas, for example of the type of researcher that an individual wants to be. In the presented case study it is evident that the research assistant’s skill set was expanded and she was willing to experiment with new methods, broaden her approaches to research and engage with less familiar analytical tools. ‘Transformational’ does not yet emerge in the current narrative but it is acknowledged that the PGR studies are still in progress. However, reference is made to a ‘unique’ experience and the reflective aspects of the case study, give a clear sense of knowledge and skills being gained within the domain of employability as well as research. It is interesting to note that immersion in the data set arising from the alumni project has allowed the research assistant to more judicially articulate within her Curriculum Vitae what she has gained from her degree. Something which she feels has conferred an employability advantage, discrete from the enhancement of skills that accompanied the project.

The value of this opportunity emerges in the student narrative and with a growing evidence base regarding ‘student partnership’ work (Bovill & Felten, 2016; Cook-Sather, 2016; Healey, Flint, & Harrington, 2014), it challenges institutions to consider if collaborative projects of this type can be more widely available. The capacity to enhance analytic skills as well as self-directedness, as intimated here, are evident (Lee & Murray, 2013). Engagement in these projects can also inform the future career decisions of the student partners.

“The process of doing research sets you up to do more” (Winn, 1995). Therefore, opportunities to foster the skills and capacities that a postgraduate research student will need should support a successful transition. The presented case study reinforces this. However, it is acknowledged that not all prospective PGR students will get experiences similar to the one afforded here. Involvement in this project confirmed for the student that postgraduate research was the correct next step for her to take. Engagement with undergraduate studies is not an automatic means of preparation for PGR programmes, and in the knowledge that almost two thirds of students report difficulty in making the postgraduate transition, the advantage of creating ‘student as researcher’ partnership posts becomes evident. The challenge therefore lies with institutions to consider how to employ or use students as volunteer research assistants on live projects. The research capabilities, self-direction, time-management and confidence that this may foster could ensure that the ‘research preparedness’ which is considered key to PGR student success is developed prior to enrolment.

Jennifer B. Scally, an MSc by Research student at Abertay University, graduated with an upper second class Honours degree in sport science from the University in the summer of 2016. Jennifer works part-time for Scottish Disability Sport and was a research assistant for the project examining long-term career destinations of sport graduates.

Andrea Cameron is the Head of School of Social and Health Sciences and Intellectual Lead for Teaching and Learning at Abertay University. Andrea is both a sport scientist and a registered nurse. Her interest in heightening skills, competency and employability in graduates derive from her clinical nurse teaching experiences. Email: A.Cameron@abertay.ac.uk