Hope Christie1 and Karl Johnson2 1University of Bath, UK 2Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK

Higher Education institutions have an “[…]obligation to take reasonable steps to enable [their students] to be successful” (Thomas, 2012, p. 7).

At the outset, we had no idea about ‘Enhancement Themes’, ‘Student Transitions’, ‘Retention’, ‘Enhancing Learning and Teaching’ and the like; we were just concerned for our fellow students and did what was reasonable and made good common sense. It was a happy coincidence that the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, Scotland, (QAAS) was focusing on the Enhancement Theme of Student Transitions – and furthermore that this work was being overseen by Professor Roni Bamber, from our own alma mater Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh (QMU).

The success of students at any institution relies on their engagement and support, and in recent years QMU has worked to increase and improve efforts in this regard. Within QMU’s School of Arts, Social Sciences and Management (ASSaM) these efforts are reflected in inter-related attentions to student retention, and enhancing the learning and teaching experience – for staff and students alike. The progression of students through higher education (HE) impacts upon their sense of identity and belonging within their institution, and for working-class students in particular, the acquisition and/or challenging of their cultural capital (Lehmann, 2014; Reay, Crozier, & Clayton, 2009).

Much of the transitions literature in recent years, whether in response to the QAAS or otherwise, has focused on the more obvious undergraduate (UG) student transitions into and out of HE – with skills and employability at their root (Briggs, Clark, & Hall, 2012; Farhat, Bingham, Caulfield, & Grieve, 2017; Whittle, 2015). While undoubtedly important, a glance at the QAAS ‘Transitions Map’ by the end of the first year of the theme highlighted that little concern had been given to transitions between levels - though admittedly, slightly less so now (QAAS, n.d.). Arguably, this detracts from the lived experience of the student during their UG career, and thus perhaps less attention paid to supporting the successful continuation of students – which would surely be counter-intuitive in an environment of widening access in Scottish HE (Gallacher, 2014; Ianelli, 2011). Successful student transitions are of course not solely the responsibility of professional and academic staff, but rather rely on an ongoing dialogue between staff and students, and an engagement with the curriculum that is open to adaptation and appropriate to each subject division (Briggs et al., 2012; Thomas, 2012; Woodfield, 2014). Indeed, Bovill, Cook-Sather and Felten (2011) make the case for an ongoing dialogue in co-creating curricula, thus engaging students and enhancing the learning and teaching experience for staff and students alike.

Our own experience as social science UG students at QMU – and that of many others – was that despite an understanding and supportive faculty, it was the advice and guidance of peers that made a deeper impact on anxiety. Areas of concern ranged from assessments and time management – to self-belief and social media. We set out to write down and share our own experience of our fourth and final year of UG study, simply to try to help ease the anxieties of the year groups that followed us, and to encourage them in their academic and personal development. Thirty-something pages and over 10,000 words later, we had written Don't Panic: The Psych/Soc Student's Guide to Fourth Year (the title is a loving reference to Douglas Adams).

Working as a Psychology Technician at QMU during academic year 2014/15 (just after we had both graduated from our Masters degree there), Hope spent much of her time in the psychology laboratory or passing through a common area outside the teaching staff office, where opportunistic students from the Division of Psychology & Sociology traditionally work and socialise. Offering pastoral support to anxious UG students indicated that successive year groups shared similar anxieties in relation to their academic abilities and progress, yet did not seek out the full extent of support available to them. Hope found that the fourth years, in particular, deemed some questions/concerns as being “too stupid” to bring up with their dissertation supervisors or lecturers on other modules – and those students that did were not comforted by the advice of staff for long.

To be clear, the Division staff have supported and continue to support and encourage their students to the fullest of their ability, despite being a relatively small team with a significant number of students and other responsibilities. Perceptions of peers and instructors, however, meant some students became less likely to openly ask for help or discuss issues they found challenging. Instead, they sought out guidance from one another, postgraduate (PG) students and ourselves as people who were perceived to ‘better understand what they were going through’.

The lived experience of these students was very similar to our own – indeed, our collective experience at QMU mirrored that of students elsewhere (Greenbank & Penketh, 2009; Kite, Russo, Couch, & Bell, 2014) – so Hope struck upon the idea of a ‘Division guide’ for them. We consulted this final year cohort (in social spaces such as the psychology lab and the common area) about what they would have liked to have known at the beginning of the academic year, and combined it with the experience of our own graduate cohort (engaged via Facebook) to write the sections that became Don’t Panic. These generally informal conversations not only helped organise our thoughts on how to structure the guide, but also in how we would communicate with readers through it.

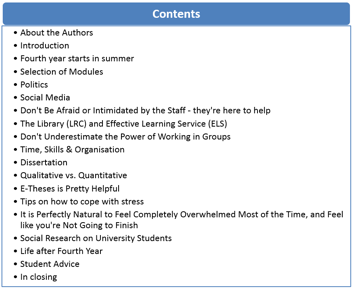

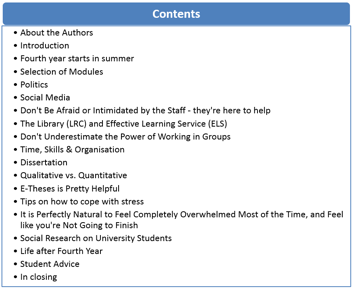

Our message is intended to be clear from the cover page – an image of a blue ‘thumbs-up’ hand with “Don’t Panic” in bold type underneath – which aims to convey encouragement and a positive attitude, while resembling imagery associated with Facebook (for students especially ‘present’ on social media) and The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (for ourselves and other appreciative students). This playful and hopefully relatable approach to design and content is furthered by the inclusion of memes, pictures and references from popular culture that help communicate who we are to the reader, and embed the sense that Don’t Panic is the work of ‘real’ people. Written as an informal and straightforward companion piece to the UG dissertation handbook, Don’t Panic is designed to cover the full ‘life cycle’ of the Honours – from the summer before semester 1 starts, to the early days and weeks after final submissions and graduation. Over the course of the guide the sections (Figure 1) are arranged to reflect this ‘life cycle’.

Opening sections set the scene (and our tone) for what to expect and how to begin to prepare for fourth year. Thinking ahead in terms of module choices and dissertation topics (while looking back at previous years for inspiration), anticipating the pressures that some students may feel from social media and classmates, understanding the relationship between students and supervisors; all areas that may seem obvious with the benefit of hindsight, but which are beneficial to be made more fully aware of in advance. Managing expectations at all levels of transition can help students adjust to their new situation and cope better, contributing to more positive/successful outcomes (Briggs et al., 2012; Jones, 2008; Thomas, 2012; Woodfield, 2014).

Throughout Don’t Panic, we provide good-humoured but frank information and guidance that is applicable to students on three UG degree programmes: BSc Psychology; BSc Psychology & Sociology, and; BSc Public Sociology, a newer degree at QMU. There are several instances where relevant information diverges, of course, and so coloured boxes highlight areas of discussion more specific to one programme or another – with Psychology boxes written by Hope and Sociology ones written by Karl, as befits our own expertise. This has proven particularly useful in the mid-sections of the guide (Time, Skills & Organisation; Dissertation; Qualitative vs. Quantitative) which cover much of the ‘labour’ involved in fourth year on these three degrees. Indeed, the section on dissertations accounts for around a quarter of the guide to address as many of the concerns and feedback from the students and colleagues we consulted with as possible.

The guide closes with short sections offering advice on coping with stress and high emotions (with directions towards established support networks for those that feel they may benefit), words of wisdom from recent graduates (as below), some pointers on life after a UG degree, and a full-page ‘pick-me up’ entitled It is Perfectly Natural to Feel Completely Overwhelmed Most of the Time, and Feel like you’re Not Going to Finish.

Pretty much writing off January to April and not taking on too much outside of uni during your 4th year cause you just don’t have enough time. Also what I found helped me with my dissertation was talking about it a lot, even to those external to uni really helped. The more I talked it through and bounced ideas around with other people really helped bring it to life. Also don’t be afraid to contact external organisations for a starting point/help with your dissertation, the charities I contacted were super helpful and really saved me some work by pointing me in the right direction. (Sociology graduate)

I wish I'd have been prepared for how hard and busy the last semester was and that I didn’t take on as much outside uni and stretch myself so thin. I also got really anxious and it got worse throughout the year so being reminded to look after myself and take time away from it too. Being super organised was handy too (even if your friends do slag you off for having a spreadsheet!). (Psychology graduate)

Figure 1: The contents of Don't Panic: The Psych/Soc Student's Guide to Fourth Year.

Colleagues at QMU - notably the Division of Psychology and Sociology’s previous Head of Department and their Acting successor, and a Psychology lecturer – have been supportive and enthusiastic from the beginning. A pdf first draft version of Don’t Panic was shared with the 2015/16 fourth year cohort from BSc Psychology & Sociology, and BSc Public Sociology, before their first Honours semester began. Internal funding was awarded to cover the production of physical copies of a refined third draft guide which were distributed to students from across the Division’s 2016/17 fourth years at the beginning of their first semester. This funding will also cover time spent on creating and evaluating a Bristol Online Survey (BoS), where the 16/17 cohort will be asked to provide feedback on the guide, and their experience of their final UG year.

We have presented Don’t Panic at conferences held by the Higher Education Academy (HEA) (Christie & Johnson, 2015), QAAS (Uytman, Johnson, & Christie, 2016a), QMU (Uytman, Johnson, & Christie, 2016b), and the University of Bath (Christie, 2016a); and disseminated in the Enhancement Themes newsletter (Johnson & Christie, 2016), and The Psychologist (Christie, 2016b). The British Academy is also considering the guide as part of an ongoing project reflecting on teaching excellence in the Humanities and Social Sciences.

Our conference appearances, and especially the Psychologist article, have gathered feedback from staff and students at institutions across the United Kingdom and from as far away as Australia. Academics and support staff have shared their belief in the benefit of a similar resource in their own departments – and for each UG level, not just the final year; while students have expressed a need for the kind of guidance and communication we offer in the guide. As a result, we quickly adapted a more generalised version of the guide (removing details specific to QMU) and shared it with interested parties. This version of the guide was distributed to social science faculty at institutions including University of Westminster, Nottingham Trent University, University of East London, and Oxford Brookes University, and (to our knowledge) has been shared with their final year students this academic year. Other divisions within QMU and the University of Bath have also expressed interest, so we have created a ‘Don’t Panic’-template for other academic disciplines (UG as well as PG), in the hope that students from different universities, departments and backgrounds can tailor their own guide to better suit their needs. In one case, a group of students, who all have disabilities, requested the guide and have offered to share their notes on their own experience.

It is intended that the BoS will also be shared with interested students from other institutions, so that they too may feedback and have their own advice (such as above) feature in any further development of Don’t Panic. In the meantime, QMU staff are adapting the guide into an online ‘wiki’-type format which will incorporate a student-produced short film featuring interviews with recent graduates.

Originally a well-intended gift to people who found themselves in the same boat we’d once drifted around in, the Don’t Panic guide has attracted more interest and afforded us more opportunities in academia than we would have expected. A further unanticipated outcome has been our steadily growing involvement in, and understanding the bigger picture of, literature and issues relating to the enhancement of teaching and learning, widening access and retention, and transitions. We reflect on these matters, from both an academic and a professional perspective, here.

The final year of UG study is in many cases the culmination of an individual’s educational career – where they may feel the freedom to explore their own academic thinking, and feel challenged to prove their aptitude in their discipline, in equal measure – with the dissertation being a main expression of independent learning (Brodie, Penny, Windram, & McCallum, 2015; Greenbank & Penketh, 2009; Kite et al., 2014). Whether considered in Bourdieusian terms of field, habitus and capital, as per Lehmann (2014), Reay et al. (2009), and Tranter (2003); or as an arguably more holistic and interactionist conception of an evolutionary lifecycle, as per Lizzio (2011) and his followers (Chester, Xenos, Elgar, & Burton, 2013); the Honours student/learner identity is tested on all fronts. The success, stability and future of this identity is in no small part dependent upon the support, encouragement and management of expectations received in teaching and pastoral guidance, according to Briggs et al. (2012). Although initially forming upon transfer to HE, the student/learner identity is developed over the course of the UG career as the individual becomes an independent learner confident in their own critical abilities.

A flood of information washes over students in their first year of HE, as well as it being taken for granted that they arrive at university armed with certain learning and teaching competencies. It is therefore incumbent upon faculty and support staff to help students navigate their way around HE (Briggs et al., 2012; Jones, 2008; Thomas, 2012; Tranter, 2003) – not just in their first year, but we believe at each UG level from beginning to end. Christie, Barron and D’Annuzio-Green (2013) highlight the crucial point that to become successful independent learners, students must believe in their capacity to do so. Encouraging students and inspiring some amount of confidence in transitional guidance is arguably as important as improving academic skills.

Tailored student guidebooks and resources like Don’t Panic (when developed with care and investment) provide an opportunity to encourage potential, as well as help staff and students to communicate, understand and appreciate each other’s respective expectations at each transitional level of HE (Briggs et al., 2012; Brodie et al., 2015; Whittle, 2015).

The Enhancement Theme focus on transitions from 2014-2017 has sought to engage HE institutions in Scotland and work towards a framework for HE transitions across the sector (QAAS, 2015). One branch of this has been the online Transitions Map (QAAS, n.d.) indicating the specifically ‘transitions focused’ initiatives being run and developed by institutions during this period, grouped into particular types of student transition. From the off, it is evident that the map and the theme overall are more suited to disseminating not just types of transition but also types of practice; i.e., initiatives which are funded/temporary/have a catchy name, and does not communicate as effectively the good-natured and ‘everyday’ micro-efforts of staff in supporting students. Presumably such ‘mundane’ support, personal investment and positive attitudes will be discussed in the forthcoming framework documentation in a similar vein to the HEA What Works report from Thomas (2012).

A large proportion of initiatives on the map (QAAS, n.d.) are in some way connected to access and the initial transition into HE – and indeed across much academic literature concerning learning and teaching in HE (Briggs et al., 2012; Chester et al., 2013; Maunder, Gingham, & Rogers, 2009), the same focus is apparent.

And quite rightly so, for it is this initial transfer into HE that can be the most notable ‘shock to the system’ for many individuals in their experience of education. Students may feel like ‘fish out of water’ as per Tranter’s (2003) discussion of the challenging of habitus – internal organisation and understanding of preferences and behaviours, in relation to acquiring social and cultural capital – for HE students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Tranter and others (Lehmann, 2014; Reay et al.,2009) have evidenced that the student/learner identities of individuals from working class and similarly-recognised social backgrounds experience anxieties around new practices and forms of capital upon entering HE and the socio-cultural environment of the university itself. Their successful transition into and through HE relies on learning new ‘rules’ in an environment often perceived as middle class and somewhat unknown. As first-generation university students ourselves, from backgrounds that may be described as working class or by similar status, we (and some of our peers) certainly felt anxieties around our new environment and some amount of habitus clivé (Friedman, 2016).

It is for this reason that in Don’t Panic we remind students of the resources available to them at QMU (e.g., the library, previous dissertations online, the employment service, etc.), and offer advice on topics such as choosing modules or relationships with peers and faculty. The lengthy dissertation section of the guide is ‘step-by-step’ to some extent. We have sought to explain at least some of the ‘rules’ of this field of education, and offer some discussion of the practices and capital that a student habitus may encounter. There are examples of our own experience of fourth year alongside references to academic research into the lived experience of university students, to provide context and ‘normalise’ our readers’ own time at QMU.

Tailored student guidance at every level, whether in the form of Don’t Panic, or current efforts to improve longitudinal induction for Direct Entry (DE) students – who likewise rely on developing themselves as independent learners (Christie et al., 2013; Jones, 2008) – in ASSaM at QMU, can support student transitions by helping all students learn the ‘rules’. Coincidentally, Brodie et al. (2015) at Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, have developed a dissertation-focused online resource for DE students, citing the same themes of expectation management and supporting independent learning. As far as we know, Brodie et al.’s e-toolkit does not broach issues outside of the dissertation, such as what happens afterwards.

The closing sections of Don’t Panic encourage students to maintain self-belief, and feel prepared and capable to face challenges in the completing their UG degree (there is an argument that we should perhaps also open discussion on choosing not to complete the Honours year). The guide also discusses options for after graduation – whether going into a postgraduate programme, looking at careers (with a list of some graduate jobsites to start from), or taking a break to regroup, and getting a hobby. We found, in talking to our peers, that the end of the UG career can result in mixed emotions; pride in one’s achievements, loss of purpose, excitement/anxiety about entering the world of work or whatever else awaits in post-degree life.

Not surprising then, that another main feature on the Transitions Map (QAAS, n.d.) is the proportion of initiatives across the sector which are concerned with student transitions out of HE – or more specifically out of UG education, either supporting the step up into postgrad studies or the leap into the workplace. The latter option is well-represented by institutional support in gaining skills and developing the employability of students. The merits of the increasing sector concern with embedding ‘employability’ into learning and teaching aside, it is surely the responsibility of institutions to help equip students for the transfer out of HE, whatever that may be (Jones, 2008; Kite et al., 2014; Farhat et al., 2017).

As access to and participation in education at all levels has expanded in Scotland in living memory, and thus social mobility has improved (Gallacher, 2014; Iannelli, 2011), so too has it become imperative that students graduate on as much of a ‘level playing-field’, in terms of social and cultural capital, as possible. However, despite the current focus on widening access to education across social backgrounds in order to improve economic prospects (Scottish Government, 2016), there are a number of complex and interconnected contributing factors across many fields in society which careers skills programmes alone cannot tackle (Gallacher, 2014; Iannelli, 2011; Woodfield, 2014).

Jones (2008) provides a summary analysis of a number of reports and papers into student access, transitions, retention and success; the take-home message being that HE staff should strategically and collaboratively develop proactive, adaptable, integrated and student-centred approaches to all of the above. This is envisaged as work that spans the whole HE experience. It is, as Thomas (2012) plainly states, the responsibility of HE institutions – both academic and support staff – to meaningfully engage with endeavours in this regard. This work should be just as important to institutions as the research and knowledge exchange outputs that universities typically put more stock into (Thomas 2012).

As alluded to elsewhere in this discussion, HE in recent years – and noticeably in Scotland – has turned attention more to student engagement and interconnected issues (Bovill & Felten, 2016; Scottish Government, 2016). In particular: the widening of access to HE for individuals who are first-generation, or from less-advantaged backgrounds, or otherwise (somewhat unhelpfully) described as ‘non-traditional students’, and; the successful continuation and retention of students, and maintaining of set levels of enrollment as an outcome of student ‘belonging’ (Gallacher, 2014; Thomas, 2012; Woodfield, 2014). Having recently been these students ourselves, we find ourselves skeptical of some of the politicising and policy-making around these areas. Proportional retention and attainment rates are a crude determinant of a successful institution (successful for whom?) (Jones, 2008; Woodfield, 2014), and widening access appears thus far to have made more work for post-1992 universities like QMU – broadening the playing field rather than levelling it (Gallacher, 2014; Ianelli, 2011).

Instead, we see more value in less-statistically-tangible outcomes from work like the Don’t Panic guide. For some time now, Catherine Bovill and colleagues (Bovill, et al., 2011; Bovill & Felten, 2016) have advocated student collaboration in curriculum design, and of students as being ideally positioned in developing learning and teaching approaches. We and our collaborating peers have been lucky to have had the freedom and encouragement from QMU colleagues to exercise our student identity, or ‘student voice’ as active engaged co-creators (Fielding, 2001; Rudduck, 2007) in developing and disseminating the guide. As per the recommendations of Bovill et al. (2011), we recognise that this has all just been a first step – co-created teaching and learning initiatives cannot be simply repeated each year, and will rely on ongoing articulation of a diverse student experience and collective voice.

Since the publication of The Psychologist article (Christie, 2016b), and presenting Don’t Panic at conferences, it has become apparent that several universities across the United Kingdom are lacking a form of support for their transitioning final year students. While there has been a significant amount of attention paid to student transitions, and matters of engagement, these efforts have perhaps been too staff-coordinated and finite in direction in some cases. We propose more dialogue with students themselves, leading to the co-creation of resources and initiatives in learning and teaching, and potentially a more cohesive and mutually-beneficial sense of belonging for both students and staff – thus producing more successful transitions.

We do not suggest that the Don’t Panic guide is the solution, but rather one example of innovation and an attempt to empower the student voice. It simply made good sense for us to do it. While we work on the online embedding of the guide, any interested parties are welcome to contact us to discuss Don’t Panic and/or request the pdf.

What started out as a small, ‘fun’ project between two friends and colleagues has snowballed into something much bigger than either of us were expecting. We have been overwhelmed by the support that QMU has provided us in developing and implementing Don’t Panic within the Division of Psychology & Sociology. Moreover, we are delighted with the positive reception that the guide has received from universities from the UK to Australia. From our experience and that of other students we have spoken to, far too many students struggle on in silence because they think they are the only ones to ‘feel this way’, or that if they do share their problem they will merely be dismissed. While this is never the environment a university would intentionally create for their students, sometimes it is the environment that an extremely stressed year group of students will create for themselves. Our aim was to provide the UG students who came after us with a reassuring ‘you can do this’ and ‘you are not alone’; a support they could re-visit as many times as they needed to throughout their final year.

The guide has also acted as a transitional tool for ourselves – a focal point for how we understand our own careers in HE, traversing the space between student and staff. If nothing else, we anticipate that the most tangible outcome of the Student Transitions Theme will a greater appreciation of what can be achieved through reasonable, collaborative institutional approaches.

Hope Christie gained her BSc (Hons) in Psychology and a Masters in Research from Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh – where she also worked as Psychology Technician. Currently, Hope is in the second year of a Psychology PhD studentship at the University of Bath, funded by the Economic Social Research Council. Email: H.Christie@Bath.ac.uk. @HChristie_psych

Karl Johnson gained his BSc (Hons) in Psychology & Sociology and a Masters in Research from Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh – where he also lectures in Sociology. Currently, Karl is a WISeR Coordinator at the university, concerned with student participation and retention. Email: kjohnson@qmu.ac.uk. @karlpjohnson