Ashley Dennis1,

Lisi Gordon2, Stella Howden1 and Divya Jindal-Snape1

1University of Dundee, UK

2University of St Andrews, UK

Transition has been defined as an “ongoing process that involves moving from one context and set of interpersonal relationships to another” (Jindal-Snape & Reinties, 2016, p. 2). Transition to HE can be seen to be a normative life transition. Within HE contexts, students experience multiple and multi-dimensional transitions impacting on various facets of their lives, and that of significant others (Jindal-Snape, 2012). The changes they experience can include living in a new city, working in a new educational system and/or level of study, understanding and following new regulations and policies, new social and organisational cultures of the institutions, managing daily life issues, leaving old friends and making new friends and new relationships with staff and community. Transitions can be exciting and worrying at the same time (Jindal-Snape, 2016). They can create challenges that yield significant learning opportunities yet occasionally create support needs for students and staff (Briggs, Clark, & Hall, 2012).

In recent years, there has been a growing interest not only in understanding the positive and negative effects of student transitions but developing support strategies to enhance transition experiences within HE contexts (Jindal-Snape & Reinties, 2016). For example, Jindal-Snape and colleagues have developed a body of work exploring international student transitions in HE (Jindal-Snape & Reinties, 2016; Rienties, Hélliot, & Jindal-Snape, 2013; Rienties, Johan, & Jindal-Snape, 2015; Zhou, Jindal-Snape, Topping, & Todman, 2008). International students can face additional challenges such as differences in social and organizational culture and the language, including differences in the academic style (Jindal-Snape & Ingram, 2013; Rienties, Hernandez-Nanclares, Jindal-Snape, & Alcott, 2013). Staff, in turn, have to adjust their teaching and assessment styles to meet the needs and expectations of their international students (Zhou, Topping, & Jindal-Snape, 2011).

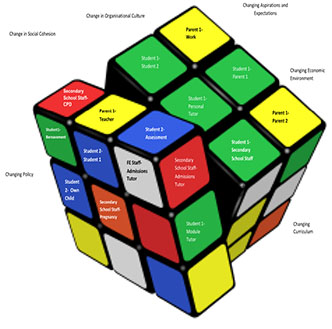

Student transitions have an impact on not only the learner but also on their families, professionals, further and higher-education institutions, and national/international policies (Jindal-Snape & Reinties, 2016). This perspective aligns with the ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which suggests that there are several hierarchical systems (microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem) that impact, and are impacted by, individual experience. Jindal-Snape (2012) developed the Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions (MMT) model (see Figure 1) which incorporates these different ecosystems including the exosystem. Within this model, a change in one aspect can impact several aspects across ecosystems both on an individual and collective level. The HE policy as well as the National policy has to take cognizance of learners’ and significant others’ transitions and support needs (Cairns, 2014; Ota, 2013; Volet & Jones, 2012).

Figure 1: The Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions (MMT) model. Rubik’s Cube® used by permission Rubik’s Brand Ltd. www.rubiks.com

In Scotland, the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA Scotland), has responsibilities for monitoring and advising on standards and quality of HE (QAA Scotland, 2015). As part of this work, they support and manage the Enhancement Theme work, which enables the sector to explore a particular area (theme) i.e. student transitions, aiming to enhance the student learning experience. The themes encourage staff and students to share current good practice and collectively generate ideas and models for innovation in learning and teaching (http://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/). In recent years (2014-2017; three academic years), student transitions have been a key focus of work. We were commissioned by QAA Scotland to evaluate the second year of work on this theme.

The aim of this study was to explore the work that had been achieved in Year 2 of the theme and perceptions of the impact of the theme (for students, staff, and institutions). This study explores these issues within the context of the ecological systems model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), focusing on the meso (i.e. institution level) and macro (i.e. inter-institutional/ sector) as the study methods facilitated data capture of these aspects. Our research questions are listed as follows:

The study took place in Scotland where there are currently 19 HE institutions. These institutions vary widely in size, geographical location and focus. Our aim was to include staff and student participants from all 19 institutions.

We utilised an iterative exploratory research design underpinned by pragmatic research principles (Savin-Baden & Howell Major, 2013). Our mixed-methods data collection occurred through two overlapping phases across three months during 2016. The initial findings from Phase 1 (Consultation Interviews) informed the design of Phase 2 (Questionnaires). Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Dundee Research Ethics Committee (UREC 16018).

Representatives from two management boards (hosted within the QAA) responsible for the strategic oversight and operation of the Student Transitions Enhancement Theme were invited to undertake telephone consultation interviews. Staff from all 19 Scottish HE institutions were invited as well as student representatives. Participants were contacted by email, invited to participate, and provided with an information sheet. Prior to interview, participants returned a consent form and completed a short participant details questionnaire (asking for basic demographic and professional information). An interview topic guide included questions pertaining to participants’ definition of student transitions; Year 2 activities within their institution; evaluation of how things were progressing to date; what priorities were perceived for the final year of the Enhancement Theme and beyond. The semi-structured interviews were audio recorded and lasted between 22 and 41 minutes.

An online questionnaire, was designed through the initial analysis of the Phase 1 interviews. The questionnaire contained a mixture of Likert scale and free-text answers in addition to basic demographic and professional information. A representative from each of the 19 Scottish HE institutions was identified to support dissemination of the questionnaires. Each representative was asked to distribute the questionnaire to up to 20 people (staff, students) who had had a role in the Student Transitions Enhancement Theme yielding a maximum of 380 people. Phase 2 consent was implied through participants’ completion of the online questionnaire.

All data were stored in encrypted files on a university approved shared drive with access limited to the evaluation team. Atlas-ti (version 7) was used to organise and explore patterns in the qualitative data (Interviews/Questionnaire data). Excel was used to organise the quantitative data.

The first and second authors individually listened to a selection of interviews and then negotiated and agreed a thematic framework which was subsequently discussed and confirmed with the wider evaluation team (third and fourth authors). All interviews were then coded by the second author (using Atlas-ti) using the agreed thematic framework. For Phase 2, all questionnaires were uploaded to Atlas-ti and the thematic framework developed in Phase 1 was used to code the qualitative data. For the quantitative data, descriptive statistics (e.g. means) were used to describe the data in tabular and graphical format.

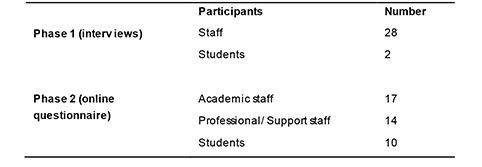

The data presented throughout the results section are combined from Phase 1 and 2 to highlight key findings that arose through both phases. Respondents across both phases were given a participant number (e.g. R10) and are identified broadly by category below (i.e. staff/student). In Phase 1, 18 of the 19 Scottish HE institutions participated. In Phase 2, 14 of the 19 Scottish HE institutions participated (including the institution that did not take part in Phase 1). See Table 1 for participant numbers.

Table 1: Participant numbers

One of the key themes under perceived impact related to definitions of impact. It was felt that there was a need for better definition and agreement of what was meant by impact.

How do you define impact? […] For me it’s about direct impact and it’s about longitudinal impact, so I would say that there has been longitudinal indirect impact over the years (R15: staff)

Furthermore, there was also a general view that it was premature to fully explore the overall educational impact of the Enhancement Theme work.

I think it’s hard to say at the moment, I think it [impact] might be more visible next year than it is right now, I think that all of the work we are doing now will be implemented over the summer (R22: student)

Consensus was that educational impact on student transitions may require several years to be evident. In addition, participants anticipated that the specific impact of Enhancement Theme work on the overall student experience of transitions would be hard to measure and isolate from other institutional and sector-wide activity. Yet the diverse range of theme activities was felt to have enhanced engagement with student transition issues for staff, students and institutionally. Broadly, participants perceived that ‘Student Transitions’ was core business and were enthusiastic about activities locally and sector-wide.

On an institutional level, student and staff participants were generally positive about the activities that were going on in their institution. The theme was seen to be ‘tangible’ and broad creating a wider interest by enabling all staff (e.g. academic, professional and support services) to contextualise and engage with the theme in multiple ways.

[What] I’ve really appreciated about this Enhancement Theme particularly […] it’s captured core business and allowed us to focus on a really fundamental issues which has concerns I think for every member of the university community” (R26: staff)

Student transitions were seen to be a key responsibility for institutions and many described the development of institutional special interest groups and reporting structures to systematically support theme activity. In terms of institution-level impact, because ‘Student Transitions’ had been embedded into core institutional activities, there was expectation that this would lead to institutional level impact. There was also an expectation that concrete and sustainable outputs would be delivered as a result of theme work over time. Participants suggested that the Student Transitions Enhancement Theme had already led to improvement in practices, a better understanding of transitions, an increased awareness and reflection amongst staff of the student transition experience, and a sharing and an emergence of new ideas and developments in relation to the theme.

Theme activities described were diverse. In particular, impact was anticipated at a local level through the outcomes of specific projects. Many had used funds, related to the theme work, to initiate small projects, which was seen as a good way to use the resource and have, in time, direct impact on the student experience. In addition, many participants stated that institutions had provided further resources to support project development and new staff roles. They also described resource development and websites that were used by both staff and students to support student transitions. Institutional events had been well received and were seen as an opportunity to showcase theme-based activities.

Participants highlighted that the (small) size of Scotland made it possible to undertake sector-wide activity and that a good working relationship and an environment of trust between institutions, the QAA and other participating organisations (e.g. Student Partnership in Quality Scotland; Higher Education Academy [HEA]) had been created over the years. Broadly, it was felt that collaborations were in the process of developing in alignment with key goals for the second year of the theme. The activities undertaken in the Theme Leaders Group (TLG) meetings were seen as invaluable for development work. Potential collaborations within and outwith (e.g. schools) the 19 HE institutions had also been identified where multiple institutions were sharing similar theme priorities. Participants also reported an increase in conversations and sharing of best practice through email, meetings, and inter-institutional events.

We’re still struggling with the same things or we could learn from one another so that is something that I’d really say has been a massive positive, sharing the reports as well, I’m constantly emailing my counterparts and know I could pick up the phone to ask them so that strong network is something that’s absolutely key (R12: staff)

Student participants appreciated sector-wide efforts to see things from a student point-of-view and were positive about the Student Network, seeing it as a chance to link in with Enhancement Theme activities across Scotland.

It does feel to be a genuine community there where people do want to try and improve things as a whole. It’s not a […]’us and them’ it’s very much ‘everybody need us to be there’ […] that is particularly unique to the Scottish sector and it is nice to be part of (R21: student)

The educational materials (website, transitions map, new logic model) were also felt to be a helpful springboard for anyone interested in enhancing student transitions and to help explore impact moving forward.

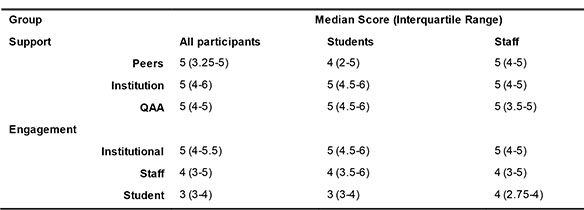

Participants identified a few key facilitators and barriers at sector-wide, inter-institutional, and institutional levels particularly in relation to support, engagement and sustainability. Participants highlighted feeling well supported in their work on the theme on all levels. The questionnaire asked participants to reflect on the support they had received from various groups (peers, institution, QAA) for engaging in their activities related to the Enhancement Themes using a Likert scale from 1-6 (1 = no support, 6 = completely supported). Broadly, perceptions of level of support were positive. Perceptions of engagement during the Year 2 activities through both the interviews and questionnaires were also explored. Within the questionnaire, a Likert scale was used with values from 1-6 (1 = no engagement, 6 = complete engagement), exploring how well they thought the staff, students, and their institution were engaging in the ‘Student Transitions’ Enhancement Theme (See Table 2 for median scores).

Table 2: Staff and student median scores of perceptions of support and engagement

At an institutional and staff level, there was a range of perspectives around staff engagement. Some participants had a positive view of staff engagement.

It [the theme] hits the universities at institutional level but it also filters down to targets that exist at school level and program level. So, if you can do that, then that’s an elegant design in terms of trying to get somebody to engage (R14: staff)

This was particularly evident through staff members’ direct participation in activities (for example as part of the institutional team; or as a project lead). On the other hand, wider institutional awareness was identified as a challenge, particularly in larger or multi-campus institutions. One participant described a ‘language barrier’ between those working on the theme and the wider staff community.

I think it is more challenging to reach those who are not directly involved with transitions projects i.e. the wider academic and professional support staff groups. I am not sure that there is widespread understanding of what the Enhancement Themes are about/purpose (R73: staff)

Participants described ‘pockets of engagement’ and ‘enclaves of practice’ and times when staff may be undertaking student transitions activity but might not recognise this as part of the Enhancement Theme. Participants questioned whether this ‘label’ for activity was important; for some it was, for others not. They also described the need for a continual ‘drip feed’ to raise and maintain the profile of theme activities (for example through reminder emails or newsletters). Being able to resource staff (for example, time to undertake Enhancement Theme projects) was also highlighted as a key challenge. Some participants perceived that the Enhancement Theme work was not seen as relevant by some staff colleagues, with other priorities taking precedence. This could make it difficult to get buy-in. Competing demands included activities aligned to institutional learning and teaching goals and associated measures. Others expressed concern that the success of the Enhancement Theme work across an institution was dependent on the sphere of influence of those involved.

In relation to student engagement, there was a general feeling from the staff participants that students had been well represented and included during the activities, events and projects in multiple ways such as providing feedback, undertaking internships/project leadership roles. Staff were positive about student involvement for the added insight and point-of-view it provided. Student-led projects were seen to be high quality and students had been highly responsive to calls for project proposals or intern applications.

Relatively a lot of the work that we are seeing as part of the theme itself is around the student interns because they’re the ones who are actually focused on this if you like as a job […] all staff are concerned with student transitions and all students are concerned with student transitions (R26: staff)

Student engagement was generally brought about through the Student Associations, the Student Network and specific projects. At institutional level, student involvement was seen to be positive and enabling and that the student experience was taken seriously.

There was acknowledgement that it was difficult to engage the wider student body. Broadly, staff perceived that student engagement was very dependent on the activity and priorities of their local Student Association and that the yearly turn-around of officers meant that staff-student relationships and activity related to the theme could change year-on-year. Some student participants reported that they had found it challenging to drive activity from their perspective. The lack of resource directly allocated for student time meant that there was little incentive to be involved in non-academic credit bearing activity. Student participants stated that outside of student officers there was little engagement and recognition of Enhancement Theme activity. There was also some concern about alignment between staff and student activity. Some described a ‘theory-practice gap’ between talk about student engagement and what actually happened.

Another key challenge that was raised related to sustainability of the theme work. An example of this relates to the sustainability and reach of small projects, where staff and student participants hoped that when projects ended the work would continue, but this was seen to be challenging.

There is a potential downside […] that the good work starts to get “lost” when the theme ends (R67: staff)

As previously mentioned, it was felt that the sector was a good place to work together and that there was an open sharing of ideas and resources. In addition to the funding, participants had found QAA staff to be accessible, involved and communicative with clear directions and deadlines. Furthermore, staff and student participants perceived that they were well supported and were positive about the overall theme leadership, which facilitated engagement and collaboration (see Table 2). As previously discussed, wide community support for the student transition work was apparent and that there was a clear culture of sharing and collaboration.

I think the strengths of the Scottish system and the Enhancement Themes play a big role in […] getting us to work collaboratively rather than competitively in the sector […] it smooths over the different mission groups it doesn’t feel like ‘Oh they’re post-92 [Universities] or they’re Russell Group [Universities]’ (R31: staff)

Several participants had stated that they had come from other UK countries to work in the Scottish sector and had found the ‘market’ more free-flowing and with less of a sense of competition, conducive to sector-wide Enhancement Theme work. This made the exchange of ideas and practices possible and networking activities such as the annual conference and TLG/ Scottish Higher Education Enhancement Committee (SHEEC) meetings were valued.

Although participants expressed enthusiasm and commitment to developing collaborations, they also emphasised that it took time to evolve. There was a general feeling that collaboration was patchy, struggling to gain momentum, and perhaps difficult to sustain or embed. There were also concerns about how much collaboration between the HE institutions should be emphasised.

We are now beginning to overemphasize trying to make people collaborate […] we should have done enough by now. People should be by this stage clear who and when and why they want to collaborate (R04: staff)

Participants stated that whilst activities in TLG meetings related to collaboration generated ideas and intention, once back in their institutions participants found limited opportunity to put ideas into practice, often due to their ‘day job’. Participants also acknowledged that there were a lot of changes occurring sector-wide that posed a challenge for Enhancement Theme work. Participants were acutely aware that agendas such as the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) and Commission on Widening Access could impact on priorities for the future. SHEEC-member participants had noted that Vice-principals for Learning and Teaching were not attending meetings due to wider pressures and what were described as the ‘distractions’ of TEF and diminishing resource. It was thought that a discussion on how these sector changes would impact on Enhancement Theme work in the future was required. At the sector wide level, some students talked about feeling unheard. For instance, there was discussion about the tasks that students had been given as part of the student network feeling ‘tokenistic’ and that there was little opportunity for students to be heard at a more strategic level.

Yes we have engagement at an institutional level but actually at that higher level that strategic level, that’s where there’s a lack of real voice and decision-making I think sometimes that’s timing but I think it also comes down to a how do you make it easier to integrate (R21: student)

Finally, participants expressed that development of new sector-wide resources, in particular, multi-media case studies would be difficult without guidance. In addition, participants identified engagement sector-wide challenging, with the current resources and there was suggestion that metrics on current resource usage (including the transitions map) would help inform how to move forward with engagement. This also linked with concerns about sustainability.

I have concerns that they’ll build this wonderful resource and how will it be used? […] I would hate to see something that was built and then was static and then wasn’t necessarily used beyond the theme (R8: staff)

Furthermore, some participants expressed concern that whilst wide ranging, some areas were being missed out. Examples included discipline specific activity, focus on equality and diversity, international students and a closer look at transitions from an individual perspective. It was suggested that analysing current resources might highlight areas that require further investigation.

This study aimed to explore stakeholders’ perceptions of the impact of the student transitions work as well as the facilitators and barriers for the work. As far as perceived impact, there were a number of key ideas that arose. First, stakeholders questioned how impact is defined. The Theme Leaders Group developed a logic model which outlines the Theme’s objectives, outcomes, outputs and impact indicators to address some of these issues (http://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/docs/documents/student-transitions-logic-model.pdf?sfvrsn=2). At the time of the study, this resource had just been finalised and may not have been as fully utilised by participants though some highlighted this type of resource would be helpful moving forward. Secondly, participants discussed potential difficulties in measuring impact. Many stakeholders felt that it was hard to evidence impact at this stage of the theme, that seeing impact would take time, and that follow-up evaluations of impact would be of value to address this. Relatedly, participants questioned the feasibility of measuring change that could be directly linked to the theme when considering the complexity of Higher Education. These reflections are aligned with broader discussions in the field around defining and measuring impact within HE environments (Parsons, Hill, Holland, & Willis, 2012). The logic model helpfully identifies impact indicators (e.g. evidence of staff and student engagement, comprehensive collection of resources developed for website) which is an important step to avoid underestimating what has been achieved (Parsons, Bloomfield, Burkey, & Holland, 2011). An additional dimension that is apparent is the need for follow up evaluations which is supported by findings and literature in field (Parsons et al., 2011).

Despite the challenges raised in defining and measuring impact, participants described a plethora of ongoing activities and outputs across the sector, inter-institutional and at the institutional level. Some of these activities and outputs were felt to have the potential to create ‘impact’. We would suggest that impact could be meaningfully explored through the lens of the ecological model considering micro, meso, and macrosytem levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). In this evaluation, we focused on the meso and macro levels primarily because of the nature of the study design. This perspective is important as impact at the institutional/inter-institutional/sector level (mesosystem and macrosystem) can support changes on an individual/interpersonal level (microsystem; Gregson et al., 2001).

Participants identified a few key facilitators and barriers at sector-wide, inter-institutional, and institutional levels in relation to themes such as support, engagement, and sustainability. At a sector-wide level, it was felt that the sector was a good place to work and that there was an open sharing of ideas and resources. Participants queried whether certain important areas of student transitions had been missed across the sector, such as discipline specificity and equality and diversity. In addition, there were concerns about the time and space to develop collaborations as well as conversations about definitions of collaborations across the sector. This conversation aligns with broader work in the literature about exploring the depth of organisational relationships (e.g. network vs collaboration) as one way to measure change (Gregson et al., 2001). At an institutional level, there was a range of perspectives around staff and student engagement, where, on one hand, participants rated engagement positively highlighting the relevance of the theme. These discussions link with work suggesting that everyone across the ecological levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) has a role to play in enhancing student belonging, retention and success (Thomas, 2012) which are all linked to student transitions. This also aligns with the broader transitions literature which highlights that transitions are multiple and multi-dimensional (Jindal-Snape, 2012) and therefore impact not only learners but individuals, communities, institutions, and policies that support them (Briggs et al., 2012; Jindal-Snape & Reinties, 2016; Zhou et al., 2011). On the other hand, participants discussed issues around reaching and engaging the wider staff and student community within institutions and that this could sometimes be problematic.

Staff resourcing was also highlighted as a key challenge related to issues such as time. Yet participants broadly agreed that institutions could play a very positive role in providing a systematic approach to developing the theme as well as providing additional resources to support projects. Finally, a key theme that was raised related to sustainability of the work that was being achieved.

We suggest that there may be value in having a dedicated exploration and capture of understandings of impact, in relation to transitions, considering the macro, meso and micro levels. As part of that conversation, an exploration and consideration of the timeframes and resources needed to fully capture this impact is important. Perhaps, for instance, there is value in conducting longitudinal and follow-up evaluations to deepen understanding of the sustainability of activities.

Although there was a lot of positive engagement highlighted across the work on the theme, there were areas for improvement. We recommend considering engagement across the ecological model as a key point of focus for this type of development work. Student engagement was highlighted as a challenge across both institutional and sector wide levels. Considering ways in which students can become meaningfully involved and have a voice in strategic decision making would be of value for this type of project work. Furthermore, we recommend reviewing and expanding ‘pockets of activity’ so that they engage a wider group of people in ways that are sustainable within institutions and also across the sector. Finally, although participants felt that a lot of collaboration as far as idea sharing and discussion was happening across the institutions, this would be another area for consideration. Meaningful collaboration requires sustained working together to support project work, and involves not only collaboration between the professionals from the HE sector, but also with students, families and professionals from other sectors such as FE and schools.

We recommend considering how project work can be strategically aligned with other key sector wide agendas. For instance, developing a mapping exercise that links project work with other key HE agendas such as the Commission on Widening Access may be of value to not only promote projects but to explore issues of sustainability. Relatedly, if there are a series of projects that are ongoing, strategically integrating and aligning the projects may be helpful in creating a long-term narrative, seamlessly transferring the focus of work, as well as supporting sustainability of work long term.

There are a few limitations in this study to address. First it is important to consider the recruitment methods for participants. In Phase 1, we were strategically targeting individuals with leadership roles. In Phase 2, with the support of institutional leads, we were recruiting a broader spectrum of individuals, yet mostly those who were also involved in the theme at an institutional level. Although this was strategically done to gain insight about the theme work from individuals who are involved centrally or peripherally, this means that individuals who were not directly involved in the theme work were not as well represented. Relatedly, although we did have student representation in both Phase 1 and 2, there were fewer students that took part in the study. Future work could explore experiences and perceptions of individuals beyond those who had direct roles in the Enhancement Theme work.

Overall, the findings from this evaluation highlight the complexity of integrating the work of the Enhancement Themes within institutions and across the sector. However, the ‘Student Transitions’ Enhancement Theme has been seen as a key aspect of the work of HE institutions across Scotland which aligns with broader literature calling for HE institutions and policies to consider transitions (Cairns, 2014; Jindal-Snape & Reinties, 2016; Ota, 2013; Volet & Jones, 2012). This evaluation has provided opportunity to explore work that has been achieved during the Theme and stakeholders’ perceptions of how these activities are impacting staff, students, and institutions. Through this evaluation, we have been able to make educational recommendations and highlight lessons learned that can be applied in future Enhancement Theme work but also HE work more broadly.

Ashley Dennis is a lecturer in medical education at the University of Dundee. With a background in both medical education and psychology, Ashley has been involved in a range of research and evaluation including examining cognitive processes in mental health as well as exploring Scottish medical education research priorities.

Lisi Gordon is a teaching fellow in management at the University of St Andrews. Prior to joining the School of Management, Lisi was post-doctoral research fellow for the Scottish Medical Education Research Consortium. A qualified physiotherapist, Lisi has specialised in the study of medical trainees’ transitions and workplace research.

Stella Howden is a senior lecturer in medical education and Associate Dean for Quality and Academic Standards (School of Medicine) with a special interest in curriculum design, evaluation and varied approaches to quality enhancement.

Divya Jindal-Snape is a professor of education, inclusion and life transitions. She has published extensively in the field of transitions including, Multi-dimensional transitions of international students to Higher Education (2016) and A-Z of Transitions (2016).

We would like to acknowledge that this work was funded by QAA Scotland and thank them for their support and encouragement to further disseminate this work.