Sidonie Ecochard and Julia Fotheringham,

Edinburgh Napier University, UK

The concept of transition within the higher education (HE) context relates closely to questions of equality and inclusivity and how the HE sector goes about giving the best chances of success to all students. Indeed, cultural difference theory explains that when the school or HE Institution (HEI) represents a single culture, students raised in different environments will be unfamiliar with the behaviours and attitudes expected of them, leading to underperformance, unless special efforts are made to teach those ‘culturally different’ students (Ecochard, 2015; Eisenhart, 2001).

The student body in the United Kingdom (UK) is increasingly diverse, comprising of ethnic minority students, care leavers, mature students, direct entrants from further education colleges and international students. Currently standing at 22% of the student body in Scotland and 19% in the UK, international students represent a large share of the diversity encountered on British campuses (UK Council for International Student Affairs [UKCISA], 2016). Whilst the literature on transitions makes it clear that many students find the first weeks at a new institution challenging (Kift et al., 2010), research suggests that international students have a particularly hard time (Wu & Hammond, 2011). In addition, these students have become a significant economic driver of HEIs (Hegarty, 2014) so that giving them the best possible experience has become more important than ever in the competition for international students tuition fees.

What are the specific challenges confronting international students undertaking their transition to British HE? What are we doing for these students to adapt to a different academic environment as well as a distinct host nation culture?

International students are defined in this paper as any student who has moved to a different country to study (Biggs, 2003). However, in the context of HE as a ‘capitalistic industry’, international students may sometimes be categorised as per the tuition fees they pay. In the UK, the HE sector may refer to international students as excluding students from the European Union who currently pay the same fees as UK home students.

Transition has been described by Gale and Parker (2014) as “the capability to navigate change” (p. 4). With the concept of consequential transitions, Beach (1999) further proposes that active construction of new knowledge involves the transformation of something which has been learnt elsewhere, resulting in the development of identities and new ways of knowing and of positioning oneself in the world. In the case of international students, the transition undertaken to HEIs includes the additional dimension of change across national borders, so that international students face greater difficulties in their transition to HE than home students (Wu & Hammond, 2011).

Specific concepts are used in the literature to describe trans-national encounters, including acculturation and adjustment. Acculturation was first defined as the phenomenon by which “individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original culture patterns of either or both groups” (Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits, 1936, p. 149). Closely related to the concept of acculturation, adjustment refers to the ability of fitting in the new culture as well as the associated feelings of satisfaction and well-being (Quan, He, & Sloan, 2016). However, Wu and Hammond (2011) explain that in the case of international students, the adjustment is to the international student culture –rather than the host nation culture in general – defined by its use of the English language, participation in the multi-cultural student cohort and a focus on short-term academic goals.

At the other end of the spectrum, the concept of acculturative stress, also called adjustment stress or culture shock, considers the potential negative side effects of international transitions (Bai, 2016). Culture shock is a realisation of the extent of differences between where one comes from and where one now lives and the subsequent loss of all cues on how to behave and orient oneself in daily life situations (Haigh, 2012). Culture shock may result in the degradation of physical, social and mental health, and more particularly anxiety, depression, anger and damage to self-concepts (Bai, 2016; Haigh, 2012; Major, 2005; Wu & Hammond, 2011). In the case of international students, the dissonance is not limited to the sociocultural and cognitive divergences experienced by other international sojourners. It extends to include academic discourse divergence and the resulting pressure and fear of academic failure (Major, 2005).

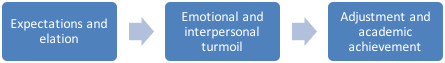

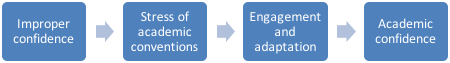

Several models describe the process of adjustment in the literature, depicting it as a learning curve (e. g. U-curve and W-curve). The models consist of a varying number of stages, typically three (Figure 1 and Figure 2) or four (Figure 3), with some cases specific timeframes attributed to the different stages (Quan et al., 2016). Early models looked at international sojourners (Adler, 1975; Gullahorn & Gullahorn, 1963; Lysgaard, 1955; Oberg, 1960; Torbiorn, 1994) and usually started with a ‘positive reaction’ referred to as ‘honeymoon stage’ (Gullahorn & Gullahorn, 1963; Oberg, 1960), ‘adventurous stage’ (Lysgaard, 1955) or ‘fascination stage’ (Torbiorn, 1994). Those models then mapped the evolution from the initial reaction of the international sojourner to the adjustment phase, as a “process of integration over time, or at least a growing familiarity with expectations between a sojourner and the environment” (Wu & Hammond, 2011, p. 426).

More recently, the literature has recognised international students as an acculturating group distinct from other international sojourners, immigrants or refugees for instance (Bai, 2016), as per the additional cultural frameworks to which they have to adjust: the international student culture, the academic culture of the host nation and the institutional culture of the HEI attended (Chilvers, 2016). The significant differences in learning and teaching systems across countries require fast adjustment from international students with the added pressure of academic success (Quan et al., 2016). As a result, international students often experience higher level of acculturative stress than other sojourner groups upon arrival in the host country and models looking at international students specifically may start with a phase of ‘culture shock’ or ‘culture bump’ (Figure 2, Wu & Hammond, 2011). Furthermore, models of international students’ adjustments may include a pre-arrival phase, as is the case in Figure 1 and Figure 3, during which the student is getting ready for the study abroad period (Major, 2005; Quan et al., 2016).

Figure 1: Stages of international students’ adjustment (Major, 2005)

Figure 2: Stages of international students’ adjustment (Wu & Hammond, 2011)

Figure 3: Stages of international students’ adjustment (Quan et al., 2016)

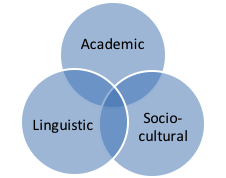

When describing international transitions, the literature makes repetitive use of words and phrases such as ‘challenge’ or ‘challenging’, ‘difficulty’ or ‘difficult’. More specifically, the literature recognises three key challenges or difficulties in the adjustment experienced by international students: language proficiency, academic expectations and socio-cultural integration.

Figure 4: Dimensions of international students’ adjustment

In this paper review, each dimension will be introduced separately at first, before showing relations and intersections as suggested per Figure 4.

The literature pays most attention to the academic challenge faced by international students and describes it in most detail. The rationale underlying this focus relates to the importance of academic success to international students and academic experience as the glue binding together their time abroad (Bai, 2016).

The literature reports extensively on pedagogy being context-dependent and the systemic differences that exist in HEIs from one country to the next (Quan et al., 2016). The academic challenge confronting international students precisely stems from having to understand and adjust to these distinctions. Teaching practices and classroom dynamics – such as interactions between students, and between teacher and student – are very much country specific (Burdett & Crossman, 2012): in the UK for instance, dialogic practices prevail with expectations of students to participate in class (Ramachandran, 2011) through “questioning, criticising, refuting, arguing, debating, and persuading” (Major, 2005, p. 85). Core traditions of learning and teaching also vary greatly across cultures with a particular emphasis in the UK on independent and student-centred learning (Foster, 2011; Quan et al., 2016); core values differ too, including concepts of academic success (Major, 2005). International students often feel confused by the academic language and procedures of their new HEI (Burdett & Crossman, 2012), even more so as understanding the HE jargon of “module, learning outcomes, programme outcomes, core modules, optional modules” is required to select an academic programme (Ramachandran, 2011, p. 207). Unfamiliar assignments and assessment methods can be particularly perplexing to international students (Wu & Hammond, 2011), with essays being a difficult format to grasp and master for international students for example.

Therefore, for students transitioning into UK HEIs from abroad, the academic adjustment can be a difficult one (Bai, 2016), “far more demanding than just displaying linguistic proficiency” (Major, 2005, p. 91). It involves becoming aware of the dissonances mentioned above and adjusting subsequently to the academic expectations of UK HEIs. However, international students will usually reproduce the study strategies used in the home-country initially, based on their prior academic experience (Quan et al., 2016), resulting in poor or disappointing grades despite the efforts invested.

Not all international students experience a linguistic challenge when studying in the UK as some come from English-speaking countries; others will be confronted to it in a lesser extent – as is often the case of students coming from Scandinavian or other Northern European countries (Bell, 2016). However, for most international students, the linguistic dimension of their experience may well be their greatest challenge, as language is the medium to all other aspects of life in the UK (Sawir, 2005 in Burdett & Crossman, 2012).

Language is an important pull factor for international students to come to HEIs in English-speaking countries. Foster (2014) found English proficiency to be “the main attraction for students considering study abroad” by 91% of Brazilian students interviewed (Foster, 2014, p. 151). But upon arrival, international students often realise their linguistic proficiency is insufficient to cope with the demand of an English-speaking environment (Ramachandran, 2011). On the one hand, this relates to the difficulty of communicating with native speakers, in particular the pace of spoken English, the diversity of accents and the unfamiliar use of colloquialisms, idioms and body language (Ramachandran, 2011). On the other, the literature reports that standardised language proficiency tests (Bai, 2016) and traditional grammar-translation teaching methods (Wu & Hammond, 2011) inadequately prepare students for this transition. For instance, Wu & Hammond (2011) write that most international students had never written an assignment in English before their study abroad period, nor had they practiced speaking in English enough. With over half of international students currently coming from Asia, this challenge deserves to be granted particular attention (Bell, 2016).

The socio-cultural dimension of international student adjustment relates to their experience with the host society and population more generally. It is probably the broadest of acculturative challenges and includes many dimensions that one would not necessarily think about unless experienced first-hand. Upon arrival in the UK, international students have to learn to navigate their new city in a short period of time, find accommodation, make a new circle of friends, successfully use the local public transport system, join the healthcare system and adapt to the local food, weather and social conventions (Ramachandran, 2011). Financial pressure can be particularly difficult for international students, and Kwon (2009) identified it as the main source of anxiety in his study conducted in the USA. Ramachandran (2011) for instance reports the unexpected needs to buy four-season clothing in the UK or to go to the Asian restaurant occasionally for a taste of home.

Although the literature usually presents academic, linguistic and socio-cultural integration as separate dimensions, each challenge actually overlaps and influences the others, creating potential virtuous or vicious cycles for international students.

Linguistic proficiency affects international students’ ability to understand lectures, participate in class, to keep up with the reading or to write assignments. As such, language ability plays a crucial role in student academic learning and success (Akanwa, 2015). Moreover, linguistic difficulty obstructs communication with classmates and university staff so that it is harder for international students to ask for the help they need or create friendships with native speakers. It therefore comes as no surprise that language proficiency has been found to be negatively correlated with acculturative stress (Bai, 2016) and feelings of isolation, in class as well as more generally (Kwon, 2009). Consequently, the challenge of language proficiency impacts directly on academic success and socio-cultural integration (Akanwa, 2015; Wu & Hammond, 2011).

Building relationships with host nationals would not only help international students’ socio-cultural integration, but would also improve their language skills and thereby, their academic outcomes too. Additionally, friendships with British nationals would ease the effects of culture shock, as Bai (2016) has found a negative correlation between social support system and acculturative stress. Nevertheless, such friendships often involve drinking, in pubs and restaurants, while many international students are from families with backgrounds that do not allow alcohol or meat (Ramachandran, 2011). Many international students find that such environments interfere with their academic goals, weaken relationships with other students and conflict with their belief systems (Ramachandran, 2011). Even those who would go to the pub report not knowing how to behave or talk appropriately in such situations (Wu & Hammond, 2011). Consequently, international students do not often mingle with home students, in spite of the positive impact it could have on their well-being, language ability and academic learning.

The culture shock experienced by international students, described in the stage-models, is associated with both the scale of change and its pace. Multiple such references are made across the literature:

[I]n a matter of days, international students were expected to negotiate the demands of attending all-day academic orientation sessions, take placement tests, select courses, see advisers, secure housing, and attend to financial transactions in an unfamiliar sociolinguistic and cultural context (Major, 2005, p. 88).

Rather than one particular dimension being the cause of the difficulties experienced by international students, it seems that the core of the challenge is the pace and scale of change, as well as the mutually reinforcing dimensions of adjustment. As culture shock can trigger anxiety, depression, anger, and damage self-concepts, it is crucial for the level of challenge to be appropriate, so as to stretch international students’ self-efficacy while avoiding to damage it (Pickford, 2016). When the demands become overwhelming, perceived support has been found to be key in reducing adjustment stress and its related symptoms (Bai, 2016).

Support to international students refers to all the services provided by HEIs towards student safety and well-being (Forbes-Mewett & Nyland, 2013). The literature on international transitions recognises that the responsibility and efforts for international student engagement and retention are shared between the student and the university (Akanwa, 2015; Kift, Nelson, & Clarke, 2010; Quan et al., 2016). Indeed, in the report Supporting and Enhancing the Experience of International Students in the UK, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA, 2015) reminds us of the principle of equality and diversity in HE and the need to be treating all our students:

[W]ith equal dignity and worth, while also raising aspirations and supporting achievement for people with diverse requirements, entitlements and backgrounds. An inclusive environment for learning anticipates the varied requirements of learners, and aims to ensure that all students have equal access to educational opportunities. Higher education providers, staff and students all have a role in, and responsibility for, promoting equality (QAA, 2015, p. 2).

Given the number of specific challenges confronting international students, HEIs should proactively seek to compensate for students’ different cultural capital so as to increase students’ retention (Kift et al., 2010). In fact, Chilvers (2016) points out that drop-out rates of international students have increased faster than that of home students between 2006/7 and 2010/11. Although international students’ retention rates have improved since, they remain above home-student average across the UK HE sector (Chilvers, 2016). As international students are key economic drivers for universities (Hegarty, 2014), the issue of retention is more important than ever. Support contributes to a positive student experience by creating confidence and reassuring international students (Ramachandran, 2011) while helping them through their acculturation process (Bai, 2016).

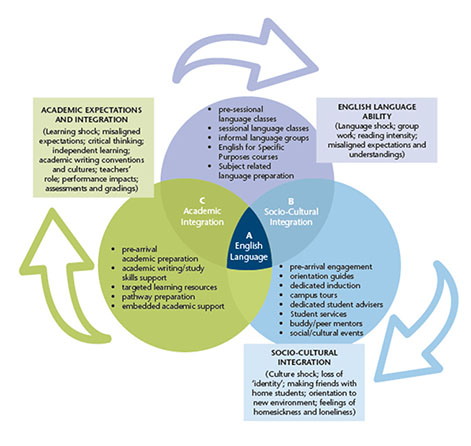

The literature recognises that minimal support for international students should target each of the three main challenges of international students – academic, linguistic and socio-cultural. Figure 5 below describes the key practices in supporting international transitions.

Figure 5: Bell’s (2016) dimensions of international transition support

HE support for international students usually starts with an induction phase during which international students are given details of their programme of study, their institution and the UK more generally, so as to be able to navigate their new environment (Ramachandran, 2011). Induction should tackle academic skills, explaining the academic culture of the UK and pointing to the academic skills support available to international students for their development as independent learners (QAA 2015). For students to be aware of the support on offer across the HEI is particularly important (Kift et al., 2010). Indeed, when such support is not clearly visible, students must search for it by themselves, potentially leading to negative experiences that are hard to dispel subsequently (Ramachandran, 2011).

Universities are also expected to make arrangements for non-native speakers to cope with the linguistic requirements of their programme and be supported in the development of their language proficiency (QAA, 2015). Indeed, language support will enhance international students experience with all aspects of life in the UK, including university life (Burdett & Crossman, 2012; Lin, 2014). The literature is not short of suggestions in terms of formats that language support can take, such as English for Academic Purposes (EAP) workshops or writing seminars (Akanwa, 2015; Bell, 2016). More informal conversation classes are particularly encouraged, as they help build student confidence in expressing themselves in English publicly, while also giving them the opportunity to establish friendships with their conversation partners and to learn about the local culture and local culture of learning (Baird, 2012). Furthermore, the literature recommends developing opportunities for international students’ active engagement in their HE community of practice (Lin, 2014). Chilvers (2016) describes how learning communities support the “academic, social and emotional adjustment to HE” (p. 2) and consequently improve student retention and satisfaction. Indeed, social support systems also lead to reduction of the acculturative stress experienced by international students (Bai, 2016). Universities should be particularly mindful to provide opportunities for relationships between international students, as an effective “survival strategy” and “sources of strength and encouragement” for each other (Akanwa, 2015, p. 280).

A wide range of literature is available on support initiatives and their benefits to the international student experience. However, this model of induction and support to international students is increasingly coming under attack. Inductions tend to be overwhelming for international students, as they are “crammed with verbal, visual, and printed information for immediate and future reference” (Major, 2005, p. 92) ranging from student representation to how disability is defined in the UK (QAA, 2015). Several authors have criticised inductions to international students for happening too late and being too short to address “the breadth of the new skills and awareness that need to be assimilated by the students” (Foster, 2011, p. 4) especially for those who are only staying in the UK for a year. Consequently, Quan et al. (2016) explain that without prior experience of studying in the West, international students find it hard to master Western learning skills fast enough. In addition, support services which are not embedded within the curriculum tend to fall outside of the scope of the student core experience and “appear to be irrelevant to the core business of learning” (Kift et al., 2010, p. 8). Actually, all students are strategic in their attitude to university, and international students more particularly as they are confronted to the additional challenges mentioned above (Bell, 2016).

The concept of internationalisation can present HEIs with an opportunity to reflect on curriculum “relevance, reform and renewal” (Rizvi, 2004, p. 33) and consider a more inclusive approach to student needs than induction and piecemeal support. Indeed, by incorporating an international dimension to the purpose and mode of delivery of HE, internationalisation allows for meaningful interactions “so that cultural differences are understood and respected in ways that enhance social and academic engagement” (Burdett & Crossman, 2012, p. 211) both for home and international students. Internationalisation is a controversial approach to HE, as it is often associated with senior leadership strategies for attracting international students’ fees (Forbes-Mewett & Nyland, 2013; Ramachandran, 2011). Nevertheless, it is beneficial to all students, including home students who have minimum exposure to other cultures (Shanon-Little, 2012). Internationalisation however, starts with the buy-in and cultural awareness of each HE staff (Akanwa, 2015; Bell, 2016; Major, 2005; Ramachandran, 2011).

The models of acculturation in the literature present adjustment as a linear and sequential process experienced by international students towards academic success and fitting-in the international student culture (Bell, 2016; Wu & Hammond, 2011). The international student body however, comprises students of both genders, coming from very different parts of the globe to study on all sorts of programs (UG and PG). Some students bring with them their partners and family; some are native English speakers while others struggle to express themselves. These differences have been found to affect significantly students’ adjustment (Kwon, 2009). In spite of this incredible diversity, international students are usually presented as a homogenous body in the literature, “conceptualised as a straightforward market group” (Taylor & Scurry, 2011, p. 597). Furthermore, some authors acknowledge that acculturation, rather than being sequential and linear, may be experienced as quick back and forth shifts between the different stages so that the stage models “do not really do justice to the complexity of cultural adaptation” (Haigh, 2012, p. 199). Finally, the different models end with international students reaching the mastery or confidence stage. Nevertheless, not all international students successfully acculturate, as shown by their high non-continuation rates. Consequently, ensuring the appropriateness and level of challenge, as well as providing adapted support are crucial to retention and a positive international student experience (Pickford, 2016).

Although the literature acknowledges the cultural benefits of having international students on British campuses (Ramachandran, 2011; Shanon-Little, 2012), a deficit view still transpires through much of the academic literature. The standardised tests of language proficiency have been criticised as inadequate and the test scores required for admission have been described as too low (Bai, 2016). The language teaching international students receive pre-departure has also been decried as focusing too much on grammar or translation and not enough on the real-life situations that students will have to face (Wu & Hammond, 2011); moreover, language teaching is not usually done by native English speakers (Ramachandran, 2011).

However, it would be unrealistic to expect international students to arrive in the UK speaking fluent English, with the pre-existing knowledge of accents and idioms necessary for easy communication with native speakers. Such an expectation would be underestimating the difficulties and time commitment that language learning entails, especially for those students who come from non-alphabetic language systems. Immersing oneself in a foreign language by moving abroad is the best way to drastically improve one’s linguistic skills, and this is why many international students decide to come to English-speaking countries to study (Foster, 2014). Wu and Hammond (2011) report that by the third term, most students’ English fluency had really progressed in academic and social settings, in spite of remaining difficulties towards completing some academic tasks. While HEIs have a responsibility in setting up arrangements for non-native speakers to develop their linguistic proficiency and cope with the demands of their programme (QAA, 2015), HE staff can also do their part by understanding the true scale of the linguistic challenge and being mindful of how they express themselves. Simple steps such as speaking slowly while facing the students, using common words and visual help, and offering to repeat as many times as necessary will go a long way towards supporting the understanding of international students in lectures and being able to complete the assignments.

Finally, it may be unrealistic to expect of all international students to behave in the classroom and perform in tests in the same way as home students do. The learning experience of international students in the UK extend much further than improved linguistic proficiency, new academic skills and subject content of their programme. Among others, adjusting to life and study abroad require tremendous effort and talent. It permanently affects the ‘habits of expectation’, “these prisms and lenses, constructed in our biographies, largely for most of us through participation in the norms and rituals of our socio-cultural world, [that] frame how we read and interpret the goings on along our lifeworld horizons” (Killick, 2012, p. 183). It is about forming cosmopolitan and multi-lingual citizens.

This literature review aims to raise awareness of the potential challenges confronting international students as they transition on British campuses and programmes. A number of staged-model have attempted to describe the experiences of international students as they undertake this process of transition. However, the interactions and intersections between the multiple dimensions of the international transition challenge, along with the distinct profiles of international students themselves, mean that international transitions are characterised primarily by diversity in terms of experiences and needs. HEIs often use such diversity as a marketing tool and value it for driving forward institutional capital on economic and cultural levels (Taylor & Scurry, 2011). Meanwhile, the question of who takes responsibility for this diversity remains unanswered: international students are often presented as deficit and failing, especially linguistically, and expected to change and improve to fit in within the existing institutional culture (Taylor & Scurry, 2011). As such, international transitions highlight persistent inequalities and power dynamics in the HE sector, as well as opportunities for furthering current institutional conceptualisations of ‘learning’ and ‘student experience’.

Sidonie Ecochard works at the Department of Learning and Teaching Enhancement at Edinburgh Napier University. She is involved in Edinburgh Napier University’s answer to the QAA (Scotland) Enhancement Theme Student Transition, and conducts initiatives and research on international transitions, internationalisation of the curriculum and the nexus culture-learning.

Julia Fotheringham is a Senior Teaching Fellow and Senior Fellow of the HEA. She is the Edinburgh Napier University institutional theme lead for the QAA Enhancement Theme working on various strands of research activity relating to student transitions. She is Programme Leader for the PG Cert in Teaching and Learning in Higher Education and Module Leader on the MSc Blended and Online Education (BOE).