Rachael Powella, Panos Vlachopoulosb and Rachel Shawc

University of Manchestera, Macquarie Universityb and Aston Universityc

This paper describes the development and evaluation of a reflective log assignment intended to enhance depth of learning on a taught postgraduate psychology course. Students on two programmes (Master of Science (MSc) in Health Psychology and MSc Psychology of Health) took the taught module Illness Processes and Behaviour. This module contained an extended essay assignment through which in-depth knowledge and critical ability were effectively assessed, but which did not encourage students to reflect on the material they were learning or to relate it to their own experience. Reflective writing is expected to help a student to develop a deep learning style, with the goal of understanding the material rather than memorising facts (Biggs & Tang, 2007; Moon, 1999a). We therefore sought to develop and evaluate an assignment that would help students to actively participate in their learning by spending time reflecting on material covered and to encourage them to integrate this material into their knowledge base.

Ryan (2011) notes: ‘the social purpose of academic reflection is to transform practice in some way, whether it is the practice of learning or the practice of the discipline or the profession’ (p. 103). Much literature considers reflection with people in practitioner, or trainee-practitioner roles whereas, in the academic learning context, reflection on the practice of learning through class-based activities and reading is of importance – improving students’ thinking rather than focusing on professional behaviour. The term ‘reflection’ has been defined in a number of ways (see Mann, Gordon, & MacLeod, 2009; Moon, 1999b for reviews of this literature). Moon (1999a, p. 23) gives a fairly general definition: ‘a form of mental processing with a purpose and/or anticipated outcome that is applied to relatively complex or unstructured ideas for which there is not an obvious solution’. Although generic, this definition is clarified later: ‘By reflective thinking, we mean mental activities such as relating, experimenting, exploring, reinterpreting from different points of view or within different contextual factors, theorizing and linking theory and practice’ (p. 33). Thus, drawing on this definition, reflection is a process of not simply recalling events or material but of metacognition – thinking about the thoughts and knowledge given by an experience, re-organising those thoughts and integrating those thoughts and knowledge with existing cognitive frameworks. The notion of ‘metacognition’ has also been associated with the idea of professional wisdom, and reflective writing has been shown to improve professional decision making (Higgs, 2012), an important ability for postgraduate students whose next destination could be a health care setting. Reflective logs therefore should require an individual to not just describe experiences but to critically re-consider those experiences and, in so doing, achieve a higher level of understanding. As stated by Moon (1999a, p. 18), ‘Reflective writing could be likened to using the page as a meeting place in which ideas can intermingle and, in developing, give rise to new ideas for new learning’. It is recognised that it is beneficial to help students to develop deep learning styles, where they seek a meaningful understanding of material, as opposed to a more superficial surface approach where students focus on meeting course requirements (Biggs & Tang, 2007). Moon (1999a) reasons that reflection should help a student to develop a deep learning style, as they ‘rethink’ or ‘reflect’ on material encountered; reflection is ‘seen as a form of ‘cognitive housekeeping’ that facilitates the reorganization of ideas that occurs in deep but not surface learning’ (Moon, 1999a, p. 26).

Many recent papers continue to advocate the importance of reflection in education (Hargreaves, 2016) and in professional learning (Helyer, 2015). When used effectively and purposefully reflection facilitates ongoing personal and professional learning, and creates and develops practitioners capable of demonstrating their progression towards achieving discipline-specific professional capabilities. Many professional accreditation bodies place reflection as one of their expected professional capabilities for their members. For example, the General Medical Council in the UK expects doctors to ‘regularly reflect on your own performance, your professional values and your contribution to any teams in which you work’ (General Medical Council, 2012, p. 15). Reflective writing, therefore, is seen as an important skill for students to master before they enter their professional lives. Reflection is particularly seen as relevant by professional psychological societies, such as the British Psychological Society (BPS). For students on our MSc Health Psychology course, their programme was accredited by the British Psychological Society (BPS) as Stage 1 in the training to become a Health Psychologist. The current syllabus highlights the importance of reflection as a core skill for students to gain (BPS, 2015). Students who continue to Stage 2, a doctoral-level professional qualification, are required to demonstrate continued reflection on their development as they gain the required professional competencies (BPS, 2015).

Requiring students to write a log is expected to facilitate them in actively creating their own learning experiences and to encourage deep learning processes through a range of mechanisms: students are obliged to find the time and focus to reflect on material covered; organisation and clarification of thoughts is encouraged; students are more likely to use a deep learning approach when encountering material in anticipation of the need to reflect on material; reflection allows ideas to be noted which may be useful to the student later; opportunities arise for teachers to identify cases of misunderstanding and so correct any such misunderstandings (Moon, 1999a).

There is some evidence that reflective tasks are effective in meeting the goals of developing thinking and learning. Sharma and Xie (2008) conducted semi-structured interviews with doctoral students who used reflective weblogs. Students felt that the logs were helpful in developing thinking and learning, for example by necessitating them to engage more with reading materials, to evaluate their reading critically and by creating the space for them to organise their thinking and bring thoughts together. Reflective writing has also been perceived to support the acquisition of critical skills by nurses completing a professional course (Jasper, 1999).

Reflective writing is, therefore, a task with potential to address the needs of our taught postgraduate students. We wished to develop, and evaluate, a reflective log as an assignment for the MSc Health Psychology/Psychology of Health programmes; this assignment is described below.

The reflective log was introduced for the intake 2011/2012. Students were asked to make entries as they progressed through the module, noting key learning points from lectures, seminars and reading and reflecting on their own learning experience. Like King and LaRocco (2006), we used the electronic online journal facility on Blackboard, a virtual learning environment, so that students could update their logs regularly, with tutors observing logs from time to time. Students were informed that logs would be viewed every few weeks to encourage them to keep logs up-to-date and to provide opportunities for feedback.

The course structure was that each topic ‘session’ consisted of a lecture followed by a seminar the following week. Students were instructed to write a minimum of 200 words reflecting on each session, and were encouraged to reflect about once a week. A maximum entry length was not imposed so that students could explore their reflective writing to a length they felt useful, and students could structure the text however they wished. Reflective logs were graded ‘pass’ (has completed logs and has demonstrated engagement in course material) or ‘fail’ (has not met these criteria) because reflective writing was a new skill to these students and the assignment was designed to be helpful in their learning rather than adding to coursework burden. Also, the influence of assessment on students’ motivation to engage and on the quality of reflection is unclear. It has been argued that ‘raw’ reflective writing should not be assessed as it acts as an aid to learning, rather than demonstrating the outcome of learning, so marking a student’s reflections would be akin to grading notes for an essay (Moon, 2004), and careful thought is advised when considering assessment of reflection (Coulson & Harvey, 2013). Therefore logs were not credit-bearing (which would require the award of a grade) but students were required to engage with the process and to ‘pass’ the logs in order to pass the module.

Advice on how to structure reflective logs to support students to successfully enhance learning at a deep level includes:

Make the purpose of the journal clear to students (Dyment & O’Connell, 2010; Moon, 1999b)

Construct clear questions for students to answer (Dunlap, 2006), prompts (Dyment & O’Connell, 2010) or suggest exercises such as reflecting on reading material (Moon, 1999b)

Teach students about what it means to write at different levels (e.g. deep as opposed to surface-level approaches), and explain models or frameworks that help students to understand what is required to write at the required level (Dyment & O’Connell, 2010)

Suggest students note down thoughts in class to address in their reflective log (Moon, 1999b)

Provide feedback (Dyment & OConnell, 2010)

The purpose of the reflective log, and the aims of reflection, were made clear to students through a handout and a class presentation. Writing was facilitated by methods including suggesting questions students might want to address, for example, ‘What was the most important thing you learnt this week? Why was it important? How/why might it affect future research/practice?’; ‘reflect on points you found difficult – how might you address these difficulties?’. Students were shown models of learning levels, with indication of what would be seen as taking a ‘deep’ as opposed to a ‘surface’ approach to learning (Entwistle & Peterson, 2004). Students were advised to note down their thoughts in class, to facilitate the later writing of their logs. Feedback was provided every few weeks by the course lead (RP), on two occasions prior to the final submission of logs.

It was possible that students might reveal personal information in their reflective logs. It was therefore made clear to students prior to their commencing the logs that the course lead would view the logs regularly, and would also provide feedback at the end of the course. Students were aware that, as per standard practice for assignments, other teaching staff could view the logs, for example for moderation purposes. Other students were not able to view the contents of an individual’s logs. Thus, it was expected that students would not include material that they would be uncomfortable for teaching staff to view.

We wished to evaluate the log in terms of whether it met its pedagogical aims and to also understand how the students found carrying out the assignment. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the extent to which the logs were successful in encouraging students to actively engage in course material and to explore students’ experience of completing the logs.

Study 1: Was the reflective log assignment effective in encouraging active engagement with course material?

Study 2: How did students find the experience of completing logs? In particular, how valuable were the logs perceived to be in supporting students’ learning?

Study 1: Analysis of log content to assess the types of entries posted by students (in particular, to assess whether entries were descriptive or reflective).

Study 2: Qualitative focus group study to assess the student experience of completing the reflective log assignment.

Ethical approval was provided by the University Centre for Learning Innovation and Professional Practice Ethics Committee. The main ethical issue was considered to be that the same person (RP) was both the researcher and course convenor, so there was risk that students may have felt coerced into taking part. To minimise this risk, it was clearly stated on the information sheet that participation was voluntary and would not affect course marks or how they were treated as students. It was also clear that they could consent to participate in either study 1, study 2, both or neither. As four students did not consent to take part in study 1, and nine did not consent to take part in study 2, it would seem that this reassurance was effective, and students did not feel coerced. To maintain confidentiality, all data were anonymised prior to analysis, and quotes presented in this report were carefully selected to ensure that they would not identify the participant. Participants were informed that members of health psychology staff in addition to RP would view anonymised data in order to validate the analysis processes.

Participants were drawn from the postgraduate psychology students taking the module Illness Processes and Behaviour at Aston University, UK. Seventeen students took this course and were required to complete reflective logs as a course requirement. All students were provided with information sheets which explained the purpose and procedure of both studies 1 and 2, and made it clear that taking part in these studies, whether by allowing their logs to be analysed for research, or by taking part in the focus groups, was voluntary. Participation took place on an opt-in basis: students who wished to take part in the studies completed consent forms indicating they understood the purpose of each study and that they were happy to take part. Throughout, it was made clear that participation in the research was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the research at any time, without giving a reason. It was also made clear to students that, should they choose not to take part, no sanctions would be taken against them, their relationship with teaching staff would not be affected, and the research process would not affect marking of the assignment.

Completed reflective logs were saved into Word and analysed using content analysis. The coding scheme is presented in Table 1. The sentence was chosen as the unit of analysis, with each sentence being coded for content relevant to reflection.

|

Rating |

Relevance of content to reflection goal |

|

0 |

Not relevant to course material |

|

1 |

Relevant to course material, surface level content only. These entries would typically be descriptive – e.g. describing material covered in class, rather than demonstrating that they are thinking about the material presented. |

|

2 |

Relevant, includes deep level content – demonstrating thinking about and reflecting on course material/requirements/experience of the class. |

Table 1: Guide for content analysis

Determining whether the content contained ‘surface’ as opposed to ‘deep’ level content was central to the coding scheme. Distinguishing between levels was conducted with reference to Entwistle and Peterson (2004, p. 415). A ‘deep approach’ is considered to be aimed at ‘seeking meaning…to understand ideas for yourself’ and includes processes such as ‘relating ideas to previous knowledge and experience’; ‘looking for patterns and underlying principles’; ‘checking evidence and relating it to conclusions’; ‘examining logic and argument cautiously and critically’; ‘monitoring understanding as learning progresses’; ‘engaging with ideas and enjoying intellectual challenge’.

Entwistle and Peterson (2004, p. 415) consider a ‘surface approach’ to be about ‘reproducing content…to cope with course requirements’. It would be detected by features including ‘treating the course as unrelated bits of knowledge’; ‘routinely memorising facts and carrying out procedures’; ‘focusing narrowly on the minimum syllabus requirements’; ‘seeing little value or meaning in either the course or the tasks set’; ‘studying without reflecting on either purpose or strategy’; ‘feeling undue pressure and anxiety about work’.

The reliability of the coding scheme was piloted on a randomly selected (using computer-generated random numbers) sub-sample of data. Two sentences were selected from each participant. The first and third authors independently coded each sentence. Agreement of reflective content was low, with agreement reached on only 15 of 26 sentences (57%). The raters met and discussed ratings until agreement was reached on each item.

The full data set contained 1853 sentences; 95 (5%) were randomly selected for double-coding, meeting Neuendorf’s (2002) requirements. Reliability for these sentences was assessed using Krippendorff’s _ (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007; Krippendorff, 2004).

Focus groups were conducted using a topic guide covering: how students found the experience of completing the logs; how they felt completing the logs affected their learning process; how valuable they found completing the logs; their thoughts about the assessment strategy. Questions were deliberately open-ended to ensure that participants were able to identify and discuss issues that they considered important.

Two focus groups and one individual interview were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were analysed thematically using a Framework approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006; itchie & Spencer, 1994). Transcripts were read multiple times and annotated. Emerging themes were used to generate a coding frame and line-by-line coding was conducted. A chart was used to assist cross-case analyses; this chart was used to produce a written analysis of the data, with constant referral back to transcripts to ensure that the analysis was grounded in the discussion context.

Thirteen students consented to their reflective logs being analysed (76.5%). The mean age of participants was 24.5 years (range 21 to 31). Most (9) were female. Eight participants were British (of various ethnicities).

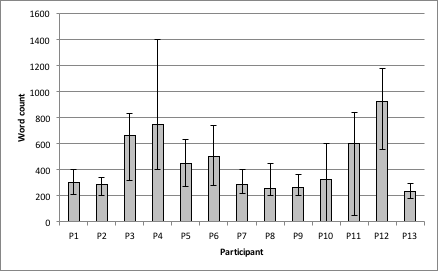

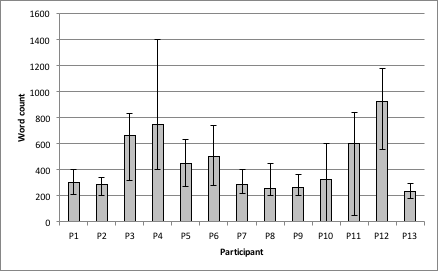

The mean lengths of students’ log entries are displayed in Figure 1. Whilst some students (e.g. P8, P13) appear to have just written the minimum 200 words per session, others have clearly taken to the task, writing well over the required amount for each entry.

Figure 1: Mean number of words written for each student over 8 sessions. Error bars indicate the range of entry length.

The first author coded all 1853 sentences; 95 sentences were also independently coded by the third author. Reliability data were obtained for 94 items; one was missing because the second rater was uncertain how to rate it. Despite the pilot exercise, reliability was low. Agreement was reached for 61.7% of items, yielding Krippendorff’s _=0.20 (95% CI 0.002, 0.40, using 10,000 bootstrap samples). The third author took a narrower view of what constitutes ‘reflection’ than did the first author (Table 2). For the present analysis, data are presented as rated by the first author, with the assumption that the ratings are internally consistent – i.e. we assumed that the first author was rating each sentence consistently, in a similar way, even though the rating approach of the first author differed from the third author.

|

Rating |

Number (%) ratings given by Rater 1 (the first author) |

Number (%) ratings given by Rater 2 (the third author) |

|

|

0 (irrelevant) |

1 (1.1%) |

8 (8.5%) |

|

|

1 (relevant but surface level/descriptive) |

17 (18.1%) |

38 (40.4%) |

|

|

2 (relevant, indicating reflection/deeper learning) |

76 (80.9%) |

48 (51.1%) |

|

Table 2: Frequency/proportion of reflection ratings given by

Rater 1 and Rater 2 for the 94 items with dual ratings.

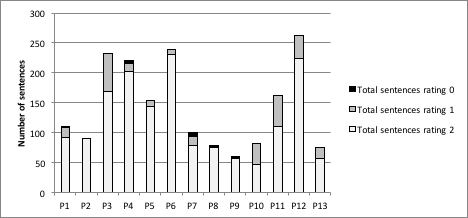

Figure 2 shows the number of sentences demonstrating reflection for each participant (rating 2). While many students have a quantity of sentences at a purely ‘descriptive’ level (rating 1), some (e.g. P3) also have a very high number of reflection sentences.

Figure 2: The number of sentences given ratings 0 (irrelevant), 1 (relevant, surface/descriptive) and 2 (relevant, showing reflection).

Eight students volunteered to take part in this study. There were two focus groups (FG1: V1, V2, V3, V4; FG2: V5, V6, V7) and one participant (V8) was interviewed alone due to practical circumstances. The mean age was 24.4 years (range 22 to 31); most (7) were female. Six participants were British (of various ethnicities). Discussions lasted 25, 49 and 45 minutes for FG1, FG2 and the solo interview respectively.

Participants were mainly positive about the experience of completing the logs; a number of students found them enjoyable or interesting. For some, writing the log appeared to have some psychological benefit. Writing was described as relaxing or ‘therapeutic’:

it’s quite nice just like, in a way quite therapeutic when you can just write anything which comes to mind and just thinking about it in your own head (V6).

The experience seemed to be greatly affected by prior experience of writing logs and the topics under discussion. Many students had not encountered a reflective log assignment before and reported initial uncertainty:

I thought it was quite daunting as well at the beginning because I’d never done anything like that in school or my uni before so but yeah, it’s quite easy once you get into it (V2).

Although common, this initial uncertainty often gave way to confidence as the log progressed.

For many students, the extent to which they enjoyed writing a log, and the ease of writing, depended on the extent to which they found a particular class’s content engaging:

depending on what you’re reflecting on and how you feel about it will definitely reflect how, how you reflect on it and then how you feel about that particular week (V5).

If something interested me more it was really easy and I could find myself typing loads and sometimes if it wasn’t something that I found as interesting I found it more difficult (V6).

If the course material struck a chord with the student, if it was a topic of particular interest or it resonated with their own experience, the process of reflecting on it became both easier and more enjoyable.

A range of positive impacts were identified by participants; benefits also related to how a student chose to use their log. Some students reported that the process of having to look over notes helped them to retain course material, which for V1 was a valuable experience:

when you come back from the lectures…you don’t really ever think about it whereas with this you come back and you have to actually think about it and then, when I’m on the phone and I’m talking to my mum… I could actually say oh well, this was the kind of thing that you learned whereas beforehand I don’t really think I was really saying anything about it because you just kind of sit in the lecture and you take notes and then that’s it (V1).

One participant also looked over previous logs, using the process to review material covered previously:

I found that each week that I was going back to upload a new log I was re-reading over what I’d already posted and refreshing like what I’d posted on, and it you know kind of encourages you to like relook at those you’re not perhaps so interested in so that you kind of still trying to take in a little bit of knowledge even if you’re not completely bowled over by it (V5).

This extract demonstrates that writing the log also benefited students’ understanding of areas which did not pique their interest. In one focus group, the interviewer specifically queried whether having to write the log might have helped students to focus on less interesting areas, and V6 responded:

I definitely think like some areas which I found quite difficult to get to grips with … it did sort of like force me, OK, to revisit it, look over bits which I did find more difficult and cos sometimes they went hand in hand with the topics I wouldn’t be as interested in, probably because I find them more difficult, … it’s a positive from it because you are looking through topics which you found difficult and trying to make sense of them in your head

It therefore appears that the logs were helpful in developing a deeper level of learning.

This was also the case for V8, a student who took to the reflective writing process well; he enjoyed being given space for his thoughts – ‘I just kind of saw it as an advantage to think out loud’. V8 also used the logs to express and experiment with thoughts, which was particularly valuable because of the feedback mechanism:

it kind of turned from a think aloud process to a, also, if there’s something you’re not sure about, maybe this might be a place just to throw it in the air.

This engagement in reflective writing had a positive learning impact, leading to deeper processing and new ways of considering the course material:

I thought it was a very very intelligent way of making a course a little bit richer and a little bit deeper. The learning process expanded because of the log in my opinion (V8).

The log also affected V5’s approach to learning, encouraging wider reading:

for the topics I was more interested in I found myself looking into other areas as well and like looking more into the directed reading and sort of references that were, that were provided for us…just to see if there was anything else that interested me.

Some embraced the logs as a tool for managing information – V3 chose to use them to actively organise course material, in particular to summarise reading ‘so it helped me with my seminar work as well’. While this meant that the log entry would contain substantial descriptive elements (as evidenced in Figure 2: V3 was P3 in the log content analysis), this was perceived by V3 as beneficial in supporting her learning; Figure 2 shows that P3/V3 also entered significant reflective content.

A discussion arose in the first focus group about the opportunity provided by the logs to share thoughts and opinions that students did not feel able to express openly in class either out of lack of confidence or concern about self-disclosure:

V3: I think it’s a good chance to express your own opinion as well because you might just go to the lecture and learn what you’ve learned…in the log you can reflect and then give your own opinion which gives people a chance to say what they actually want to say

Interviewer: Oh, OK. Does that, is that because in the classroom, in a session itself, is it quite hard sometimes to voice that kind of opinion or?

V3: Yeah, like for people who doesn’t like to voice their opinion in front of everyone they can do it in the reflective log

…

V4: Yeah, I find that definitely, cos I’m not very vocal in class but in my reflective log I really enjoyed kind of like giving my little contribution [laughter]

V1: …if someone says something you’re kind of scared to add in in case you’re wrong, and then you just make a complete fool of yourself whereas in this it’s just you that’s putting your own thoughts down and no one else can say ‘yeah, well, that’s wrong’

V4: Especially if it’s like your personal experience as well, erm, that you might not necessarily want to share with the whole class…

This interchange was revelatory in that it demonstrated that students who were quiet in class were engaged and had thoughts which they were keen to express, just not in a public setting.

Some students saw the log as beneficial not only in how it affected the learning of course material, but also as a skill in itself. Some of these students hoped to practise professionally in clinical contexts and the idea of being a reflective practitioner was therefore relevant, as expressed by V5:

you’re not only encouraging people to learn more on top of what they’re taught in lectures but you’re also, as we’ve been taught like so far during the course as health psychologists you have to learn how to be reflective.

These data demonstrate that completing the logs was perceived to have positive impacts on students’ learning in an unexpectedly broad range of ways.

The reflective log task does not seem to have been perceived as excessively burdensome - ‘I think that there’s only like, there is only 200 words isn’t it so it wasn’t a big ask’ (V4). Typically, students seemed to spend about half an hour on an entry, although this depended on the stage in the course and also the level of interest in the topic. Generally, students reported that the task took more time and effort for early entries, when they were unsure of the process - ‘maybe by the end about half an hour because it just flowed more easily than at the beginning’ (V2). Students tended to find the task easier if they completed it soon after a taught session:

If I could like remember it freshly and I didn’t really need to look for anything and I had opinions and things that I did naturally want to reflect on, ways like the topic actually fitted into like my life and past experiences I found it really easy and I could get a lot of words done in like twenty minutes (V6).

In this extract it is also clear that reflection came more readily if the content resonated with students’ interest or experience. This did not always lead to the log being quicker to complete, however – for some, this led to their engaging more with the log writing – ‘I could like spend longer on the ones that I was more interested in cos I had more to say’ (V4). Comparisons were drawn between this assignment and others; the log was viewed as a very different piece of work, with more freedom to just write rather than to give the level of attention to detail required of more formal academic assignments:

in our last week when we had our essay in I was actually looking forward to doing the reflectives to have a break from the essay [laughter] it was quite nice, yeah, because I could just write, you know, without the reading… and all that kind of stuff (V2).

The first focus group reached consensus that the log should be credit bearing but they did not want it to be given a grade (other than pass/fail); otherwise they would have written differently, with less freedom:

I thought about it and yeah it would be a nice thing to feel that the essay is not such a heavy weight but then when I think about the log if, if it’s a graded piece of work it wouldn’t, I might not feel the same way when I write it (V3).

This view was shared by V8:

I would like to attach a pass/fail percentage to it, just so that people feel rewarded for it…If it’s going to be actually graded, leave it the way it is…it will change everything.

While these students wanted to receive credit for the log, aspects of the assignment that they valued would be lost if a grading structure were introduced.

There was no consensus in the second focus group; indeed, a lively discussion on the issue of assessment took place, with each participant taking a different stand. V5 shared the opinion of previous students:

this is what we’re being taught to be as health psychologists so you want to know that your reflective log counts for something (V5).

However, V5 did not feel that it should be given a grade because the logs would differ so much between individuals:

I don’t think you can do it any differently cos it’s so like personal to, you can’t, you can’t really mark it on like a pass, merit or distinction basis (V5).

In contrast, based on experience at undergraduate level when a reflective assignment had been graded, V7 felt that receiving a grade was beneficial:

I think it’s good to, it felt good then, probably because I got a good grade but [laughter] about that it got marked in a way that just measured your… ability to reflect rather than what you were reflecting on (V7).

Views on types of assessment were varied but accounts suggested support for assessment per se.

Study 1 found that students engaged in the log task to varying degrees, with some completing logs of the minimum length to pass whereas others clearly took to the logs and wrote much more than the minimum required. The content analysis suggested that, not only were students writing about the course, but they were largely doing so reflectively.

The focus group data suggested that students found the reflective logs enjoyable and interesting. Participants valued positive impacts on their learning including improved retention, being forced to grapple with difficult-to-understand topics, and having the space to explore thoughts. Many participants found it useful to make notes in the lecture when issues arose that they would like to reflect on, suggesting that the logs may have enhanced active attention to, and processing of, material in taught classes. More timid students used the logs as an outlet to express opinions that they felt unable to voice in class, extending their participation in written form. The assignment was not considered particularly burdensome, especially if completed soon after a class or on a topic of high interest.

In focus group discussions, some students reported that they were processing taught material more deeply. Similarly, students who completed logs reported that the logs helped them to develop thinking and learning in Sharma and Xie’s study (2008). However, both Sharma and Xie’s study and our focus group discussions relied on students’ self-report of their experiences – not only were participants aware of the researcher’s goals in implementing the log, but the extent to which they perceived themselves to be processing information more deeply may not reflect actual depth of processing. Nevertheless, the analysis of log content suggests that students did devote a reasonable proportion of their logs to reflective, deep processing.

Many of our students wished that the assignment could be awarded credits, but did not want it graded. This is consistent with the experiences of Creme (2005) who found that students either felt that their effort should be rewarded or that it is not possible to award a mark to something that is ‘in my head’. Our students sought a compromise where their work would count towards their overall degree grades, i.e. represented a proportion of credits within the module but without it being given a grade. The desire for credit suggests that the assessment strategy deserves further consideration. Cowan and Cherry (2012) recommended that students should be involved in assessing reflection through self- or peer-assessment. There is growing consensus that assessment motivates students to engage with reflection, and provides them with feedback, which requires assessment criteria that are clearly understood, if not negotiated, by the students and which cover both the process of reflection and its product. For example, Pavlovich (2007) explored the design and assessment of reflective journals and concluded that assessment of reflective writing poses challenges in terms of design and grading but it is an important factor for motivating students to reflect. Vlachopoulos & Wheeler (2013) reported that having clear assessment criteria and rubrics improve the focus of the reflection and facilitate deeper reflection. Involving students in assessment may help to ensure that aspects of the log that were welcomed by our participants would not be lost. There is the additional benefit that the processes of considering assessment criteria and involvement with self-assessing reflective writing would themselves require students to reflect on the learning process. However, given the difficulties we found in agreeing on quite basic ratings for reflective content, a tighter log structure and very clear information regarding marking criteria would be needed for marking to be reliable.

A limitation was the disappointing inter-rater reliability, despite piloting, of the content analysis rating scheme. One possible reason for this is that the third author was not present at the taught sessions – all sessions were taught by the first author. The first author therefore knew when a student was simply describing an event from class and when they were giving their own thoughts; this would not always have been apparent to the third author. This could explain why the first author was more likely to rate sentences as including reflection than the third author.

The researcher facilitating the focus groups (the first author) was also the course convenor. As the convenor had explained to students, during the course, what we hoped the reflective log assignment would achieve, this knowledge, combined with the power differential between convenor and students, may have influenced students’ responses. The focus group study findings should be interpreted with this staff-student relationship in mind.

The reflective logs fulfilled their purpose of encouraging students to reflect on the course material. Students varied in their engagement with the logs, but overall, students seemed to find it a positive, enjoyable assignment, and used it to aid retention, facilitate deeper thinking, to support further reading and to voice opinions. The formative feedback was seen as helpful and encouraging. Many participants would have preferred the assignment to be credit-bearing but without receiving an actual mark as this would change the way they completed it. Further thought is needed as to how we assess and ‘count’ log performance; it would be valuable to assess the impact of any changes with further analysis of log contents and student feedback.

Rachael Powell is a lecturer in health psychology at the University of Manchester. She is interested in how students’ learning may be improved through practicing reflection. Her other research interests include psychological aspects of undergoing medical procedures, use of self-testing technologies and physical activity.

Panos Vlachopoulos is Associate Professor and Associate Dean Quality and Standards in the Faculty of Arts at Macquarie University in Australia. Panos has international experience as an academic educator and researcher in the areas of online learning, learning design and reflective practice.

Rachel Shaw is a Reader in Psychology and Health Psychologist at Aston University. Her research focuses on care and communication between healthcare professionals, patients and their families, collaborative decision-making, developing behaviour change interventions for healthcare professionals, and experiential learning.

Many thanks to the MSc student participants for not only engaging so well with this new assignment but also generously volunteering their logs for analysis and themselves for focus group discussions. This research was conducted at Aston University, Birmingham, UK. At the time of conducting the research, RP was supported by a Research Councils UK fellowship at Aston University.