Grace Farhat, Jennifer Bingham, Julie Caulfield and Sandra Grieve, Queen Margaret University, UK

The shift from school to university has been deemed to be a challenge for most university students (McMillan, 2013). Students find it difficult to adjust to a new environment (Murtagh, 2012), and there is often a disparity between student expectations and experience (Crabtree & Roberts, 2007). McMillan (2013) noted that new students find it problematic to cope with the challenging social and academic demands of university life. In addition, students receive little information before going to university. This can result in them making wrong decisions about which course or institution to choose (Thomas, 2011).

Previous research showed that schools do not adequately prepare pupils for higher education (HE) in terms of approaches to learning, teaching and assessment. Neither do they offer an appropriate introduction to independent learning, which is an important university study skill (Crabtree & Roberts, 2007). Students also struggle with academic writing as they are unsure about how to write assignments and how they are assessed (Murtagh, 2010). They are uninformed about taking notes and have little experience of collaborative learning. Moreover, they do not acquire sufficient time management and IT skills at schools, and rarely communicate and interact in front of a large audience (Lowe & Cook, 2003). This lack of preparation to HE leads to an increase in drop-outs among students. However, drop-outs are not the only issue. The lack of preparation to HE could affect students’ interest and decrease performance even among those who complete their studies (McMillan, 2013). Therefore, students who ‘struggle quietly’ also represent an important challenge for universities (Lowe & Cook, 2003).

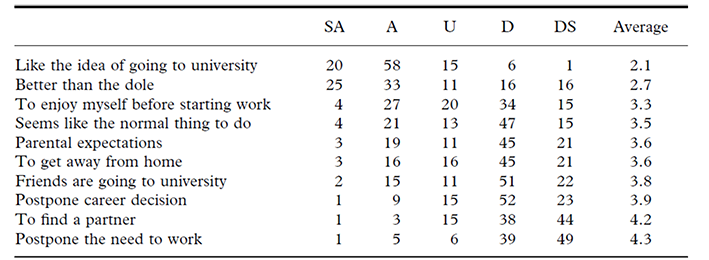

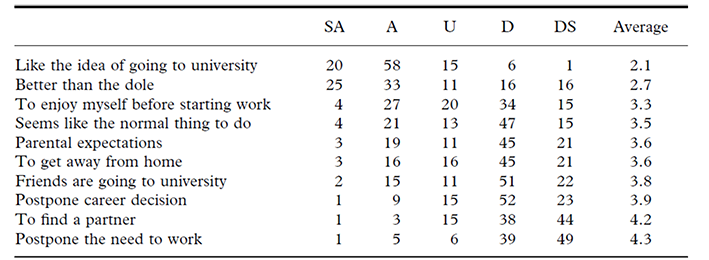

In a survey undertaken on 691 incoming students at the University of Ulster, results showed that 18% of students had no idea about university ways of assessment, and 17% had no information at all about what available options to select in their first year. Furthermore, 39% of the sample did not have the right expectations about the teaching style used in universities. This was also previously mentioned in the literature (Tranter, 2003). A considerable percentage (22%) of students did not expect the high workload and were struggling with it. Students (31%) also found adapting to an independent study approach more difficult than expected, and 19% were unsure whether it was the right decision to go to university two months after starting their course. Overall, it appears that 20% of the students fail to make a successful transition to university (Lowe & Cook, 2003). Some students (15%) were unsure about their course choice. Importantly, student motivations for coming to university seemed to be for reasons other than for the career path they aim for (Table 1). For instance, students are mostly motivated by the idea of going to university or to enjoy themselves before starting their careers, or because of the usual expectations to go to university by society, friends and family.

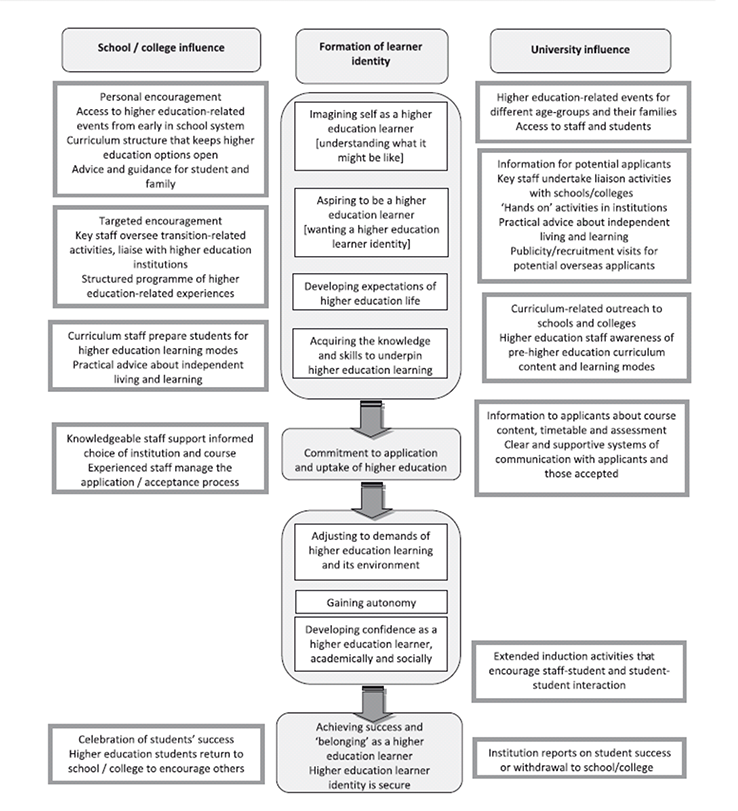

This would suggest a need to enhance student transition in order to improve achievement, and thereby avoid under-performance and possible failure. Preparing school pupils for university can help them have better achievements in the future (Lowe & Cook, 2003). Many approaches have been considered. Lowe and Cook (2003) suggested that the key solution is at both the pre-entry and the post-entry stages. Bridging the gap between students’ prior expectations and experiences would be helpful to let the students know what to expect when entering university. Moreover, as it has been shown that some students struggle emotionally to adapt to a new environment (McMillan, 2013), introducing students to this environment prior to the start of studies might help them to struggle less. Briggs, Clark and Hall (2012) proposed a system of transition where schools and universities are involved to help the student develop a learner identity. From a school point of view, it is important to involve knowledgeable staff who support pupils through applications to university and to encourage them to go into HE by means of organising events and providing advice. The university could contribute to improving learner identity through conveying clear information to school and applicants regarding course content, timetable and learning modes and assessment (Figure 1). In the final report of the Commission on Widening Access in Scotland, the potential effectiveness of bridging programmes was mentioned as a way to improve attainment, increase aspirations and smooth the transition into HE. However, the current programmes are relatively limited and the places offered are also restricted (Scottish Government, 2016)

(Lowe and Cook, 2003)

Survey included incoming students

at the University of Ulster. The average score represents the importance of

each reason as stated by the students

SA (Strongly agree), A (agree), U

(undecided), D (disagree), DS (disagree strongly).

Table 1: Reasons for coming to university as stated by incoming students

It is worth mentioning that the issue of transition from school to HE appears to be a problem for most university students at national and international levels. For instance, Strecker (2014) conducted several focus groups on school pupils in Catalonia and identified that the latter face pressure before going to university, and experience fear of being unsuccessful on academic and social levels. Moreover, Bridges (2015) identified the need for schools and universities to work in a close partnership in order to facilitate transition among pupils in Kazakhstan. Therefore, developing initiatives to enhance this aspect of transition would benefit university students worldwide.

Figure 1: Transition system suggested to support building a learner identity among incoming university students (Briggs et al, 2012).

Smooth transition from school to work has been deemed to have an important impact on careers in the longer term. It has been stated that unemployment of young people could affect their career as adults (Dorsett & Lucchino, 2014a).

Limited studies have considered issues arising in the transition from school to workplace. It appears that the experience of transition to work is mostly successful for young people (at age 16). In a study involving 1352 participants, only 10% of the sample seemed to struggle with transition to work. The reason of this difficulty has been mostly attributed to the poor decision taken at the time of leaving school (Dorsett & Lucchino, 2014b). According to Furlong and Cartmel (2004), one of the ways to avoid this is to present post-16 year olds with clear information on the employment options available for school leavers, in order to allow them to move steadily from one outcome to the next (Furlong & Cartmel, 2004). It is then important to provide effective career advice and assist students in job hunting in order to help them accomplish this goal (Dorsett & Lucchino, 2014a).

Widening access or participation into HE consists of developing approaches that give an equal opportunity for people to learn regardless of their background and personal situations. This has been regarded as an important policy in Scotland (Gallacher, 2006). It has been described that Scotland has a moral, social and economic duty to ensure equality in HE (Scottish Government, 2016).

The final report of the Commission on Widening Access stated that giving a fair opportunity to all people to develop their skills and talent is key to improving their economic potential. Therefore, equality to higher education is important (Scottish Government, 2016). The Scottish Funding Council aims to increase the number of students in Higher Education from economically and socially disadvantaged groups. Many programmes have been previously considered for this purpose, such as the SWAP (Scottish Wider Access Programme) the aim of which was to support partnership between colleges and Higher Education and to create possible routes for adult learners to go into HE. In addition, some qualifications were developed to provide opportunities and allow the system to be more flexible such as the Higher National Certificate (HNC) and the Higher National Diploma (HND) (Gallacher, 2006). The latter qualifications can be used to enter university or go straight into the workplace.

However, it has been clearly stated that widening access does not mean that university should be a priority for all pupils, yet they should be given the opportunity to do so. Pupils who do not want to go to university should be presented with opportunities that correspond with their aptitude and ambition (Scottish Government, 2016).

The South East Scotland Academies Partnership is a collaboration between Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh College, East Lothian Council, Midlothian Council, Scottish Borders Council, City of Edinburgh Council, Borders College and industry partners. This partnership between schools, colleges, university, local authorities and industries is supported by the Scottish Government and the Scottish Funding Council. The Academy model aims to offer opportunities for 15–18-year-old pupils from secondary schools in South East Scotland to develop their skills and career options.

The model started with 35 young people in 2012 joining the Hospitality and Tourism Academy, a collaborative initiative between Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh College, East Lothian Council and a range of major hotel chains. The key impacts were to raise aspirations, enhance skills development and shorten the learner journey by providing education up to SCQF (Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework) level 7; equivalent to university level. For the latter, SCQF represents a way of comparing Scottish qualifications and makes it easier to transfer between different learning programmes (Scottish Qualifications Authority [SQA], 2016).

Four Academies have now been set up in South East Scotland: Health & Social Care, Hospitality & Tourism, Food Science & Nutrition and Creative Industries (South East Scotland Academies Partnership [SESAP] 2015). These areas have been recognised by the Scottish government as key areas of economic growth that provide considerable opportunities for employment and present a need for more graduates to support the development of these sectors.

Currently, over 300 pupils are involved with the Academies. The full Academy programme is part-time and delivered over a one or two-year period, in the final one or two years of secondary school (S5 and/or S6). Academy students attend college 1-2 times a week and Queen Margaret University on a number of Fridays during the year. The Academies deliver a range of industry related qualifications across school and university level. Students can choose to complete just one year before using the transferable skills they have acquired in their first year to move to University, College or work. After successful completion of the full two-year Academies programme, students will be presented with a range of opportunities to progress into Further or Higher Education or go directly into employment. In most of the Academies, students who successfully complete two years of the Academies can gain a recognised qualification (such as an HNC). The HNC will give them the possibility of getting a direct entry into year 2 of a relevant university degree and shortening the learning journey from 4 years to 3 years (for a BSc/BA Honours degree) and from 3 years to 2 years (for a BSc/BA ordinary degree). The HNC qualification also opens many opportunities for young people to work in the industry of their choice. For instance a student gaining the HNC relating to the Creative Industries can take on posts such as Editing/Production assistant in Filmmaking or a Runner (supporting productions and editing departments).

Subjects studied vary according to the Academy of choice. For example, Food Science and Nutrition Academy students study a range of units such as Chemistry, Microbiology and Quality Health and Safety in industries, while Health and Social Care Academy students study topics such as Principles of Care, Health Safety and Protection Issues in Care settings, and Working in Health and Social Care settings.

The main focus of the Academies is to help young people smooth the transition between school, college, university and employment; to maximise their educational opportunities and develop transferable skills; and to support the development of Scotland’s most important industries.

The Academies focus on the university pre-entry stage. They are presented as a system of planned extended transition from school to university, which allows students to be introduced to the university and to make better decisions regarding course choice. Pupils participate in an induction day at the university at the beginning of the Academic year, including campus tours offered by supportive university student guides. Throughout the year, Academies students have the opportunity to get in touch with current undergraduate students, who share their experiences. This gives them a clearer sense of what it is like to be a university student. Academies students also communicate with current lecturers and other staff. Lecturers are involved in teaching the students. Staff are also available for advice on career/university choices. According to Briggs et al., (2012), this can help establish connections between pre-university and university experience. Pupils learn how to act as university students (Fazey & Fazey, 2001), and are offered a real taste of what university life is like. This is particularly important not only to enhance transition, but to find out whether university is the right choice for some pupils. In fact, introducing pupils to university might be helpful to raise aspirations; if they realized the university is not for them, then college, a modern apprenticeship or work might be alternative options. Students who make those decisions are supported by the coordinators and members of staff at the college and university.

Academies also offer the advantage of giving students a flavour of a specific career in a certain field. Students choose one of the four Academies according to their interests. The choice of one of these fields might be helpful in knowing what to expect when choosing a university degree in the same area of study. In addition, this might give them a better insight into their choice of university course. For instance, a student interested in science realised after joining the Food Science and Nutrition Academy that science was not the right career choice for him. The Academies may then be helpful in lowering course dropouts at the university. This can reduce the burden on universities as well as the financial inconvenience and the waste of the students’ time.

In collaboration with the colleges, Academies students acquire considerable experiences about independent learning. At the university and the college, they are guided on how to develop learning goals, seek resources and apply appropriate learning strategies; the latter all being considered components of independent learning (Chan, 2001). In addition, pupils start to develop a set of academic skills that may be lacking in the school curriculum, such as time management skills, personal development planning and research and referencing skills. Importantly, they are introduced to report and essay writing, which is a major shift from the way of assessment in schools (Cook & Leckey, 1999). Therefore, they have an introduction to the type of academic writing required in most university degree courses.

Furthermore, the Academies help to improve student presentation skills, which are essential for university and future jobs. The project aims to improve confidence and the ability to present in front of a large group. Students are constantly encouraged to ask questions and to discuss ideas in class. Also, in some local authorities’ areas, Academies students are required to travel to the college and university, thus they are becoming more autonomous practicing valuable life skills in preparation for being more independent after school.

In addition to the academic learning, the Academies focus on the pedagogic aspects of transition by offering students the possibility to become familiar with the university environment. Also, it offers young students the opportunity to socialise with other students from different schools, and thereby increase their confidence. All these factors can make students more emotionally prepared for transition. Overall, joining the Academy aims to make students clearer about expectations, which might be helpful to predict student experience, the latter being considered essential in the preparation for HE (Murtagh, 2012).

The Academies project has been playing a role in widening access by allowing the programme to be offered to most schools in Edinburgh, the Lothians and the Scottish Borders. The possibility of joining the Academy has been offered to 55 schools and includes lower socio economic areas and rural areas hard to reach such as the Borders schools. Transport funded by the Councils provided the opportunity to do this.

Although it mostly appears that the transition to Higher Education seems more problematic than transition to work, attention should also be paid to this transition. In fact, young people are often unaware of the range of jobs and opportunities available to them in the industry (SESAP, 2015). The Academies focus on offering transferable employability skills that help the transition to work. As universities are not the right choice for everyone, the Academies provide knowledge and qualifications to help students find work in their industry of choice.

In the Academies, industry partners offer work placement opportunities, providing young people with vital hands-on practical experience (SESAP, 2015). For instance, Creative Industries Academy students are offered placements in festivals and theatres, whereas Hospitality and Tourism Academy students take up placements in a variety of institutions such as hotels and restaurants. By working with industry specialists, they are introduced to a host of opportunities and often guided to positive destinations.

A survey was emailed to all Academies students. The aim was to get an idea of whether the Academies fulfilled their goals with regard to different aspects of student transition. The survey was conducted via Bristol Online Surveys (BOS) and students were asked to answer multiple questions regarding their experience in the Academies, and what they mostly enjoyed but also disliked. Questions varied between multiple choices, open-ended and scaled. There was also a query about overall satisfaction of the Academies. The questionnaire was distributed at the end of the Academic year 2014-2015 and was open to both year 1 and year 2 students of the Academies. Students were given a timescale of one month to respond.

Seventy-three Academies students completed the survey. Results showed that 68.5% of students who responded stated that the Academies made them more likely to go on to college or university. Also, 73.61% of the sample agreed that the Academies helped them to acquire independent learning skills. Moreover, 82.2% of students mentioned that the Academies increased their confidence. Students mentioned that this experience helped them acquire presentation skills and improved life experience by making them more independent. The majority of respondents (80.8%) stated that the Academies experience improved their communication skills and their knowledge of the chosen industry (86.3%). Also, some comments by respondents were as follows:

I have found that I don't enjoy some of the science areas as much as others and so it helped me to decide what I want to do at university.

The Academies helped me to experience new things but also helped me decide what areas I would like to work in in the future.

I became able to communicate more with new people.

However, some adverse comments stated by the students deserve more attention in order to improve the experience and help meet the Academies objectives. For instance, some students stated that visiting the university a few times a year was not enough to build a university experience, and the Academies lack further information about university course choice. In addition, some Academies students mentioned that they needed clearer information about the Academies course content as it did not meet their expectations. A communication problem between the Academies and the schools has also been mentioned. Lastly, the transport problem from and to the college and university has also shown to be a considerable issue especially for students living in rural areas.

The survey gave valuable insight into the students’ experience. A larger survey addressing different aspects of student transition is planned to be distributed to current Academies students. Also, as only 25% of Academies students have completed the survey, efforts towards increasing the response rate is presently being considered for future work. This relatively low response rate is mostly explained by the fact that the survey was distributed at the end of the Academic year when students are involved in different activities, or have left school.

Furthermore, it would be important to acquire information about student destinations after leaving the Academies in order to reinforce the role of the Academies in smoothing transition to HE and employment.

One of the survey’s limitations is its main focus on transition to university, while transition to employment has been an important objective of the Academies. Therefore, this aspect needs to be taken into consideration in future surveys/evaluations.

The Academies programme is seen as playing a considerable role in smoothing transition and widening participation. It helps students build their confidence, acquire university study skills and enhance their communication skills. Similar projects are then needed to help students have better achievements. As it seems that struggling in the transition to HE and employment is a problem for most university students, these sorts of programmes can be beneficial at a national and international level.

The authors/coordinators for the different Academies have been involved in curriculum planning, teaching sessions, linking between university members of staff and students and providing support for students. The Academies have been able to fulfil most of their objectives and many lessons have been learnt to date along the four-year project. As coordinators, we have developed a much better understanding of issues related to student transition. After experiencing four different cohorts of students, we now recognise the importance of pastoral support in helping students throughout transition. Individual student support was sometimes needed. Also, we have noticed that this experience has been mostly valuable for students with regards to gaining communication and independent learning skills.

It is also worth mentioning that joining the Academies gave students the potential advantage to shorten their learning journey from four years to three years for an undergraduate degree, assuming that they gain an HNC at the end of the two-year programme. This has been perceived by us as one of the potential objectives of the Academies. However, we have remarked that most students who were offered this opportunity preferred to go into year 1. This was mainly to avoid struggling academically and socially. Further investigation is needed, but it seems that shortening the learning journey may not be an important objective for school pupils despite its time-saving and economic benefits.

Despite the importance of the topic, research is still limited regarding student transition. Many studies have discussed the issues arising in student transition (Murtagh, 2012; Thomas, 2011; Lowe & Cook, 2003). Therefore, studies describing strategies for improving student transition are needed. In addition, there is a need for experienced school staff who have information on student transition, and who can enhance their teaching strategies to help students be better prepared for Further/Higher education. Additional support from school staff could also be helpful in building expectations for university and providing clear information for work. Moreover, University staff need to be more involved in student transition, and be more supportive of the incoming students who are facing a major challenge in their lives. Better communication between university staff and students would definitely be valuable. Lastly, following the aspirations of Academies students in a longitudinal manner would be important to find out whether the Academies match their objectives.

The Academies create an opportunity for pupils to be better prepared for higher education: introducing students to a new environment, establishing connections with enthusiastic and friendly university staff and doing pre-university class activities can all help to ease student transition. Giving students the opportunity to act as university students makes them increase their sense of belonging to the new environment. Students have acknowledged the positive influence of the Academies on their social, communication and independent learning skills. The Academies are seen as a potential way to widen access to HE and help students make more informed choices, increase their achievement and lower dropout rates in universities. The Academies are also presented as an effective way to ease transition to work and improve lifetime careers.

Grace Farhat is the Food Science and Nutrition Academy Coordinator at Queen Margaret University. She has a PhD in Public Health Nutrition and has previously worked as a university lecturer in nutrition for many years. She is an Associate Fellow for the UK Higher Education Academy.

Jennifer Bingham works at Queen Margaret University and is the Hospitality and Tourism Academy Coordinator. Jennifer has experience working in the hospitality and events sectors including operating her own business and has worked for over 15 years in further and then higher education.

Julie Caulfield is a Lecturer in Occupational Therapy, and Practice Education Tutor at Queen Margaret University (School of Health Sciences) as well as Academy Coordinator for the Health and Social Care Academy with SESAP (South East Scotland Academy Partnership). She is a HCPC registered Occupational Therapist.

Sandra Grieve joined Queen Margaret University in September 2004 predominantly teaching media relations at undergraduate level. Since 2012 she has worked in partnership with schools and colleges in South East Scotland to ensure consistent and coherent delivery of the Creative Industry Academy programmes across a variety of campuses.