Anna J. Robb and Brenda Dunn, University of Dundee

The advances made in technology over the last twenty years have had a great impact on the lives of learners today (Rheingold, 2012). Education establishments across the globe, from schools to universities, are responding to these developments by reviewing the way they currently deliver education and learning, with debates developing concerning the effectiveness of both traditional and online approaches (Barber, Donnelly, & Rizvi, 2013). The success of e-learning, however, ultimately depends on the people involved, both staff and students, and their skills and attitudes. This paper explores this issue in relation to student participation of online discussion boards.

There are a range of definitions of ‘e-learning’ which demonstrates the evolving understanding of this form of learning in the 21st Century (Sangra, Vlachopolous, & Cabrera, 2012). For the purposes of this paper, the definition provided by JISC will be adopted as they provide advice and support to HE institutions across the UK: ‘E-learning’ is “learning facilitated and supported through the use of information and communications technology” (JISC, 2012). In today’s world, HE institutions increasingly provide a range of face-to-face and distance learning modules with e-learning playing a key role in delivery (Annetta, Folta, & Klesath, 2010). This is primarily done through virtual learning environments (VLE) which consist of a range of on-line tools that allow for the delivery, assessment and tracking of learning within an institution (JISC, 2016). It is the role of the lecturer to guide and facilitate active learning through the innovative use of technologies and new media. The relationship the lecturer has with the students, as with traditional teaching, is therefore essential in developing a VLE which will meet the students’ needs (Mallinen, 2001).

Assumptions have been made that because students live in a media-enriched world they automatically know how to use VLEs effectively as engaged learners, however research to the contrary is beginning to dispel this notion (Winter, Cotton, Gavin, & Yorke, 2010). Learning through the VLE requires different skills to those in other learning environments and learners require time for training and support (Mapuva, 2009). A major barrier to this, however, lies within the learner themselves. The LLiDA project (Beetham, McGill, & Littlejohn, 2009) identified a range of challenges in the provision of digital learning literacy, the first one being that “Learners’ information literacies are relatively weak but learners have little awareness of the problem” (p. 4).

One of the challenges presented to a tutor working through a VLE is to support the students in becoming active online learners (Conrad & Donaldson, 2004). Various models of online learning exist though the roots lie in Salmon’s 5-stage ‘Model of Teaching and Learning Online’ (Salmon, 2004; Conrad & Donaldson, 2004; Moule, 2007; Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Vlachopolous & Cowan, 2010). The model consists of five stages of development that a student will progress through to become fully responsible for their own learning using online tools collaboratively (Salmon, 2004, P. 28): Stage 1 – access and motivation; Stage 2 – online socialisation; Stage 3 – information exchange; Stage 4 – knowledge construction; Stage 5 – development. Salmon’s model is upheld as a popular model of good practice however this has been challenged in recent years (Moule, 2007; Vlachopolous & Cowan, 2010). The model promotes a ‘one size fits all’ approach and that this may not actually be appropriate in other settings (Lisewski & Joyce, 2003; Moule, 2007). The model also ignores a range of learning theories choosing to focus primarily on the strengths of the social constructivist pedagogical approach. These criticisms however could be levelled at any developmental model of learning. However, this is still the most popular and commonly cited model of facilitating online learning and therefore it is used as a reference for good practice.

The focus of this paper is on the participation in a module, online, discussion board, supporting students from Level 1 and 2 towards the co-operation and collaboration expected at Level 3 and Level 4 of Salmon’s model (Salmon, 2004). Electronic communication tools such as online discussion boards are an essential part of online learning, in enabling students to move from being passive to active online learners (JISC, 2004b). They are also a key tool in Salmon’s approach to delivering activities which are named as e-tivities (Salmon, 2002). However, the value of the learning that takes place on discussion boards has been questioned (Robinson, 2011; Krentler & Willis-Flurry, 2005; Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Dennen, 2005). Research has revealed that students tend to enjoy using the discussion boards however participation levels can vary and this can affect performance in assessment activities (Robinson, 2011; Krentler & Willis-Flurry, 2005; Dennen, 2005; Beckett, Amaro-Jimenez, & Beckett, 2010). Additionally, types of activities which work best are those which encourage collaboration through the discussion boards; Borokhovski, Tamim, Bernard, Abrami and Sokolovskaya (2012) states that discussion boards which provide a means of communication for students but do not encourage co-operation or collaboration do not produce high achievement results. The researchers perceived this to be an issue with the module discussion board that is the focus of this paper.

The role of the e-moderator is also an essential component of a successful discussion board. Salmon (2004) believes that the e-moderator is someone who “presides over an electronic meeting or conference…” (p. 4) with the aim of encouraging interaction and communication through modelling and knowledge-constructing activities; they do not require more qualifications than the participants but should at least be working at the same level and should also have a confident understanding of the tool and the capabilities of the participants. Research has determined however that the role of the e-moderator is predominantly taken by the tutor of the module (Dennen, 2005).

Finally, an essential factor in the success of online discussion activities is that students need to understand the benefits of using these tools in terms of their own learning and development (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Dennen, 2005; Beckett, Amaro-Jiminez, & Beckett, 2010). Often, students look to the tutors as e-moderators to guide their learning, as they are seen as the ‘experts’ however this can have a negative impact on the development of autonomous learning skills as students tend to direct posts to the tutor rather than to their peers (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Dennen, 2005). The alternative of designing a space which is fully student-centred also has its drawbacks as the quality of the discussion between students can be limited to question and answer sessions rather than building discussion and critically analysing issues (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Vlachopolous & Cowan, 2010). Lack of participation by fellow students can also be a de-motivator (Beckett, Amaro-Jiminez, & Beckett, 2010). The ideal therefore is for “…students and instructors to take responsibility to construct and share knowledge and ideas” (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012, p. 27). In order for this to happen both the student and the instructor need to have a shared understanding of how learning occurs and the role of autonomous learning in these online environments. The individual needs of students also should be taken into account before the student commences an online course or module, rather than assuming that all students approach online distance learning in the same manner with the same skills, although this does present challenges in terms of resources such as money, staff and time (Lisewski & Joyce, 2003; Moule, 2007).

This paper is based on work conducted as part of a case study for the Elene2learn project led by the Elene2learn consortium (Elene2learn, 2013a; Elene2learn, 2013b). The consortium consists of an international network of educational stakeholders from across secondary and higher education establishments, facilitating a range of case studies across Europe concerning digital literacy approaches and the development of learning to learn competencies.

The focus of this particular case study was a distance learning, childhood practice degree programme in Scotland. Students work part-time on this degree, as well as being practitioners in a variety of educational and childhood settings. The students range in age from twenty-four to sixty-four and can enter the programme at different stages dependent upon the level of previously attained academic credit. This means that students undertake the degree with varying levels of prior experience both in terms of secondary and further education and professional practice.

Participation in the Elene2learn project allowed the researchers to focus on two aspects of online distance learning: firstly, the issue of managing the continuous transition between work and the world of online higher education for students (Elene2learn, 2013b); and secondly an examination of the issues surrounding the active participation of these students in virtual learning environments. The focus of this paper concerns the latter.

The degree programme is administered through the university virtual learning environment (VLE); in this case Blackboard. The necessity to be working in addition to studying means that the majority of students work in isolation and are rarely able to meet face-to-face; synchronous online activities are also difficult to arrange because the majority of students work long, irregular shifts. For each module, a core tool that all students are expected to make use of is the module blog; this tool is primarily used as a discussion board tool where students and tutors are encouraged to write and respond to posts linked to the learning in the module. In addition to this, all students, regardless of the module they are currently working on, can make use of a student community blog space. The aim of the blogs is to provide peer support and build a sense of community, however in practice few students on the degree programme actively or voluntarily participate in this online, asynchronous, learning space. Although this is a commonly experienced problem, the students are distinct from other undergraduate students in terms of age, prior professional experience, prior learning and particularly confidence and motivation. In order to manage a childhood setting in Scotland it is now necessary to achieve a SCQF Level 9 qualification which meets the requirements of the Scottish Social Services Council; many of the students have worked for a substantial number of years in childhood settings but are now required to obtain a qualification in order to remain in the job that they currently have, whereas others are starting out in their chosen career and are completing a qualification as a matter of course. This means that levels and types of motivation also vary greatly for each student. The range of experiences and backgrounds of the students however should also be seen as a strength, particularly in terms of opportunities of peer-learning. A small scale action research project was therefore designed and implemented which would draw upon this strength in the online discussion boards by creating the role of the student as co-moderator. The types of discussion and learning which developed within the collaborative community were examined as well as the impact on student confidence as learners.

In accordance with Salmon’s five-stage model, the majority of students who participated on the blog were currently working at Level 2 (online socialisation) and some were only working within Level 1 (access and motivation) despite having been on the programme for a number of years and using the VLE continuously during this period (Salmon, 2004). Ideally, for those in their final year of study students should be working co-operatively (Level 3) and collaboratively (Level 4) and so the aim of the project was to put a change in place that would begin to make improvements. An action research methodology was therefore adopted by the researchers. Key features of this methodology is that it is collaborative, emancipatory and participatory (Mac Naughton & Hughes, 2009, Sarantakos, 2005).

For the purposes of this project, a group of co-moderators was put in place consisting of student volunteers. Their role was to oversee the blog, instigating and managing discussions with their peers. The tutor continued the role of moderator however this primarily consisted of supporting the co-moderators rather than taking an active role on the blog itself. It was felt that by putting this change in place the emphasis would be on developing a collaborative learning relationship between the students through the blog, rather than the formal relationship between tutor and student (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Dennen, 2005). The project was conducted during a four-week period and focused on 25 students completing the penultimate module for the programme; ethical approval was sought and granted following University procedures. It was felt that these students were most experienced in using the tool and that it was appropriate that they should be working collaboratively and analytically. Four student volunteer co-moderators were found, with each student acting as co-moderator for one week at a time. In preparation for becoming a co-moderator, the student volunteers participated in two synchronous online webinars with the module tutor; the role of co-moderator was discussed and the webinars provided the opportunity for the students to build relationships through the sharing of online collaborative experiences to date. Following these sessions each co-moderator was issued with a guide sheet providing details of the role and expectations, reinforcing the webinar discussions. During the relevant week of responsibility co-moderators were free to submit posts of their choosing related to the content of the module with additional tutor support provided if requested.

A mixed methods approach was adopted (Sarantakos, 2005). Two questionnaires were sent by post to all participating students; one at the start of the project and one at the end of the four-week period (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011). Twenty-five students received the questionnaire with nine returning the first one and two returning the second. The Likert Scale questionnaire focused on how students used the module blog and also on their perceived levels of confidence and competence with using the blog tool; students were also given the opportunity to make additional comments. The data gathered from these questionnaires was supported by data gathered from a focus group that was conducted in the last week of the project. This focus group was conducted face-to-face with five module students, one of which was a co-moderator. Finally copies of all the blog posts created during the four-week period were collated. Method triangulation was employed to ensure validity and reliability of results from data gathered from a limited number of participants (Sarantakos, 2005)

There were two stages of thematic analysis of the data (Tracy, 2013). As the project was being conducted under the auspices of the Elene2learn project, primary analysis of the data was completed using the researcher’s choice of pre-determined competences in relation to transition: communication (reading and writing); collaboration with peers; thinking, problem-solving and decision making; being creative; motivation and confidence. These competences were used to create the first set of codes (Bell, 2010). In terms of the questionnaire, the themes were considered during its creation and pilot with multiple codes applied to questions in some instances; the results were collated in the form of graphs and the mode calculated for each question (Sarantakos, 2005). The researchers then analysed and independently coded the focus group transcript and the blog posts; further discussion led to modification of coding and also the emergence of a new set of codes, independent of the Elene2learn competencies which allowed the researchers to explore and identify any possible issues in relation to the active participation of students in an online environment (Gray, 2014). The analysis was done manually.

Twenty-five questionnaires were sent out at the start and the end of the four-week period. A third of the questionnaires were returned in the first group (nine in total) and two were returned in the second group. In the focus group it emerged that the timing of the project had caused issues for the students, because it coincided with a critical highpoint in the calendar of events in educational settings (the writing and issuing of school reports). Therefore students felt they were not able to participate as fully as they would have liked on the boards. From the nine questionnaires that were returned in the first group, only five students had accessed the blog prior to the project; one of the students who had stated that they had not accessed the blog commented that “I am not all that good with the computer – I do not blog on a personal level. I do think it is good way to keep in contact with other students. But would find it time consuming”.

Of the five students who had accessed the blog, three stated that they were regular users, accessing the blog at least twice a week, however all five respondents stated that they did not make regular contributions. The positive value of the blog was highlighted in comments indicating that was a place to connect to their peers, removing feelings of isolation. These students felt that the blog was a place to get to know their peers and their tutors and that it encouraged collaboration amongst their peers, however the majority of students used the blog as a place to ask questions but not to answer them. In terms of the negative aspects, comparisons were made with face-to-face methods, which were seen in a more positive light. One student stated that “I have accessed the blog but prefer using other tools, such as discussion at workshops and with my colleagues/module tutor face-to-face or via telephone”.

The aim of the second questionnaire was to determine if there had been a change in student attitudes and opinions towards the blog tool as a result of the change that was put in place. Unfortunately, it was impossible to draw any conclusions with regards to this due to the low response rate. However, the two respondents, despite indicating opposite levels of confidence using the blog, did both state that the value of the blog lay in its ability to provide support to students through sharing common experiences or answering specific questions.

Activity during the four-week period increased significantly compared to the weeks prior to the change being put in place though the majority of activity took place between the four co-moderators; in total, one hundred and three posts were submitted, consisting of twenty-three separate discussions. Of the twenty-five students who were currently taking the module, only eight made contributions.

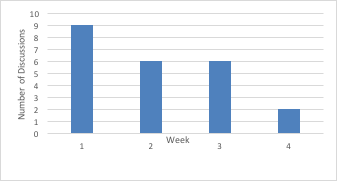

Figure 1: Blog Activity: Number of Discussions

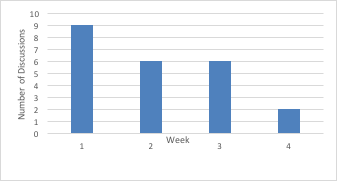

Figure 2: Blog Activity: Number of View

Figures 1 and Figure 2 indicate that there was a decline in participation during the four weeks. Viewings in Week 1 were highest with one discussion entitled ‘Are we making a difference?’ recording thirty viewings and two responses from co-moderators. By Week 4 only two discussion threads were posted: the first one garnered twelve views and two responses, each from other co-moderators; the final post was viewed fourteen times and received one comment from a co-moderator.

During the first phase of analysis of the content of the posts three predominant themes were identified: communication; confidence; collaboration. In terms of communication the language used by students when writing their posts was formal and academic which is in contrast to the posts that were written on the same blog prior to the project commencement. The students were polite and took time to thank each other for making contributions. Co-moderators posted up articles that they had found useful or relevant, and they made a point of ensuring that the reference was written in the correct format; referencing is a predominant issue for students when submitting written assignments.

Collaboration with peers was not evident. Through the posting of articles and discussions, co-moderators sought the support of their peers to develop these lines of thought further, however, this did not happen. The majority of posts submitted by students other than the co-moderators consisted of seeking clarification on a particular issue related to the assignment; posts which often needed to be answered by the e-moderator (tutor).

Co-moderators were conscious of the lack of confidence that existed amongst their peers and as a result many of the posts featured supportive comments, telling students that they were making a difference, and providing support to other students who had posted up concerns related to completing the module. One co-moderator, aware of this issue, used the board as a way of communicating to the other students the days and times when the co-moderator planned to use the University library, so that students could meet face-to-face as a group.

During the second phase of analysis an additional theme was identified: the value of the blog through the eyes of the students using it. The content of the posts demonstrated that the students primarily used the blog as a place for seeking advice concerning the technical aspects of writing the assignment and as a place to seek support whilst completing the module; the depth of learning that occurred when compared to the module learning outcomes was therefore quite minimal.

Finally, it emerged from the posts that volunteering to be a co-moderator was seen to be a significant challenge for the students. Upon commencement of their week, co-moderators often sought support, which they all received from the other co-moderators. They were also supportive of each other when someone’s week had finished; the phrase good luck was used by all co-moderators particularly during the transition from one to another.

The focus group provided data which helped to corroborate the results of the questionnaires. Students appreciated the fact that for the four weeks of the project, regular contributions were being made to the module blog. This had encouraged students to actively view the blog on a more regular basis which is consistent with the increased number of viewings during this period. As one student said “…I do think that over the four-week period the blog was a lot more interesting because people, the moderators obviously had to think about things that you could post to engage people, so I think it was a lot more interesting than what’s normally on the blog”. The role of the blog as a support mechanism was also greatly appreciated and it was seen as a place to share worries, challenges and success; another student felt “…the distance learning I felt very much in isolation and would leave it to the last minute at least if you are going on the blog you’ve got that dialogue and communication with students”.

The role of the co-moderator was discussed and it was evident that the students had appreciated the level of commitment that the co-moderators had shown during the timescale of the project. The co-moderators also played a role in increasing the levels of confidence of other students to participate, though this was not evident in the actual number of students who did make contributions. As one student said “I think for me it definitely did [impact on my confidence] because it made me confident enough to go on and put a comment to say how unconfident I was feeling about blogging”. Reinforcing this, a co-moderator who was present at the focus group, felt that she would not have been so active on the blog if she had not volunteered to take on the role and that this had boosted her confidence.

The supportive aspect of the blog was a key feature commented upon; it was felt to be reassuring that there was a group of them together working on the same module. A one student said “don’t worry, we’re all in the same boat”. Another popular feature was the fact that students were encouraged to attach their photo to their profile; it was felt that this was a positive step towards personal connections between students.

The focus group discussion highlighted two possible barriers to active participation in an online environment; these were linked to confidence and time. Lack of confidence was discussed and mainly attributed to a concern about making mistakes when writing posts, rather than a lack of confidence in using the online tool itself. Students therefore preferred to read what others had written rather than write their own response. As one student highlighted though this creates “…a vicious circle…I think we’re all the same that we might go on and think ‘Oh that was really good to read about that on there’ but we don’t comment on it or answer if somebody’s put it up”.

The other issue concerned a perceived lack of time amongst the students. The students on this degree programme have to manage a full-time equivalent job and a family; time for studying is limited and often the reason why students opt for distance learning is due to the flexibility it offers. The students felt that their study time should primarily be dedicated to completing the assignment and that contributing to the blog was an additional extra. As one student states “You’re focusing so much on what you’re doing and what you’ve got to piece together and then to go on the blog and have to contribute, or post something, to show that you’re working along with something is another task in itself.”

This project explored the issue of active participation in online environments. It became apparent as the project progressed that the change that had been put in place, students as co-moderators, had generated increased interest amongst the students in terms of accessing the blog; the number of viewings of posts increased significantly in comparison to activity prior to the change being put in place and during the focus group discussions, students attested to it being a more interesting place to visit. Discussion and collaboration between the co-moderators was also evident through the posts. This increase in activity could however be attributed to the fact that the students were aware that data was being gathered for a research project. However, there was no evidence to suggest that the introduction of students as co-moderators had encouraged an increase in active participation amongst the other students working on the module at that time. It was also evident that activity declined during the four-week period. This was noted by co-moderators and through their posts they tried to encourage other students to participate however this did not have a positive effect. The discussion was therefore limited in terms of depth of learning, as the discussion board was primarily still used as a place for questions and answers, concurring with recent findings in other research projects (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012).

The students themselves identified the barriers of a lack of confidence and lack of time as the principle reasons for lack of participation. The issue of a perceived lack of confidence was linked primarily to a lack of confidence in academic ability rather than in terms of using the tool. The project also highlighted the significant variances in terms of level of confidence among the students. In relation to Salmon’s model (2004) and Moule’s model (2007), the onus is on the e-moderator to facilitate learning through the various levels though it assumes that each student commences their studies with the same level of experience and confidence. Findings from the questionnaire, posts and focus group discussion would indicate that the distance learning students involved in this project brought with them varying levels of confidence. Currently users are identified by their name when they use the blog; while some users felt that adding photos to the names would be a supportive measure it is also worth considering whether there should be an option to post anonymously. Roberts and Rajah-Kanagasabai (2013) found that students were more likely to post if it was possible to remain anonymous therefore this could be a step which would encourage an increase in participation and therefore an increase in confidence.

The data gathered also demonstrate that students had minimal understanding of their role as autonomous learners in an online distance learning environment. The results of the questionnaire confirm the discrepancy between the students’ understanding of the blog as a learning tool and the actual use of the blog by students. These findings build on the work of Beckett, Amaro-Jiminez and Beckett (2010) who drew the tentative conclusion that “a paradigm shift for students in their understanding of what learning and teaching through OADs (online asynchronous discussion) may be necessary” (p. 331). However it would be beneficial to explore this discrepancy in further detail. This lack of understanding also became apparent most clearly in the focus group during the discussion concerning the lack of time available to participate on the blog. Students indicated that the blog was “taking second place to everything” and that the blog was an additional, optional activity to completing the assignment. The students discussed the blog and the assignment as two separate entities and gave no indication that the two activities are linked; the focus of the students was on the completion of the assessment as this led to passing the module whereas contributing to the blog was not seen as an integral part of the learning process. This issue is highlighted by Dennen (2005) who believes that this is an indication that the goals of the discussion board and activities are not clear to the students. Certainly, the discussion from the focus group would indicate that the blog is not valued by students and not viewed as an integral part of learning from a distance. Another point that therefore needs to be addressed is whether the online learning environment is supporting the students in their ability to learn from a distance. Segrave and Holt (2003) discuss the move from face-to-face learning to online learning environments and the negative impact that this can have if the online learning environment is not considered as a learning space but more as a place to translate face-to-face teaching to reach a wider audience. An engaged online learning environment should encourage collaboration and constructivist learning however it tends to be delivered to a group of students all at one time; little account is taken for prior individual experience, skill or understanding of learning. In this way there are similarities with face-to-face teaching in HEIs. Despite research to the contrary (Mapuva, 2009), it seems that VLEs and models of online learning are still heavily influenced by existing teaching practice in HEIs rather than HEI teaching practice adapting to meet the needs of individual students through the exploitation of the capabilities of the VLE. The discussion from the focus group would suggest that further research needs to be completed to determine whether the design of the modules and the role of the discussion boards fully support the range of needs of the students (McLoughlin, 2001; McLoughlin, 2002).

Another aspect to consider would be whether participation on the discussion board should become an assessed component of the module; Matheson, Wilkinson and Gilhooly (2012) outline a patchwork text method, with online discussion boards an essential component, assessed through a range of formative and summative assessments, which encouraged the students to develop a range of academic skills, including working collaboratively, while also encouraging them to take responsibility for their learning. Key to this however was the role of the tutor as modeller and this was not present in this action research project.

Both the focus group discussion and the content of the blog posts demonstrated that the blog was a place to have technical questions answered and a place to be sociable. For this reason, students in the focus group highlighted that it was necessary for the tutor to take on the role of moderator in order to provide correct information to students. This indicates that the students perceive a power relationship between tutor and students, with the tutor being in control and holding knowledge, rather than the two entities working and learning together (Nandi, Hamilton, & Harlan, 2012; Segrave and Holt, 2003). The students who took part as co-moderators found it to be a positive experience, admitting that they needed a push to consciously try to use the blogs. In their role as co-moderator, these students had a clearly defined purpose and reason to use the blog. Despite the efforts of the co-moderators to encourage discussions linked to reading and learning, the other students made no attempt to extend or partake in the discussions themselves. Reviewing the materials in the online learning environment to ensure that their purpose is clear and making stronger links to assessment may address this issue (Dennen, 2005; Matheson, Wilkinson, & Gilhooly, 2012).

It was always the intention of this research project that it would be a small-scale piece of action research specific to its context; the findings and discussion are limited however due to several reasons. A key limitation was the low response rate of participants. Although the students who participated gave an indication of various levels of confidence the data was gathered from students who made contributions on the blog; the voices of those who chose not to contribute are therefore missing from the data and this could have provided a broader insight into the issues of participation in an online learning environment. It would also have been beneficial to run the project over a longer period than the four weeks; this would have allowed a greater number of co-moderators and would have provided further data from which to draw conclusions regarding levels of participation and activity.

A key element of action research is the role of reflection in creating a cycle of research and action (MacNaughton & Hughes, 2009). Although the project itself did not have a long-lasting impact on the way the blogs were used, it did provide a useful insight into how the blog is perceived by the students who use it. However, the interesting aspect of this project is the possible future actions and opportunities for further research that arise because of what is missing from the data. For example, a simple next step and change would be to introduce anonymity on the discussion board to determine whether this has an impact on participation. Secondly, exploring the students’ perceptions of lack of confidence in more depth would be a beneficial next step towards ensuring the materials and structure of the online module begins to meet the needs of individuals more successfully. One approach could be to monitor levels of confidence using the online learning environment in a group of students throughout the completion of the programme rather than exploring this in the final module. It would also be worth considering preparing students for the co-moderator role in modules at the beginning of the programme and monitoring the impact of this on participation and quality of interactions. Finally, a review of the online learning environment for the module and the role of formative and summative assessment would be beneficial to ensure that it meets the needs of the distance learning student.

From a wider perspective, this paper illustrates the perceived challenges for distance learners who are new to higher education and online learning environments. The change put in place was based on an assumption regarding the levels of confidence that students would have in the final module of the programme; the results indicate that this assumption was wrong. It is therefore a recommendation of this paper that student feedback from distance learning students should focus not only on the explicit learning outcomes but also on the range of implicit academic skills that students develop as a result of participating in an online learning environment.

Anna Robb is a lecturer in education at the University of Dundee. She has worked as a primary teacher and is currently completing a PHD focused on children’s voice and art education. Email: a.j.robb@dundee.ac.uk. Twitter: @robb_anna

Brenda Dunn is a senior lecturer in education at the University of Dundee. She is currently the Programme Director of the BA in Childhood Practice. Email: b.h.dunn@dundee.ac.uk