Jennifer Leigh, University of Kent, UK

As a relatively new academic developer, I am interested in the tensions that are inherent in the field. The programmes on which I teach are designed to develop university teachers and academics, and are generally aimed at new lecturers, PhD students who teach (Graduate Teaching Assistants), and some more experienced staff looking for continuous professional development. As with many other academic developers, my route into this field was via a background in another discipline – in my case therapeutic movement education. Examining this embodied approach to education led to the development and use of a mosaic of phenomenological research methods (Leigh, 2012), and more recently an interest in how a more embodied approach might impact on developing effective reflective practice (Leigh & Bailey, 2013; Leigh, 2016). This study was brought about by my desire to bring my research into my work, and used phenomenological research methods to explore the perceptions of programmes for academic development and thus throw light on the expectations and tensions that are present for academic developers, and for me in my new role.

The drivers for academic and professional development, such as the marketisation of Higher Education (HE) (Williams, 2013), continue to lead to tensions between the desire to show competency and accredit teachers, with an intention to develop academics to achieve their full potential. Programmes to develop university teachers are found within most universities in the UK, and are becoming commonplace in many other countries (Gibbs & Coffey, 2004). Professional development within academia at large is often aimed at early career academics, and forms part of an induction/probation period that commonly lasts for one-three years. However, despite a lack of systematic programme evaluation (Kreber, Brook, & Educational Policy, 2001, p. 106), it has been suggested that such programmes “could act as educational counterweights to departmental cultures that might not take teaching seriously” (Knight, Baume, Tait, & Yorke, 2007, p. 421), although this presumes that these programmes focus primarily on teaching and learning. Some programmes also focus on other aspects of academic development such as becoming a good researcher and research supervision.

There have been calls globally for the teaching in universities to be improved (Knight, 2006; High Level Group on the Modernisation of Higher Education (HLGMHE), 2013). In the UK, for example, professional expectations of academics have changed considerably through the introduction of a series of initiatives such as the current context of reporting numbers of qualified teachers to the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HEFCE, 2013), the proposed Teaching Excellence Framework and the Higher Education Academy’s (HEA) UK Professional Standards Framework and Fellowship applications. Many ‘learning to teach’ courses were set up in the UK after the so-called Dearing Report (NCIHE, 1997). Previous to that time, provision for teaching in HE had been inconsistent and tended to be confined to non-university sector institutions that focused on teaching (Fanghanel, 2012). The HEA in the UK reported a variation in the ways that departments saw the role and focus of programmes for academic development (Prosser, Rickinson, Bence, Hanbury, & Kulej, 2006). They acknowledged that the relationship between generic aspects of teaching and learning and discipline specific aspects was problematic. They also acknowledged the pressure that completion of such programmes placed on early career academics. Prosser and colleagues (2006) reported that accredited programmes helped to raise the profile of teaching generally, and ensured that new staff thought about teaching as well as research. In support of this approach, in New Zealand a report on the early career experiences of academics found that early career academics who had completed a teaching qualification had a higher research output than those without (Sutherland, Wilson, & Williams, 2010). Also in New Zealand, a synthesis of research conducted by Prebble et al (2004) concluded that good teaching has a positive impact on student outcomes, and that academic programmes for staff development can assist teachers in the improvement of their teaching.

The nature of what comprises programmes for development has changed substantially since the 1970s (Gibbs, 2013). However, new expectations for teaching standards are not the only changes of relevance. The pressure of staff to publish at increasingly high levels is considerable. Bodies such as the HEA have a vested interest in promoting the development of teaching practices within the academy (HEA, 2013), whereas organisations such as Vitae exist to promote the development of research and researchers. If a ‘good’ academic combines both teaching and research, then it could be presumed that a ‘good’ course is similarly weighted (Van Schalkwyk, Cilliers, Adendorff, Cattell, & Herman 2012), however this may not be the case. Though foci on courses may include developing as a researcher and other academic skills, the emphasis is often specifically on learning to teach, as can be seen from the names of many of the programmes on offer. Many academic development programmes are explicitly named Post Graduate Certificates in Teaching in Higher Education, or Post Graduate Certificates in Learning and Teaching, for example at Liverpool, Brighton and London South Bank Universities. Other institutions run programmes with names such as Post Graduate Certificate in Academic Practice (PGCAP) e.g. Plymouth University or Post Graduate Certificate in Higher Education (PGCHE) e.g. at the University of Kent.

As some have pointed out, Wittgenstein, Russell, Darwin, and almost every important thinker of the past would not be submissable to the RAE/REF due to insufficient output. These changes that have been demanded of HE and its academics confronted by existing expectations to produce scholarly work, creates an ‘essential tension’ (i.e., a tension that is a necessary consequence of the situation). Academic developers could be seen as mediators for helping HE and its academics deal with this tension. As a result, there may be pressures on academic developers to provide programmes that fulfil the needs of the participants, and conform to these institutional and external drivers. In addition, they have their own academic and professional needs and goals. This has implications for individual academic developers as well as the programme content, structure and purpose of a course. There is an ongoing need for scholarship about what comprises academic development and what it is to be an academic developer, given the differing expectations from individuals, institutions and other interested parties (Healey, 2012). This too has implications regarding the content for academic developers (Bamber & Anderson, 2012; Budge & Clarke, 2012).

This paper reflects my growing interest in the development of HE professionals as I step fully into the identity of an academic developer and HE researcher. It explores the perceptions of eight individuals, academic developers and students, who are involved with or participated in a programme of academic development within one university in the UK.

For this study I chose to take a phenomenological approach to explore how the participants make sense of their personal experiences of their world (Smith, 2008). Phenomenology is that form of enquiry concerned with the nature of human experience, and is a rigorous qualitative approach used to study everyday human activities and experiences (Leder, 1990; Merleau-Ponty, 2002). As such, it is a methodological approach that is congruent with my background in therapeutic movement education. (Therapeutic movement education, or more precisely somatic movement education is “the educational field which examines the structure and function of the body as processes of lived experience, perception and consciousness” [Linden, 1994]. It can incorporate developmental movement patterns, the emotional content present in movement, the physiology of the body and the words in which we speak of and process movement [Bainbridge-Cohen, 1993]. The impact of this on my work as an academic developer is the subject of a forthcoming paper.)

The research questions included:

In its application this method has similarities to interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), which is a method that looks to explore how the participants make sense of their personal experiences of their world (Smith, 2008). IPA has roots in phenomenology and hermeneutics. Smith (2011) describes IPA as a double hermeneutic, as the researcher is trying to make sense of the participant trying to make sense of their experiences. IPA is a methodology that urges researchers “to listen and understand…collaboratively with researcher and participant. It urges us to trust” (Todorova, 2011). IPA, like other qualitative research, values individual subjectives and voices that may otherwise be ignored or silenced.

Ethical clearance was obtained following a full ethical review process. I conducted long semi-structured interviews with each participant, lasting between 25 minutes and 1_ hours. The interviews were conducted phenomenologically, starting with the particpants’ stories of how they came to be involved within the programmes. The interviews were wide ranging, and to the most part followed the participants’ interests. The data were collected and analysed, again from a phenomenological perspective (Pollio, Henley, & Thompson, 1997). The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and analysed using nVivo. I immersed myself in the data, committing to understanding and interpreting the participants’ experiences. This approach uses reflection of experience to give meaning. A systematic reflection extends the shared understanding of meaningful experience. A narrative approach to data analysis has the “power to reveal the embodied experience” (Stephens, 2011, p. 62). Like other qualitative research, this values individual subjectives and voices. The interpretative process is transparent in the narrative write-up of findings that follows.

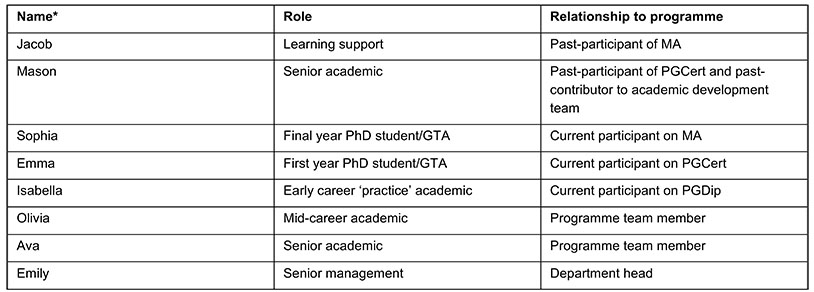

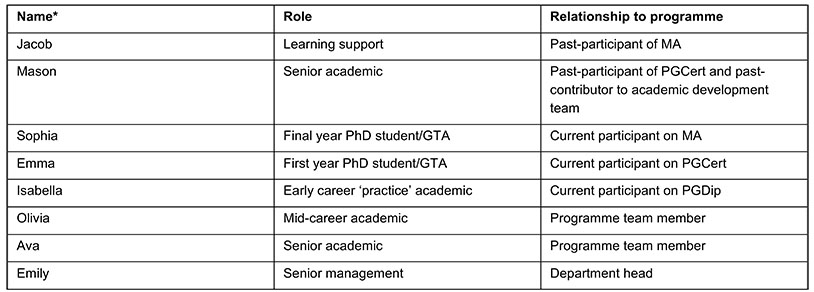

Eight individuals (six women, two men) were interviewed from one mid-size university in the South East of England that provided a post-graduate course in Higher Education, at certificate, diploma and masters level (PGCert, PGDip and MA). The participants were chosen to represent a cross-section of parties with an interest in the academic development programme, including students new to the programme, students who had chosen to take their studies further onto the Masters degree, and both junior and senior members of staff. The sample was a sample of convenience. The participants ranged in age from early twenties to late fifties. The members of the academic development team were Ava and Olivia. Emily was the head of the department in which the team was located. Sophia and Emma were PhD students and worked as graduate teaching assistants (GTAs). Sophia was near to completion of the MA, whereas Emma was in her first year of the PGCert. Isabella was a current participant of the PGDip, and a relatively new academic on a teaching and scholarship contract. She self-identified as a ‘practice-academic’. Mason had completed the PGCert many years ago, and had at one time been seconded to the team to assist with observations and the like. Jacob held a learning-support role and had recently finished the MA.

*The names have been changed, and were taken from the most popular baby names in the U.S. 2014.

Table 1 Participant names, roles, and relationship to programme.

This paper focuses on three main themes from the interviews: the importance of a holistic academic programme; the motivations for taking part; and the impact and value of participation as a route into the academy. For the academic development team this appeared to be understood through knowledge of the history of such programmes and the evolution of the current offering, whilst the participants talked about the holistic nature of the course within the context of their academic practice. Institutionally, the current and past participants believed that the impact of the programme was the improvement of teaching for undergraduates, through networking or through ensuring that all teachers were adequately qualified. However, they spoke about how they used the programme to position themselves within academia rather than purely about learning and teaching.

Teaching has historically been a major focus of academic and professional development. The course on offer at this university was felt by the team to be holistic, that is, it had a broader base than a pure focus on teaching, but incorporated other aspects of academic practice such as teaching, research, supervision and critical views on HE policy. This was intentional as far as Emily was concerned.

I still think there’s probably opportunities for us to be even more linked within the discipline and more research focused, because I would prefer to go that way than draw it back squarely into teaching, I would resist any sense of just doing teaching because I would think that would be a retro-grade step. (Emily)

Emily felt that it was imperative for the programme to offer opportunities that would allow participants to shape their future development and career. The ‘gap’ between teaching and research may be closed by participation in a programme that emphasises the importance of teaching and scholarship along with other aspects of academic development (Matthews, Lodge, & Bosanquet, 2012), and accredited programmes have the potential to raise the profile of teaching within the university, and to ensure that new staff focus on teaching as well as research as they build their academic identity (Hanbury, Prosser, & Rickinson, 2008). However, anecdotal evidence supports the idea that it is research that is vital for career development, and not teaching (Prondzynski, 2014).

Ava agreed that the basis of the programme was broad, and didn’t focus exclusively on teaching and learning. She went on to say:

I think the fundamental purpose of the programme is actually much fuzzier…it’s about helping people grow and develop in confidence and in skills and in capabilities and helping them be more active in the ways in which they plan their own careers, their own trajectories and to pursue their own interests. (Ava)

Mason said that the current offer was holistic in that it catered for all elements of the academic career. “It is almost embracing academic life” (Mason). This view was reiterated by Olivia.

That kind of helps students I think make sense of what’s going on, you know, why the students behave as they do, why do they think as they do, why are there pressures or tensions between research, you know, the pressure to be a great researcher, the pressure to be a great teacher, the pressure to be fantastic at administration, you know, and how can one person be expected to juggle all of these different roles, and why should one person be expected to juggle all of these different roles? And I kind of think, sometimes, just having that level of understanding, kind of makes things make a bit more sense, and enables people to have a bit of a better understanding of why things are the way they are. (Olivia)

This perspective was certainly appreciated by the current and past participants who were enthusiastic about this nature of the course.

It has given me the opportunity to see higher education from the inside and given me a more open perspective of things and better understanding, especially because I am from a foreign country so I understand how things work here and you know…like I felt…I can do better in the future.(Sophia)

Similarly, Emma appreciated the opportunity to learn about the entirety of the academic experience and not just how to teach. She talked about the best things for her in the programme.

Knowing about the academic world in a bit more depth, I mean…at the same time learning about the academic environment is also important you know there’s another dimension that even I haven’t considered and it’s terribly scary…I think if you’re just starting out its very important. I mean I didn’t have a clue about what was happening in academia…It’s also sort of given me a level of understanding of lecturers and the pressure they are under; I think it’s really valuable. (Emma)

The members of the academic development team shared the tensions that were always present in student feedback from the programme, with some wanting more of an emphasis on practical teaching, and others appreciating the focus on wider academic practice.

The current and past participants of the programme were all asked to speak about why they took part. The PGCert was a requirement for new probationary lecturers and some Graduate Teaching Assistants (GTAs). However, participation in the PGDip or MA was not mandatory for any member of staff and at the time was not linked to promotion requirements. For Isabella, it was very much about developing her sense of academic integrity, about seeing herself in a new role having come from a professional background into HE teaching. To her, participating in the programme was more than just about learning how to teach. She self-identified as a practice academic, and as such the programme provided her with a way to legitimise her experience (Ennals, Fortune, Williams, & D'Cruz, 2015).

Because I don’t have an academic background as I said earlier I didn’t feel very confident or like I should be here…At first I was absolutely petrified, all of the people were lovely but they had so much more academic experience than me. (Isabella)

For Emma, a new PhD student and GTA, the teaching was very much her initial focus. “It’s about learning to be confident as a teacher, learning that you need to be proactive, responsive, responding to the discipline, to what’s happening in the external environment”. She was keen to learn about the theory of learning and teaching, unlike older, more experienced academics who often eschew teaching focused development (Deaker, Stein, & Spiller, 2016). Jacob, working in a student facing role as a learning supporter, echoed elements of both Isabella’s and Emma’s narrative. He saw the programme as an opportunity not only to learn about teaching, but to credentialise himself with the academics he worked with.

I thought it would really add to my role and strengthen what I could do here. And perhaps I was somewhat self-conscious…I had more contact with academics and I think that self-consciously I was thinking how can I give advice to these people.(Jacob)

However, programmes for academic development have not always been well received. Uncertainty and dissatisfaction with such provision in HE led to a study conducted on the effect of post-graduate certificates led by Knight (2006). The findings indicated that although they expected participation in such courses to be positive, their responses were less positive after completion. This view was shared by Emily.

I think initially staff were very anti doing any sort of training. Saying that, you know, “we’re highly qualified, we know our research, we know our business, why do we need to be taught”. So there was a very negative culture…People felt that the [programme] was something done ‘to’ them rather than ‘for’ them, that would be the best way I could describe it. (Emily)

However, the programme was not always seen in a positive light by all departments. As a new academic, Isabella was obliged to take it as part of her probation, though she did not always feel supported by her department, “it was seen…as a bit of a drag and you’re not really encouraged to do it, it’s a case of “you’ve got to do it for your probation” or “you won’t enjoy it”. She continued to say, “I have enjoyed it so it’s strange that perception is there that it’s this sort of thing to do that you don’t really want to do”.

In Australia, Matthews et al (2012) investigated early career academics’ attitudes to research and teaching, and whether participation in an educational or academic development programme affected their perceptions. They found that academics at research intensive universities were less likely to engage in development activities that were aimed at improving teaching, and were sometimes discouraged or even prohibited from completing formal qualifications (ibid.). Institutional initiatives in support of teaching need buy-in from the bottom up in order to be effective (Partridge, Hunt, & Goody, 2013).

The academic credibility of the programme was also important to Olivia. The continuation of academic rigour was vital to her continued confidence in the programme, and she shared concerns over pressures to credentialise HE teachers and conform to external expectations of what academic development should be. She felt that a programme that centred exclusively on teaching and learning would struggle to have academic credibility. “We have negotiated these tensions between the kind of the national expectation of what we should do i.e. that kind of, credentialising and rubber stamping bit and the kind of belief of our course that there should be some kind of academic underpinning to it” (Olivia). Similarly, Ava commented on the need for credibility from the academic participants. In the eyes of Ava, Olivia and Emily, the academic rigour of the programme underlined its content and approach, defining its purpose as ‘academic’ rather than ‘professional’ development. They believed that in part this was due to delivery by a team of active HE research academics. This need for academic developers to be active HE researchers is not always seen as a positive thing (Gibbs, 2013). There is, however, arguably a need for research driven practice within academic development as in any other discipline (Clegg, 2009).

The impact of an academic development programme was felt on at least two levels–individually and institutionally. For Isabella, it was about positioning herself within her school, first as a sessional teacher, then as an academic. “It was a stepping stone, it was my foot in the door and I worked incredibly hard and got a very good reputation very quickly which was very lucky” (Isabella). Likewise for Emma, participation in the course gave her the leverage she needed as a PhD student to be allocated teaching. “For me it was just getting started and just having the foot in the door to be doing it” (Emma). Sophia spoke explicitly about her future career and possibilities of publishing within the field after she had finished her PhD.

At the beginning I did it just for teaching to be an effective teacher. Now…I’m doing it for part of my career development and I don’t think I will stop here to be honest. I think I would like the idea of doing some publications and getting involved into the issues you know. (Sophia)

Jacob also spoke of longer term effects “it’s been very much a spring board that has kind of hopped me off into a different direction, but at the same time it has helped my ongoing role…it has made me more critical of different approaches to higher education research” (Jacob).

The current and past participants of the programme spoke about how they had or were experiencing its impact on themselves. However, they also spoke about how they used the programme to position themselves within academia rather than purely about learning and teaching. They believed that for the institution, the impact of the programme was to improve the teaching for undergraduates, through networking or through ensuring that all teachers were adequately qualified. “I don’t know whether it is just a tick box to validate people, you know you’ve done your PGCHE so that means you are a qualified teacher. I hope it’s more than that” (Isabella).

Within the academic development team, the feelings were mixed about why individuals and indeed the institution would want staff to complete the programme. Olivia agreed that it might be “a possible route for them to legitimise themselves within the academy”. Emily believed that “the institution wants to be confident that they have competent teachers, that they’re not going to put somebody up there that’s going to make a real mess of it”. Olivia was much more instrumental or pragmatic, “one way of cynically looking at it is that it’s a credentialising process”. Mason was optimistic about the use of academic development programmes. Institutionally he felt that it was of such use that he thought such engagement should form part of the promotion requirements.

They do get knowledge about topics that they haven’t heard before. They get the opportunity to network with a lot of other people outside their immediate discipline. I would hope they will find out that other people have exactly the same problems so they are not completely on their own with all the, say psychological issues as for example a lot of people think ‘I am a fraud I shouldn’t be here’. They get the opportunity to focus some of their time on say reflective practice (Mason).

Ava agreed that the basis of the programme was “the development of people in the various roles in which they are” (Ava). Mason continued to say that the current offer catered for all elements of the academic career. Similarly, Emma and Sophia appreciated the opportunity to learn about the entirety of the academic experience and not just how to teach. As such, the programme offered them a kind of continuous professional development, but by accessing it via an academic programme delivered by academics, they were able to make sense of it in a way not open to those attending programmes offered by human resources departments for example (Mackay, 2015).

In addition, the opportunity to network, to create collegial communities and communities of practice was commented on by most of the participants, whether this was between individuals sharing experiences for the first time, or drawing on and connecting those with varied backgrounds.

They need to bring academics together so there is this maybe idea that academics should work closer together and this will be better for education for all…I think this is the major contribution of the program, and sharing experiences with other members of staff who have been around for many years it’s a good indication of how to deal with stuff. I think it’s a way to feel that they are part of a community, they can exchange ideas, they can contribute(Sophia).

This richness of experience was seen as a positive for all the members of the academic development team. The idea of becoming part of a community of practice, and the importance of such was expressed by all participants in this study. The value of communities of practice in HE have been widely reported e.g. to develop learning and teaching practice (Ryan, 2015) or to explore fields of study (Tight, 2004). The programmes were seen as a place where participants on the programmes could reflect and process their academic practice in a collaborative way which could act as a counterbalance to the performative, competitive nature of today’s academia (Kennelly & McCormack, 2015). The importance of such communities for the individual, often isolated academic should not be underestimated (Charteris, Gannon, Mayes, Nye, & Stephenson, 2015).

To date, the programme offered has been an holistic approach to academic development, and not one that focuses solely on teaching and learning. This approach thus better reflects the entirety of academic work (Malcolm & Zukas, 2009), and is more likely to support staff to become research active (Sutherland et al, 2010). Not all participants wish to complete a programme of development, of those that are mandated to do so not all will embrace such a programme positively (Trowler & Cooper, 2002). However, those staff who perceive the provision of support and training to be effective are more likely to be satisfied overall (Sutherland et al, 2010).

While a theoretical understanding underpinning practical knowledge can support new teachers (Sadler, 2012), it must be noted that the impact of such programmes is not entirely due to the content, but also has to take into account the agency of the participants, as this will have a large amount of significance in how they choose to develop their practice (Kahn, 2009).

I was explicit about using this paper as a transition into a new post as an academic developer and HE researcher, and the topics under investigation reflected both the priorities of my new workload and my personal motivations as an early career researcher. There are, at present, no formal systems for developing academic developers, although there have been calls for a review of how newcomers to the field are inducted (Quinn & Vorster, 2014). Academic developers can be employed on academic contracts, or administrative/service contracts, with correspondingly different workload expectations (Fraser & Ling, 2013). It seems to me that whilst academic developers do not have to be employed as research-active academics, there is an element of credibility to be addressed, in that they are generally looking to teach and develop academics. Academic developers who are also academics can potentially act as role models, can be expected to have an understanding and empathy for their students’ situations, and to understand the essential tension of balancing teaching and research that faces all academics today.

There is a danger that courses or programmes run or taught by non-academics will focus on the tools, techniques and tips of teaching, the competencies of the trade, rather than the holistic development and induction of academics into the academy as a whole. There is a discourse around the role of an academic developer, and whether their work should be to develop the academic holistically, or to focus more prosaically on learning and teaching (Golding, 2013). I will continue to develop my HE research along lines that are congruent with my work as an academic developer. I want to be able to be credible with the academics with whom I work, and believe in the programmes I deliver, and have them be useful to the individual participants rather than only be a credentialising process. I believe that this is a discussion that is relevant to the wider academic development community. I feel that the experiences of academic developers as researchers, and the tensions inherent in their identity as academics are relevant to this ongoing discourse.

Jennifer Leigh completed doctoral studies exploring how children perceived, expressed and reflected on their sense of embodiment through movement. Her research interests include embodiment, reflexivity and phenomenological research methods and how these relate to academic practice and academic identity as well as aspects of teaching and learning in higher education.