Angela Green, Ian Richards, Susan Smith, Leeds Beckett University, UK Ibrahim Hussain, Assiut University, Egypt

Curriculum design has received critical attention in the Global North, and much research has been published around the key principles of good curriculum design (Cousin, 2006; Meyer & Land, 2003; Killick, 2006; Gibbs, 2010; Baume, 2009).This is linked to the growing trend in curriculum renewal and internal and external quality assurance processes. In the UK, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) state that higher education curricula are reviewed and refreshed every four-six years (QAA, 2014). The process ensures that programmes of study are holistically evaluated, that learning outcomes are valid and being met and that quality standards are confirmed by independent external bodies. Despite such demands, there are no specific rules on how this should be carried out, but there are many examples of good practice cited in the literature. In 2012, Leeds Beckett University (LBU) underwent a major curriculum refocus where all UG programmes were refreshed and reviewed. In order to provide an underpinning structure to this developmental process, the Centre for Learning and Teaching reviewed the literature on curriculum design and created a set of nine guiding course design principles for staff to use. This paper initially reviews the challenges and benefits of embedding the design principles within the Sport Marketing UG degree at LBU. It then evolves and begins to explore the challenges that arise when transferring these principles to international contexts and in particular the Egyptian higher education system.

Rapid developments with international activities linked to universities in Egypt illustrate a diversity of new collaborations in the new millennium (Altbach & Knight, 2007). However, this activity decreased in the aftermath of political events in Egypt in 2011 and LBU was appointed as key partner in the International Inspirations University Links Programme in Egypt with one of its key aims being to reverse this trend. LBU was appointed to assist the Faculty of Physical Education at Assiut University to develop the first Sport Marketing degree programme in North Africa. International Inspirations was London 2012’s sport legacy programme, delivered by the British Council in partnership with UNICEF, UK Sport and the Youth Sport Trust (British Council, 2014).

The partnership involved staff from LBU visiting Egypt to coordinate a two-day workshop on curriculum design and delivery. This was attended by 15 members of the Faculty of Physical Education who had either subject-specific knowledge or responsibilities for curriculum development. These ranged from Associate Deans to newly qualified lecturers and graduate teaching assistants. The interactive workshop facilitated by LBU staff introduced key concepts and processes that had been developed as part of the LBU curriculum refocus and was supported by translators. This type of workshop was similar to the preparatory workshops delivered at LBU for staff in preparation for curriculum reviews with an ethos of encouraging participation and facilitating discussion around key concepts. This process and key ideas that underpinned the workshop were a new way of thinking and working for colleagues from Assiut. At the time, Sport Marketing provision at Assiut was limited to a couple of modules that provided a basic general overview of marketing principles, rather than in-depth, specialist Sport Marketing modules around, for example, sponsorship and digital media. This appears to represent the construct and structure of all sport-related degrees in Egypt. Colleagues at Assiut had identified the need to develop more specific and specialist provision in Sport Marketing as a key area for development to meet the needs of the labour market and the growing sports industry in Egypt. Indeed, both LBU and Assiut University were similar in that they were the first academic institutions in their respective countries to create degree programmes in this particular field of study.

The case study of this collaboration reflects on the experience of developing a curriculum within the confines of another university’s regulations and national frameworks. It also explores the challenge of cross-cultural shared understanding and cooperation. The paper contributes to the existing knowledge on curriculum design by providing a cross-cultural focus and illustrates some of the challenges inherent in embedding LBU’s key course design principles (Leeds Beckett University [LBU], 2014).

The Sport Marketing degree programme at LBU was one of the first UG degree programmes of its kind in the UK and was initially designed and approved in 2005. It was born from the need of a sports industry to create graduates with specific expertise in marketing, but who also understood and could adapt to the challenges created by the unique nature of the sports industry. There were numerous degrees in marketing in the UK, but few that focused specifically on the sport context and provided graduates for a buoyant and rapidly growing market. Global spending on sport was increasing and European revenues were rising at a faster rate than GDP, and had grown by 6% each year since 2000 (Collignon, Sultan, & Santander, 2011). The course was developed to take advantage of this niche but growing market. Like all LBU courses, it has since undergone significant review to ensure the course was still relevant and current and met the needs of the sector, the students and the sports industry. During each of these reviews, some major changes have taken place, the most notable being the need to embed more modules which focused on developing digital marketing skills to reflect the significant change in the marketing industry in its increasing use of social media and digital technologies. This has resulted in a need for UK graduates to be more knowledgeable in these areas (Dennis, 2014).

Following significant research and consultation, the University decided to implement a mass review of its courses and provided guidance on how course teams should evaluate their provision and inform future developments. Course principles were implemented university-wide for all courses as part of a major curriculum refocusing activity. They were designed to underpin and improve the consistency and quality of learning in all UG and postgraduate (PG) courses. They were based on evidence which explored excellence in curricula, best practice and effective course design. Developmental feedback to staff about the principles ensured that courses going to approval had clearly embedded them in the course documents, delivery and practice. A pan-university academic group generated nine principles to embed in the courses. The principles were honed by each course team to suit each discipline. The principles are thematically grouped but closely interrelated and allow teams to think holistically about the nature of course design. This case study focuses on five of these concepts:

(A) Key concepts

(B) An inclusive environment

(C) Depth of learning

(D) Vertical and horizontal integration of learning

(E) Challenging and authentic tasks

The remaining LBU course principles were i) a strong course identity ii) personalised student support iii) course assessment strategy iv) activities linked to the student experience. These were more robustly embedded and delivered at Assiut with a good staff understanding of their applicability. As such, the principles (A-E) are prioritised for discussion in this paper, as they were the most relevant for academic staff. This case study paper examines the course principles (A-E) and their application at LBU. It will present some of the research findings that support the need to embed such principles and will reflect on how these have been implemented at the University. In addition, it will comment on the challenges and practicality of embedding such principles into the creation of an UG Sport Marketing degree course at Assiut University.

The term threshold or key concept was first conveyed by Meyer and Land (2003) in a UK based research project, designed to identify factors that lead to high quality learning environments. They presented the view that certain ideas are held to be central to the mastery of a subject and these are known as the threshold or key concepts.

The challenge for course designers is the need to identify which concepts are key for the mastery of their specific subject area. This has a tendency to generate significant debate amongst course teams, particularly in degree programmes that are multi-disciplinary. Cousin (2006) argues that by making sense of what is central to understanding the subject, it is possible to reduce the problem of having a “stuffed curriculum” (p. 4) where there is a tendency to just transmit vast amounts of knowledge. In contrast, the key concept approach encourages course designers to define what is fundamental to the subject. When defining key concepts, a further challenge for vocationally oriented programmes is meeting the requirements of industry accreditation agencies and of QAA subject benchmarks. In the UK there are no benchmarks specifically for sport marketing or the wider area of sports business, therefore curriculum designers working in this area have to draw upon benchmarks from both business and sport. This has some challenges, as the sport benchmarks are focused primarily on sports science and physical education.

During the curriculum review at LBU, the Sport Marketing course development team created a programme that drew on specific sport marketing themes and disciplines. This included sport marketing, branding, sponsorship, digital marketing, sport consumer behaviour and strategic sport marketing and planning. It also included principles from the more generic business disciplines and philosophies which included: management, leadership, event management, economics and globalisation. The course was also designed to meet the accreditation requirements laid down in the UK by the professional body for marketing, the Chartered Institute for Marketing (CIM). This body is an internationally recognised body and also operates in Egypt.

In Egypt there was a lack of appropriate subject benchmarks and few recognised accrediting bodies. This was the first sport marketing degree to be developed and the academic team were drawn primarily from a physical education background. The idea of creating and embedding key concepts appeared to be a new one to many of the workshop attendees. However, this created a useful blank canvas for the educators to think differently about developing a course using an approach that was new to them and they generated a contextually relevant set of key principles. What was particularly striking to the LBU staff facilitating the workshop was the innovative and novel key concepts that emerged. For example, a key concept agreed by the Assiut team was moving beyond knowledge-based concepts to emotional and psychological concepts. This was an area that had not previously been considered by LBU staff. It will be fed forward into our (and Assiut’s) future curriculum reviews. This is a good example of the benefits of international and cross-cultural working in reverse learning for UK staff engaging in international projects.

A key LBU course principle is the need to create an “inclusive learning environment”, a place where all students can choose to be visible, valued, and respected for their individuality and can engage in respectful discussion and collaboration with others. From an organisational perspective, it is also about recognising difference and accommodating and meeting the needs of all of the institutions’ learners (LBU, 2014).

In relating these principles to the reality of course design, LBU courses try to ensure that all course materials and activities represent a range of cultural perspectives and practices. In addition, a conscious effort is made to provide for the differing learning and assessment preferences across the student body.

Our aim in Egypt was to only open a discussion about assessment variety and the nature of inclusive curricula and not to force or implement change in a culture traditionally used to a more limited assessment range.

Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) have suggested that assessment modes should be selected to enhance student learning where tasks are varied and authentic, formative assessment is strong and expectations are made visible to the students as far as possible. Race (2009) suggests that using a broader range of assessment methods is an inclusive approach to assessment design giving more students more opportunities to demonstrate their learning in different contexts. It also helps not to disadvantage those who dislike one method of assessment in particular and it encourages students to use different talents and to utilise a range of learning styles. At LBU, it is mandatory for course teams to show that assessment methods are varied. This may include essays, posters, case studies and presentations. A matrix is created to map assessment types across the three years of the programme to ensure one method does not predominate over others.

When discussing this idea with Egyptian colleagues, they found Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick’s (2006) concepts challenging and somewhat unsettling. The most common forms of assessment for students in Egypt are attendance, quizzes and oral or written examinations (European Commission, 2010). However, educational assessment in Egyptian higher education is not dissimilar to many other countries in the world in that there appears to be a dominance of traditional exam-based assessments. This ideology is deeply rooted in primary and secondary education where students have to pass exams to progress, and those with the highest grades are given good government jobs (Hargreaves, 1997).

Researchers have debated the need to create a curriculum design that encourages a deep approach to learning rather than a surface approach (Biggs, 1999; Ramsden, 1992). The key distinction between deep and surface learning is that with a deeper approach to learning students aim towards real conceptual understanding, whereas surface learners focus on passing exams and tests by learning facts rather than fully understanding concepts (Houghton, 2004). Hargreaves (1997) has commented that the educational system in Egypt is oriented primarily around examination and memorization of facts in the classroom. Houghton (2004) identifies a number of key considerations in designing a curriculum to build deep learners. These include:

Looking for meaning rather than relying on rote learning

Focusing on the central argument or concepts to solve a problem rather than on the formulae needed to solve it

Active as opposed to passive interaction

Making connections between different modules rather than treating modules as separate entities

Linking course content to real life

Ensuring plenty of time for key concepts to be fully understood and applied

Using assessments that require thought and ideas used together rather than assessing for independent facts (e.g. using short answer questions)

Relating new material to what students already know and understand as opposed to trying to cover too much material at the expense of depth

In considering these, it was necessary to examine whether there was a need to reduce content in order to achieve greater depth of learning where deep learning relates to the level of intellectual demand. The LBU Taxonomy (LBU, 2015) was developed to help staff with the precise use of words to describe associated learning activities and to develop assessment that best reflects the level of demand of the learning outcomes. It supported staff discussion and informed ways of encouraging students to develop the core themes, engage in deep learning at each level and not just learn to pass their summative assessments.

During the LBU review it was agreed that course designers needed to move from a curriculum with eight modules to six. By spending more time on fewer modules, it would be easier to engage more deeply within that module. If more participation is involved, engagement is increased (Kuh, 2009). The Sport Marketing course team found it difficult to decide which modules to remove and which would be the focus of the new course. The students and industry were consulted to help inform the final process. For Assiut staff, this type of approach was more problematic. They were familiar with a structure that saw students completing 18 modules at every academic level. To move to a course with only six modules at each level was impractical as they needed to adhere to their National Framework. The final programme for their four year course, whilst a significant shift in itself, resulted in 10 bespoke Sport Marketing modules in years three and four preceded by the general programme of 18 modules in the first two years (Assiut University, 2004). The opportunity to introduce shared modular summative assessments to enhance coherence and facilitate deep learning was also limited due to their assessment framework.

At LBU, when designing the curricula, distinct themes of study were created vertically (i.e. up through the undergraduate academic levels from first to final year) and thought was given to how the depth of learning could be strengthened at each level. Staff still perceive this as a challenge, despite having only six modules per level compared to the 18 per level at Assiut University. The LBU Undergraduate Taxonomy of Assessment Domains (LBU, 2015) based on the original work of Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill and Krathwohl (1956), helped inform course design which focused staff on considering the precise range of skills which needed to be strengthened at each level for each identified theme.

For example, first year LBU students take an introductory skills-based digital marketing module; second year students develop this with one that explores the issues of using digital technology in sport; and then in the final year, a digital module examines the use of digital analytics and how big data can be used to inform the creation of digital strategies. This approach demonstrates a distinct digital marketing pathway through the three-year course, where students start by learning key practical skills such as website and blog creation, but finish using data to inform strategy and enhance their critical reflection.

At Assiut, the idea of horizontal integration of learning presented the same sort of challenges as for LBU staff. Embedding linked assessments across more than one module, a useful way of enhancing integration and coherence, was discussed but often disregarded. This was because of difficulties with assessment regulations and the notion that if a student were to perform poorly on one module, if it were linked to another it would provide further disadvantage to the student.

Within the Egyptian system, the notion of vertical and horizontal integration of learning was problematic to implement within the confines of the existing Assiut University and National Egyptian Higher Education Framework (Assiut University, 2004). At Assiut, all students are required to take a general education programme for their first two years. This currently involves studying 18 modules in a broad range of subjects that are general in nature rather than concentrating on specific subject-focused learning skills. The intention was that the sport marketing specialist elements, would then be delivered over the final two years. Whilst there are clearly economies of scale for delivering general education programmes in this format, and indeed, there are arguments against specialising too early, it means that students are not exposed to the context of sport marketing until their third year and lack early exposure to professional contexts and authentic activities. For effective learning to take place, knowledge must be taught in context (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and our own experience at Leeds Beckett has also found that where modules are related to the professional context, the students engage more fully. In recent years, at LBU, a problem was experienced where the Sport Marketing students were taught research methods alongside sport business and sport leisure and culture students. Students felt that this put them at a disadvantage as the module lacked a business and marketing focus and did not equip them fully to undertake their final year Major Independent Studies. In response, a more bespoke module was created contextualised around Sport Marketing and business. The existing Assiut framework creates similar issues for the Egyptian students who will not fully relate to the sport marketing context until the third year of their course.

A number of authors have acknowledged the value of employing authentic tasks and assessment in educational practice (Herrrington & Herrington, 2006; Mueller, 2014; Wiggins, 1990). Mueller (2014), refers to authentic tasks “as a form of assessment in which students are asked to perform real-world tasks that demonstrate meaningful application of essential knowledge and skills”. The basic idea being that we do not want students to simply ‘know’ the content of their discipline when they complete programmes of study; we need them to be able to ‘use’ the acquired knowledge and skills in the real world. Consequently, the assessments created by educators need to enable students to demonstrate that they can apply what they have learnt in authentic situations (Mueller, 2014).

Traditional assessment methods are seen to be those where students select from a range of choices, i.e. multiple choice, recall facts or match selected answers together. Authentic assessments, regarded as being at the opposite end of the spectrum, are thought to require wider application of knowledge, a degree of real challenge and a need to make connections (Newmann, Marks, & Gamoran, 1996; Lund, 1997), where students are required to think more broadly about how they will utilise and apply their learning. It is through the process of applying this knowledge that students are thought to deepen their learning (Ashford Rowe, Herrington, & Brown, 2014).

Given that a key driver for authentic assessment is to create students who can apply knowledge taught in the classroom to real-world contexts, it is not surprising that the curriculum development process has changed (Mueller, 2014). Consequently, there is now a need for the educator to work more closely with industry to identify and establish the skills that graduates require to be proficient and successful in the workplace. Once these have been identified, there is a need to create a curriculum that provides assessment opportunities to reflect them.

At LBU, all staff designing new courses and reviewing existing ones are required to work with employers to ensure that the curriculum is fit for purpose in terms of the specific industry’s needs. During the BA (Hons) Sport Marketing review, a panel of experts from the sports industry, including a commercial manager from a professional rugby club, digital managers from a professional sport club, health club managers from a commercial fitness provider and managers from leading global sport brands were all consulted on the design of the curriculum. They were provided with an overview of the curriculum and its justification, together with an outline of each of the modules, and the relevant assessment methods and criteria. Together with the course team, the panel of experts were asked to appraise the proposed programme in terms of its suitability in equipping graduates to work in the industry.

Whilst the notion of working with employers and the idea of ‘employability’ was a relatively new concept, the Assiut team were keen to develop this area. This was highlighted as a key focus area and outcome for the University Links Programme. It led to further collaborative work with LBU with an employability conference being developed and delivered in Cairo. A range of individuals from industry were invited including sports media, sport facilities managers, national sports federations, private companies and educational partners. The event was well received and provided Assiut with an opportunity to develop links with industry and use this as a springboard for creating authentic real-world tasks for their students.

The European Commission (2013) has been driving an approach to flexible delivery and the course design principles at LBU encourage course teams to adopt a broad range of teaching and learning styles for their courses to complement different, more flexible forms of course delivery (i.e. distance learning, blended learning). In Egypt, it was found that many universities used a traditional, large class lecture style of teaching, where the emphasis is on the tutor providing facts and theoretical principles in what is generally considered a passive, didactic approach (Beard, 2010). This is an environment certainly not unique to Egypt or the UK. The Sport Marketing programme at LBU has also attempted to shift to a more participatory and interactive approach to learning. This approach to learning incorporates experiential learning, where the focus is more about learning from doing and reflecting on experience (Kolb, 1984). It is in stark contrast to didactic or rote learning, where the learner is relatively passive (Beard, 2010). Clark and White’s (2010) study suggested that good quality business education programmes need to incorporate an experiential element to challenge the students. This approach is particularly relevant for vocationally oriented degree programmes like Sport Marketing.

At LBU, students participate in many types of experiential learning throughout their degree programme. For example, on the Marketing Communications module, students have to launch a new sport product to the market. They produce TV adverts, brochures, flyers and websites in order to create a professional launch and present it to a fictitious audience. The students learn how to apply the theory to real-life scenarios. In the Strategic Marketing module students create their own multiple choice questions, the idea being that if students have to create their own questions, they have to be able to understand the content much more deeply (Green, 2012). Other experiential elements include teaching their peers about the key difference between sport marketing and generic marketing in a workshop style environment. Students undertake authentic activities and assessments in their event management modules by producing a feasibility study for an event, then deliver the event and finally its critical evaluation. This participatory or experiential design is thought to encourage greater understanding of the key concepts (Ash & Green, 2009) and challenge and stimulate the students.

However, the idea of experiential learning was welcomed by the Assiut course team, who were keen to explore assessment ideas, authentic tasks and marking matrices, for what were considered novel summative assessment types. Assiut students undertook experiential learning as part of their degree programmes but this was limited solely to the teaching and coaching of sport.

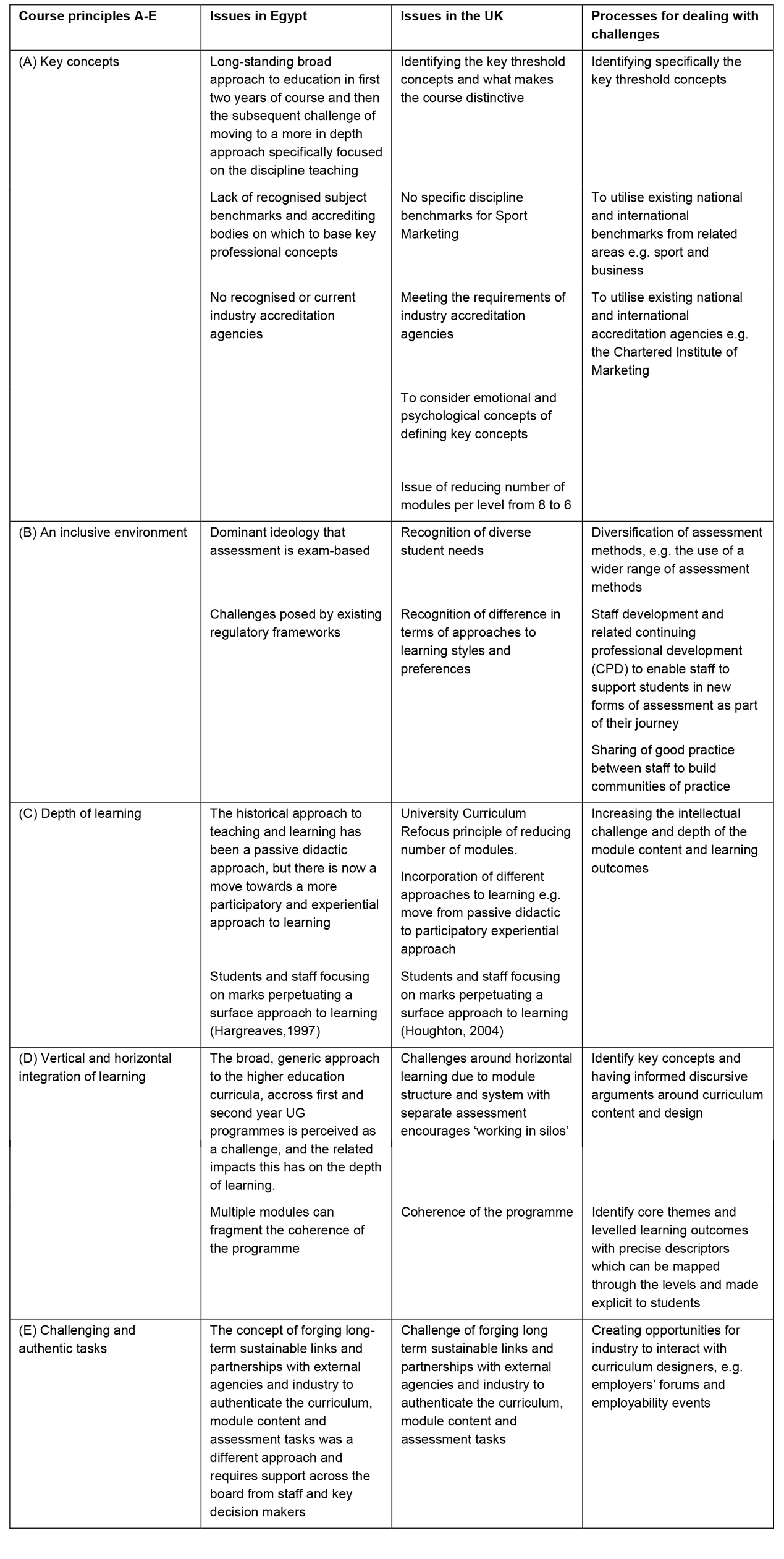

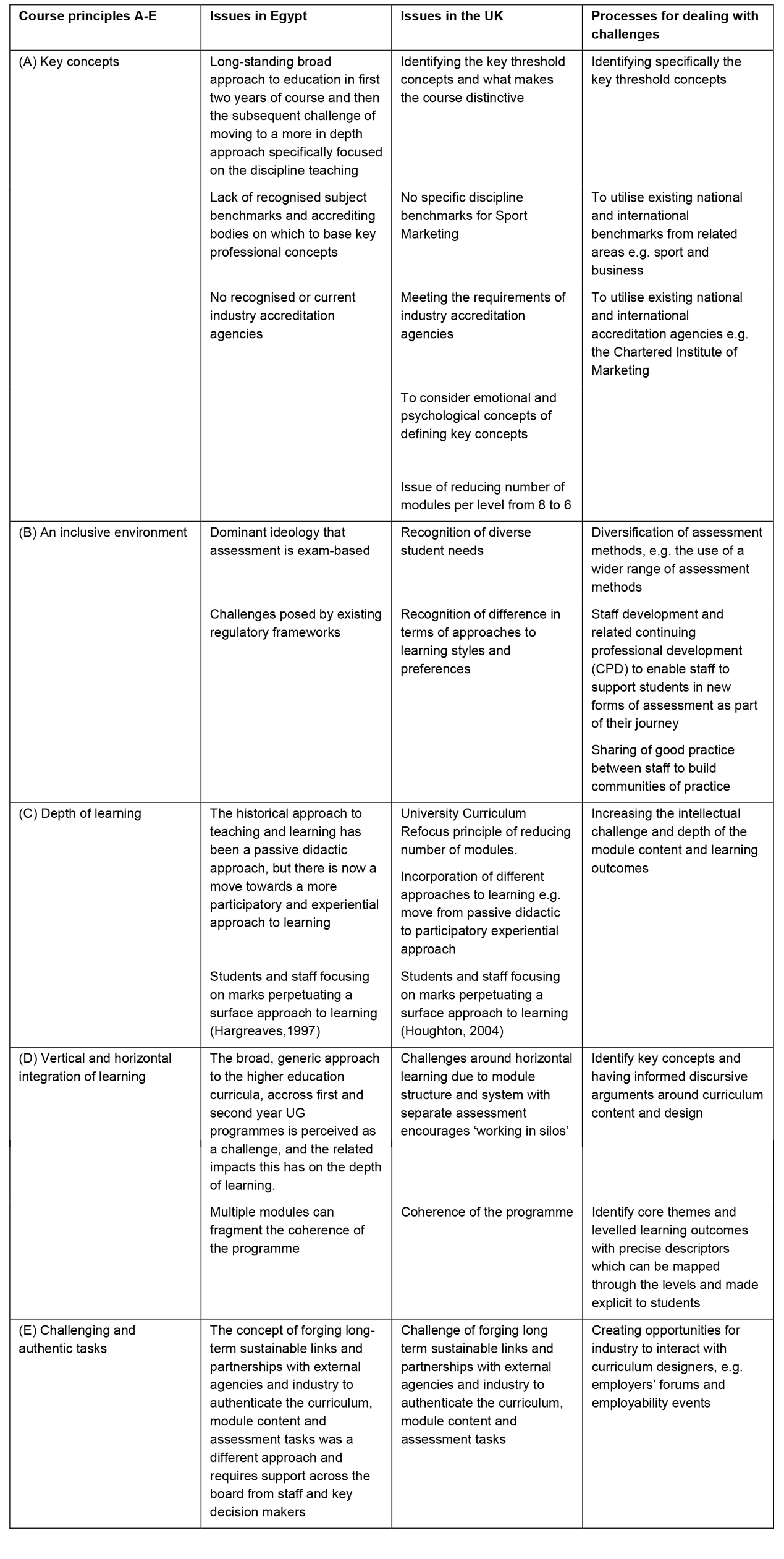

The key challenges and issues of curriculum development experienced by sport marketing academics in Egypt and the UK and the processes in dealing with them are summarised in the following table. Some of these challenges and issues were shared in both the British and Egyptian contexts, whilst others were specifically related to the contextual and environmental features of the Egyptian and British higher educational systems.

Table 1: Key challenges and issues in curriculum development in Egypt and the UK

There were many lessons learnt overall. Pre-workshop preparatory work was key, both in exchange of curricular documents and mutually understood, achievable terms of reference for both institutions. The focus of the visit was ‘ironed out’ in emails and calls in the months leading up to the visit. For example, ensuring that the translation of the workshop materials and LBU curricula were circulated to attendees well in advance. This enabled clarification over terms which did not translate directly or enabled participants to understand what specific terms meant in the context of each country. At the beginning of the workshop, clear ground rules for behaviour were generated by both groups and a clear expectation that mutual understanding of each others’ curricula would be a realistic goal even if individual institutional change did not follow immediately. Some clear measurable actions were noted and shared as part of plenary exercise.

The engagement in international and cross-cultural projects of this nature has been a valuable learning and reflective experience for all those involved. LBU principles were developed within a UK context and, as such, whilst effective in the UK may not be so acceptable or relevant in international curricular contexts. Despite this, as curriculum developers, it was particularly valuable to consider the needs and context of other academics in different international environments and initiate a positive discussion about course design. It was particularly interesting to explore the emotional and psychological elements of perceived key concepts for the subject area, one of the key principles, for the Sport Marketing discipline. This consideration of the perceptions of the discipline’s key concepts, (learnt from Assiut colleagues) has now been introduced more robustly by the staff delivering the workshops to UK colleagues who are currently in the process of undertaking Periodic Review of the LBU Sport Marketing course. Given the rapid development of activity that supports the internationalisation and globalisation of higher education, (Altbach & Knight, 2007) this area that requires further exploration which we intend to explore together in future collaborative work.