Peter Cruickshank, Edinburgh Napier University, UK

In an age of international student recruitment, there is a conflict between nominal language requirements used in recruitment, and students’ need to produce acceptable academic courseworks (for example, Richardson, 2014), there may be pragmatic advantages to retaining an exam element in module assessment.

To investigate this, international students’ perceptions of exams as an assessment instrument were evaluated in the context of a UK university’s strategies for internationalisation of its learning teaching and assessment (LTA). The particular focus was students who have taken business oriented modules offered within a School of Computing’s programmes which included modules with an exam element and a requirement for high level business English, making them ideal for investigating this area. It is important to recognise the limitations arising from the nature of the project. The research covered approximately 50 students in attendance in June 2015 (representing intakes in September 2014 and January 2015). Different intakes could well produce different results – this is particularly true in the case of the small cohorts studied here, especially as the international intake can vary significantly between years. Results are therefore more likely to be indicative than conclusive.

This area raises a number of issues around internationalisation, acceptability and effectiveness of exams in business systems/ management related subjects for postgraduate students.

In UK universities, students are grouped into three broad categories: UK, EU and rest-of-world. The last two which involve studying full time and not ordinarily resident in the UK (Hyland et al., 2008, p. 4) have been defined as international (Bartram, 2008). However, their needs and expectations can differ significantly and it is often the case that EU residents are grouped with UK students (Hyland et al., 2008, p. 4); therefore for clarity three categories are used here: UK, EU and International. International students can face a number of challenges in addition to speaking English, for example understanding process or accessing the support that is available to them (Bartram, 2008; Crose, 2011).

Internationalisation moves the focus from classifying individual students to the institutional response in terms of integrating an international dimension into a university’s activities, closing the gap between marketing activities and the “lived experience” of students and staff (Hyland et al., 2008, p. 6). Universities have long had international links, but internationalisation is understood as an institutional strategy in response to the wider context of globalisation and free trade (and in the EU to an integrationist agenda) (Altbach & Knight, 2007). In this context, internationalisation is dominated by Anglophone universities in developed countries such as the UK. From a strategic perspective, internationalisation has an important role to play in cross-cultural understanding (Crose, 2011). Given that international students are generally already adept at cross-cultural communication it has been argued that the beneficiaries of internationalisation are actually the home (UK) students (Hyland et al., 2008, p. 28), so any study of the effects of internationalisation needs to take their perspectives into account.

Universities do not always provide clear guidance to academic educators on responding to the challenges raised by internationalisation, resulting in inconsistent practice (Daniels, 2013). Indeed, academics can express cynicism about the motivations at institutional and senior management levels, with an observed low priority given to training staff, or even enabling peer support (Daniels, 2013), and a perception that the students are primarily seen as a revenue stream (see also, Altbach & Knight, 2007). The strength of actual institutional support for internationalisation is demonstrated by the allocation of resources and willingness to be flexible with assessment requirements (Thomas, 2002). A good source of evidence is institutional artefacts and processes, including their approach to sitting exams (Nelson & Creagh, 2013, p. 26). This secondary area of research will give an understanding of the constraints on any proposed solutions.

Assessment is used to refer to the measurement of students’ outputs and communication of performance to them and academic authorities (Brown, Bull, & Pendlebury, 1997, p. 8; Entwistle, 2009, p. 157), matching actual performance against what it should or could be (Biggs & Tang, 2011, p. 196). Postgraduate assessments are particularly challenging in this respect as students are expected to be researching and creating their own evaluation framework.

Issues around assessment are fairness, reliability and validity (Brown et al., 1997, p. 251). The choice of appropriate instrument can be significant; they are generally a combination of courseworks (literature review, case study or business report) and exams (Richardson, 2014), which are defined as “assessments undertaken in strict formal and invigilated time-constrained conditions” (Bridges et al, 2002, cited in Richardson, 2014).

In reviewing the literature, Richardson (2014) identifies a number of issues with exams, including the question of whether they are appropriate at all at postgraduate level; there is some indication that open book examinations can be designed to mitigate some of the issues (Myyry & Joutsenvirta, 2015). Exams do continue to have the advantage of allowing a broad range of topics to be covered (often courseworks allow the student to focus on a single topic). Finally, diversity in assessment methods is argued to be valuable in ensuring alignment with learning outcomes (Galloway, 2007, p. 6). Less used options are available, for example assessment of class participation.

The increasing use of courseworks is often seen to be a result of a move from a testing/rote learning culture to one of deeper learning (Myyry & Joutsenvirta, 2015). One argument for the use of courseworks is that the average mark of students achieved in modules assessed through courseworks is higher (and with less intra-class variance) than if exams are involved; part of the difference may be due to clarity over marking criteria (Payne & Brown, 2011), important when students are not confident of their English. The lack of experience of many students in writing longer original texts as needed in courseworks can lead to students preparing courseworks to resort to plagiaristic behaviour (Coates & Dickinson, 2012; Daniels, 2013).

Despite the use of anti-plagiarism software such as Turnitin (Stapleton, 2012; Youmans, 2011), exams remain a bulwark against plagiarism and use of essay-writing websites. However, this raises new problems: international students have been found to achieve disproportionally lower marks in this form of assessment (Schmitt, 2007, p. 2).

It follows that exams are encountered at university by international students, most of whom have English as a foreign language (EFL). The IELTS tests used for accepting EFL students include scores for a range of skills, including listening and speaking which are not normally directly assessed in an academic environment and in particular, they do not prepare students for academic writing as needed in exams (Hyland et al., 2008, p. 26; Schmitt, 2007, p. 4). Most international students are likely to have encountered examinations in their studies (HEA, 2014). However, it is possible for an international student to have no exposure to writing more than 250 or even 50 continuous words before encountering the UK Higher Education system (Carroll, 2008; Schmitt, 2007)

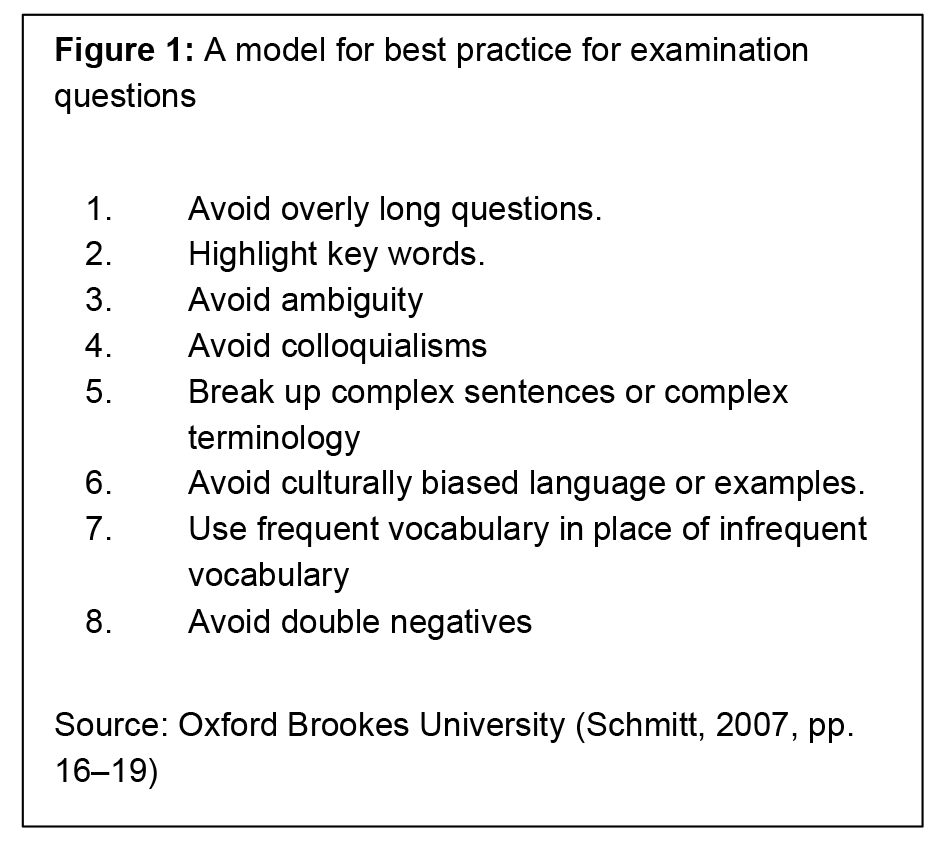

Exam timings have traditionally been based on the needs of native English speakers (Schmitt, 2007, p. 13) and high reading loads can be a particular problem (Schmitt, 2007, p. 19). Recommended best practice includes ensuring students are well prepared, that time restrictions do not impact on students (this could include additional reading time) and that there is access to reference materials (Schmitt, 2007, p. 6); a fuller list is reproduced in. There is conflicting research on whether students’ perceptions of exams is improved by allowing the use of word processors or whether they feel handwriting avoids technological risk (Mogey & Fluck, 2013, cited in Richardson, 2014)(Mogey et al, 2012, cited in Myyry & Joutsenvirta, 2015). It is more certain that exams and timed writing generally do create additional psychological pressure for EFL students, despite familiarity with the format (HEA, 2014, p. 4) so it is important to be clear that clarity not fluency is expected in answers (Carroll, 2008; Schmitt, 2007, p. 25)

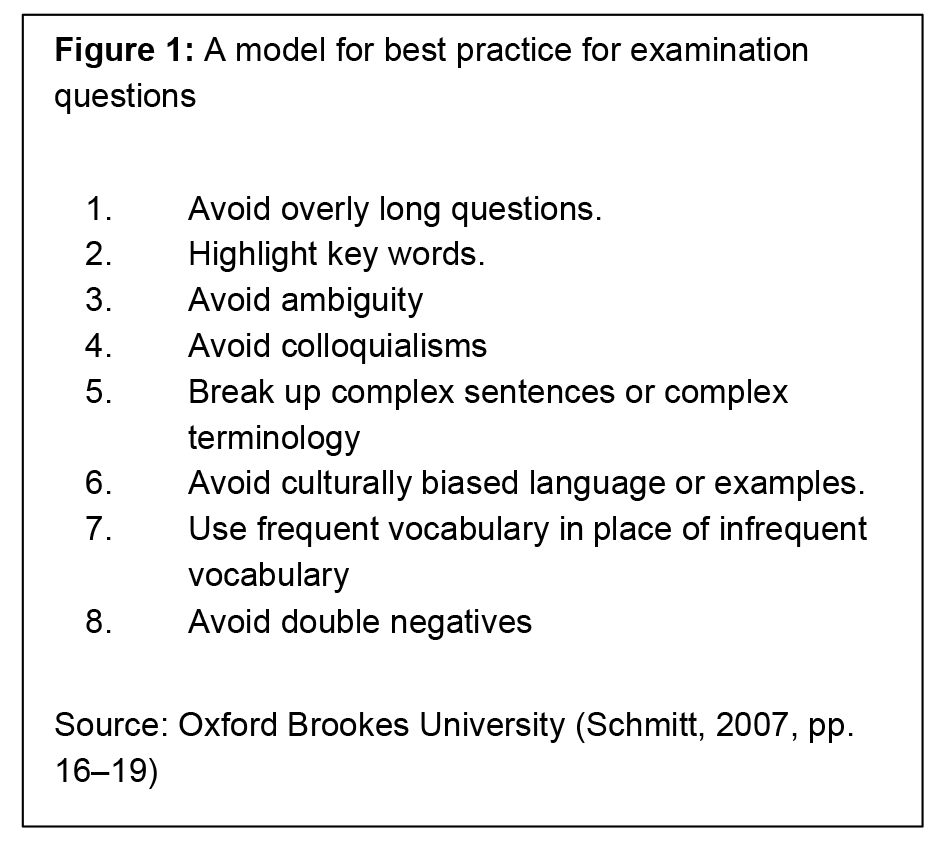

The issues that have emerged can be now summarised under three broad themes in Table 1 below. They suggest a two stage evaluation of firstly, university standards and practices, and secondly students’ own experience.

Table 1: Themes identified from the literature

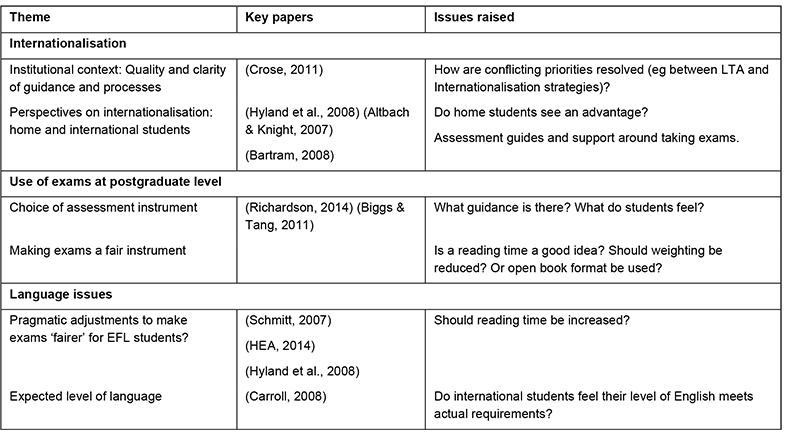

University standards and practices were evaluated using the issues in Table 1 as a tool for interrogating relevant policy documents. The anonymised outcome of the document review process is summarised in Table 2 below; it is assumed that most universities will have documents with equivalent purpose and content. A limitation is the age of some sources; inevitably, the university documents were at different stages in their life cycle: for instance, the published Enhancement-led Institutional Review (ELIR) inspection was in 2010/11, with the next review not completed in time for this review. The UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) is an emerging framework for benchmarking HE teaching practices (HEA, 2011).

As can be seen, the issues identified in the literature review are generally addressed in university documents. Notable is a lack of detailed guidance on internationalisation and EFL issues in exam design, particularly to acknowledge the challenges faced by less fluent EFL students.

Table 2: Summary of findings from review of university documents

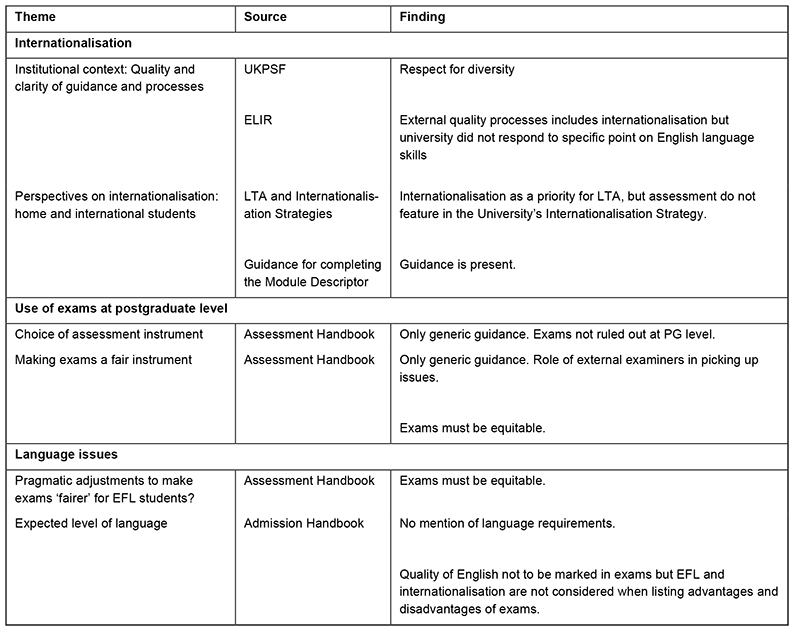

Students in two Computing-related MSc programmes which shared a number of business-oriented modules were surveyed. Ethical issues were addressed through a lightweight gatekeeper-based approach which established that as sensitive personal data was not involved, it was sufficient to use an informed consent form to emphasise that participation was optional and anonymity guaranteed unless the students chose to share details.

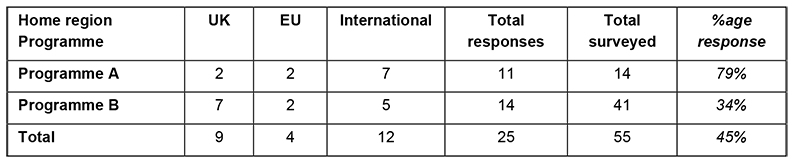

As many students were no longer on campus data collection was through an online survey constructed using the findings from the literature review and the review of university documents. Email requests were sent to 55 students, with 31 responses, 25 of which were complete and could be used for analysis. The overall survey results are summarised below, along with students’ self-reported home region:

Table 3: Survey response summary: response rate by course

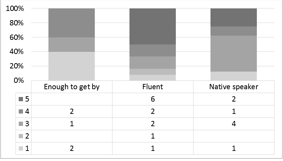

This response rate is acceptable for an optional end of term survey. It is worth noting that that the response rate was significantly higher for Programme A; an obvious explanation is that the author is programme leader so students were more likely to respond. At least one student in Programme B had had no exams – this could also have affected the response rate. Additionally, the nature of survey population may be significant: the number of non-UK students on Programme A was high; they would be expected to be more interested in a survey of this nature (only 14% of students are from the UK, compared to approximately 50% for Programme B). The table also gives an overview of the relation between home country and self-assessed language level, though as language ability is self-assessed, there will be inconsistency: three UK students assessed themselves as fluent rather than native speakers. This may reflect lack of clarity in the question, or it may be that some UK students have an EFL (or ESL – English as a Second Language) background. It is also interesting to see that two international students self-identify as native speakers (they are both from Nigeria). Finally, one student known to the author to be fluent in English categorised herself as ‘enough to get by’. Time constraints did not allow for interviews or focus groups to be used to supplement the survey findings.

At this stage, it is enough to note that the response rate is sufficient to put some reliance on the results within the limitations noted in the introduction.

This section uses the results of the review of literature and university documents to evaluate the results of the survey for implications for the programme and the university generally. It provides the basis for recommendations for change at module, programme and university level.

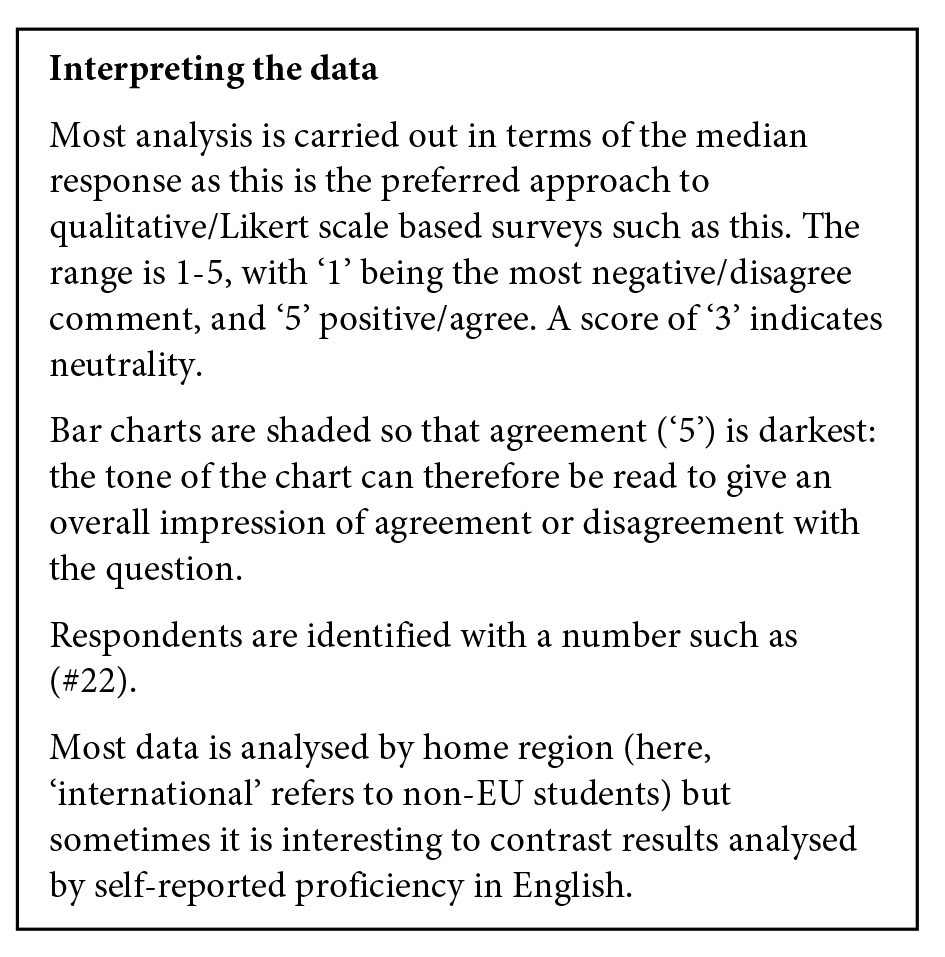

This addresses the university’s approach to internationalisation and diversity, and students’ experiences of it. The survey response indicated that students felt the university respected diversity (Figure 2), with 16 out of 25 (64%) agreeing that their course “has done [well] in respecting the diversity of the students” and half (13/25 overall and 6/12 international students) agreeing that their course reflected the “university's stated policy of internationalising its courses” (Figure 3); only 2/25 disagreed. This therefore gives a positive overall impression, in line with the review of university documents and external quality processes which found an acknowledgement of the importance of internationalisation, and the need to respect diversity.

Figure 2: Q8: [The] course has done [well] in respecting the diversity of the students

Figure 3: Q8: [The] course has done [well] in reflecting the university's stated policy of internationalising its courses

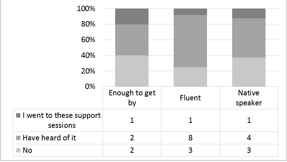

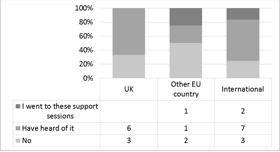

When asked if they were aware of language training and support for EFL students, particularly for exam preparation (Q1) (Figure 4 and Figure 5), only 2/5 ‘enough to get by’ students’ had heard of exam support and preparation sessions run by academic support, and 1/5 actually attended, showing a possible issue with engaging students with poor English.

Figure 4: Q2: Are you aware of language training and support for EFL students, particularly for exam preparation? (by language ability)

Figure 5: Q2: Are you aware of language training and support for EFL students, particularly for exam preparation? (by country)

General questions (not illustrated) established that the level of language was seen as enough to understand the teaching material and lectures (median ‘5’ for all categories). Students also reported that they were able to reflect their knowledge in coursework with medians of ‘4’ for both non-UK and non-native English speakers. Although exam preparation was identified as having room for improvement, no significant language based issue is apparent. Specific areas here are more teaching in academic writing (#9, Nigeria) and also a need for support for spoken English (#10, Pakistan), though there was also a point raised by a UK student (#14) on the clarity of the learning material. “Make sure that the English used by staff is fit for purpose.” There was support for requiring the use of English from international students: “As advertised by university... the medium of instruction for courses are English… and students are expected to meet some minimum standards.” (#10, Pakistani), though some accept that, native English speakers will have an inherent advantage in an English medium course (#19, Uruguay)

It is possible to explore the impact of internationalisation on the exam process in more detail. The students had no strong feeling that the exam language puts home students at an advantage (Figure 6); though a significant minority of fluent and native speakers strongly disagreed, others did agree there was an issue.

Figure 6: Q3: The exams put home students at an advantage because of the language used

Overall, exam topics themselves were not generally felt to be an issue (Figure 7), with medians at ‘1’ or, ‘2’ (disagree) but it is clear that a minority of non-UK students do see a problem: 5/16 EU and international students agreed to some extent that the exam topics did put home students at an advantage.

Figure 7: Q3: The exams put home students at an advantage through choice of exam topics (by home country)

The lack of engagement with poor English speakers and the feeling by some students at least that language and topics give home students an advantage is a concern as the teaching and assessment approach is built on the assumption that students are fluent (or at least very competent) English users, and enforces the point made in the literature about the lack of detailed support at institutional level (Daniels, 2013; Thomas, 2002) – for instance, document review had found no mechanism to review language or exam topics for compatibility with the internationalisation strategy, this is in addition to weaknesses found in addressing language issues specifically.

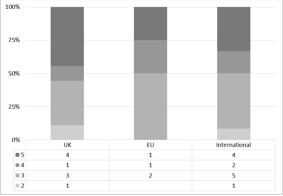

Here, the focus is on alternatives to exams, examining international and language issues specifically. Only one specific alternative was given in the survey: assessing on attendance and participation at 10% of the course marks. Views were mixed – the majority of fluent and native speakers were neutral on the concept (median ‘3’), with a strong minority (3 students in each) who strongly disagreed (‘1’). The reason for this would need investigated: it may be work and family commitments: even with recognition that tutorial attendance is “critical” (#22), “there are many people who work and have another issues” (#21). Another explanation may be wariness of being judged on ‘engagement’ by tutors: one student saw this option as “laziness on teacher’s part” (#17, Scottish). This is consistent with the broad literature (Richardson, 2014) where assessment by participation was not a popular option.

Figure 8: Q7: Idea – mark students for their attendance and participation in tutorials

Students were asked for their own ideas: a number of variations on coursework (such as more, briefer, assessment, case studies and peer marking) appeared as suggested alternatives. Interestingly, one student requested “More exams” (#9, Nigerian) – along with the earlier student comments, this may show that there is a desire by some EFL students to demonstrate that they can succeed in a English language academic environment (Carter, 2012).

The findings emphasise the importance of ensuring that exams are seen as being fair, and that the university has effective processes in place for ensuring that exams are set and marked appropriately (Payne & Brown, 2011). Students’ responses showed support for a range of assessment instruments, including exams (Crose, 2011). These ideas need to be judged in line with resources and broader LTA approach.

Examinations are not considered an optimal assessment route for EFL students as they put too much strain on surface skills. The preference in the literature is for written essay style assessments as they make it easier to overcome language barriers (Crose, 2011). However, there is also an acknowledgment that plagiarism is a risk with courseworks (Daniels, 2013). Exams remain a significant assessment method with a body of good practice material available to mitigate the issues (Schmitt, 2007).

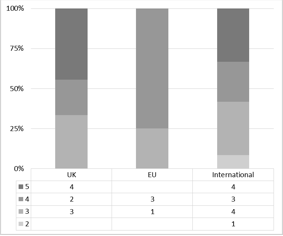

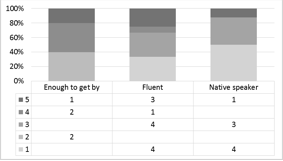

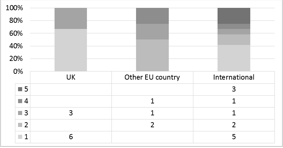

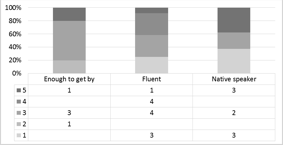

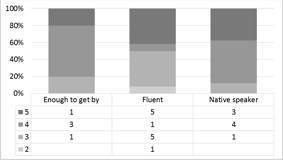

Superficially, students of all language abilities seem to be happy that the exams allowed them to reflect their knowledge, with medians of ‘4’ (Figure 9). However, analysis by region of origin (Figure 10) shows a different story: although UK and international students are satisfied with the process, the EU students disagree (median ‘2’). This may reflect educational backgrounds, and the acceptance of an exam culture by international students (HEA, 2014) – or simply the small size of the sample.

Figure 9: Q1: I was able to reflect my knowledge of the subject area in the exams (by language ability)

Figure 10: Q1: I was able to reflect my knowledge of the subject area in the exams (by country)

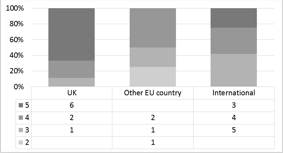

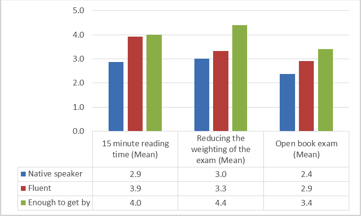

Students were asked for feedback on options to improve the exam experience: three specific ideas were given and a rating (1-5) requested. The results are reviewed in relation to reported English skills in Figure 11 below and are discussed in descending order of popularity.

Figure 11: Q4: Ideas for improving the exam experience (by language ability)

Although the option of word processed answers was not raised explicitly, one student (#10, Pakistani) did comment that they were unpractised in hand writing. However, discussion with other students in class with below average English had established that they do not see that having the option of a keyboard would help them (as it gives an advantage to students who are familiar with the UK English keyboard layout). This could be investigated further in the light of the work of Mogey’s project reported in the literature.

On the issue of the impact of quality of English on exam marks (Figure 12), fluent English students saw this as more of an issue (median 4 = ‘Agree’) compared to poor and native speakers (median ‘3’). The fact that score is 3 or greater across the board indicates that quality of English is felt to affect marks to some extent, which is one of the concerns raised in the literature (Schmitt, 2007).

Figure 12: Q1: I feel that the quality of English in my exam answers will affect the marks I receive

The data from the survey and the review of documents has shown that there is no significant perceived issue with exams, even in a course with a large number of international students. It also seems that students do generally perceive themselves as being in an internationalised environment that is aware of diversity showing the impact of the internationalisation strategy, despite weaknesses and inconsistencies identified in some documents.

The findings do indicate that the university’s assessment manual should address writing exams for EFL students directly, rather than simply referring to Schmitt (2007). More emphasis should be given to the quality of recruited students’ English, so international students can feel more engaged in tutorial activities and teaching resource can be focussed on the subject matter, not language support. Finally, more could be done centrally to encourage students with marginal academic English to access the support available to them.

At module level, findings from the survey indicate that the following changes should improve students’ perceptions:

Students should be given the chance to prepare for exams: question types and the chance to practice exam answers. Students with weaker English should be routinely encouraged to take advantage of support.

These changes can be recommended by programme leaders to module leaders in their course. They generally reflect existing known good practice.

Further work to explore or validate the findings could include a follow-up survey on the same programmes in the future to see if the findings hold for a different cohort. The survey could confront plagiarism directly (eg how useful students feel exams are in detecting or deterring plagiaristic students). It could also address the question of preferences for keyboard input.

The contrast in responses when analysed by home country or English proficiency suggest that LTA practice in this context should be clear whether and when language or culture are the main barrier to students. Consistent with (Bartram, 2008), the survey responses have focussed on academic needs. A related area of further work would be to separate the issues around examining postgraduate students from those of examining international students, but for instance surveying undergraduates.

A significant area that the research could not explore were the importance of home students appreciating the opportunities provided to them by internationalisation – in particular, their perspectives of any adjustments made to assessments by examination (Hyland et al., 2008) and the importance of recognition of socio-cultural needs and peer support for international students (Crose, 2011). It would also be interesting to investigate whether maturity and past work experience of the students is a significant factor in success for international students and to review past coursework and exam marks to see if there is a noticeable difference in spreads and overall marks as has been claimed (Galloway, 2007, p. 6).

The aim of this project was to evaluate postgraduate international students’ perceptions of exams. It did this by identifying three themes in the literature: internationalisation, use of exams at postgraduate level and the significance of the language issue in perceptions of exams and using them as a framework for analysing university policy documents and then the students’ own reported perceptions. The results are enough to test received wisdom and identify broad themes and areas for further work.

More factors than could be addressed in this project emerged from the literature; the survey itself generated more data than could be analysed and evaluated in space available; a tightening of the focus of the questions on a single theme instead of the three chosen would have helped.

Within the limitations noted at the start, it is gratifying that the result is that no need for significant changes to exam assessment emerged, with general support for a diverse, international student body seen in the documentation and the students’ experience.