Ruth Pickford, Leeds Beckett University, UK

The term ‘student engagement’ is contested internationally, used variously to refer to students’ engagement in their studies, in quality enhancement and quality assurance, and increasingly used interchangeably with notions of student partnership. Many student engagement texts do not contain explicit definitions, making the assumption that their understanding is shared, and resulting in the term being a buzzword (Vuori, 2014).

Higher education institutions (HEIs) need to clarify what student engagement means if they are to engage with their students to enhance each student’s experience and to underpin organisational learning. This paper sets out to clarify student engagement in the context of a diverse HE population, to explore what institutions in reality can (and cannot) do to impact positively on student engagement and to provide a high-level pragmatic framework to enable higher education institutions and course teams to design holistic, targeted engagement strategies.

One of the reasons for the confusion surrounding student engagement is a lack of clarity about the purpose of student engagement; engagement with what and to what end? A range of perspectives relating to higher education goals, expectations and student motivations can be identified in the literature. Student motivations will necessarily determine the nature of each student’s engagement.

One body of research focuses on the role of higher education in developing a learner’s sense of identity, mutuality, purpose, self-efficacy and confidence and improvement of the quality of their own life (Palmer, Zajonc, Scribner & Nepo, 2010; Levine & Dean, 2012). These perspectives generally highlight the importance of graduates being able to establish sustainable networks and to work with others, to be able to form working relationships and work effectively in symbiotic teams; to be able to lead in complex, socially diverse contexts having highly developed intrapersonal and interpersonal skills (Kiziltepe, 2010), and to be able to make decisions based on personal values and personal integrity (Haigh & Clifford, 2011).

Others’ perspectives, including that of Hansen (2011), recognise the advantages of graduates being responsible, autonomous learners capable of lifelong learning, who possess sophisticated oral, written and digital literacies that enable them to effectively communicate, argue, persuade and work reciprocally. It is suggested that graduates should have developed academic, cognitive, intellectual, analytic and problem solving skills (Sullivan, 2011; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005) and will also have developed the knowledge and capability to move into further study at higher levels (Pryor et al., 2012).

Furthermore, Henderson-King and Smith (2006), and Saltmarsh and Hartley (2012) highlight the requirement for graduates to be empowered to be active citizens playing a role in public and professional engagement, to be able to fulfil family expectations, obligations and aspirations (Bui, 2002), to have the necessary skills and profile to enter into desirable careers and to be qualified for well-paid, competitive graduate positions (McArthur, 2011; Kennett, Reed, & Lam, 2011).

Views relating to higher education goals and motivations are diverse. As this and other literature suggests, the purpose of higher education in any individual context will necessarily determine the expectations relating to the nature of student engagement. It is therefore understandable, given the range of goals that higher education is expected to meet, that there is a lack of agreement around the definition of student engagement. Many initiatives focus on only one dimension and even then often tenuously. “[Engagement] studies tend to measure that which is measurable, leading to a diversity of unstated proxies for engagement recurring in the literature and a wide range of exactly what is being engaged with under the mantle of student engagement” (Trowler, 2010, p. 17). Student engagement, if it is to meet the requirements of all those invested in higher education, has many purposes but individual HEIs may prioritise particular aspects of student engagement. A further complication is that whilst HEIs need to be cognizant of the goals of all higher education stakeholders, student engagement requires individual student buy-in and one recent study (Chan, Brown, & Ludlow, 2014) identified misalignment between the perspectives of many students and those of HEIs.

A vast array of engagement principles, taxonomies, scales, initiatives, case studies, tools and surveys has emerged across the sector. As HEIs, driven in some cases by national policies, introduce broad-brush ‘engagement’ initiatives ranging from introduction of attendance policies, to badging and verification of expected extra-curricular and super-curricular activities, engagement is progressively defined on the institution’s terms rather than the student’s. The conflation of student engagement with the meeting of institutional expectations such as use of the institution’s virtual learning environment (VLE) or participation in group work, has led to ‘student engagement’ becoming a politicised term, increasingly vested with notions of power, compliance and control over students hemmed in by an HE system that continually looks to history and is ill-suited to the needs of individual students. Many HEI websites routinely publish institutional engagement strategies, some promoting the institutional student representative system, others the mechanisms in place to support student feedback or particular student partnership schemes. Definitions of student engagement are often written from an institutional rather than a student perspective with little emphasis given to student choice over the nature or extent of their own engagement. The emerging narrative that student engagement should be owned and defined by the institution needs to be challenged. Engagement should not primarily be institutionally-owned and defined. As each student will wish to engage in an individual way depending upon their goals and motivations engagement should be regarded as a multi-dimensional, personal, student-owned construct.

In order to successfully engage with the range of students entering higher education it is necessary to appreciate different students’ perspectives, their motivations for coming to university and the different ways that students choose to engage.

It is tempting for HEIs to consider students as a homogenous body driven, depending on the perspective of the observer, by desire for enhanced employability, or intellectual hunger for their discipline, or personal development. Worse still, possibly, are attempts to generalise about students from different backgrounds. In her ‘Student Engagement Literature Review’, Trowler (2010) observes that “much of the literature demonstrated reductionist or essentialised views of ‘the student’, with assumptions about sameness among ‘Y Generation’ students or ethnic minority students or older students as distinct from some essentialised view of ‘the traditional student’” (p. 49). However, student contexts and student perspectives vary. Every student approaches his/her higher education in a uniquely personal way, driven by a complex combination of experiences, preferences, limitations and ambitions. It is to be expected that students driven by different goals and motivations will have varying relationships with their HEI and choose to engage in diverse ways with their course, and HEIs need to recognise this and respond to this.

It is valuable to appreciate the diversity of higher education motivations in order to consider how students with various drivers, expectations and goals might choose to engage with their HEI, and what the implications might be for practice. Much of the current discourse suggests that the student body is looking to work in partnership with higher education institutions. However, Coates (2007) proposed a typology of student engagement styles which identified transient states of intense, independent, collaborative and passive engagement. This paper recognises that whilst some students may wish to invest more in their university experience and be involved in opportunities presented to work in partnership to enhance their and other students’ experiences, there are many more who simply wish to achieve a qualification that will enhance their employment prospects, or to focus on mastering their discipline, or even to enjoy the social aspects of the university experience.

Whilst student engagement preferences will likely vary across institutions and across disciplines, any institution that fails to recognise and accommodate the continuum of individual engagement preferences risks disengagement of their students.

Although individual students are ultimately the agents in their own engagement, institutions have a role in fostering engagement (Harper & Quaye, 2009). Institutions must provide the conditions that promote engagement and provide opportunities and enable diverse populations of students to be engaged, not least because, as Krause (2005) suggests, some students do not appreciate the benefits of engaging with people, activities or opportunities in the learning community.

The responsibility of an HEI is to foster engagement through ensuring opportunities are available to all students, whilst acknowledging that the responsibility for engagement lies with the student. The heterogeneity of the student body requires institutions to meet students’ needs to engage in different ways, through providing a range of opportunities. Institutions need to adopt pragmatic, targeted approaches to deploying resources to promote engagement and to provide each student with the appropriate opportunities to make engagement for that student possible.

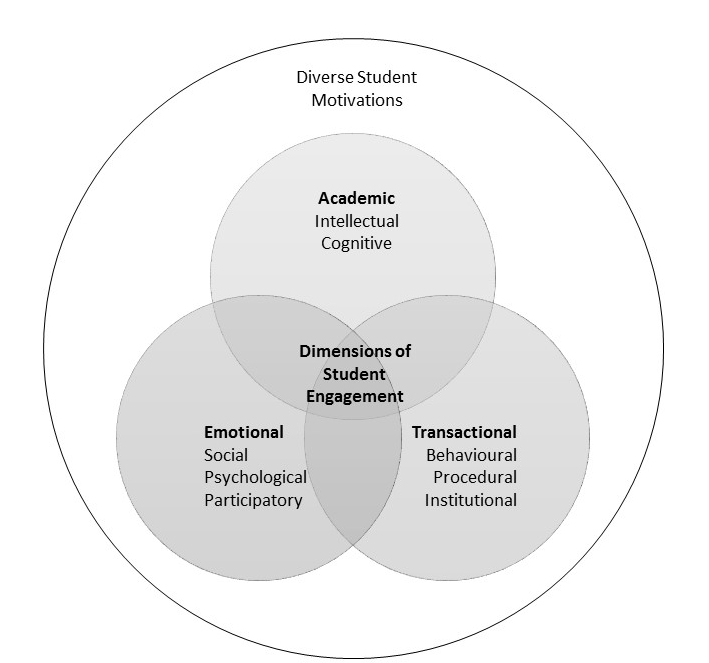

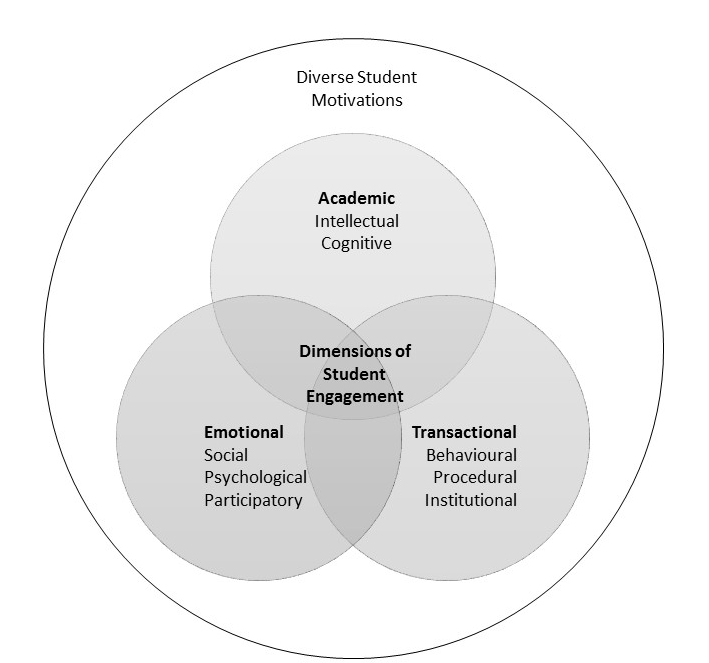

The literature abounds with attempts to describe and usefully classify different forms of student engagement and whilst simplifications are best treated cautiously there is value in modelling the complex reality in a way that supports development of engagement strategies that provide opportunities for all students to engage. Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris (2004), in Trowler (2010), helpfully identify three dimensions to student engagement: behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement. Broadly grouping the spectrum of engagement modes in this way as behavioural/transactional, emotional/social and cognitive/academic dimensions is useful (figure 1). However, in doing so, care must be taken not to lose sight of the individualistic nature of each student’s engagement and to recognise that individuals may choose to engage in one or more of these ways. Trowler proposes that students can engage positively along one or more dimensions while engaging negatively along others. A student may engage behaviourally if they regard their relationship with the HEI in transactional terms, possibly as a route to a professional qualification. In this extreme case the student may regard engagement as a noun as in, ‘an engagement at 10 a.m. with tutor’, and abide strictly by the terms of the agreed arrangement. Another student, engaging academically with the concepts, the research and the challenge of their discipline may choose not to form close attachments to others on their programme including tutors, but nevertheless achieve high grades. It is important to accept each student’s response as a valid, personal choice and to support students who make a rational decision not to engage with every aspect of ‘the student experience’. Whilst many students enter higher education with a personal combination of goals that lead them to engage emotionally, academically and transactionally, others do not wish to engage in all these ways. Students do not need to be engaged in all aspects or functioning in all areas to be successful in their own terms.

Figure 1: A broad conceptualisation of dimensions of student engagement

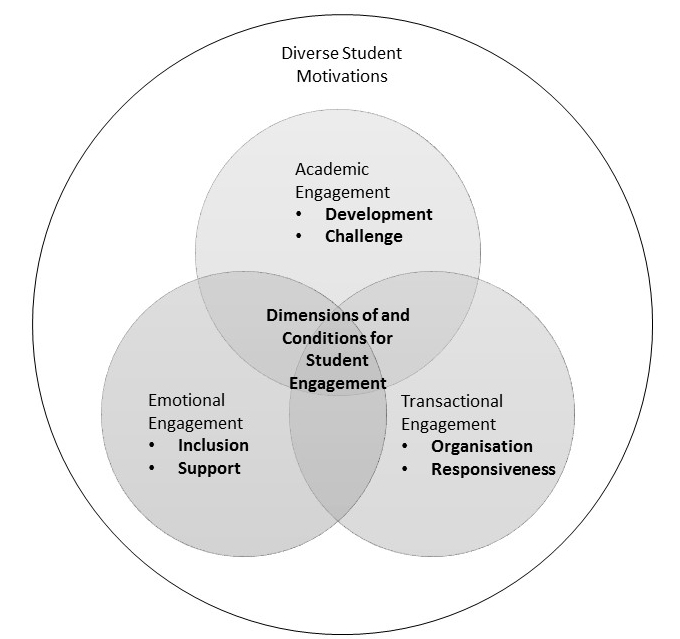

Evidence suggests that certain conditions can foster various modes of student engagement, and that the absence of these conditions can lead to non-engagement or disengagement of some students. Some of these conditions, for example a student’s extra-curricular activities or place of domicile, are most often outside the HEI’s direct locus of control. However, the literature clearly identifies six conditions, within the influence of HEIs, which are linked to general increases in the levels of student engagement. These are opportunities for students to engage through an inclusive sense of belonging or membership to a learning community (Thomas, 2012); development of supportive relationships with teachers and peers (Kandiko & Mawer, 2013; Chickering & Gamson, 1987); development of academic skills that enable engagement in higher learning (Christie, Barron, & D’annunzio-Green, 2013); appropriate intellectual challenge (National Survey of Students Engagement [NSSE] 2002); relevant, well-structured, well-organised programmes (Biggs, 1996; Gibbs, 2010; Race & Pickford, 2007; Fredricks et al., 2004); and agreed expectations, conditions and opportunities for learning (Higher Education Academy [HEA] & National Union of Students [NUS], 2011).These conditions can be summarised as inclusion, support, development, challenge, organisation and responsiveness. It is not suggested that any individual student requires that all these conditions be present; rather that the presence of this set of conditions provides opportunities for all students to engage.

It is useful to consider the relationship between the different dimensions of student engagement (which I have broadly identified as academic, emotional and transactional) and the conditions that are known to generally support different types of student engagement (inclusion, support, development, challenge, organisation and responsiveness). This mapping forms the basis of a multi-dimensional student engagement framework that provides conditions to enable each student to engage in a way that fits with his or her goals and motivations (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Alignment of student engagement dimensions (academic, emotional and transactional) and conditions (development and challenge, inclusion and support, organisation and responsiveness)

It is evident from the range of engagement initiatives and case studies that there is little consensus as to how HEIs are best able to employ strategies to positively impact on engagement of all their students. There is often a disconnect between sets of aspirational high-level principles and the practicalities of increasing engagement of a diverse body of students driven by different goals and motivations. This can translate into top-down directives relating to behavioural expectations that take no account of individual student contexts. Additionally, student engagement initiatives often do not align with organisational structures or processes and are consequently implemented as enhancement add-ons to the students’ experience, rather than being embedded into business-as-usual. Piecemeal engagement initiatives that fall outside a student’s core experience are less likely to be successful, particularly with regard to those students who would benefit most from engagement opportunities.

There is a requirement for a common, manageable framework that can be used both at an institutional level to strategically allocate expensive teaching and support resources, and at a programme level to embed conditions for engagement into the day-to-day operation of the course. Having already established that best practice in engagement is inclusive, encompassing various predispositions to engage academically, transactionally and emotionally, the next step is to consider how positive actions could be embedded into practice to provide the conditions for all students to engage. Interventions should, as far as possible, be embedded into mainstream provision and should proactively seek to engage students and develop their ability to do so (Thomas, 2012).

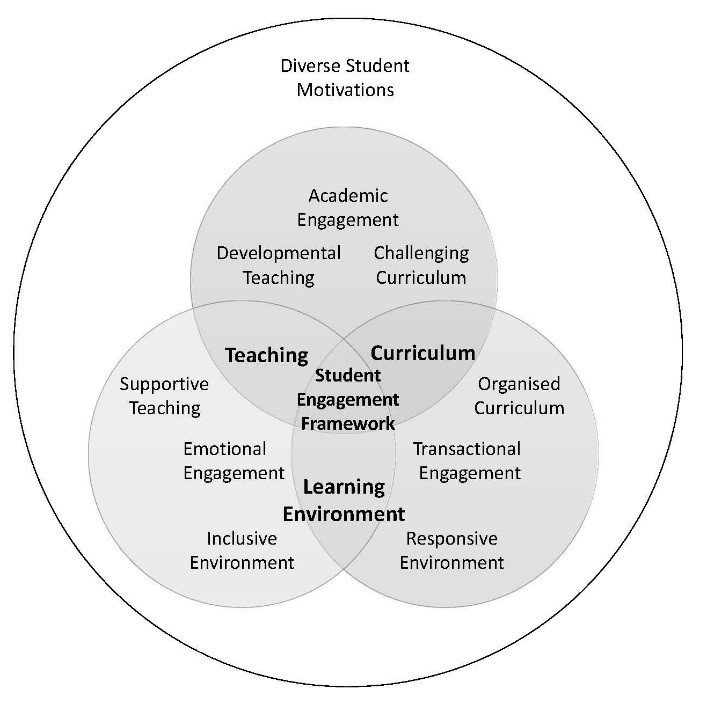

Every HEI controls three aspects of the core student experience which, if designed purposefully, can together impact positively on the engagement of all students. Separately each can provide opportunities for students to engage academically, transactionally and/or emotionally; together they determine the institutional culture of engagement. These three institutional influencers are learning environment (conditions, resources) the curriculum (activities, assessment), and teaching (support, feedback). Proactively engaging with differently motivated students through supportive curriculum design, through adopting particular teaching approaches, and through a well-designed learning environment forms the basis of an embedded approach (figure 3). Pragmatically, all six conditions for engagement can be embedded into the core student experience through the strategic, integrated design of teaching, curriculum and learning environment.

The clear communication of expectations, and explicit and proactive consultation whereby “opportunities are provided for students to express individual opinions, perspectives, experiences, ideas and concerns” (HEA & NUS, 2011) underpins active participation. Structures and processes that support feedback and negotiation and that give individual students a voice in shaping fit-for-purpose provision develop a student’s sense of control over their environment.

Additionally, it is known that demonstrating the value of activities and assignment tasks and relating requirements to students’ previous experiences, to real world and real life contexts and ensuring that what students are expected to engage with is useful, informative and relevant to their interests and future goals, underpins engagement of those students who need to perceive activities as being personally meaningful (Fredricks et al., 2004; Thomas, 2012).

A well-designed curriculum delivered through a well-organised course will scaffold development of graduate attributes through coherent, relevant, and well-structured activities and assessment. A student’s conditions, opportunities and expectations are shaped through their course, and a responsive learning environment encourages students, through supported, ongoing consultation, to provide feedback about their conditions and resources. Together an organised, relevant curriculum and a responsive learning environment provide embedded opportunities for transactional engagement.

A student’s understanding of the nature of independent higher level learning underpins their ability to engage (Christie et al., 2013). Academic achievement is related to active participation and students need to be supported to learn how to learn (Claxton, 2008). Learning is influenced by participation in activities that research has shown is likely to lead to high quality learning. Prompt feedback is known to be effective (Chickering & Gamson, 1987), as is peer modelling, and practicing the skills that help them to learn (Coates, 2005).

Academic challenge is another key factor in academic or intellectual engagement (NSSE, 2002). Creating an intellectual environment that stimulates debate and discovery and provides challenges to be creative and curious, to generate ideas and produce solutions encourages students to invest in their studies and their academic development. The appropriateness and level of challenge is important, as being able to effectively perform an activity that is stretching plays a role in development of self-efficacy (Bandura & Schunk, 1981).

Teaching approaches that focus on developing self-regulated learners with the skills needed to be able to effectively learn at a higher level, for example through using regular formative feedback, peer and self-assessment, can powerfully complement courses that present students with appropriate intellectual challenge through considered task and assignment design. A co-ordinated approach to embedded higher skills development and higher levels of academic challenge provides a framework for intellectual engagement.

On entering higher education, students can encounter alien language and procedures, feelings of isolation and a lack of sense of positive identity, particularly for those students from underrepresented groups, in relation to their course and to higher education. Findings indicate that a significant minority of students consider withdrawal and that “at the heart of successful retention and success is a strong sense of belonging in HE for all students” (Thomas, 2012, p. 6). A sense of community has been linked to increases in engagement (Zhao & Kuh, 2004), particularly a sense of belonging to a cohort or membership of a course.

Cooperation among students, and between students and staff are known to be linked to positive outcomes (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). “Relationships between staff and students and peers promote and enable student engagement” (Thomas, 2012, p. 8). In the case of relationships with teachers, contact with staff has been shown to have a positive impact on student levels of engagement (Pike, Kuh, & McCormick, 2010; Yorke & Thomas, 2003; Leese, 2010), especially when it responds to individual student needs and when it takes place outside the classroom (Chickering & Reisser, 1993). Likewise, interactions with diverse peers have also been shown to have positive personal and social outcomes (Villalpando, 2002; Chang, Denson, Saenz, & Misa, 2006), and working effectively with others and collaborative learning can be a powerful facilitator of engagement (Wentzel, 2009).

A learning environment that prioritises cultivating an inclusive sense of belonging to a learning community accompanied by supportive teaching approaches that scaffold relationships between each student and their teachers and peers, fostering social connections and providing, for example, opportunities for small group discussion, collaborative and active learning, and interactive activities that help to reduce barriers created by large group anonymity can provide the embedded opportunities required for emotional engagement. Mortiboys (2006) argues that it is critical to recognise the power of emotions in learning by teaching with emotional intelligence; “Students who engage emotionally would experience affective reactions such as interest, enjoyment or a sense of belonging” (Trowler, 2010, p. 5).

Figure 3: An embedded multi-dimensional student engagement framework

As HEIs compete in an increasingly marketised environment a high level of student engagement has become not only an ethical obligation, but also a reputational requirement, and a financial imperative. There is evidence that high student engagement leads to high retention rates (National Audit Office [NAO], 2007), high achievement and learning gains (Gibbs, 2010), high satisfaction (Coates, 2008), and improved employability (Senior, Reddy, & Senior, 2014). However, engagement can only be achieved if we provide opportunities for all students to engage in ways that align with their individual contexts. In the UK, the widening participation mission of some universities makes it incumbent upon the institution to ensure all students have an equal chance of success, and the financial penalties attached to drop-out, together with the use of metrics such as the UK NSS and DLHE scores to rank institutions in league tables has meant that attention to, and the profile of, student engagement has increased. In order to ascertain how their students engage, many institutions are using engagement surveys based on the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) such as the UK Engagement Survey. Whilst these surveys move the focus towards student behaviours they are still anchored in an institutional paradigm of what good engagement looks like. Levels of student access, progression and achievement rates, and indicators of student dissatisfaction with hygiene factors such as feedback and course organisation are all directly related to the range of emotional, intellectual and transactional student engagement opportunities that an institution provides. Rather than focusing on, and reacting to, each of these in a piecemeal way, institutions would do well to develop a culture of student engagement through an embedded, holistic framework.

In order to engage with all students, individual student goals whether intellectual, personal, professional or more likely some combination, need to be embraced in a cost-effective, manageable framework. The objective should be to provide opportunities for engagement. Compelling all students to engage in prescribed ways will undoubtedly lead to negative consequences for those students motivated to engage in different ways.

The high level student engagement framework proposed in this paper considers the broad range of expectations and goals that higher education is expected to meet, and how the various motivations of students and other HE stakeholders relate to the student engagement agenda. A student engagement framework identifying the relationships between goals, engagement and practice is useful in considering how individual, course level and institutional practices may be developed to optimise engagement of all students. It can be used as the basis for development of holistic student engagement strategies both at institutional and course level and to underpin approaches to student transition and induction, personal tutoring, and development of student partnership strategies. Whilst institutional missions and course contexts vary, the conditions of engagement have broad applicability. In the same way, references to ‘curriculum’, ‘learning environment’ and ‘teaching’ may need to be tailored to fit local contexts but nevertheless identify the three broad institutional influencers of student engagement.

Student engagement is a goal in itself and this paper has highlighted the need to recognise, accommodate and provide opportunities for engagement to students with specific motivations and goals. Nonetheless, a sustainable, fit-for-purpose 21st century higher education system requires HEIs to engage with students for the dual purposes of enhancing each student’s experience, and organisational learning to improve the HEI’s engagement practices. The strategic leadership of student engagement should primarily involve identification and allocation of teaching, curriculum and learning resources to provide opportunities for all students to engage emotionally, transactionally and/or academically.

At a strategic level, a holistic engagement vision should form a central part of corporate planning. This needs to be implemented at every organisational level, through a clear vision translated into institutional key performance indicators supported by aligned engagement-focused infrastructure, recognition and reward systems. It is suggested that the framework outlined in this paper can usefully support development of student engagement strategies that meet the needs of students and institutions in the emerging HE context.