Willie McGuire, Rille Raaper, School of Education, University of Glasgow, UK

While it should be noted that there is a comparative paucity of research into this topic when indexed against formative assessment, assessment moderation in this study, guided by Bloxham (2009), is understood as a process for assuring that marking criteria are applied consistently and that assessment outcomes are valid, fair and reliable. The main purpose of moderation could be seen, therefore, in relation to “equitable, fair and valid” assessment processes; processes that align with set criteria, standards and learning outcomes (Adie, Lloyd, & Beutel, 2013, p. 968). While moderation could be seen in relation to fairness and standards, the practice context of moderation is still surrounded by several concerns. For example, Lawson and Yorke (2009) argue that, at the practice level, moderation is often understood in different and contradictory ways: in some cases as double marking and others as a more elastic, holistic process that incorporates both assessment design and collegiality. This would imply that some approach assessment and moderation simply as the culmination of learning and teaching processes (James, 2003), reflecting “idiosyncratic and sporadic processes informed by luminal understanding” (Adie et al., 2013, p.968), while others perceive it through a much wider lens. To add to the complexity, Lawson and Yorke (2009) explain that moderation processes are not generally recognised in academic workload allocations making assessors feel highly pressurised, and Bloxham (2009) draws further attention to the fact that the moderation part of assessment has been very little studied in assessment literature reinforcing the point made at the opening of this paragraph.

In this complex and rather problematic context of assessment moderation, there tends to be a clear shift towards the standardisation of assessment and moderation practices. It remains unclear if this shift is a response to concerns characterising assessment moderation as mentioned above or perhaps it is caused by wider structural changes such as the expansion and internationalisation of higher education in the UK. Stowell (2004 ) tends to see inevitable tension between widening participation and the focus on academic standards. Furthermore, Price (2005) avers that growing student numbers in higher education also mean that teams of academic staff rather than individuals need to apply and agree on standards, which might also require a more centralised and institutionalised approach to moderation.

While taking into account the concerns and complexities highlighted in recent assessment literature, this paper introduces the key findings of a small-scale research project carried out within the School of Education of the University of Glasgow. This qualitatively driven mixed methods study explores the, essentially, polymorphic nature of assessment moderation practices within the School of Education and, specifically, counterpoints the twin perspectives of course leaders’ and markers’ experiences of moderation; it was also underpinned by the constructivist paradigm of assessors being actively engaged in constructing their meanings, making sense of new knowledge and integrating it with previously held concepts and information (Elwood & Klenowski, 2002). Furthermore, this research project was approved by the College of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee. The research participants were aware of their voluntary participation and confidentiality and their consent was gained before data collection.

Despite considerable differences both paradigmatic and methodological in research projects, it is widely acknowledged by scholars across disciplines that research questions drive methodological decisions (Mason, 2006; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2009). As researchers, we tend to engage with inquiry when we are uncertain about something, aiming to produce data relevant to that uncertainty (Sechrest & Sidani, 1995).This research project started with a literature search that helped to clarify the complex context of assessment moderation and to develop research questions from which emerged a contingent methodology. The project focused on the following questions:

1. How is assessment moderation experienced by course leaders (CL) and markers (M)?

2. What are the strengths and weakness of moderation practices as experienced by CL and M?

3. How could assessment moderation be improved from the perspectives of CL and M?

As evident above, the research questions posed are underpinned by “qualitative thinking” (Mason, 2006, p. 10). Mason describes qualitative research as an inquiry that is interested in the dynamics of social processes and contexts, and in so called ‘how’ questions. However, Mason (2006, p. 9) also highlights the benefits of mixing qualitative and quantitative methods, which would allow scholars “to enhance and extend the logic of qualitative explanation”. Like Mason (2006), and Sechrest and Sidani (1995), we recognise the value of methodological pluralism. We believe that quantitative research with its focus on wider patterns, commonalities and averages (Mason, 2006) can prepare the ground for qualitative research through such processes as the selection of people to be interviewed and the preparation of interview questions (Bryman, 2004). In this study, quantitative methods facilitate qualitative research. In order to overcome the prevalent paradigmatic schism in mixed methods research – epistemological and ontological conflicts between qualitative and quantitative methods – we ground the study in a constructivist paradigm, and apply the survey method only to set the context for further qualitative exploration. We, therefore, reject objectivism and believe that social phenomena and their meanings are continuously constructed by social actors (Bryman, 2004).

In order to conduct this qualitatively driven mixed method research, data collection involved two stages: (1) An online questionnaire was distributed to all academic staff in the School of Education via the staff mailing list; (2) Focus groups were carried out with CL and M who completed the initial survey and volunteered to take part of the focus group.

The online questionnaire included a combination of 25 closed and open-ended questions, addressing the assessment moderation experiences of CL and M at three levels:

1. Pre-marking support

2. Post-marking support

3. Ongoing support throughout the marking process, which may (or not) be in addition to 1 and 2 above

As evident below, these categories did not form the basis of data analysis, but were selected to structure the questionnaire and provide some guidance to participants. As relevant literature has demonstrated the complexity around ‘moderation’, we found it important to guide participants in thinking about different forms of moderation practices: particularly in terms of academics’ experience and confidence with various practices. Each question included an option ‘not applicable to my practice’ and a comment box that allowed participants to explain why a certain form of practice had not been included in their practice. This also allowed us to receive rich qualitative data from this survey method. Most importantly, however, the questionnaire ended with an option to volunteer for a follow-up focus group. We would also like to note that 80% of the focus group participants were recruited through the questionnaire method.

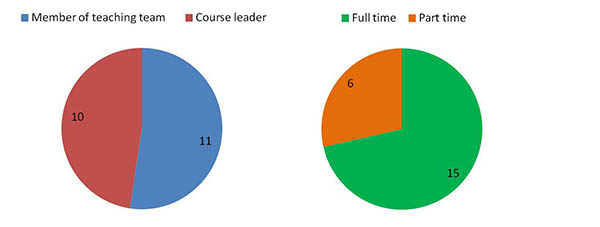

The questionnaire was completed by 21 academics from which 11 participants were members of teaching teams and 10 were course leaders. Additionally, 15 participants were full-time academic staff and 6 were part-time members of staff/associate tutors (Fig. 1). Due to the small sample, quantitative questions were analysed in Excel file and qualitative comments were coded using thematic analysis. Guided by Bryman (2004), thematic analysis included subsequent processes of initial coding of data, incorporating codes into themes and interpretation of the themes in terms of broader analytic arguments.

Figure 1: Profile of the questionnaire respondents

The second stage of data collection involved two focus groups: one with the CL and the other with M. The focus groups involved 14 people in total: 10 course leaders and 4 teaching team members. The aim was to further explore the themes arising from the questionnaire findings. While the survey provided a general ‘feeling’ of the processes and issues related to moderation practices, the focus groups encouraged greater qualitative depth. The questions addressed topics related to participants’ roles in assessment and moderation, their sense of the most and least supportive practices, and university policies and practices on moderation. All focus group data were transcribed and analysed by thematic coding.

The research findings and discussion below are presented based on the overarching key themes emerged from the focus group data. In order to demonstrate the complexity in the field of assessment moderation, we have decided to distinguish the perspectives of the course leaders and markers throughout the analysis.

The questionnaire results revealed the course leaders’ high confidence in practising assessment and moderation. Their perspective on assessment is grounded in professionalism and work experience and tends to confirm recent scholarly work in assessment studies that approaches assessment standards as “a matter of professional trust” (James, 2003, p. 193) and moderation as a “judgement practice” (Wyatt-Smith, Klenowski, & Gunn, 2010, p. 61). While the questionnaire demonstrated course leaders’ high levels of confidence in practising assessment and moderation, the focus groups still highlight the participants’ varied levels of awareness of moderation practices, support mechanisms and institutional regulations. Perhaps one of the clearest differences emerged around the idea of an ultimate arbiter in assessment: course leader, external examiner or course team. Some understood this to be the external examiner while others felt that the role of external examiner was to moderate the process as opposed to the grades. Phrases such as ‘ultimate moderator is the course leader’ (CL1), ‘to me the external examiner is the moderator’ (CL2) and ‘I would argue that in practice it’s whoever takes the role of an ultimate moderator’ (CL3) were common to this focus group and exemplified this lack of clarity.

The broad feeling about the moderation process, however, was that all support mechanisms (pre-marking, post-marking and ongoing support) are important. It was also characteristic of the course leaders to have a broad, but largely unchallenged, agreement that you have to know a course to mark it. Furthermore, their oppositional attitude against further regulation of assessment tended to be also commonly shared. Indeed, an overall resistance against further regulation of assessment and moderation practices tends to demonstrate the course leaders’ understanding of assessment and moderation as being intrinsic to professional practice and judgment, as was argued earlier in this section. Their resistance, however, might be a response to recent policy developments in the field of assessment. As research has indicated, in the UK higher education sector, there is an increasing pressure both within and across institutions to develop common assessment standards (Price & Rust, 1999) in which ‘standards’ are seen to ensure ‘equality’ (Stowell, 2004 , p. 495). Furthermore, as assessment moderation is seen as being a crucial component or subset of educational quality (Smith, 2011), many higher education institutions now have a specific moderation policy or they are moving in that direction (Adie et al., 2013; Lawson & Yorke, 2009).This shift towards standardisation has brought about an increasing use of assessment aids such as criteria, learning outcomes, benchmark statements, specified programmes and standardised feedback on students’ assignments (Price, 2005). It is, therefore, unsurprising that the course leaders tend to be oppositional towards any kind of regulatory expansion. This is especially the case as some scholars argue that the institutional focus on standardisation has been taking place at the expense of developing actual assessment practices (Bloxham, 2009) or creating a coherent philosophy of assessment (Stowell, 2004). Interestingly, one of the course leaders also argued that the School of Education compared to other academic units already has significant advantages in having pedagogically sound assessment procedures and practices that do not require standardised control:

…you know, we have considerable advantages, however critical we are about our own procedures, I suspect that when you look at other schools and colleges where they have no subject based understanding in assessment, it will be much worse. (CL4)

In contrast to the course leaders, the questionnaire results demonstrated markers’ lower comparative confidence in assessment and moderation and confidence levels depending on their work experience and involvement in the teaching of the course assessed, which would suggest that markers tended to be more focused on themselves as assessors rather than on the process of moderation itself, which clearly influenced the views of course leaders. Another key difference tended to emerge in relation to positive emotions: some markers expressed that they enjoyed assessing student work, which was something that did not arise from the course leaders’ focus group:

I actually really enjoy doing it because that you know, it’s my first year last year but I really really enjoyed sitting down […] and that’s quite nice marking on lots of different courses as well. (M1)

…others working with me, you know, when you have your first marker, second marker, that’s been very helpful. I’ve quite enjoyed that, quite liked that. (M2)

In addition to positive experiences, pre-marking procedures were felt to be simultaneously challenging, yet helpful as the individual had to translate private thought into public statement in order to justify the grades awarded. The following example might illustrate the benefits of group discussions in markers’ experience, but also the emotional context it creates for assessment, perhaps reflecting once again the lower confidence that markers have in the moderation processes when counterpointed against course leader perspectives:

The highly structured, having scripts beforehand where you mark them blind and then you come to a meeting […] I find that quite intimidating to start with because when you are thinking you’re around the table and you’re thinking, oh my goodness, someone said an A and I’m thinking, it’s definitely not, you know that’s but again it’s having that courage to be able to justify it really kind of really does make you look at the criteria. (M1)

It could be argued, therefore, that the involvement of emotions and feelings of comfort versus discomfort was highly characteristic of markers, demonstrating their lower confidence in the moderation processes.

The moderation of marking is, essentially, a subtle art in course leaders’ experience. As the research indicated, course leaders have to deal with a number of contextual variables – large numbers of associate tutors, a diverse teaching team from different backgrounds, inexperienced markers and different expectations/expertise of tutors, different standards/ideas – that all have an impact on assessment and moderation practices. Furthermore, while dealing with these variables, they are required to meet the overall aim of moderation, which is to ensure fairness of student assessment (Lawson & Yorke, 2009). In addition to leading a potentially diverse marking team, another facet of the role of the course leader is to manage student expectations, engagement, experience and satisfaction which are often typified in the National Student Survey (NSS) – the UK-wide survey that gathers students’ opinions on the quality of their courses – in which students, perhaps unsurprisingly, regularly exhibit a lack of confidence in the grades awarded. It was felt by the course leaders that this was really the case only when those grades were felt to be lower than the students’ expectations. The opposite of this was felt to be the perceived practice of grade inflation in order to address the concerns of students and the expectations of management. In addition to mediating between markers and students, moderation practices were felt to be influenced by a range of time-related factors such as the time given in which to grade, record and return student scripts as well as the workload allocated to marking and moderation. It is also noted, however, that the allocation of time for marking and moderation might not be the key problem, but rather the overall workload model that shapes academic work. Lawson and Yorke (2009), for example, explain that moderation processes are not generally recognised in academics’ workload allocation models and this causes additional pressures in academics’ experience. Another time-related matter that influences the success of moderation practice is attendance at moderation meetings that cannot be made compulsory because of the competing demands of academic work. The absence, however, of a number of markers tends to leave doubt in the mind of a course leader as that marker’s position on a marking spectrum of severe, lenient or inconsistent had not been tested. It is, therefore, evident that moderation in course leaders’ experience is a complex process that is surrounded by various factors and issues that need to be taken into account and developed.

When speaking about the moderation practices in this complex structural context, course leaders acknowledged that there is a variety of practice across the programmes. This experience tends also to echo an argument by Colbert’s et al. (2012) that even if there is a move towards the development of institutional assessment standards, these standards cannot reflect all of the complex factors shaping assessment practices. Rather, practices tend to vary depending on the course leaders, assessors and courses. For example, the questionnaire results highlighted that some course leaders found that agreeing assessment standards before marking was “extremely helpful” (five participants) or “very helpful” (one participant), while two participants found it “helpful” and the remaining two as something that they had never experienced. Equally, the focus group highlighted the feeling that large courses were experienced as being more problematic and, because of the pressures of marking turnaround, possibly rushed. It became apparent that large and small courses use different moderation practices: in large courses there tends to be more use made of pre-marking with a range of scripts to grade allied to an extended discussion of grades. Conversely, large courses often also included more formal standardisation procedures, especially in relation to the feedback that is provided to students. For example, CL5 reflected on the experience of developing ‘a streamlined feedback sheet’ for a large TESOL course:

I agree, it [moderation] depends on the size of the group, it depends on the size of the marking team, it depends whether they are experienced or they need training. It also depends on how much time is available and workload. (CL5)

While practices clearly differ among the research participants, these did tend to vary around the same theme: the process of how markers engage with one another in order to come to a deliberative, dialogic decision on what constitutes an A or E and to then apply this in their own marking. Although it tends to be often a hidden and tacit process, the most visible method was to issue scripts in advance of a moderation meeting without grades, which would be then decided at the actual moderation meeting. This could be managed in two ways: (1) Monologically, where the course leader scans the students scripts to source exemplars of A-E grades and then issues these in the hope that the marking team will agree; (2) Dialogically, where the course leader samples student scripts and then issues a selection of these to the marking team who then assign grades to those scripts. Crucially, it is via the deliberative, dialogic process of talking, arguing, debating and justifying that final grades for the selected scripts are confirmed. Respondents seemed to agree that the principle of dialogic openness contributed to the moderation process. An example is provided by the CL7:

...we would meet and each brings in a sample across the range and I read (someone’s), and (someone) reads mine, and then I read somebody else’s, and we sit, and we drink coffee, and if we are lucky, we have some cake, and we’ll talk about it. There’s no detailed water tight definitive way of giving people guidance on how to do that provided that they have some kind of expertise and they know the field. (CL7)

Conversely, double blind marking, as a form of post-marking moderation, was universally unpopular among the course leaders for a variety of reasons, both pragmatic and ideological: it is time-consuming and its veracity is also questionable and may even lead to a reductio ad absurdum, creating the necessity for a third marker to intervene where there is discordance in the award of the first two grades. This also has the effect of questioning whether or not true double blind marking is even possible. Indeed, some respondents noted that a variant of this is where the first marker’s grades and comments are passed to the second marker as a way of obviating the issue of discordance, although this also mitigates against the purpose of true double blind marking. The issue of deprofessionalisation was also raised in relation to a perceived micromanagement of marking processes. In summary, assessment moderation was constructed by the course leaders as: (1) Professional practice that requires knowledge and experience; (2) Subjective practice, under which moderation is subjective and flawed; (3) Collegial practice, within which monologic approaches were felt to be less supportive than dialogic structures. Effective marking support was, therefore, best typified as co-constructed moderation.

It could be argued, therefore, that moderation practice can take a number of different forms in course leaders’ experience just as Bloxham (2009) argues that assessors often rely on locally constructed and tacit standards when making their assessment decisions. This implies that they refer to their tacit knowledge – personal knowledge of students, of the curriculum and teaching contexts but also of their personal ‘in-the-head standards’ – when exercising judgment (Colbert, Wyatt-Smith, & Klenowski, 2012, p. 389). Furthermore, assessors may rely on their departmental and/or disciplinary communities when developing or implementing their practices (Price, 2005). Overall, the course leaders’ focus on professionalism, subjectivity and collegiality in assessment and moderation practices tends to reflect and promote the concept of ‘social moderation’ that has been significantly emphasised in recent assessment studies. Social moderation relies on the professionalism of teachers and promotes assessment practices that are locally generated in order to support learning, reporting and accountability processes (Colbert et al., 2012). It starts with collegial task design and discussions on quality and standards necessary for the performance (Colbert et al., 2012). This means that assessment design should be a collaborative process (Lawson & Yorke, 2009) within which assessment moderation becomes part of initial course design (Smith, 2011). From this perspective, assessment becomes co-constructed in communities of practice, and also standards become socially constructed, contested, relative and provisional (Orr, 2007). This understanding of assessment and moderation being (ideally) a social practice tends to be common to the course leaders.

The main contextual issues that were experienced by markers as having an impact on assessment moderation were related to teaching team diversity, inexperienced university markers and new markers. For example, some of the interviewees reflected on their own experiences of marking scripts for courses on which they had not taught, the significant effort it required from these markers and the challenges it presented. Furthermore, marking in an area you have not taught does not only take extra time, it generates anxiety and makes an assessor feel less expert in their work as was highlighted in the previous section. A vivid example is provided by M4:

Does that cause anxiety? Yes, in me absolutely. When I see that and I don’t know, yes I know it’s Education, yes I know what good learning is, I know about interdisciplinary blablabla but I’m not right up with all the key theories, I’ve not read all these books. I’m not teaching on that course, I kind of very general level awareness but I’m not an expert. (M4)

Therefore, the lack of core staff was felt to be a key factor influencing moderation practices, as well as markers who were not involved in teaching the course (mainly associate tutors). Other influencing factors were related to the similar themes raised by the course leaders: student satisfaction, markers’ ‘reputations’, time and workload allocation, time spent on problematic scripts and support given by the course/programme leader. The markers’ experience of course/programme leader’s approachability, for example, was assessed as being ‘helpful’, ‘very helpful’ or ‘extremely helpful’ by all markers in the questionnaire responses. In addition, workload problems and time that can be spent on assessment seems to be especially relevant to core staff, while the associate tutors tend not to experience the overall workload problem that is generated for core staff.

Similar to the course leaders, markers were also aware of varieties of practice and inconsistencies across courses and programmes. The questionnaire results highlighted that some found agreeing assessment standards before marking ‘extremely helpful’ (six participants) or ‘very helpful’ (two participants), while the rest of the participants found it ‘not helpful’ or something that they had not experienced. Again, in common with the course leaders, the focus group highlighted markers’ feelings that there were different practices depending on course sizes with large courses being perceived as more problematic and rushed and, therefore, tending to generate more formulised or strategised moderation systems. Indeed, it was felt that the process that surrounds the moderation system in large courses could lead to stress in the markers’ experience. Furthermore, the forms of assessment moderation deployed were felt by some to lack the rigour of some external systems, for example, those deployed by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) and, in particular, the variability in moderation approaches and also in marking styles was felt, by some, to be problematic in terms of consistency. For example, M1 reflects on her experiences of marking for the SQA by arguing that in the SQA ‘that’s a very rigorous quality assurance and when I came here, I felt that there was not the same rigour to it’.

The 22 point scale – marking criteria that differentiate student performance on 22 grade levels from A1 to H – used by the University of Glasgow, in itself, was seen to be too blunt a tool as it was felt that a precision instrument was more appropriate in the context of mapping learning outcomes to scripts. Ultimately, a (perhaps) hidden issue lay in the anxiety for markers caused by all of these issues combining. This might also contradict the course leaders’ opposition to further regulation, as the markers tended to favour more robust standardisation of practice and clearer guidance on assessment and moderation processes.

While being critical about the inconsistency of practice and the quality of some of the marking systems, there were also positive aspects highlighted by the markers. For example, the aspect of ongoing support tended to be felt to be particularly valuable, especially the opportunity to work with peers. The aspects of collegiality and team support also tended to be highly characteristic of the themes emerging from the focus group with markers. This might confirm Smith’s (2011) argument which sees collegial reflection on assessment moderation practices helping to identify areas for improvement. Markers’ reflections might also suggest that, in order to support the emergence of ‘social moderation’ and the growth of communities of practice, as highlighted by the course leaders in the previous section, some specific actions would need to be undertaken. Simply bringing together staff on a module does not ensure the formation of a community of practice, rather, this requires further effort and attention (Price, 2005). Price argues further that the sharing of standards should be done through methods appropriate for tacit knowledge transfer rather than simply promoting the idea of explicit knowledge in assessment. These methods could be seen in relation to discussions, exemplars, sample marked scripts, model answers but also to the provision of further feedback to markers on their marking (Price, 2005). This might also enhance further the markers’ positive experience of moderation meetings.

Many helpful suggestions for improvement in moderation practices were made by course leaders. Their suggestions tended to address not only moderation practice and the work of markers, but also the wider structural support mechanisms. Firstly, in order to support markers, a number of helpful strategies were outlined that the course leaders could develop:

1. The adoption of formative feedback prior to summative assignments.

2. The adoption of pre-marking moderation: grade mapping to reduce the potential for marker variability, and so a ‘picture’ of what an A grade looks like and how it meets the criteria, would be drawn out for markers and discussed prior to marking. This would be repeated with A-E grades;

3. Collaborative development of standards, followed by dialogue, debate and grade mapping at the moderation meeting itself.

In terms of institutional level support mechanisms, however, a quantitative, statistical overview of assessment results across the courses was suggested as a rough tool with which to check for obvious anomalies across a student’s grades. Furthermore, consistency across years and various courses could be also encouraged by using one year’s scripts as exemplars and cohorts from different years could have grades cross-checked to determine the percentage of awards within the A-E range. Moderation is, therefore, characterised in a number of dimensions: (1) Intra-course moderation principles; (2) Trans-course methods, and (3) Variability of practice across programmes and a number of pragmatic issues in terms of institutional support were identified as necessary developments:

1. Appointing an Assessment Officer in the School of Education;

2. Creating space for more ‘conversations’ on assessment and assessment moderation;

3. Generating ‘formal’ training as part of a CPD programme, especially as ‘a lot of us come with training that we obtained from other work contexts’ (CL6);

4. Pairing staff mentors with new or inexperienced staff.

As regards the last three suggestions, staff development was felt to be a key way of tackling the issue of accurate marking supported through dialogic, co-constructed moderation practices.

Markers also made some helpful suggestions on what might improve the quality of marking and associated assessment. Firstly, they highlighted a number of valuable support structures that align with the suggestions made by the course leaders and that could be developed at course organisational level:

1. The benefits of pre-marking support;

2. The benefits of ongoing support from peers and/or course leaders;

3. Mentoring for new markers;

4. Collegial peer – marking was felt to be helpful, especially for new markers;

5. Annotated exemplars with notation on A-E grades could be provided for all markers. These could be made available by the course leaders for future years and marking teams.

As regards the more institutional and centralised support mechanisms, the markers suggested that there should be a centralised overview and planning of teaching and assessment loads that can be formalised in assessment calendars/programme schedules in order to identify ‘bottlenecks’. Similarly to course leaders, markers would also like to have more time for marking in order to improve its quality. However, markers would also like to see the practice being granted higher ‘status’. It is, after all, in student terms, perhaps the most important role academics perform. According to the interviewees, this could be also achieved by allocating more time for marking, employing more core staff but also facilitating the team work between core staff and associate tutors. Additionally, markers also questioned the allocation principle of marker to papers, a possibility for a development programme that could support new markers (voluntary for more experienced markers) but also the idea of creating smaller teams of markers who are keen to mark and who have a record of consistency.

Based on the small-scale study introduced in this paper, it could be argued that both course leaders and markers experience assessment moderation as a diverse and often problematic part of their work. Both groups tend to be particularly concerned about time – related pressures and opportunities for discussion and collegial practices. Course leaders also perceive their roles as being more pressurised in terms of mediating between the regulations, student expectations and markers. It could be argued, therefore, that the development of “social moderation” (Colbert et al., 2012) and communities of practice in assessment requires further support and research. By focusing on the experiences of course leaders and markers and their suggestions for improvement as highlighted above, a shift from rather isolated practices to collegiality could take place:

it is through ongoing discussion and critiques through a community of practice group that we can progress to developing more valid, fair and reliable assessment of students and reassure higher education regulating agencies the profession and community of the quality of programmes and the graduates produced. (Smith, 2011, p. 48)

The researchers, however, also believe that the experiences highlighted in this paper do not apply only to this particular institution and disciplinary area; they might also represent the voices of many other course leaders and markers across the UK and internationally. Therefore, recommendations for further action are suggested below:

Awareness raising is required among colleagues on the various forms of practice and continuing dialogue on best practice within different marking contexts;

The advantages and disadvantages of each form of moderation require further exploration: pre-marking, post-marking and hybridised forms via CPD, seminars and mentoring programmes to form dialogic communities of assessment practice;

There needs to be further study beyond the School of Education, to capture the full range of approaches to assessment moderation. A cross-college study might best serve this purpose in the first instance, the findings from which might be used to inform practice and policy within the University of Glasgow as a whole;

A larger scale trans-institution project to determine the range of forms deployed nationally or/and internationally would capture trends in the field and further inform policy and research nationally/internationally;

Studies in the field have omitted, perhaps, the most important perspective – that of students themselves. Further studies would benefit from the inclusion of the student voice to create a tri vias approach to further study that encapsulates the trio of perspectives necessary to extend research in this field: course leaders/architects, markers and students.