Angela Sutherland, David Edgar, Peter Duncan, Glasgow Caledonian University, UK

In the United Kingdom [UK] Higher Education sector, internationalising the curriculum is a key tenet of strategies, for reasons relating to income generation and enhancing the employability of graduates. The principle of promoting culturally diverse learning environments is clear; it seeks to embrace opportunity for class discussion, broaden student learning across international contexts and in consequence, enrich the quality of teaching and collective learning to enhance the overall student experience. This principle implies a student-centred approach to learning where knowledge is viewed as being something that is socially constructed and lecturers facilitate students’ learning by nurturing a reasoned interpretation of the world or conceptions of the subject matter (Sadler, 2012).

As the primary architects of student learning (Leask & Bridge, 2013), academics are a key force in a University’s institutional transformation and internationalisation of knowledge. However the degree of priority given by each university, its culture and the level of commitment and attitude of staff towards internationalisation, will directly impact upon the degree of success (Childress, 2010) of implementation of a student-centred international pedagogy (Dole, Bloom & Kowalske, 2015).

Evidence also suggests teaching and support staff are ill-equipped to deal with diverse cohort challenges relating to varying degrees of understanding evident across teaching teams on the differences between students’ educational background, expectations, cognitive maps of education pedagogy and the impact of culture shock on the pace of international student learning (Childress, 2010; Hyland, Trahar, Anderson, & Dickens, 2008). Continuous, appropriate staff development is therefore critical to the successful implementation of an internationalisation strategy (Warwick & Moogan, 2013) and thus the student experience.

Student-centred approaches may involve academics facilitating students through several stages of maturity in their approach to learning, inspiring and challenging students to contribute towards the delivery and in encouraging peer reflection (Sadler, 2012). However, these activities are time intensive and as such, academics must make decisions of depth versus breadth (Dole et al., 2015) and the degree to which the environment is “safe” and conducive to encouraging students to behave like professionals (Lillyman & Bennett, 2014; Sadler, 2012) – all qualities demanded by the international business community. As such, in a business school, a student-centred approach within a safe learning environment may go some way towards achieving the goal of Knight’s (2008, p.21) widely cited definition of internationalisation as a ‘process’, “integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of higher education” and reaping the pedagogic advantages of such a process.

The degree of internationalisation activity across the UK Higher Education sector has therefore intensified in scope and scale, fuelling demand for internationalised courses from students as well as organisations seeking graduates with competencies in international context and cultural awareness (Bennett & Kane, 2011). Higher education institutions strive to create culturally diverse learning environments through inbound and outbound mobility, not only for financial gains, but also to develop international links for teaching and research purposes, enhancing institutional reputation (UK Higher Education International Unit, 2013; Souto-Otero, Huisman, Beerkens, De Wit, & Vujic, 2013) and improving employability prospects of students (Joint Steering Group on UK Outward Student Mobility, 2012).

However, does internationalisation need to occur through exchange programmes? Aerden, De Decker, Divis, Frederiks and de Wit (2013, p.57) would claim not, challenging the value placed on mobility and student exchanges, cautioning that ‘Internationalisation at home’, encompassing internationalisation of the curriculum and the teaching and learning process, is equally relevant in the drive for internationalisation. Mobility is no longer an objective in itself, but a means to reach this future goal and results in a degree of homogenisation of curriculum.

Knight, (2013, p.88) cautions against such homogenisation of internationalisation as a double edge sword in that for quality assurance purposes, courses offered by Erasmus exchange partner institutions must be equivalent to those delivered by the home campus, yet in reality, this provides no room for formal adaptation to allow subject areas and (importantly) pedagogy to conform to local contexts. It is acknowledged that student mobility and associated cultural learning-gains, and the internationalisation priorities of partner institutions are not always balanced across institutions. Some of the inequalities being attributed to short-sighted vision of the dynamics of co-operating institutions, funding shortages and diversity challenges such as language, cultures and other priorities pertaining to academic qualifications; all of which may have constrained efforts towards achieving a European identity (Rachaniotis, Kotsi & Agiomirgianakis, 2013).

Interestingly, Knight (2013) reflects on the weakness evident in her original definition of internationalisation in that traditional values associated with this goal, such as collaboration, mutual benefit and exchange are not explicitly articulated, only assumed. Nevertheless, student mobility and exchange offers a range of benefits including personal growth, confidence-building and helps students develop a more positive, enthusiastic approach towards cultural diversity and thus awareness (Rachaniotis et al., 2013; Souto-Otero et al., 2013). The propensity for exchange students to therefore transition from cultural awareness to cultural intelligence is heightened through physical transfer and experiential learning, studying at the host institution. This makes student exchanges a useful mechanism but it is how they are implemented that can add or destroy the pedagogic value of the international learning experience.

Drawing the preceding discussion together, it is argued that Higher Education institutions in the UK are increasingly turning to internationalisation of the curriculum for the interrelated reasons of employability and income generation. Student-centred approaches to learning, teaching and assessment strategies have to fulfil the needs of both domestic (‘home’) and inbound international students who may have different experiences, expectations, needs and perceptions regarding pedagogy, support and curriculum. While programme delivery centres on the UK educational mode, universities tend to accommodate orientation for all students centrally, as a largely homogenous group. While this is effective to a large degree and the international student’s record high degrees of satisfaction, there is always room for improvement. In this case we introduce the concept of ‘cultural intelligence’ which we believe can further enhance the international student experience.

The aim of this paper is to explore the experiences of inbound Erasmus exchange students to determine if student-centred approaches to pedagogy and curriculum delivery are adequate to meet their needs. A case study of a single module delivered to undergraduate students in the business and management area of a UK post-1992 University is presented. The case study is informed by findings collected from Erasmus students via two interviews and a focus group of six exchange students; as well as other corporate data such as module evaluation data. The data is used to examine possible gaps in the tutor-student pedagogic experience, expectations and perceptions.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Literature is reviewed relating to cultural awareness/intelligence and potential pedagogical and cross-cultural challenges in the classroom. The methodology underpinning the case is then described. The case itself is presented, followed by findings and discussion based on the interviews/focus group. The paper concludes by identifying lessons learnt from the case and possible avenues for future research.

This section of the paper is structured in two main parts as follows: Cultural intelligence, and how to acquire it, is explored. Then literature on potential pedagogical and cross-cultural challenges of incoming exchange students is examined.

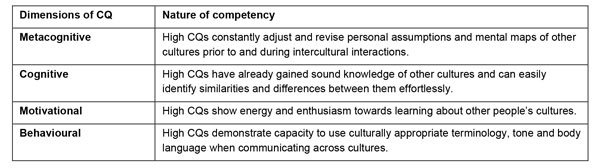

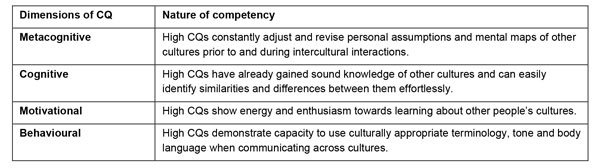

Cultural intelligence (CQ) is a concept from the mainstream business and management context which we borrow for this paper. In essence CQ is defined as “an individual’s capability to function and manage effectively in culturally diverse settings” (Ahn & Ettner, 2013, p. 6) and is composed of three mental capabilities or dimensions, and a fourth dimension portraying overt actions that can be physically observed (see Table 1).

Table 1: Dimensions of Cultural Intelligence

Ahn, M. J., & Ettner, L. (2013). Cultural Intelligence (CQ) in MBA Curricula, Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 7(1),7.

Konanahalli et al.’s (2014) study involving 191 British construction professionals working across 29 countries found that of the four CQ dimensions, motivational and metacognitive CQ contributed more towards cultural adjustment in comparison to cognitive CQ and behavioural CQ. Such insight is valuable in the design of curriculum for establishing relevant learning mechanisms geared towards developing motivational and metacognitive CQs amongst students.

Van Dyne, Ang, and Livermore (2010) also add that cultural intelligence goes beyond cultural knowledge (cf. cultural awareness); it encompasses emotional intelligence (EQ) to be able to decipher between behaviours universal to all humanity, behaviours that are cultural and behaviours that are idiosyncratically personal to a particular individual in a specific situation. Individuals with a high CQ appear to have an ability to interpret another person’s unfamiliar and ambiguous gestures in just the same way that the person’s compatriots or colleagues would behave (Ahn & Ettner, 2013). Whilst cultural differences are apparent in every aspect of business, and thus an in-depth understanding of the local environment is desirable, the CQ challenge can be exacerbated with multiple nationalities working collectively in unfamiliar surroundings (Konanahalli et al., 2014). In essence, this is what the international student exchange seeks to achieve. The next section explores how cultural intelligence is acquired.

Competency in CQ can be acquired through a range of intercultural management training mechanisms including global management training, virtual team facilitation, international merger and acquisition integration and so on (Konanahalli et al., 2014). Within Higher Education, competency can be nurtured by exposing students to unfamiliar terrain and facilitating them through a processual framework of metacognitive thinking which broadens student mindsets and helps them view the world through a different lens. The CQ dimensions (see Table 1) may be useful in the design of curricula for creating challenging group tasks involving diverse teams, which use problem-based and reflective learning approaches to stimulate greater engagement and enthusiasm across the learning environment. Whilst it may be unlikely, within a Higher Education setting, for students to develop all-round CQ competency, the above approach may be geared towards nurturing metacognitive and motivational CQs, to help students transition from cultural awareness to cultural intelligence. However, in the learning mechanisms employed, it is “more important for students to possess a high level of awareness of the self and of others in order to successfully navigate cross-cultural interactions” (Ahn & Ettner, 2013, p.13).

Students from diverse cultural backgrounds with different experiences and cognitive minds seek value from others through informal, yet memorable, information exchanges within the learning environment in their quest for knowledge. Ad hoc interactions with culturally diverse colleagues, inherent in the process of completing group tasks and assignments (where diverse nationalities are deliberately brought together), can augment learning gains from formal class discussions on discipline-specific subjects applied to different international contexts. Leask (2009, p. 207) refers to the “hidden curriculum”; a dynamic interplay of informal, incidental lessons and learning on processes encompassing power and authority relationships, distinguishing peers valued for their knowledge from those best to avoid, student attitudes, behaviours and struggles, both in and out the classroom which shapes the lived experiences of all students.

The hidden curriculum is frequently overlooked (Leask & Bridge, 2013) yet it plays an important role in developing deeper cultural awareness and knowledge on what constitutes effective practice in striving for international infusion. Learning from such intangible interactions may foster greater insight and understanding of working in international contexts and a more ‘broadened’ approach towards managing workplace challenges, which better prepares students for coping with increasingly multicultural and interdependent work environments (Hyland, Trahar, Anderson, & Dickens, 2008).

International and European exchange students have diverse needs and expectations, coming from different educational backgrounds. This creates challenges for incoming students as they try to adapt to new ways of learning, working with others and coping with assessments, and also for the staff who are teaching them (Warwick & Moogan, 2013). Spiro (2014, p. 69) concludes that several studies have revealed apparent “polarised positions” between home and inbound students. The retreat of international and European students into safe and familiar social groups is hardly surprising, given UK academics use language unfamiliar to incoming students such as ‘independent learning’, ‘critical analysis’ and ‘reflective writing’ which is confusing and opaque. Harrison and Peacock (2010, p. 21) encapsulate their findings on the student integration challenges as reflecting “a gap between laudable intention and reality on the ground”. Khalideen (2008, p. 272) refers to this concept as the “contact hypothesis” a fallacy postulating that students from different international backgrounds brought together in one place automatically nurtures cross-cultural understanding and positive relationships.

Inbound students’ expectations of their chosen university regarding service provision, learning gains and the employability benefits from studying in a different cultural setting are determined well before arriving. If actual experiences differ from students’ expected or perceived experiences, gaps are said to exist. As inbound students do not have a complete understanding of the features, pedagogy and assessment process pertaining to their chosen modules, then the reality of the student experience may result in negative gaps in the student learning experience (Nabilou & Khorasani-Zavareh, 2014).

Gap analysis is a well-documented tool for identifying and assessing gaps in the quality of service delivered and in assessment of quality problems for the purpose of continuous improvement. This includes assessment of ‘as-is’ or current processes, versus ‘to-be’ or ideal processes, to determine gaps and develop strategies which will close the gap (Jackson, Helms, & Ahmadi, 2011). Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985) note four possible causes of gaps, two of which are failure to understand customers’ expectations and failure to appropriately manage them. Moving to a new environment is one of the most challenging experiences inbound students endure involving a number of stressors, which may not be immediately apparent to university staff, yet few students seek out support to enhance their social integration on and off campus (Lillyman & Bennett, 2014). Studies investigating interactions between home and international students within the classroom setting also highlight home students experience anxiety and may perceive threats to their academic success and group identity – intercultural contact can be a noticeable concern (Harrison & Peacock, 2010; Dunne, 2009).

Spiro (2014) reiterates the critical role that institutional staff must play in closing the gaps in student expectations, and in integrating different camps of students together, in order to achieve the desired international learning gains. The aim should be to provide a ‘safe’ and comfortable learning environment where students can actively engage and are motivated to learn from experiences encountered (Dole et al., 2015). This can lead to deeper, more sustained learning that can transfer to new situations and problems (Dole et al., 2015). Problem and project-based learning activities may be useful vehicles for developing both CQ and EQ competencies in students. However Dole et al. warn that for all to benefit from this approach academics need to understand “the complexities involved in their new roles as facilitators of knowledge-building rather than transmitters of knowledge” (Dole et al. 2015, p.3).

As the challenges facing inbound Erasmus students are a contemporary phenomenon (Yin, 2009), a single case study of a module containing both home and inbound Erasmus students; and an explicit internationalisation focus was selected. Data was triangulated from module documentation; post-module evaluation data; student marks from summative assessment; empirical research involving Erasmus students who undertook the module via two interviews; and a single focus group of six Erasmus students on the module.

The case study presented below is structured as follows: Setting the scene and the module structure; the pedagogical approach; assessment and feedback; concluding remarks.

The case study module is delivered to Level 3 students at a Scottish post-1992 University over a 12-week period within an overall module time frame of 15 weeks. For the purpose of this paper, the key learning outcome is: appraise the cross-cultural challenges of leadership and management in an international context. The LMD module content includes topics on leadership and soft skills development, cross-cultural working, managing in international environments, career development, ethical decision-making and personal resilience. Two guest lecturers provided supplementary practitioner insight into the importance of developing cultural competencies and personal resilience for working across international environments.

The cohort for the delivery of the module comprised of three student groups (‘camps’): continuing and direct entry (totalling 63 students of mixed ethnic origin) plus seven students via Erasmus exchange. Erasmus is a European Union (EU) funded student exchange/‘study abroad’ programme. Of the seven Erasmus students, one was from Netherlands, one from Spain and five from France. One Erasmus student was female; the other six were male.

Many students undertaking this module had no previous exposure to soft-skill challenges or cross-cultural working. So a pre-requisite for student learning was to create a ‘safe’ environment where students could feel comfortable, confident and sufficiently motivated to engage in class discussion and go beyond current levels of knowledge and soft-skills competence.

At the start of the module after staff gave insight on the structure, pedagogy and mechanisms of learning on the module, students were not keen to share their feelings. Individuals were prompted to give their initial reactions and a general consensus of ‘vulnerability’ was evident along with notable segregation of the different student camps regards seating arrangements.

Staff therefore created a positive learning climate conducive to a ‘safe environment’ by firstly making themselves ‘appear’ vulnerable, in sharing poignant (and harrowing) personal learning curves, which helped shape staff’s knowledge, outlook and perceptions on the value of soft-skills development. Staff, in demonstrating openness, transparency, self-awareness and self-criticism and thus personal growth, together with the explicit prerequisite that experiences ‘shared within the four walls – remain within the four walls’ deemed this platform a key factor in breaking down student barriers, not only to alleviate vulnerability but in engendering collective emotions across culturally diverse students. The importance of this stage was evident in one student’s reflection (Module Evaluation Survey): “XXXX was very good. ... [their] own life experiences were eye opening. Really involved students in the subject and every one felt comfortable”.

In addition to the module handbook, students were issued with a Personal, Professional, Academically informed, Consolidated, Transitional (PPACT) document in Week 1. The PPACT document encompasses a university-wide, student owned process of academic advising which students are encouraged to engage with and complete in their own time and discuss with their academic advisor, either within an individual or group setting. Embedding the PPACT activity into module assessment encouraged frequent recording of poignant learning (reflective accounts of events, experiences and outcomes).

Self-reflection questionnaires were disseminated on the lecture topics where relevant and students were required to submit samples of completed questionnaires as appendices to the Coursework 2 portfolio (see below regarding summative assessment), to evidence reflective learning.

Problem and project based seminar activities were deemed invaluable for nurturing a competitive spirit, motivation and thus enthusiasm towards developing both CQ and EQ across diverse teams. Erasmus students were spread through the teams rather than being allowed to cluster together.

Students were required to plan (for 15 minutes) then submit a competitive bid for the project estimating costs, time and resources used, prior to constructing a tower using Lego® bricks. Teams had to discuss and prioritise critical success factors in competing against other teams for business, keeping to agreed specifications including height, timescales, resources and estimated costs. Nerantzi and Despard (2014) suggest model-making helps individuals and groups focus their thoughts towards a shared goal and in the process, identify creative connections of ideas, experiences and people. As students undertook the activity, staff provided feedback on each team’s dynamics and facilitated post-activity discussion on the importance of planning, control and effective communication.

Teams were to ‘build a house’ with students expecting a similar process and outcome to the previous Lego® construction project seminar. However student peers were covertly assessing individuals and given a guide of factors to consider such as: individual attitudes, power and authority, degree of engagement, team spirit, creativity, cross-cultural challenges, conflict and communication (wording, tone and body language). Peer assessors provided critical reflection on their ‘perceptions’ of what they saw. Students reflected that this activity provided a valuable lesson on different cultural practices and how individuals are perceived by others.

Following Nerantzi (2013) the activities were augmented by short video clips to put lecture topics into context, such as the challenges of working in culturally diverse teams.

The most valuable exercise for cultivating cultural awareness was the use of role-play, where several volunteers took on the role of a manager, employee or work colleague and acted out predetermined scenarios on a cultural-themed problem. The background situation of each ‘opponent’ was hidden from the other volunteers; the rest of the class observed ‘cause and effect’ implications deriving from the role play. Student reflections followed immediately after each scenario, and demonstrated action learning as a result of rashly judging others, as well as active listening to role-players’ responses, use of tone, wording, body language and degree of satisfaction on the outcome reached. Students reflected that this cultural awareness exercise, in itself, was a “complete wake-up call” (Student Reflection). Sutherland and Dodds (2008) conclude that as role play develops critical insight into others’ perceptions and emotions, it is a valuable tool for developing skills needed to deal with conflict.

An important reflection from a pedagogical perspective, is that the desired benefits and learning from all above learning mechanisms, are only possible if a ‘safe’ and comfortable learning environment has been established.

The module has two summative assessments:

Courseworks were marked electronically with feedback provided via the Grademark system. For Coursework 1, feedback was provided in three stages:

1. Generic feedback via e-mail in Week 8, explaining good and poor practice and highlighting areas of concern. Only the coursework average mark was relayed at this stage to stimulate students’ interest on how comments could apply to them.

2. Two days later, individual feedback was provided.

3. Finally, a two hour drop-in counselling session was arranged in Week 9, for students desiring further feedback on comments and concerns raised.

Coursework 2 employed the same staged approach for feedback to students.

To cement learning following feedback from Coursework 1, all students were required to write a half- to one-page ‘plan of action’ to formalise plans (such as attending referencing workshops or up-scaling the quality of sources they used) for improving their future performance. This plan of action had to be included as an appendix to the Coursework 2 portfolio, to evidence actions (planned/undertaken) for self-development. This component was summatively assessed, together with evidence of learning gains from the self-assessment questionnaires.

The cohort received their Coursework 1 marks, feedback and the average cohort mark of 49%. However the average of the Erasmus students was lower at 32% (where 40% is the pass mark). Erasmus exchange students immediately raised concerns about their poor performance. Students were surprised with their results and one reflected he was “absolutely devastated”. To explore the students’ concerns further, two individual interviews and one focus group (six students) were held with members of the module team. As a consequence of these meetings, the following interventions were put in place to provide further support to Erasmus students in helping them understand the pedagogical (and other) requirements for Coursework 2:

1. A one hour intervention session to provide further feedback and explain expectations required for Coursework 2. The intention was to bridge any ‘expectations gap’ students may have had on considering their results from Coursework 1.

2. A series of Erasmus student support sessions were arranged with Academic Development Tutors relating to academic writing and citation/referencing good practice.

3. Erasmus exchange students were given the opportunity to submit first drafts to the module team prior to formal submission on the understanding that students would only receive comments on concerns relating to structure, depth of analysis, breadth of reading and referencing.

The purpose of our paper was to explore the experiences of inbound Erasmus exchange from several EU countries to determine if student-centred approaches to learning are adequate to meet their needs. This section explores this and the possible student pedagogic experience, expectations and perceptions. The findings are split into two sections based on methods used – Erasmus exchange focus group and in depth interviews with two students. As discussed above, this data was collected following Coursework 1.

The one hour focus group revealed that the students were results and performance driven. They highlighted immediately, concerns about their poor performance following Coursework 1, expressing:

Way of[f] mark. Don't take in account that our way to present in our home country is not the same than in UK. (For exchange student). It's a critic about general exchange more than module. We are not informed on the way to work.

The huge problem with this module is that as a French student, the criteria of notation are completely different from the French educational system. The other French people and I had a terrible first assessment grade compared to the effort we put in. Our consideration and learnings of what a well written essay should be didn't match at all with the expectations of the one of UK. More awareness about what we're supposed to do and how we're supposed to write it would have been a big help.

These results clearly demonstrated that while the infrastructure and processes may be in place, the expectations are not aligned between tutor and student.

These results were repeated across many responses from the focus group and highlighted the need for an additional intervention to support exchange students. One exchange student, who failed to submit his coursework at the first diet, was questioned further in the focus group about his non-submission. He explained he was under too much pressure with assessments on the other modules, and did not want to risk failing them all. Therefore he took the decision to forego LMD assessments and submit these coursework instead, at the resit diet. This student attended all intervention support sessions arranged for exchange students following Coursework 1 results, and at the resit diet, passed assignments at 53% and 55% respectively.

The focus group revealed some interesting themes which were explored more fully in the interviews. Findings from two 30-minute interviews involving a French and a Dutch student revealed strikingly similar problems. Whilst many issues were raised, key concerns were summarised as follows:

The results for the interviews highlighted a series of process issues but again re-enforced the importance of aligning student and tutor expectations. Clearly a ‘consumer gap’ is evident and needs to be addressed.

Findings indicate that the processes and procedures put in place to support Erasmus students in navigating UK pedagogic styles, assessment and curriculum may be insufficient to truly support the student journey in a way that student centeredness would imply. Key areas of discord revolve around curriculum structure, assessment style, expectations and pedagogic approach. In essence, the cognitive and intangible processes and aspects of the student journey are problematic with evidence to suggest that poor cross-institutional communication and generic orientation compound the challenges.

Despite these issues, pedagogical benefits of a continuous learning approach across the module were apparent, with a 5% increase in mean score between Coursework 1 (49%) and 2 (54%). However, of particular significance was the 20% increase in the mean score across Erasmus exchange students’ performance, from 32% to 52% respectively following the targeted interventions detailed above. This is significant as it reflects the impact of bridging the expectation gap between the tutor and the student.

From the research it was clearly evident that the findings reflected Nabilou’s findings (2014) around ‘negative gaps’ in that Erasmus students were steadfast in their conviction that there was a considerable gap in terms of their expectations of how to tackle module assignments, as these were disparate from what they had been taught in their home institutions.

To date, very little (if any) mechanisms are in place at many UK institutions to address this gap and equip exchange students with the support and insight required to enable them to perform at their best level. Policy is now being reviewed (at School level) with strategies already in place to provide bespoke support for Erasmus and inbound students and thus enhance the international student experience further. This activity contradicts Norton’s (2009) conclusion that university policies on teaching and learning are often imposed by management via a top-down perspective who rarely use pedagogical evidence.

The research also highlighted the strategic learning nature of the student and the challenges this poses for filling the expectation gaps. Examples included Erasmus students seeking to undertake two ‘very similar’ modules through the exchange process and managing to do this due to limited cross-institutional communication and ‘hazing’ of the module mapping process. Indeed strategic learning is clearly evident in that while Erasmus students are keen to learn, they are unlikely to engage in perceived periphery activities such as induction, cross-cultural integration and the completion of reflective journals, especially when students are struggling to cope with assessment challenges. These are importance vehicles for the development of both EQ and CQ and therefore need to become embedded within the curriculum. So, while Dunne (2009) concludes that students should be forced to work together to encourage social integration, it is clear that students try to avoid this process if it is peripheral to them passing. Staff can therefore facilitate this process and exploit learning tools such as problem- and project-based learning and role play to galvanise student engagement and thus develop cultural and soft skill competences; and hopefully break the strategic learning cycle.

The initial project has highlighted many avenues for further research and activity that can provide additional insights as well as address current challenges. For example, the School currently runs a series of workshops for postgraduate students which adopt a staged approach to students learning regarding CQ, namely:

Core to the delivery of these workshops is the DEAR framework (developed by staff), an acronym for Description, Evaluation, Alternative meanings and Reflection. The tool can be used to facilitate reflection and learning in relation to Ahn and Ettner’s dimensions of CQ (see Table 1 above; Ahn & Ettner, 2013). The workshops programme could be extended to include undergraduate students at Level 3 thus meeting cross-cultural challenges of international exchange students. Further exploration of the structure and pedagogy of the LMD module would ensure strong mechanisms are in place to nurture both EQ and CQ competencies for students and help encourage students to develop both reflective and reflexive approaches.

Overall, it is clear that universities need to embrace more student-centred, reflective and reflexive approaches for supporting Erasmus students within the classroom setting and encourage better integration of students from different backgrounds, thus encouraging greater engagement towards development of cultural intelligence. Understanding how to develop these specialised skills and abilities across a diverse student body (home students, direct entry students, exchange students and so on) is key to producing ‘21st century ready’ graduates.