Sabine McKinnon, Anne Smith and Julie Thomson Glasgow Caledonian University, UK

The process of internationalising higher education in the UK has been subject to lively debate for over 20 years. During this time the discourse has often focused on the needs of international students in a UK classroom. The Higher Education Academy’s Teaching International Students Project (2009–2011) which was funded by the Prime Minister’s Initiative 2 (PMI2) provided a comprehensive resource bank of materials to assist academics in teaching international students (Ryan & Pomorina, 2010). Meanwhile, academic literature has presented many examples of good practice, toolkits and advice on supporting international students in their learning (Carroll & Ryan, 2005; Jones & Brown, 2007; Ryan & Viete, 2009; McKinnon, 2013). Organisations like the United Kingdom Council for International Students Affairs (UKCISA) and the British Council have organised high profile events to draw academics’ and students’ attention to the impact international students have had on campus life (UKCISA, 2008).

Whilst these initiatives have been welcomed by the higher education sector, it must be recognised that international students are still a minority at British universities (British Council, 2015). They have already taken the first steps towards widening their cultural horizons by deciding to study outside of their home country. What about the vast majority of our home students who are often local and have not taken up the opportunity to take part in international exchanges or study visits? It is well known that UK mobility figures are still low. The latest data shows that there remains a significant gap between the 493,570 foreign students that the UK hosted in 2013/14 and the 20,064 it sent abroad that year (Carbonell, 2014; British Council, 2015). Statistics from the European Union’s ERASMUS exchange scheme reveal that UK participation has increased steadily since 2007 but it still ranges at the lower end of the spectrum of the 33 nations in the programme. In 2011–12, 2% of the total number of UK graduates had taken part which is 3% below the European average (European Commission, 2014).

There are many explanations for these numbers ranging from financial issues to a lack of foreign language skills but they make it abundantly clear that we cannot rely on physical mobility alone to give our students an international experience. As a result the idea of ‘internationalisation at home’ has grown in importance. First coined by Nilsson in the late 1990’s it refers to learning and teaching activities that increase the cultural awareness of non-mobile students (Nilsson, 2000; Wächter, 2003; Teekens, 2006). Using technology to connect students and staff with their peers in different countries is one of them. It has turned out to be “one of the most important vehicles” for internationalising higher education (Joris, van den Berg & van Ryssen, 2003, p. 94).

Amongst the many different initiatives at national and international level (Killick, 2014; Soria &Troisi, 2014) the Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) method, which has been tried and tested by the State University New York (SUNY) and their 40 international partners over the past 10 years, is one of the most recognised in the field (De Wit, 2013). It uses internet-based tools and innovative on-line pedagogies to engage students and their teachers in sharing their learning irrespective of their geographical location thus adding a global dimension to the teaching of the discipline. Integrated at module level the collaboration can take place over short periods of 4-6 weeks or throughout the entire module. In some cases the teaching is fully on-line but most often it is delivered in a blended format; i.e. alongside conventional face-to-face sessions.

This paper presents the results of a pilot study in entrepreneurship education at Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) which used the COIL method in a third year module. It reflects on the benefits and challenges for students and staff involved and makes some generic recommendations.

Despite significant studies which have developed an understanding of entrepreneurship education (Fayolle & Gailly 2008; Smith & Paton, 2010; Wing Yan Man & Farquharson 2015) the question of how we internationalise the actual enterprise experience for students in the classroom needs further investigation. Although internationalising entrepreneurship education is part of the wider internationalisation agenda some aspects make it problematic; specifically cost and sustainability which was highlighted by Smith and Paton (2011) in a study of pedagogy and transnational entrepreneurship education.

It is well known that entrepreneurship education benefits from experiential learning approaches and delivery of authentic experiences (Bandura 1977; Kolb 1984; Cooper & Lucas, 2007; Pittaway & Cope, 2007). Such approaches require the creation of learning environments where students are encouraged to engage in entrepreneurship activity themselves through simulations, a wide variety of business projects and simple trading experiences (Pittaway & Cope, 2007; Fayolle & Gailly, 2008: Smith & Paton, 2010). We therefore need to provide an equally authentic international learning experience which brings students’ cultural sensitivity to the fore and addresses it explicitly in the taught programme.

Literature on entrepreneurship education emphasises the importance of learning opportunities which require students to draw on a number of transferable skills which include communication, self-efficacy as well as more cognitive behaviours and heuristics as discussed in depth by Cooper and Lucas (2007) and Smith and Paton (2011). The aforementioned studies posited that social learning, authenticity and communication play an essential part in the learning environment. Addressing intercultural skills and attitudes explicitly through authentic cultural interactions with peers in a different country adds a new dimension to the entrepreneurship education model. Based on Deardorff’s model of intercultural competence (Deardorff, 2006) intercultural skills include the ability to show patience and perseverance in interactions with members of a different culture and attempting to interpret the world from a different point of view. Intercultural attitudes include respect for other cultures, curiosity and viewing difference as a learning opportunity.

Traditionally we have relied on optional participation in international student exchange schemes or study visits rather than on integrated learning outcomes, which are part of the taught curriculum at home (Fayolle & Gaily, 2008). To internationalise the entrepreneurship education toolkit, learning environments need to contain real-life cross-cultural experiences (Smith & Paton, 2011). Authentic international group work becomes part of the social learning required for successful entrepreneurship education. Given that student mobility figures remain low and even short study trips abroad require substantial resources, technologies can offer more cost effective routes to internationalise the entrepreneurship experience. Universities provide IT support at central or departmental level anyway so that the use of Web 2.0 tools for teaching does not add a significant extra cost. Smith, Halcro and Chalmers (2010) trialled such tools as a method for connecting students in the UK enabling communication and social learning to occur. Based on that experience it was decided to extend this to collaborative working with their peers in a different country on the other side of the world.

GCU and Kansai University in Osaka, Japan, are members of the COIL Global Partner Network which is coordinated by the COIL Center at SUNY, New York. Initial contacts were set up between the two institutional COIL co-ordinators who were looking for international partnerships in entrepreneurship education. Situated in Japan’s second biggest city Kansai University offers a portfolio of programmes (Business, Computing, Engineering, Law) that are similar to GCU’s. The majority of students in both institutions are local and have very limited experience of travelling or studying abroad. At GCU between 1% and 2% of students participate in formal mobility schemes.

Keen to enhance their students’ international experiences academic staff in both institutions turned to the COIL approach as an effective way of internationalising their curricula. At GCU a strategic change initiative called ‘Global Perspectives’ supports staff to integrate global learning activities in their taught programmes which is required by the university’s Strategy for Learning (Global Perspectives, 2015). COIL is being promoted across all schools in the university as part of the initiative.

The COIL collaboration was trialled in a third year undergraduate module called Entrepreneurship in Developing Organisations which was delivered to 64 students in the first trimester of the 2014/15 academic session. Of the cohort, 83% were articulating students from local colleges who had only just started their studies at GCU. Their prior international experience was limited. Only one student had taken part in an ERASMUS programme in France. A pre-pilot survey revealed that 89% had never lived or worked abroad. The planning process for the design of the collaboration involved regular discussions through e-mails and Skype calls between the teaching team at GCU and the COIL coordinator at Kansai University. Issues such as choice of module, student cohort and platform for the collaboration needed to be addressed in advance.

The chosen module aimed to introduce students to the theory and practice of entrepreneurship and innovation. They were required to examine and analyse the process of entrepreneurship and to apply it in developing firms. Allocated to groups of four or five the students were asked to select an innovative company operating in the food and drink sector which had a trading history between Japan and Scotland. They were required to research the innovative activity of their chosen company such as the types of innovations they had selected and how they subsequently commercialised and marketed them. Students were encouraged to pay particular attention to the impact of cultural differences on the innovative practice between Japan and Scotland. Five cross-cultural teams were formed, partnering 21 students from GCU and 13 students from Kansai. The remaining students worked on the same project but they did not collaborate with their Kansai peers directly. All groups were required to produce a 1,000 word report about their findings displayed on a wiki platform which was worth 30% of the overall grade for the module.

Having assessed a number of different Web 2.0 platforms the teaching team decided to use Wikispaces, Skype and Facebook to enable collaborative working. Students from both universities were expected to add content to the wiki on a regular basis during the six weeks of the pilot. A Skype call with students and staff at Kansai and GCU took place at the start and the end of the project. Students were encouraged to arrange their own Skype calls to communicate with their Japanese team members throughout the pilot. They were given timetabled access to the university’s Skype suite. All students were invited to join a Facebook group where they could get in touch with the Kansai students even if they were not allocated to the cross-cultural teams. They were very comfortable with the Facebook platform and interacted with their Japanese peers on a regular basis to discuss aspects of the task.

Pedagogic literature on technology enhanced learning and teaching stresses the importance of clear instructions to support students in using technology (Ringstaff & Kelley, 2002). Students were, therefore, issued with a guidance document which provided additional instructions on the use of the wiki technology platform, useful tips about working in groups and an outline of weekly tasks. They were encouraged to assess their progress regularly and reflect upon how their group had performed each week.

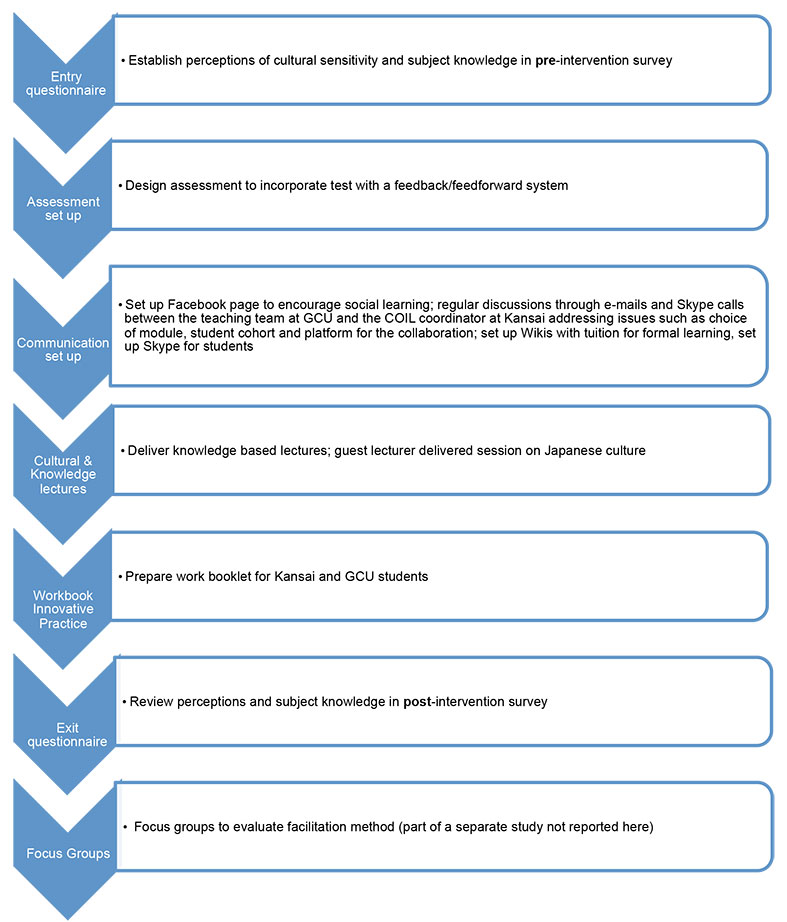

Figure 1 provides an overview of the pilot design.

Figure 1 Overview of pilot design

Discussing the required preparation for the intercultural interaction GCU staff were aware that the Scottish students’ knowledge of Japanese culture and society might be limited. The pre-pilot survey revealed that 82% felt that they knew very little or had only a basic knowledge. As the enhancement of their cultural awareness was one of the key objectives of this study and they were about to start working with their Japanese peers directly, additional support was required to prepare them. Joris et al. (2003, p. 105) point out that intercultural differences are “not a small matter” and that students (and staff) need to “understand what is happening”. It was therefore decided to engage a specialist in Japanese life and culture who delivered a two hour guest lecture before the pilot started. Student feedback was very positive. It was found useful by 77% of students because it helped them understand the society their peers come from.

The data collection process for the evaluation of the COIL collaboration was based on informed consent. GCU students filled in an online questionnaire before and after the pilot. The introduction to the questionnaire assured them that their participation was voluntary and that their responses would be treated confidentially in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. In addition the formal Faculty processes for ethical approval were followed. Content was posted on the Module Virtual Learning environment (VLE) advising students about the project, the purpose and objectives and that by taking part, their academic performance in the module would not be affected. The survey instrument was sent to the Kansai COIL coordinator but due to administrative difficulties it was not used at their end. As a result only the GCU responses are presented here.

Students were asked to assess their own knowledge of Japan, their general cultural awareness and their intercultural skills. The section on intercultural skills was divided into six sub-sections which set out in separate statements what these skills involve and asked students to map their own abilities against them. They were asked to agree or disagree with statements such as “I can adjust my speech if international team members do not understand me” or “ When working in an international team I make an effort to find out as much as possible about the country of my international team members”. A five item Likert scale (strongly agree/ agree/ neither agree nor disagree/ disagree/ strongly disagree) was used for these questions. Other sections of the questionnaire contained yes/ no and open questions which asked for comments to explain the participants’ responses. All students in the module took part in the evaluation but for the purpose of this study only the responses from the 21 GCU students who worked in cross-cultural teams with the Japanese students (Group A) are presented here.

The response rates were high. 90% of the students in group A submitted a response for the pre-experience survey. 67% of the group responded to the post-experience questionnaire. The demographics of the sample include that 89% of them were articulating students. 95% were UK nationals. None of them had studied abroad. 63% did not speak a language other than English. 21% had basic foreign language skills. This paper focuses on some representative results to outline the universal lessons learnt from the pilot study.

Additional data was collected from semi-structured interviews with the two teaching staff on the module who had designed the pilot. The interviews focused on their perceptions of the benefits and challenges of integrating a COIL collaboration. They gave their permission to be recorded.

The overall student response to the pilot was positive. It was stated by 77% that their knowledge of Japan had improved as a result of the experience. The guest lecture on life in Japan received particular praise. All students felt that it helped them gain an insight into Japanese society and prepared them for working with their Japanese team members.

Of group A respondents, 62% reported improved intercultural skills overall. Comparing their responses to the same skills statements before and after the pilot reveals that there was an improvement in the percentage of respondents who ‘strongly agreed’ with them; i.e. they felt that their confidence in their own abilities had increased. Examples include an increase from 29% to 38% on feeling comfortable working with non-native speakers of English, from 13% to 31% on making an effort to find out about their team members’ country and from 29% to 39% on adjusting their speech if international team members do not understand them. Whereas 29% reported a basic knowledge of Japan before the pilot 85% did so afterwards. While these percentages provide some insight into the students’ perceptions of their own progress they must be treated with caution though because the impact of a six-week learning experience is bound to be limited.

When asked to comment on their COIL experience in an open question they emphasised that they had increased their understanding of the challenges involved in communicating across national cultures.

I think I have been able to understand the difficulties of communicating with people from other countries because their understanding of certain issues is different from mine.

(Conducting business in Japan) is very different from Western ways; to be successful in Japan one would require a very good prior working knowledge of cultural sensitivity and awareness. As a result of this module I actually feel it is something I could go ahead and do with much more confidence than before.

Working with their peers from Japan made the students aware of how their own culture and Western business practices might be perceived in Asia. “Be humble and respect your peers’ views and opinions. Don’t be too brash or boastful.” was the advice from one of them. When asked what can be learnt from the Japanese way of conducting business they commented on the need for patience and “the building of sound relationships” with clients before trading with them. The students noticed different understandings of politeness. While some of them felt that Scotland “needs to adopt” a more polite business etiquette, others reported a sense of frustration because their Japanese team members “should be more straight in the way they communicate with others”.

The students emphasised the generic lessons that had been learnt. “To persevere in the face of adversity” refers to some of the technical difficulties and English language problems the students needed to manage independently. Setting up Skype connections with team members in a country with an eight-hour time difference also proved challenging at first.

There was consensus though that the experience had been worthwhile because it enhanced their understanding of international business in general and innovation and entrepreneurship in particular. “It has opened my eyes to see that not all countries view ‘innovation’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ in the same sense. For example something that is viewed as innovative in this country may not be in Japan due to different levels of technology and experience”. As a result of the project, 62% felt that they had changed their views on innovative companies.

While the survey responses revealed great enthusiasm, students were also aware of the challenges involved. The main issue was the mismatch between the student groups in the two countries. While the GCU students were assessed on the compulsory joint task and the quality of their team working, participation for their Japanese peers was voluntary. As a result the levels of commitment in the two countries varied. Some of the Japanese students left their team early and did not always contribute to the wiki. The GCU students in the affected teams felt let down and more stressed than others in the module. When asked whether they found it stressful to work with international peers, 46% of group A agreed or agreed strongly to feeling stressed. They appreciated though that their teachers gave them the required support in the regular face-to-face seminar sessions to help them manage any anxiety as and when it occurred. Getting to grips with some of the technology involved (Skype and Wikispaces) was perceived as challenging at first because of a perceived lack of institutional IT support but once the discussions got under way the students were comfortable in using it.

The academic staff interviewed were the designers of the pilot. They chose COIL to introduce their students to a world they would not normally have access to. Aware that local articulating students often lack the resources and the confidence to travel they were anxious to help them take the first steps in the process of “building a global mindset for a global economy” without having to leaving the Glasgow classroom. As these students had no prior experience of studying at a university, introducing them to COIL at such an early stage in the academic year was an opportunity to shape their expectations of what learning in higher education should involve. Using technology to collaborate with international peers was an exciting and motivating experience because it was new to them. The “novelty factor” was emphasised by both interviewees. The module was the only one with a COIL element on the GCU business programme which made it particularly attractive.

The benefits to teaching the discipline (entrepreneurship) was a powerful argument for engaging with COIL. This particular module has a long history of innovative teaching practice. Experiential learning has always been at the heart of entrepreneurship education at GCU and in particular in this module because it simulates the enterprise environment in the real world. The module leader pointed out that “we are trying something innovative each year… we are all learning something new.” Challenging yourself, taking risks, overcoming unexpected obstacles on your way to success is an integral part of entrepreneurial behaviour. Participating in a COIL collaboration practises the very same skills. She recalled a situation when the students were anxious because the technology did not work and the communication with their Japanese team members did not go to plan. “The problem is that the students might get upset. This doesn’t work. What now? But that is entrepreneurship”. “Being willing to change step” as and when required is an essential quality for budding entrepreneurs and university students alike.

The importance of managing potential risk figured prominently in the interviews. Staff were aware that careful planning of the educational experience was required to avoid disappointment and disengagement from the students. The module design process was compared to “drawing a box”. “You (as an academic) draw the lines in exactly the way you want it and then you tell the students ‘you function in there’.” The importance of a plan B or a “rescue plan” was emphasised. In the context of this pilot, students could achieve the learning outcomes in different ways. COIL was only one of them. As a result there were no student complaints at any stage of the collaboration and the grades achieved mirrored those of previous years.

When asked about the challenges of this particular project with Kansai rather than COIL in general the interviewees referred to difficulties in the joint planning process. As it was the institutional COIL coordinator at Kansai rather than their academic subject specialists or lecturers who led the collaboration there was not always sufficient discussion on the details of the syllabus, learning styles, assessment, criteria for choosing the students or approaches to supporting them. Whilst the academics at GCU provided their students with advice and facilitation on a regular basis that level of support was not always obvious in the Kansai class due to their own arrangements. It was discovered in the final Skype meeting with both classes that the Japanese students did not always understand the English terminology or the implications of an independent learning approach which they had not come across in their own university before. The COIL guidelines issued by the COIL Centre emphasise the importance of allowing sufficient time for the planning stage but this pilot was arranged at fairly short notice so that regular online meetings were not always possible. The lessons learnt will guide our approach to the next COIL collaboration.

The pilot showed that the integration of COIL into an existing module worked well. It was a valuable learning experience for staff and students alike.

The students viewed the COIL intervention as a ‘normal’ learning activity which is part of the university experience. It was not bolted on to the module or promoted as radically different from other forms of experiential learning. COIL was part of a mix of learning and teaching activities which combined traditional face-to-face lectures and seminars with the online work. Careful support and encouragement from the GCU lecturers helped students overcome their initial anxiety over the use of new online tools.

The importance of thorough planning for the COIL experience cannot be overstated though. Despite developing a detailed plan for the design of the pilot (see Figure 1) there were some unexpected challenges which led to some incidents of failed communication (O’Dowd & Ritter, 2006, p.624) in the online interaction between the students and between the academic staff. They might have been avoided if the basic assumptions underlying the collaboration had been discussed in more detail in advance.

It must be remembered that COIL is a learning journey for everybody involved. Hauck (2007, p. 220) emphasises that “areas of conflict and misunderstanding can be turned into key moments of cultural learning for both tutors and learners”. There is no doubt that such learning was achieved in this pilot. The students realised that intercultural competence cannot be acquired by one six-week intervention. “My knowledge of Japan has improved but their culture is so different from Scotland’s – I feel that there is probably more to learn over a longer period of time.”

Preparing and monitoring the COIL experience on both sides is effectively a team teaching effort across national borders and university systems. As Hauck (2007) points out it is not always easy to achieve agreement on teaching and learning styles amongst colleagues in one institution and one country. If the team members come from two very different cultures, have never met face to face and rely on online exchanges alone “dissonances in interpretation of student behaviour and tutor interventions” can occur (Hauck, 2007, p. 218). That was the case here as only the two coordinators knew each other and the lecturers in Japan did not take part in the negotiations directly. Experience from a different COIL pilot in GCU shows that a personal relationship between the academics in the two countries which exists before the COIL project starts can lead to smoother collaboration. The guidelines issued by the COIL Center at SUNY point out that two-thirds of European academics who are involved in COIL activities found their partner through their own network of contacts. Meeting colleagues at conferences or through research collaboration is often the best starting point for discussions about a COIL project. Despite these difficulties the staff were inspired by their experience with the Kansai project and have already started planning a new COIL collaboration with a different partner in a different module.

As O’Dowd and Ritter (2006) point out it is important to allow sufficient time for a pre-exchange risk assessment to address factors of potential dysfunction in online collaboration. Differences in the motivation and expectation of individuals are classified as ‘high risk’ in their framework. Based on their previous experience of using technology with international collaborators the GCU staff in this pilot had an understanding of risk management in such projects. They therefore made a special effort to make sure their students were not disadvantaged by the uneven levels of commitment to the international group work. Less experienced staff would need to be aware though that careful risk assessment in advance will avoid potential problems down the line. It is also important to include the university’s IT support staff in the planning process from the start rather than just turn to them in times of ‘crisis’ once the module has started.

Other recommendations include securing support from senior management who can encourage other colleagues in the department to use COIL in their teaching so that it is no longer a ‘one-off ‘ experience for very few students and staff and growing COIL expertise can be shared. Liaising with the university’s International Office to explore existing international partnerships for sourcing COIL partners would also be worthwhile.

The limitations of this short pilot lay in the lack of evaluation data from students and staff at Kansai University. Their coordinator contributed regularly in the planning stage but could not be as involved throughout the module due to other demands on her time. As a result the evaluation surveys were not sent out to the Japanese students. It would be worthwhile to compare the responses from both partners in a future study on COIL’s impact to obtain a complete picture and contrast different national responses.

When reflecting on the learning achieved in this pilot it is important to remember that there were many variables involved because these articulating students were new to online learning, direct international collaboration and any form of experiential learning. Which aspect had the most impact would need to be explored in a separate study.

Assessing the overall success of the pilot is complex. Hauck (2007, p.221) challenges the idea of using concepts such as ‘success’ or ‘failure’ and suggests replacing them with “relative awareness gain”. How that gain will translate into actual behaviours in the global workplace or in students’ private lives remains to be seen.