Nell Buissink, Auckland University of

Technology, New Zealand

Samuel Mann, Otago Polytechnic, New Zealand

When we ask educators about their experiences of seeking formal ethical approval for their own pedagogical research, they tend to give us words such as strained, impossible, constraining, difficult, frustrating, daunting, fraught, inadequate and redundant. When we ask the same educators what they would like to be able to say when they think about their experiences with pedagogical research and ethics, they say things such as eye-opening, empowering, lived, enlightening, reflexive, helpful, supportive and ongoing.

Many pedagogic researchers view the formal ethical review processes as a “bureaucratic hurdle” (Chang & Gray, 2013). One way to address this is to look beyond existing formal processes to the underlying thinking, practices and philosophies that the “bureaucratic hurdle” is trying to capture. That is, what is really happening in contemporary learning spaces and what are the ethical issues that need to be captured or considered for the formal ethical review process to generate positive experiences for applicants?

The paper begins by briefly providing some background, and tracing the development and early application of a model designed by the current authors to enable an exploration of the ethical systems at play in contemporary learning spaces (Smith, Frielick, & Mann, 2014). It will then go on to consider some issues raised, as well as identifying future plans for application and development.

Pedagogic research has been described as a fundamental obligation of all university teachers, in that regardless of discipline, all faculty members have a basic professional obligation to both maintain a familiarity with current research in learning and teaching and to participate in pedagogical research (Pecorino & Kincaid, 2008). With growing pressure to publish, and to continually improve teaching, there has been an increase in the number of academics from across all disciplines wishing to undertake research into learning and teaching (Gibbs, 2013; Harland, 2012; Kember, 2003). How can institutions – and their personnel, structures and policies – best support those undertaking pedagogic research?

Pedagogic research tends to come under the qualitative umbrella (but not always), and for a long time qualitative researchers have created their own set of ethical considerations that have often challenged formal ethical processes which tend to be based on bio-medical models (see, for example, van den Hoonard [2011] and van den Hoonard and Tolich [2014]). Importantly for this discussion, characteristics of qualitative research that impact upon ethical considerations include an open-ended approach (i.e. not testing a hypothesis) and a more involved relationship between researcher and the participants (i.e. not researching ‘subjects’ in a short visit to a laboratory or a neutral place). Added to this, pedagogic research (both qualitative and quantitative – especially with the dramatic increase in ‘big data’ quantitative mining of students) takes place in circumstances – contemporary learning spaces – that create a further set of ethical considerations. Such ethical issues in pedagogical research are underpinned by the evolving nature of learning and teaching, as well as factors such as the changing role of research and technology in higher education.

The intention of the model is to provide a visual tool for a deep exploration of ethical relationships and issues in learning spaces (Smith et al., 2014). It is hoped that educators can apply the model to their own learning spaces to help paint a picture of both documented and relatively unexplored ethical issues in learning, teaching and pedagogical research. This section will consider some of the thinking behind the development of the model and will be followed by a discussion of findings from early testing, as well as future plans for application.

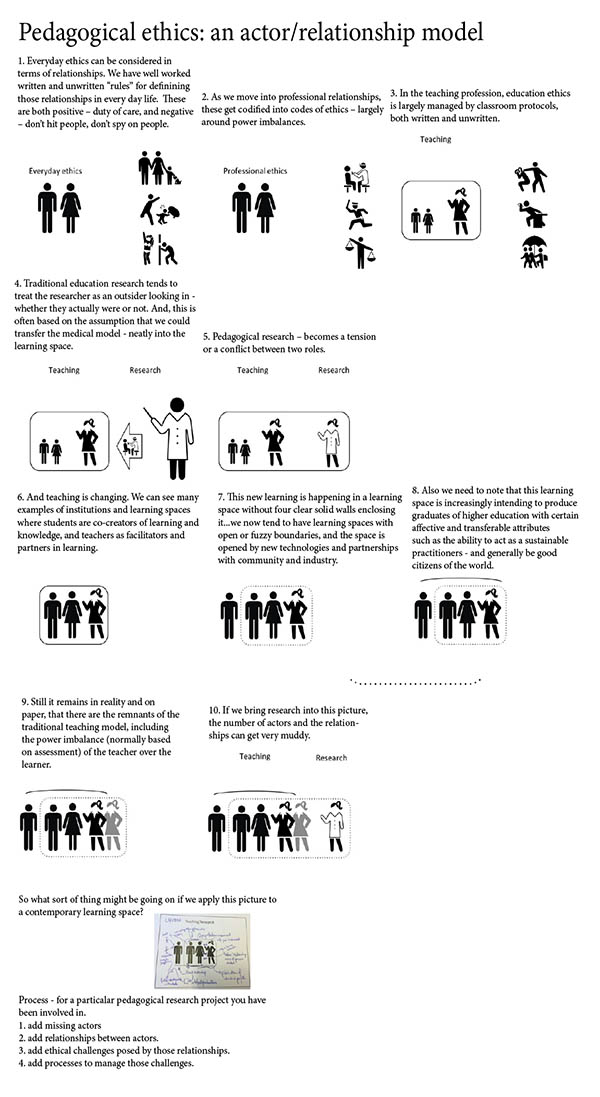

The thinking behind the development of the model is graphically presented in Figure 1, and it is also briefly explained in this section of text.

Figure 1 Development of the model

Ethical considerations are not just reserved for research or learning spaces. Everyday ethics can be considered in terms of relationships (Jickling, Lotz-Sisitka, O'Donoghue, & Ogbuigwe, 2006). We have well-worked ‘rules’ for defining those relationships in everyday life. These are positive – ‘duty of care’, and negative – ‘don’t hit people’. As we move into professional relationships, these get codified into codes of ethics, based largely around power imbalances. Traditionally, in the teaching profession, education ethics has largely been managed by classroom protocols, both written and unwritten. The traditional classroom environment supports such protocols by providing conditions in terms of both space and relationships that are widely understood and set within clear boundaries – a closed classroom, interaction largely contained within the four walls, and interaction primarily based on the knowledge supplied by a dominant teacher figure. A pedagogical researcher in this traditional picture – even a teacher-researcher – tends to be treated as an outsider looking in, and this is where we can see the basis of the assumption that a bio-medical model of ethics could be transferred and applied to an educational setting. Many formal ethics processes including forms and guidelines appear to be based on a premise that research is being done on strangers with whom we have no prior relationship or plan for future interaction (Murray, Pushor, & Renihan, 2012).

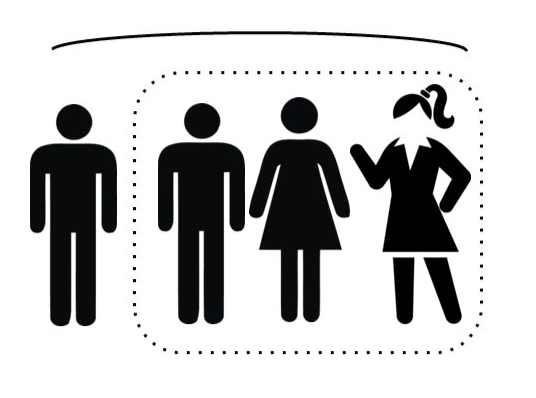

In recent years, many learning spaces (across geographical and education-level boundaries) have moved away from this traditional picture, with implications for learning, teaching, researching, ethical relationships and formal ethical review processes. Some of these changes are increasingly being noted as features of contemporary, future-oriented learning spaces, including teacher-as-facilitator, classroom boundaries opening up, the use of open technology and a focus on affective graduate attributes. As well as this, pedagogic research is increasingly coming from an exploration from the ‘inside’, done ‘with’ the participants rather than ‘on’ them. This contemporary learning environment is graphically represented by the authors in the ‘base’ model (Figure 2).

Process: For a particular pedagogical research project you have been involved in: 1) add missing actors; 2) add relationships between actors; 3) add ethical challenges posed by those relationships; 4) add processes to manage those challenges.

Figure 2 Base model of pedagogical ethics: A visual tool for an educator to start exploring the ethical systems at play in future oriented learning spaces.

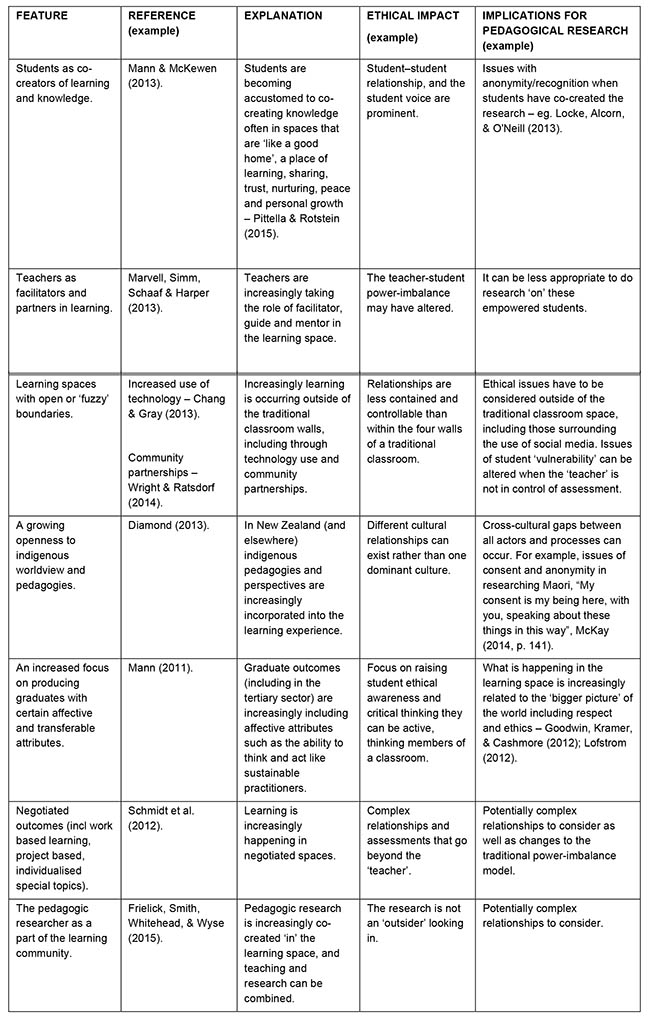

It is the intention that the base model is applied to identify unexplored, underexplored or context-specific issues as well as those related to features of contemporary learning spaces that may be at play in ethical systems and relationships. Literature in this emerging area can point to some examples of the sort of ethical issues that may arise through the application of the model (Table 1).

Table 1: Literature in this emerging area can provide examples of the sort of ethical issues that may arise through the use of the model

A number of interesting observations relating to the applicability and usability of the model were identified during the early stages of the development process.

Firstly, observations from throughout the development process suggest that tertiary learning spaces in New Zealand can be very innovative, contemporary, future-oriented spaces displaying many of the educational features listed in Table 1. This is particularly notable in the tertiary sector, which has long been considered the bastion of the very traditional ‘chalk and talk’ lecture format. Complex relationships and challenges are arising out of these pedagogical developments and innovations, seemingly supporting the need for this tool to a) aid researchers in these settings to act with ethical praxis and understanding, as well as b) help formal ethics review committees and bodies to relate to pedagogical research in these settings.

Secondly, the development process has raised some questions regarding the applicability and usefulness of the base model in its current form:

Will the model be able to adequately prompt and generate thinking and reflections about the affective nature or climate of the learning space? In the exploration of the ethical systems at play with a similar group of people, ‘communities of makers’, researchers found that what they needed to uncover was the often-unwritten climate of the community (Toombs, 2015; Toombs, Bardswell, & Bardswell, 2014; Toombs, Bardswell, & Bardswell, 2015). These researchers undertaking long-term participant observation of ethical systems in maker communities were able to consider what sort of space is it? – is it characterised by overt-caring, covert-caring, mentoring, helping, adhocism, empowerment, judgement, identity expression, level of engagement, and acceptance of failure? These sorts of intangible or ‘soft’ features have been historically difficult to measure or observe (Buissink-Smith, Mann, & Shephard, 2011), and it remains untested whether the base model as proposed here will be able to uncover this depth of understanding.

Early discussions indicate that it will perhaps be the nature and strength of the relationships between all of the actors involved in the (wider) pedagogical community that will be the most important factor in understanding the ethical systems at play. Although related to the point above, in development thus far, the model has been able to cope with graphically representing these relationships with line variation between the actors (e.g. thick lines, thin lines, bold lines, dotted lines, two-way lines, one-way lines).

In terms of the applicability of the model, questions have been raised as to whether it could be usefully applied to pedagogical research in contexts such as a) old-style, outsider-in research on new learning spaces, b) new-style, insider research in relatively traditional learning spaces (sometimes ‘chalk and talk’ methods are still used and considered to be appropriate due to class size, content or space issues), c) quantitative-driven learning analytics, big data mining, and d) learning spaces that involve little face-to-face interaction (e.g. distance courses, MOOCs).

These observations and questions have arisen out of a development process that has been limited to informal discussions, workshops and often anecdotal or experience-based observations. Despite its exploratory nature, this development process offers some insight into furthering our understanding of the ethical systems at play in future-oriented learning spaces. Further research is now needed to test the applicability and usefulness of the base model.

The authors are embarking upon (ethically-approved) formal research into the application of the developed base model, with a focus on the following questions:

1. What is actually happening in contemporary learning spaces and in pedagogical research?

a. Can a pattern of language be

developed, or rules of engagement?

b. What under-explored or

unexplored ethical issues are arising?

2. Is this model a useful tool for exploring the ethical systems at play in these spaces?

3. What are the implications for pedagogical research(ers) and formal ethical review bodies?

A key purpose of this paper has been to provide an overview of the development of a model for exploring the ethical systems at play in future-oriented learning spaces. The development process has raised some interesting questions that can usefully be tested in future research with the intention that the model will contribute to empowering those involved in pedagogical research, as well as informing the continuous improvement of formal ethics review processes, and generating positive experiences of ‘getting ethics’.