Inga Heyman, Gavin Innes and Kate Goodhand, Robert Gordon University, UK

In response to failings to protect those most vulnerable in society, multi-agency public protection practice has received significant media and government scrutiny (Braye, Orr, & Preston-Shoot, 2011).

Public protection legislation directs core agencies such as police, education, health, social care and fire and rescue services, to co-operate and work together. Governmental direction sets out key shared safeguarding responsibilities and arrangements for individuals, professional groups and teams (Scottish Government, 2010; HM Government, 2015). However, difficulties remain between organisations to understand each other’s priorities and responsibilities (Dickinson & Glasby, 2010). Despite an appreciation of resource and outcome benefits to collaborative practice, integration of safeguarding public protection policy into practice and education is often challenging (Datta & Hart, 2008). Difficulties at an organisational level can transpose at an individual level where entrenched professional beliefs and divisions can compromise partnership working and joint safeguarding.

Nonetheless, through a focus on protection policy development and, to some extent, practice research (Campbell, 2014; Dickinson 2008) it is clear public protection has indeed been greatly improved over the past 10 years in police, health and social care practice to support a higher level of recognition, knowledge and skills. Focused training relating to ‘individual at risk’ groups receives mandatory status within some higher education sectors and for those in operational practice (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2013).

Many health and social care curricula invest in inter-professional education to encourage exploration of information sharing, reporting and case management. Yet, multi-agency public protection education has received little attention in higher education and practice settings. Additionally, uni-professional and inter-professional education tends to focus on single silos of harm, for example child protection or domestic abuse (Sinclair, Camps, & Bibi, 2012; Tufts, Clements, & Karlowicz, 2009) and this is often explored within in-patient settings, seldom incorporating the breadth of professions found in everyday community based public protection working. It would be unusual for example to witness police, fire and rescue services, general practitioners and health and social care providers coming together to better understand multi-agency responses.

Furthermore, there is little evidence of multi-agency educational opportunities considering the complexities of public protection practice when there is more than one, multifaceted safeguarding issue within a family group or community, as is frequently reflected in day to day law enforcement, and health and social care interventions. It could be argued that, despite the obvious benefits of improved understanding of risk factors and response to discrete areas of harm, there is potential that practitioners may fail to recognise overlapping multi-generational issues.

A lack of advancement in addressing the complexities of multi-agency education challenges us to adequately understand professional values, identities, beliefs, priorities, cultures, underpinning professional theoretical models, legislative interpretation and expectations of professional groups which influence joint working. Therefore, despite legislative drive and policy development to improve safeguarding, there remains a glaring gap in broader multi-agency collaborative learning.

This paper discusses the development, application and future possibilities for innovation of a unique educational tool to address this gap in multi-agency education which aims to support understanding of key public protection issues in Scotland. It encourages learners to recognise risk, explore overlapping and ‘grey areas’ of harm and understand partner agency best practice and response whilst encouraging cross-sector working, appreciation and support. Through gaining insight into other agencies’ safeguarding roles the learner has the opportunity to gain a deeper insight and broader perspective of the complexities of interventions beyond their own discipline whilst recognising opportunities for joint resource management.

The Collaborative Outcomes Learning Tool (COLT) was initiated by Aberdeen City Division of Police Scotland. It brought together higher education and partner organisations involved in contemporary safeguarding roles to advance an educational resource to promote joint working in multi-dimensional public protection issues. Each partner in this innovation brought a level of expertise and understanding mirroring the desired co-operation and skills valued in cross sector working in public protection practice. This was enhanced by established strong relationships of trust and a history of working together and across boundaries. Some team members had worked in both the police, health and higher education bringing insight into the priorities and conflicting demands of each organisation from an ‘insiders’ perspective. The funding body, Police Scotland, shared a vision of utilising the resource in their own learning environments but also sharing the tool with partner agencies to encourage the deeper cross organisational understandings required to promote balanced information sharing, protection and resource allocation.

The e-learning package created was an online tool with a set of matching DVDs to allow use in different modes of delivery: online, classroom or blended learning (Garrison & Vaughan, 2008). The tool incorporates a number of filmed scenarios based on a fictional Scottish family, with video clips of characters answering key questions to camera, professionals (e.g. Social Worker, Police Officer and General Practitioner) providing their expertise in consideration of joint working, specific expertise or operational best practice response. Individual learners may work through the content online or in the classroom environment with the opportunity in either setting to select discrete safeguarding issues or view the complexities of multi-risk, multi-generational harms in one family group.

The structure allows the learner firstly to be familiarised to the family group around which the tool is centred in an innocuous situation; organising a take away meal for dinner. Some tensions within the family are apparent but not made overt with an aim to draw the learner into the storyline. The five scenarios within the resource span child sexual exploitation, adult support and protection, mental health and substance use, radicalisation and gender-based violence. Each clip has been crafted to reflect contemporary challenges in practice where inter-agency tensions are often apparent.

Meeting the characters. Not all is obvious to the learner at first mirroring the reality of potential hidden harm

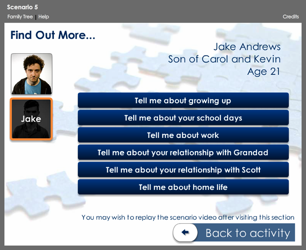

The learner can interact with the character to encourage investigation and question what elements influence their behaviours and to understand the family relationships. By clicking on pre-set questions the learner can gain insight into childhood experiences and influences, strengths, resilience and vulnerabilities. In a similar way they can also ascertain the opinions of various experts that work in the community from operational police officers to fire personnel. This encourages ‘modelling’ (Bandura, 1977) as learners mirror questioning and advice seeking behaviours required in practice areas to support assessment and development of this new knowledge, skills and attitudes desired in collaborative working.

Engaging with and learning from practice experts

The rationale for the structure of the tool is supported by ‘andragogy’, “the art and science of helping adults learn" (Knowles, 1980, p. 43). In particular adults must understand the relevance of the topic presented, be able to draw upon their own experiences and then want to apply their new knowledge to problem solving. In conjunction with this an adult needs to have responsibility for their own learning, be ready to assume new roles and be motivated internally. Individuals are assumed to learn better when they control the pace of learning and when they discover things by themselves (Leidner & Jarvenpaa, 1995). Using the COLT resource the learner can control his or her own learning through setting the pace and direction of their engagement.

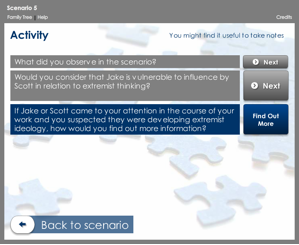

Pacing and guiding learning

The tool has not been designed to provide a ‘right’ answer or suggest there is only one course of action. Instead by the use of video and layered or staggered pieces of information the aim is that the learner ‘constructs’ internal representations of knowledge to formulate their own distinct version (Tsay, Morgan, & Quick, 2000). For ‘constructivists’ more prominence is given to the engagement of students in the learning process than on finding a definitive answer, useful in complex and emotive situations such as occurs in the topics presented. For learning to occur it is purported that interactive activities motivate learning more effectively than passive ones. Brandt (1997) suggests that web-based education, including the use of video, can assist this process by engaging learners.

The use of videos as ‘triggers’ to learning is not new and has been explored in nurse education by Nichols (1994). Video triggers have also been used to assess nursing students’ communication and knowledge (Crawford et al, 2009). In the COLT the ‘trigger film’ acts as a stimulus for debate and discussion of complex issues involving aspects of professionalism. Nichols upholds this as particularly useful for learning in the affective domain of Bloom’s taxonomy (Baud & Pearson, 1979).

The interactive nature of the tool through its use of videos and ‘question and answer’ format allows the learner to engage in realistic simulated scenarios without risk to themselves or others (Ward, 1992). As with all simulation the ‘real’ learning takes place in the ‘debrief’ and feedback session (Issenberg, McGaghie, Petrusa, Gordon, & Scalese, 2005). The ‘feedback’ the learner can expect to receive is delivered by the ‘voice’ of the expert professional and in a class-based situation also from their peers and facilitator(s). This is a crucial time when reflection can consolidate new learning and attitudes (Boud, Keogh, & Walker, 1985).

Filmed by Education Media Services (EMS), the drama scenes were recorded on location at a property in Aberdeen city centre, while the face-to-camera footage was recorded in a studio on campus. Filming took place in a relaxed atmosphere, using a conversational style to provide the learners with a sense of the characters talking directly with them. Informed by digital storytelling there is an opportunity for the characters hidden personal stories to be discovered through digital media. Using conversational production (Lambert, 2006) the learner has the choice to select short film formats to seek out improved understandings specific to each character. Individual histories and inner thoughts are disclosed as well as insight into family relationship challenges and resilience. If the learner does not select these filmed clips the full story is not apparent making it more challenging to understand family dynamics and risk. Through this process an opportunity is made available to connect the learner more deeply with the characters to ‘bring them alive’ thus encouraging deeper immersion and opportunities for learning.

Opportunities to engage with characters, discovering relationships, inner thoughts and hidden histories

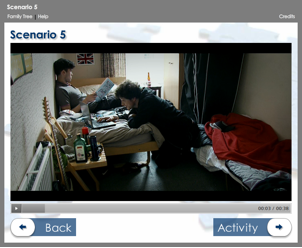

The clips featuring actors have been deliberately un-sanitised to support reality of operational settings and contain swearing, jargon and local dialect. Discussions with operational officers and health and social care practitioners in the production planning phase suggested that such un-sanitation reflects realism and ‘truth’ of situations in real life practice thus encouraging learner insight and engagement. In addition, Police Scotland supported the authenticity of the tool through release of two operational officers to appear as response officers to an incident of domestic abuse within the family home. Two hundred video clips were recorded for the project. In addition, 360 degree photographs were taken of the interior of the property to be stitched together as an interactive virtual tour to provide learners with an opportunity to have a ‘birds-eye’ and close-up view of the family home to encourage immersion and familiarity of the incident settings. The purpose is to develop an exciting, constructive and challenging learning environment to support student enthusiasm for learning (Jensen, Adams, & Strickland, 2014).

‘Trigger film’ acts as a stimulus for debate and discussion of complex issues

The school e-Learning Adviser designed a platform for the video clips to be embedded which would include functionality to access the clips of the characters answering questions, clips of professional opinions, interactive questions and further reading to engage and inform the participants (Glen & Moule, 2006). Once the scenario template was agreed, the 200 video clips were divided up and inserted into one of the five scenarios.

Since the e-learning content was created specifically for the Police, it was designed to meet their IT requirements. This raised some challenges with the Police IT system being very strict on the functionality available to officers. For example, officers use an old version of Internet Explorer with JavaScript, Cookies and steaming video unavailable. Functionality would therefore be limited within the Flash Media (self-contained e-Learning package). Videos would therefore need to be present within the Flash Media and not streamed from a separate dedicated server. With videos in the Flash Media the download and online course appears slow. The insertion of onscreen text to say “Loading…” was included to encourage the user to be patient.

To support ease of access for other organisations the resource has been hosted by With Scotland. This national resource connects a range of services to research, resources and practice, knowledge exchange and ideas across child and adult protection communities and other networks.

The video clips were filmed in high definition (HD) by a professional film crew so we were keen to retain the original production quality but without access to a video server. The solution was to give two download options to the end user: High Quality Video and Lower Quality Video. So, depending on the speed of the internet access, the user can select the original high quality videos or the faster lower quality videos.

COLT has been utilised in multi-agency, inter-professionals and uni-professional learning within undergraduate and postgraduate settings. Flexibility of application has allowed educators to ‘cherry pick’ discreet public protection issues or a total package to aid simulation of multi-agency case planning in inter-professional education. In a supported environment there are opportunities to explore and practice collaborative interagency information sharing, risk assessment, intervention planning, collective decision making and consider barriers and facilitators to collaborative working in contemporary practice whilst keeping the individuals and family needs foremost. In this context the resource provides a platform to develop an improved understanding of competing priorities and challenges of resource allocation faced by other agencies which may impact on collaborative working. Through working together on a multifaceted public protection case, learners can consider what other disciplines partnership working and initially view in a situation through a different lens and to seek out collaboration to support a ‘bigger picture’.

With a commendation award in the finals of the British Universities Film & Video Council, Learning on Screen Awards 2015, the project team have reflected on the facilitators to success and future development of COLT. Using cutting edge e-learning software with well-established development techniques, the real innovation within the project is found around multi-agency teamwork and learning outcomes focused on collaboration, not just as an outcome of learning but as a result of shared resource development.

In addition, professional film production creates an engaging narrative as a foundation for student immersion. This teaching resource approach is now being developed in other areas where complex decision making and multi-professional understanding is crucial such as contemporary multi-agency responses to radicalisation. Through pushing the boundaries of collaboration beyond operational working into education there are multiple opportunities to develop this type of learning in other contexts. For example, this may lie in other environments out with healthcare where multi-professional, collaborative responses are crucial, such as safety and emergency response within the off-shore energy sector or disaster management, bringing new prospects to joint, flexible learning.

Following the same theoretical principals, COLT itself is to be developed further with two of the current characters extending their stories into a new national resource focused solely on multi-agency identification and response to those at risk of radicalisation. There are also considerations of developing an extension to COLT allowing the learner to branch in two ways to view firstly family outcomes if no multi-agency support and protection is put in place, and secondly potential outcomes if identification and joint working is enacted to support reduction of risk and arrest possible generational harm.

Customary student feedback from both uni- and multi-professional sessions has been sought to continuously evaluate student experiences and learning. These informal reflections have been extremely positive. However, formal evaluation of the resource is now required to provide a clearer understanding of the resource value. Understanding the impact of such learning in public protection practice is fundamental to the further development and application of this tool. Research opportunities also lie in understanding the educators experience in using COLT as well as the practicalities of facilitating multiagency education in times of financial austerity and competing curriculum priorities. With access to the resource recently made widely available to multiple organisations there is a strong desire to collaborate with practice partners to evaluate how the resource is being utilised in learning and in what contexts.

The production and application of COLT reflects a true collaboration between higher education, law enforcement and those professionals involved in public protection mirroring a willingness and desire to work together. Through connecting resources, both financial and professional, it attempts to draw out and reflect on cultural and professional differences in safe guarding practice. COLT seeks to promote dialogue that begins to bridge the fissure of separatist working and variable multi-agency understandings of the complexities of vulnerabilities, risk and harm.