Lynn Boyle and Dianne Mitchell, University of Dundee

This on the horizon paper discusses the early stages of a review of the programme core reading list for the BA Childhood Practice degree, which is delivered at a distance, online at the University of Dundee. The existing reading list has been augmented and supplemented over time since the programme was validated, however the list has not been systematically reviewed since it was first drawn up. Recently the University has introduced a reading list management software system (TALIS) which has enabled the researchers to reconsider the core programme reading list and to have training on the use of the software. Books, articles and journals as well as online resources can now be easily added to the reading list. This unifying approach led to the realisation that the core programme reading list has been somewhat overlooked and is not fit for the purpose of giving students the most pedagogically appropriate suggested reading.

Programme or module reading lists are as much a part of a university programme of study as the lectures and the content of the learning materials. Every programme of study will have one, possibly more, reading lists, particularly if these lists are issued on an individual module basis. The purpose of the programme reading list is to identify essential and appropriate books and to guide students as a starting point to their own literature searches. The University of Dundee’s guidance on Reading and Resource Lists (2013/14, np) states that one of the key aims of the reading list is to:

“enhance the student learning experience through effective consideration and timely communication of the details of relevant books and resources to support student learning.”

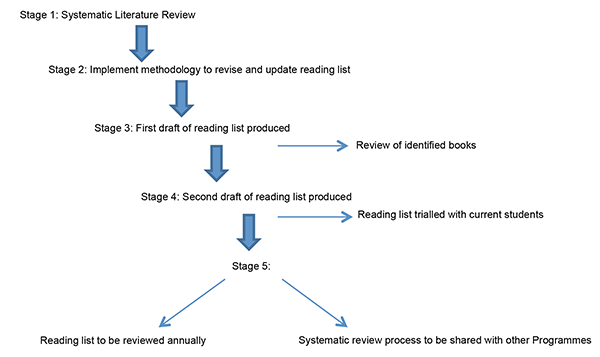

The proposed research will reflect and report on the process of systematically reviewing a core programme reading list. This will lead to the creation of a core programme reading list which is fit for purpose and is produced with students as co-creators. The research stages are shown in Figure 1.

The rationale for auditing and systematically reviewing the reading list is to ensure that the list is current and reflects the range of backgrounds and working contexts of the students (for example, early years settings and after-school clubs). The list will contain, predominantly, books which are available online to reflect the programme’s situation as a primarily online distance learning programme with an increasing number of overseas students. The reading list has been suggested as a pedagogical tool (Siddal & Rose, 2014) yet it remains under developed and largely overlooked by academics.

Figure 1: Flowchart showing study stages

A systematic literature search to identify existing academic papers on reviewing or constructing academic programme reading lists was carried out with the following keywords used:

|

Key

term |

AND |

OR |

|

Book list |

Creat* |

Writ* |

|

Course literature list |

Creat* |

Writ* |

|

Reading list |

Creat* |

Writ* |

|

Literature list |

Creat* |

Writ* |

The limiters for the search were that keywords were to be found only in the abstract, the article was to be written in the English language and that it was to have been published since 1 January 2002.

A total of four databases were searched, ProQuest©; ASSIA, British Education Index and Web of Science, with the key search terms being combined in the Web of Science search. The searches in ASSIA and British Education Index returned some possible relevant articles, (15 scholarly articles in ASSIA; over 500 in British Education Index), however when the abstracts were read many articles were regarding creativity or book lists such as novels suitable for primary school classes to read. The combined search in Web of Science gave a possible 25 articles of which one paper, Stokes and Martin (2008), was considered to be of relevance as it addressed the topic of reading lists directly. The ProQuest© search identified a total of 31 articles, of which one was considered of relevance. As there were so few articles, a further keyword search was undertaken in ProQuest© with reading list AND creat* OR writ* with the earlier limiters. This search gave over 100 articles, of which two were felt to be of relevance as they contained some reference to reading lists. The three articles from the ProQuest© search were Atkinson, Matusevich, & Huber, (2009), Weick (2003) and Zimmerman (2009). These articles all addressed the topic of higher education programme reading lists in some level of detail. A Library colleague also passed an article to the team which discussed reading lists in the context of an English university, (Atkinson, Conway, & Taylorson, 2010), and this was added to the literature search results.

The search identified that there is minimal literature existing which explores and evaluates the value and merit of what could be considered an excellent programme reading list. It has been suggested that there is an assumption that there is little value in research regarding this ‘unproblematic feature of teaching and learning (Piscioneri & Hlavac, 2012, p. 425). Conversely Stokes and Martin’s (2008) research focuses on student perception and expectation of the reading list alongside the behaviours of lecturers in relation to the students’ use of the list. The work does not consider the processes, creation and co-creation of the list, influenced by student participation and team collaboration. The academic reading list is viewed as apparent or practically created by osmosis by a group of academics who are expert in their own fields, however early evidence suggests it is a random process and core lists are dusted off each year with a couple of new books added which have been selected through staff purchase or pushed from academic publishers (Swain, 2006). A lack of appreciation of the importance and value of the reading list may also prevent the systematic approach which would normally be given to a literature search for research purposes.

The process of reviewing the reading list will consist of an Action Enquiry project (Lewin, 1946). This method will ensure rigour in the process (Pine, 2009). In our data gathering we will ensure the triangulation of data (Denzin, 2011). This will be achieved by gathering the information to collate the new list from a number of sources including current students, staff, current library stock, publishers, other institutions and a full audit of the books on the current list. This method is essential to ensure rigour in the creation of future reading lists.

In considering an action research method we will aim to produce a replicable learning cycle where the core reading list will be reviewed using the same methods in each subsequent academic year. This aim of improving practice is embedded in action research project and is appropriate for the ethos of this journal (O’Leary, 2014).

The fluidity of action research (Daniels & Squires, 2014) will enable the researchers to alter the nature of the research design, if necessary, as the project unfolds and to reflect on the process, to make amendments for future systematic reading list review.

The researchers plan to have a systematic approach to review the core programme reading list for the online BA in Childhood Practice. The proposed data collection methods are presented as a concept map in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Concept Map of Proposed Data Collection

By considering each of these areas, the researchers plan on ensuring the list is fit for purpose, has the most current and appropriate reading for the entire cohort of students and can be easily accessed by all students and the staff team.

The research carried out will inform the review process and will initiate the selection of books for the new core programme reading list in readiness for the new academic session. This will draw on the recommendations of the staff team and also from the feedback received from students via the online questionnaire.

The current books on the programme individual module reading lists have been collated to demonstrate the parity of the reading across the programme and to consider how these fit with the ‘core programme’ reading list. There has, for the first time, been a systemic search for existing and new literature on the subject of Childhood Practice from the library and from publishers who have been invited to recommend suitable books as well as staff team members investigating the range and availability of books. A key feature of the books was that they would ideally be available for the University library to purchase as e-books, thereby ensuring that the core reading list would be available to all students both in Scotland and further afield. These books are in the process of being reviewed individually and categorized in areas of content.

An initial questionnaire will be issued to the existing cohort of 150 students to invite views on the current core programme reading list. Students will be asked questions themed around purchase, reading, value and opinion. The rationale for this is to validate the reading list by asking current student opinion on their use of the list and the values they place on the use of the list. This data will then be analysed and used to inform the staff team of the validity of the current list and to inform change. This is with an aim of ensuring that students are co-creators of the list. A thematic method of analysis will be used to review the data collected from the questionnaire and will be used to influence the books to be included in the new reading list. To develop the concept of students as co-creators, the students will also be asked a question on the reading list as part of every subsequent module evaluation

There will also be a systematic review of available appropriate books by the academic team. This will include:

The draft reading list will be produced. Once all of the data has been collected the researchers will analyse the questionnaire and collate all of the suggested books from the team, the publishers and from the students. The analysis of the questionnaire results will influence if the books included on the current core reading list will be used in the following academic year. This will be dependent on the views of the students in their opinion of the value of the text to their studies. The same books identified by the students will be reviewed with the staff team and the approved books will be included in creating a draft core reading list.

The books received from the academic publishers will be reviewed by individual team members who will propose two books which they believe are most relevant and appropriate under each subject topic, for example Birth to 3 years; study skills. The existing books within the library will be collated under the same subject topics and again the process of review will be carried out by the staff team. These will be added to the draft reading list.

Once the draft reading list has been produced the researchers will check to ensure where possible the books are available as e–readers as this allows students from the global community to have easy access to all of the materials. It will also ensure that students are not relying on book purchase at a time when they may be least able to afford this expenditure. The list will be checked to ensure all the current editions of each book are being used and then a final filter will be applied to ensure the core reading list contains the range of topics needed and the list is succinct.

The final draft of the list will be distributed to the wider staff team for consultation and then published using the University reading list TALIS. This reading list will then be trialled for a year with the students

The review will be completed from Stage one again and then the process will be shared with other programmes within the University.

The proposed research project, discussed in this On the Horizon paper, will be enhanced by feedback from the academic community and this is welcomed via the accompanying blog at https://dustingoffthereadinglist.wordpress.com.