Sarah Cornelius and Sandra Nicol, University of Aberdeen, UK

There is substantial literature on PhD supervision (e.g. McCallin & Nayar, 2012; Halse, 2011), but Masters supervision has been under-researched (Ginn, 2014; Anderson, Day, & McLaughlin, 2006. Ginn (2014) has argued that attention should be paid to Masters supervision in the face of the increasing neoliberalization of Universities, particularly to aspects such as instrumentality, ethics and care. This paper also argues for closer examination of the needs and expectations of Masters supervisors in the light of the diversity of students and projects encountered. The focus is on Masters students who are studying part time, often at a distance or through blended learning, and concurrently employed in a professional context. These students are typical of those studying in education and related areas, and also found on management, law or health related courses. The framework underpinning our research comes from theories of adult and professional learning (e.g. Knowles, Elwood, & Swanson, 2011; Lave & Wenger, 1991) which place the learner as an experienced, problem-focused, internally motivated and self-directed individual, within a connected social setting.

Many Masters students being supervised during independent dissertation or project work share characteristics with PhD students. For example they may be self-funded, part time and in employment. Challenges for students and supervisors may also be similar, particularly in relation to cultural differences and expectations, and the focus on a lengthy, often one-to-one, student-supervisor relationship. However, there are a number of factors that distinguish the Masters setting. These emerge from both sides of the relationship. From the student side they are focused on the need for concurrent professional activity. On the supervisor side, assumptions about Masters supervision, prior supervisory experiences and tensions between different supervisory roles are important factors. Some of the issues for students and supervisors are considered below.

Masters students in professional contexts are often self-funded and, despite combining work and part-time study, may face financial pressures. Occupational or government funded schemes exist for students from certain nations or professions, but in the UK, for example, funding opportunities are limited. In the Scottish school sector, Donaldson’s (2010) recommendations led to initiatives which promoted and supported Masters study for teachers, but these schemes are necessarily selective and time limited. Those funding Masters students may have specific expectations or requirements and individual students (including self-funders) may be motivated by promises of career advancement or salary increments. Current trends towards marketisation of education, which place students as ‘consumers’, also have an impact on their expectations of choice and service from supervisors.

Flexible study modes (e.g. part time, distance, blended, online) make study possible alongside professional commitments and support students studying from any location. This flexibility may also mean that supervision occurs outside normal office hours and at a distance. If a student is studying part time, their engagement with the university may extend over a period of several years, which, in turn, increases the possibility that they will change their job or place of residence during their studies. Movement of students within and between countries is frequently observed and there may be considerable cultural and geographical diversity within a cohort. There is a need for issues of diversity and change to be accommodated and students may need support to reframe and redefine research plans to accommodate challenges as they arise.

Unlike PhD students, who can be part of a close-knit research team working on related topics, or a lone scholar, Masters students may be part of a cohort of learners with a range of disciplinary and professional backgrounds. Ginn (2014) reported that an MSc Environment, Culture and Society included students with previous degrees in geography, literature, anthropology and ecology. In our own School of Education MEd programmes bring together students from primary, secondary and post-compulsory education contexts, along with those in related areas. Although an individual student may undertake Masters study to provide them with advanced training in a specialist area, they may find themselves part of a diverse learning community. This diversity means that the prior knowledge that individuals bring to their research projects cannot be easily predicted and supervisors cannot assume this is similar across a cohort.

In contrast to PhD research, Masters study is often undertaken to enhance skills and employability (Ginn, 2014) rather than as a step to further research. Thus, the emphasis during independent Masters project work may be on the development of research skills that equip students with “competences necessary in their future career” (Sin, 2012, p. 293). Ginn (2014) argues that the role of the supervisor is to help students “carve out a space in their Masters protected from a forward-looking post-qualification perspective to enable them to experience ‘being like a researcher’” rather than present the degree as a “means to an end” (p. 112). However, where students are also employees the link between research and profession needs to be explicit and explored. When they begin their studies the supervisor needs to help students “reiterate and refresh [their] position within the whole research context” (Maunder, Gordon-Finlayson, Callaghan, and Roberts, 2012, p. 31). There may be a need for them to critique and problematize their professional context by exploring taken-for-granted assumptions. There are also specific tensions that the supervisor may have to help the student navigate – for example issues around being an ‘insider researcher’ and important ethical issues around actions, participation, consent, reporting and dissemination. Maunder et al. (2012) propose support strategies including group supervision and peer learning and suggest that supervisors should be experienced in the methods they support, mentor students and encourage reflexivity. These recommendations are helpful, but some may be difficult to implement. For example, although positive outcomes from group supervision have been reported (Samara, 2006), there are challenges in bringing together dispersed and diverse learners and supervisors need appropriate training to support collective supervision processes (Nordentoft, Thomsen, & Wichmann-Hansen, 2013).

In all pedagogic relationships educators need to guard against making assumptions about students: the supervisory relationship is no exception. Grant and Graham (1994) noted that supervisors often assumed that students were independent and self-motivated, when in reality exposure to years of “disempowering pedagogical processes” (p. 79) may have hampered this. Empowering students within the supervisory relationship may prevent difficulties arising since these are often caused by a lack of clarity over mutual expectations and responsibilities. It is suggested by Grant and Graham (1994) that students and supervisors should discuss dissertation guidelines to encourage good communication and the building of relationships on the basis of mutual respect. John Jones, in an afterword to Grant and Graham (1994), considered that this offered an opportunity to interrupt the power relationship which otherwise places the supervisor as expert and the student as apprentice. Grant and Graham empowered their students to discuss guidelines within workshops and a support group. Issuing supervisors with their own copies of guidelines allowed issues to be raised in supervisory meetings. However, there was evidence that not all supervisors were keen to engage, thus unequal power relationships were perpetuated.

Graduate supervision as a master/apprentice relationship is a common approach (Manathunga & Goozee, 2007, p. 309), but can be an “unequal power-filled pedagogical relationship” (Grant & Graham, 1999, p. 77). The balance of power may shift over the duration of the relationship (Anderson et al., 2006). Equal and active participation in the relationship can be affected by students and supervisors ‘talking past’ each other or ascribing different meanings to actions, and there can be abuses of power. The supervision relationship is also time limited: developing from apprentice to master takes time, which can be given in a PhD context, but is more difficult within the duration of most Masters dissertation courses.

Being apprenticed to an individual supervisor could limit the opportunity for students to benefit from other perspectives, engage in the wider research community or develop a more broadly informed stance. To help overcome this Maunder et al. (2012) argue for Masters supervision to be seen as an apprenticeship relationship within Lave and Wenger’s (1991) community of practice framework. However, some difficulties emerge when viewing a group of diverse and dispersed Masters students through a community of practice lens. For instance, the common domain, a key ‘dimension’ of a community of practice (Wenger, White, & Smith, 2009), is difficult to identify. Whilst there is undoubtedly a shared interest in the practice of academic research, for many participants this will remain a lower priority than their commitment to their professional context. Student interest in academic research can be short term and strategic – to achieve a qualification – rather than to make an enduring impact on everyday practice. In addition, a shared interest alone “does not necessarily yield a community of practice” (Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002, p. 44) and the combination of distinguishing features (domain, community and practice) is important. Communities of practice may evolve and end organically (Wenger et al., 2002), but groups of Masters students are brought together purposefully and strategically and have fixed end points, after which students may be abruptly removed from university systems.

Within most Higher Education institutions Masters students outnumber PhD students so more supervisors are needed. Whilst PhD supervisors may have to have obtained a PhD themselves, Masters supervision is often an expected part of the portfolio of academic staff. Thus, a greater diversity in supervisors is also part of the landscape of Masters supervision. Supervisors’ practice is influenced by their own experiences of being supervised (Ginn, 2014). Professional development opportunities may be limited as it is commonly assumed that once they have experienced the process as students themselves, supervisors become “automatically always/already effective” (Manathunga & Goozee, 2007, p. 310). Since most supervisors have limited personal experience as supervisees, the supervisor role to which they were exposed may be replicated. They may also have insecurities and a lack of clarity about the role. Even for an experienced lecturer there may be anxieties as expertise may be assumed by others.

One specific aspect of supervision which creates anxieties is assessment. Whilst summative assessment of a PhD thesis is generally undertaken by external examiners and independent internal examiners, a Masters dissertation is commonly assessed by the supervisor. Although other markers may be involved to verify grades, this creates a unique tension for the supervisor who has to fulfil potentially conflicting ‘shaping’ and ‘supporting’ roles (Anderson et al., 2006). The shaping or ‘aligning’ element of the role requires supervisors to act as gatekeepers of academic standards. They shape research ideas, ensure that practice accords with academic and research community expectations and help ensure final products align with academic guidelines. The support or guidance element needs commitment from supervisors to motivate students and help develop their personal agency, autonomy and confidence. As noted above, students need to problematise their professional context and reassess it with an analytical and critical eye. This raises issues about students’ professional identity (Anderson et al., 2006), which may need to be explored during supervision. Supervisors also need sensitivity to power issues that may remain intractable whilst they undertake the dual roles of supporter and gatekeeper of academic standards and assessment.

The discussion above has outlined some of the issues and challenges of Masters supervision and supports the need for further investigation. Masters supervision where students are in professional settings is different from PhD supervision in terms of the nature of the relationship, the diversity of students and supervisors, the role(s) of the supervisor, and the links needed between research and practice. Assumptions are often made about supervisors’ preparedness for the role and point to a gap in our understanding of supervisors’ needs and concerns. This research hopes to contribute to improving our understanding of supervisors’ needs within the context of education and related areas.

In the School of Education at the University of Aberdeen over 30 students progress to a Masters Work Based Project and Dissertation course annually. They represent a variety of programmes of study, ranging from a general Masters in Education, to specialist qualifications for Leadership, Inclusion, Guidance and Counselling. They may represent any sector of education or they may be located in related areas, such as the health or business sectors. The majority of students study part time and partially or completely online.

Students produce three key outputs during the Work Based Project and Dissertation course, and the role of the supervisor in relation to these is outlined below:

1. An ‘initial thoughts’ document. This articulates a rationale for the proposed project, gives evidence of engagement with appropriate literature and suggests initial research or development questions. Along with a brief CV, this is shared with potential supervisors who then volunteer to supervise projects that align with their interests or expertise.

2. A full research plan and ethics application. The supervisor will support the student to plan their work in detail and assess the plan with a second marker to ensure that it is practicable, achievable and aligned with expected standards. Detailed formative feedback is provided. The student cannot embark on data collection until this plan has been approved.

3. A final report. This substantive piece of work (15,000-18,000 words) is normally submitted after about 18 months of independent research undertaken with guidance from the supervisor. The report is assessed by the supervisor and a second marker.

In addition to their supervisor’s support, students have access to online resources, discussion forums, and face-to-face and online group workshops. These have been designed with the aspiration that students should be contributors to a wider community of developing researchers. To support this aim some materials (for example recommended readings) are provided in wikis or blogs to which students can add comments or suggestions. The framework for the course draws from both the apprenticeship and community models outlined above. The student–supervisor relationship remains at the heart of the student experience, but the aim is that both parties should feel part of a wider research community.

The number of students on the course has grown in recent years, and so too has the community of supervisors. Initially a small group (mainly Programme Directors), the team now includes colleagues relatively new to postgraduate supervision and some who do not teach on postgraduate programmes. The issue of supporting the supervisors as well as the students has become an area of interest and has led to the question behind the research reported here: How can support be provided for a diverse group of supervisors managing a diverse set of student projects?

This paper draw an action research project (McNiff, 2014) designed to address the question above. Following input from the School Director of Research and ethical approval from the University, data were collected from a log of questions posed by supervisors to the Course Director (Sarah Cornelius) over an academic year, and from a focus group with three experienced supervisors who volunteered to participate. Analysis using qualitative approaches allowed evaluation of existing support strategies, which included online resources for students and supervisors within the institutional virtual learning environment, private online supervisor resources, email guidance and face-to-face supervisor meetings. Focus group participants were invited to reflect on initial findings to provide verification and subsequent reflective dialogue between researchers informed the development of approaches to support supervisors.

Findings are presented below in three sections: 1) questions raised by supervisors, 2) challenges faced by supervisors, and 3) emerging support needs.

Table 1 summarises three main categories of questions: process issues, practical issues and concerns over individual students. These emerged from analysis of the log queries made to the Course Director by supervisors over a full academic year. The majority of questions concerned course processes and procedures and the supervisor role in connection with these. Questions about what to do at different stages of the process were common, from the very beginning through to the final stages of marking and verification. The extended timeframe of a Masters project, and the small number of students that most supervisors engage with at any one time, mean that issues of process are returned to intermittently and reminders needed – occasionally the same supervisor asked the same question more than once. Queries about practical issues may be the result of the intermittent nature of supervision and challenges prioritizing the role, but also due to the diversity of students. The third category of questions focused on concerns about students. These included anxieties over students who had been out of contact for unexpectedly long periods (reflecting difficulties faced sustaining appropriate one-to-one relationships with distant students); requests for assistance to help challenging students fully understand course expectations; and concerns about the quality and submission of final projects.

|

Category

of query |

Examples |

|

Process

issues |

I have a new student, what do I do now? I’ve received a project proposal, what happens next? Do I need to find a second marker for the full project? How do we work together? |

|

Practical

issues |

Where do I send students to find out about …? Where are the online submissions for me to mark? Can I give my student an extension to the submission date? |

|

Concerns

about students |

My student hasn’t been in contact for x months I’m struggling to help my student develop an appropriate writing style – I’m not sure they understand the course expectations I’m worried about the likelihood and quality of the final submission. |

Table 1. Questions from Masters supervisors.

Information about specific challenges faced by supervisors emerged from the log and discussions with the focus group (Table 2). The nature of supervision – a substantive task undertaken in intermittent short bursts of activity – explains some of the challenges identified. Supervisors return to supervision duties as and when required, perhaps once a month over a two-year period. In the midst of busy schedules and multiple other academic, administrative and research demands, it can be a major challenge to remember key information or know where and how to locate resources quickly. Information and materials were provided to students and supervisors via an online space in the institutional virtual learning environment (Blackboard). Whilst explicitly designed to facilitate ease of access to key information, the underpinning structure was not always clear to supervisors, and often changed over the length of time that an individual student was registered on the course, as part of ongoing course development. Supervisors who found materials difficult to locate reported that they became frustrated and this was exacerbated when they had to locate information quickly.

|

Challenge

identified by supervisors |

Examples |

|

Navigating

online resources |

Where do I find…? If I can’t find stuff I get demotivated, and if I’m demotivated I can’t find stuff |

|

Just

in time and (re)learning needs |

I have a meeting with student later today and need to know… I’ve forgotten… |

|

Dealing

with diversity |

My last student wasn’t like this… |

Table 2. Challenges faced by Masters supervisors.

Additional challenges were created by the diversity of students. Supervisors reported that no two experiences of supervision were ever the same, since students bring to their studies their personal learning needs and preferences, along with expectations generated by different programmes of academic study, and experiences from diverse cultural, social and professional backgrounds.

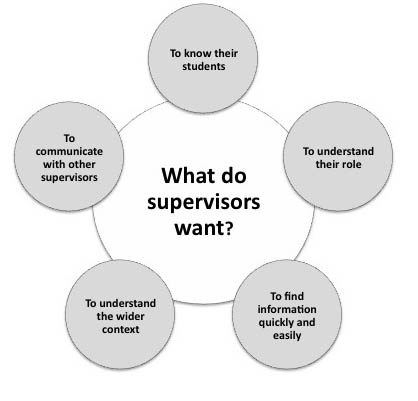

Supervisors’ needs were identified from thematic analysis of focus group discussions and classified into five key areas (see Figure 1). Further details of each of these areas of need are provided in Table 3 and discussed below.

Figure 1. Emerging areas of supervisors’ support needs

|

Supervisor

needs |

Examples |

|

To

know their students |

·

More

information about students -

Their

journey through their prior studies -

Motivation -

Context

and obligations ·

Tools to

help develop relationships (especially online) |

|

To

understand their role |

·

Timeline

with key stages and expectations Guidance on the role

of the supervisor Guidance on online interaction |

|

To

understand the wider context |

An insight into what

-

Masters

teaching is -

Masters

level expectations Programme structures |

|

To

find information quickly and easily |

A timeline with key

stages and expectations and links to resources Reminders, an early

warning system/calendar that triggers action Quick and easy to

find online information, step-by-step directions to online information Personalised, just

in time support |

|

To

communicate with other supervisors |

Conversations with

previous tutors who taught the student Focused, small group

discussions around supervisors’ questions and issues To feel a sense of engagement

and community |

Table 3. Examples of supervisors’ needs.

As well as providing further evidence of the need for ‘just in time’ information and a clear understanding of their role and responsibilities, this analysis reveals additional needs beyond the practical and everyday. Supervisors outlined difficulties involved in getting to know students (particularly where online communication was necessary) and requested more background information about students together with guidance on the use of online tools to facilitate the development of trust and rapport. They expressed a desire to understand the wider context of the dissertation project, including general expectations of Masters level and information about the range of programmes that students study. Specific issues around understanding their role included discussion of tensions between supervision and assessment and the responsibilities of first and second markers. Finally, an interest in communicating with other supervisors to discuss issues and problems, feel part of a wider community and develop a common understanding of the role, also emerged. Supervisors expressed a preference for small group face-to-face discussion around specific processes or problems, rather than online discussion (for example via a blog). They suggested that communicating online might make it difficult to admit to frailties and personal challenges.

The findings presented above provide an insight into supervisors’ questions, challenges and needs. The questions and challenges suggest a number of interrelated themes which warrant further discussion to identify appropriate support strategies. These include prioritizing the supervisory role and establishing and sustaining effective supervisory relationships. Findings also add to evidence from other sources that reveal difficulties for supervisors in managing conflicting pastoral and pedagogical roles. Issues of (dis)engagement and anxiety are an additional overarching theme that requires exploration to ensure that appropriate support strategies are developed. These areas are discussed below with reference to the models of supervision presented earlier and other research in order to make suggestions to help meet the needs of supervisors.

Supervisors are concerned about how they can give supervision the attention it deserves within a context where there are competing pressures on their time. The need to provide appropriate recognition for the role has been noted by Shannon (1995), who suggested that “if there is no workload recognition for the supervisory role, then it may not be done well, or it may be avoided altogether” (p. 12). At the University of Aberdeen supervisors are given recognition for supervision, but as with many other roles, the hours allocated do not always reflect the work undertaken. The current model relies in part on the goodwill and professionalism of supervisors. In a more overt community of practice model supervisors may need to increase their contributions (Maunder et al., 2012). This may be currently unrealistic without more radical re-thinking of expectations and responsibilities.

An open and transparent approach to workload allocation is one important element of raising the visibility and priority of supervisory activity, but methods of attracting supervisors’ attention are also needed. An email newsletter has been tested to alert supervisors to expectations and key actions required at critical points: for example when students are allocated to supervisors or when a final project is submitted. Newsletters include direct links to key documents to allow immediate access and prevent supervisor disengagement. With such an approach a balance has to be struck between merely adding to the supervisor’s email inbox and providing timely and useful information. However, initial feedback suggests that for some supervisors newsletters go some way towards addressing issues of engagement.

“Unequal underpinnings at the level of lived experience” (Grant & Graham, 1994, p. 165) are also relevant to the issue of prioritisation. The undertaking of a Masters level project is likely to be a major commitment for the student. For the supervisor the role is normally one small part of their workload. The inequality of experience that results has the potential to create difficulties in the supervisory relationship. An open discussion of the priority that can be given to supervisory activity could be held with students to avoid such difficulties, whilst an alternative solution would be to reduce the reliance on supervisor as expert so that the student can seek support from a wider community of peers.

Prioritisation and power issues are closely linked and will exist within any framework underlying Masters dissertation courses. Encouraging students to engage with wider communities of researchers and supporters, and providing appropriate support for supervisors may go some way to reducing pressures.

Participants in this study raised issues around the need to establish an effective relationship in the context of limited background information about students and a reliance on online means of communication. Given the widespread recognition that the student–supervisor relationship is key to success (e.g. Grant & Graham, 1999), this is an important issue. The concern with relationships also aligns with Grant’s (2005) observation that a psychological discourse of supervision is “in the ascendant” (p. 350), as this positions the supervisor as a caring, expert professional who provides motivation, guidance and support for the whole student. Whilst guidance on what to discuss with new students often focuses on reaching common understandings and arrangements (e.g. Grant & Graham, 1994), findings above suggest some additional prompts might be helpful to establish effective working relationships. A checklist of questions which encourage sharing of information about prior academic, research and professional experiences, and explore students’ motivation for engaging in research would support the building of a relationship based on shared understanding and mutual respect rather than implied or perceived power structures. It may be helpful for supervisors to share some information about their own research experiences to establish points of connectivity and commonality, along with trust and mutual respect (Nussbaum-Beach & Ritter Hall, 2012). Meaningful reciprocal exchange in the early stages of a relationship may also help to surface issues of cultural, conceptual or disciplinary differences which could otherwise lead to ‘talking past’ and even ‘acting past’ each other later on. Guidance could also include encouragement for students to develop personal support networks and engage with a wider community of researchers to help them appreciate other perspectives and overcome the challenges of a master/apprentice approach.

When student–supervisor communication is entirely online, issues of access, technological confidence and social presence (the ability to project yourself as ‘real’) can complicate the development of relationships. The use of technologies that allow better projection of personal identity (such as web or video conferencing) can be useful in establishing an effective working relationship (Cornelius, Gordon, & Schyma, 2014). These technologies also offer benefits in terms of tools for collaborative working and making recordings, which can be particularly helpful where language differences between student and supervisor exist. Wisker, Robinson & Shacham, (2007) suggest that “interactions at a distance should be able to be at least as robust as many of those conducted face-to-face” (p. 301). Issues of power and control may however endure, for example when institutional tools afford specific privileges to the supervisor. These can be overcome by ensuring all parties are familiar with software or by providing choice over the tools used. Looking beyond an institution’s list of supported technologies to those used within the student’s professional practice may be appropriate.

Working with diverse and distributed Masters dissertation students requires the use of approaches which develop appropriate relationships and foster common understanding through effective communication. Support may be needed to ensure that supervisors are confident with appropriate guidelines and technologies, and the sharing of supervision experiences through discussion may be helpful to identify common issues and explore solutions.

During the focus group perceived conflicts between the pastoral and pedagogical roles of the supervisor were articulated. The need to be simultaneously project sponsor, supporter and assessor was identified as an area of difficulty. Tensions were also highlighted in Anderson et al.’s (2006) study, where it was noted as “problematic to determine in practice where the boundary lay between the supervisor’s responsibility to bring the dissertation to meet academic standards and the students’ responsibility to take their own work forward” (p. 160). The issues of conflicting supervisor roles can be surfaced in initial discussions between student and supervisor. However, further exploration of the impact of being caught between the supervisor as authority in the field and supervisor as authority over the student (Grant & Graham, 1999), is needed to ensure that students and supervisors can be appropriately empowered. Grant (2005) notes a trend towards supervisors not examining theses and attributes this in part to “tensions between the supportive and motivating Psy[chological]-supervisor and the objective examining Trad[itional]-supervisor” (p. 350). This trend has the possibly uncomfortable potential to further empower one supervisor over another, since assessment may be perceived by supervisors as of themselves as well as of their students’ submitted work. Thus, it may simply move power issues from one relationship to another: as Foucault (1998) suggested power is omnipresent and in every relation. Grant also acknowledges that there are risks associated with psychological-supervision “in a context of significant institutional and social differences and limitations” (p. 351). The implication is that there are limitations to this discourse, and these may become more evident as the diversity of students and project formats continue to increase. de Kleijn, Meijer, Brekelmans, & Pilot (2015) suggest that effective supervision requires the ability to adapt support strategies to meet student needs “in terms of explicating standards, quality or consequences, division of responsibilities, providing more/less critical feedback and sympathizing” (p. 117). It is clear that supervisors need to draw on a range of approaches to supervision in an open manner to provide appropriate support. Participation in open dialogue with other supervisors may help achieve this.

Supervisors expressed a tendency to become quickly disengaged from their role if it was not easily fulfilled. If information needed to address an immediate problem was not readily available, they were easily frustrated and demotivated. This created a negative cycle in which demotivation made it more difficult to find information. Supervisors also expressed anxieties about their role and tended to speak of their experiences in a self-deficit manner, often attributing problems to their actions rather than those of their students or other stakeholders.

Supervisor anxieties may stem in part from the independent way in which much supervision is conducted. Supervisors rarely have the opportunity to talk together about their experiences, and the initial focus group revealed the value of such events to encourage reflection and exploration of common challenges. Some of the challenges faced are common across Masters and PhD level supervision, for example developing students’ academic writing skills and working in intercultural contexts. Since the focus group was conducted additional dialogue at a series of workshops open to all supervisors has proved beneficial. The outcome of one workshop was a ‘wishlist’ of issues and additional support needs which will be addressed in the future.

The lack of experience and relatively limited opportunities for situated professional development in this area may also contribute to insecurities and a lack of clarity about the role. Despite this, supervisors continue to volunteer for the role, and note the rewards. These include the professional updating enabled through dialogue with others with different perspectives on shared interests.

Whilst it should be acknowledged that findings presented here draw on the experiences of a small group of Masters supervisors in a particular context, some emerging issues appear worthy of further consideration:

Current frameworks for supervision, particularly the pedagogic and community models, appear to have some limitations in the context of the needs listed above and it may be timely to consider alternatives which draw on the framework proposed in Table 4.

|

Supervisor

needs |

Issues

to consider |

|

To

know their students |

Students

and supervisors need support to: Establish open and reciprocal relationships Ensure common understandings and mutual respect Establish and maintain effective communication. |

|

To

understand their role |

Students

and supervisors need support to: Explore the nature of the supervisory role to manage expectations and highlight areas of challenge and conflict Draw on support from a wider community Ensure a shared understanding of the student role and responsibilities. |

|

To

find supporting information quickly |

Supervisors need targeted,

contextualised, easily accessible and (re)learnable support materials |

|

To

communicate with other supervisors |

Supervisors should have opportunities for

reflective dialogue with other supervisors to encourage sharing of

experiences and approaches, and help them develop confidence and build

competence |

|

To

understand the wider context |

Supervisors value information about the

wider Masters level context, and need to have shared understandings of local

institutional and programme issues (including recognition and role

prioritisation) |

Table 4: Proposed framework for supporting Masters supervisors

Reconceptualisation of the Masters dissertation and the role of the supervisor should also acknowledge other key drivers and directions in relevant professional areas and academic research. Notable amongst these are trends towards open scholarship (Weller, 2011) including free and open sharing of resources and research outputs; and calls for the development of digitally literate connected practitioners, both within professions (e.g. Further Education – Morrison, 2012), and as a route to effective professional development in the digital age (Nussbaum-Beach & Ritter Hall, 2012).

One framework that may be worthy of further consideration as a model for supervision is the network of practice. This is a “loose epistemic network” in which “practice creates a common substrate” (Seely Brown & Duguid, 2001, p. 205). Relationships between members are looser than those in a community of practice, and members may never know or even know of each other: this would reflect the situation faced by distributed Masters students. Whilst networks of practice are regarded as effective for sharing knowledge, they can also demonstrate lower levels of communication than a community of practice (Wenger, 1998). This may result in difficulties in terms of creating effective supporting relationships between supervisors and students and require a rethink of the role of the supervisor. Seely Brown and Duguid (2001) note that the process of communication in a network of practice is one which requires dis-embedding from a local context to the general, and then re-embedding in the recipient’s professional context. In a Masters supervision context it might be argued that the supervisor could have a role in supporting this dis- and re-embedding, acting as a translator between the student’s professional or disciplinary context and the wider community of academic enquiry. An alternative, less formal model may be the ‘virtual community’ (Johnson, 2001). These are designed communities which use current technology, exist to address an identified need or task, are organized around an activity, formed as the need arises and do not need formal boundaries (Johnson, 2001; Squire & Johnson, 2000). It is possible for communities of practice to emerge from virtual communities, perhaps where a group of students with related project interests emerges. This less structured or theorised view avoids some of the pitfalls of more structured frameworks, but still raises questions for supervision, such as:

Further research is necessary to explore the implications of these alternative approaches.

Whilst the research presented here includes suggestions for very pragmatic and practical steps that can be taken to respond to supervisors’ needs, it is clear that supervisors are as diverse in their approaches and needs as the students they supervise. As a community they need stewarding (Wenger et al., 2009), and careful selection of tools and approaches is required to ensure that their experiences are authentic, easily accessible and useful. At present the institutional virtual learning environment is the focus for the University of Aberdeen community of educational researchers. Whilst the provision of this online community space has advantages (for example in terms of privacy and support availability), it also presents challenges for supervisors, both technologically and in terms of favouring engagement with the closed university community rather than a wider learning community. Further work is needed to explore alternative technological models for support, for example with open access tools or social networking, that offer authentic support for practices that students will take with them as they continue to practice enquiry in their professional contexts.