Simon Clarke, Shetland College, University of the Highlands and Islands

Videoconferencing (VC) has now been used to support students at centres remote from their tutors for the better part of two decades. A flurry of studies were published in the late 1990s and early 2000s, setting out the problems and opportunities of the medium and looking at success and satisfaction rates compared to conventional teaching (Pitcher, Davidson, & Goldfinch Napier, 2000; Knipe & Lee, 2002; Badenhorst & Axmann, 2002). However, even more recent analysis has almost invariably been based on pilot studies and conducted on relatively small groups of students (c.f. Gillies [2008], which looked at data from just 15 students on one course and Hoyt, Howell, Lindeman and Smith [2013], which looked at two modules enrolling just thirteen students each). The University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) is Europe’s largest educational user of VC and has been routinely teaching using VC since 2000 (Clarke, 2010, p. 6). In the later part of semester two of the 2013/14 academic year, students on UHI programmes with a significant VC element were invited to take part in an online survey using multiple choice / multiple answers and continuous text responses (see Appendix 1). One-hundred and ninety students drawn from thirty-one programmes responded, providing an authentic student voice on what it is like to take VC led modules within UHI. By looking at associations between students’ responses to different questions, it also provides a basis for reasoned analysis of why some approaches have led to a better student experience than others. Three broad findings will be detailed in this paper. Firstly, that VC teaching can be routinely used by remote students to access higher education comparable in quality to a face-to-face experience. Secondly, teaching decisions by individual staff and at institutional level have a substantial impact on student satisfaction. Finally, the study will demonstrate that significant differences exist in the perceived quality of the experience for different types of students (age, gender, level of study, circumstances of study), with important implications for how and when VC should be used to maximum advantage.

The central question of how students rated the overall experience of learning and teaching by VC was left to quite near the end of the survey so that respondents might first consider a whole raft of contributory factors. Students had a choice of five responses to the question “how do you rate your experience”. Just over 72% selected the top two classifications; “overwhelmingly positive” and “generally good occasionally falling short of its potential”. Almost half the remainder, 13.16%, selected the middle classification “good in parts but frequently falling short of its full potential”. Only six students, 3.16%, responded that the VC learning experience was “wholly inadequate …”. While six out of 190 is six too many, this is a remarkably low figure, bearing comparison with more conventional modes of HE delivery. There is the potential for surveys using this sort of Likert scales to gain an inflationary ‘positive’ effect by listing the “strongly agree” or “overwhelmingly positive” response first (Nicholls, Orr, Okubo, & Loftus, 2006; Hartley & Betts, 2010). However there is no evidence in this case that students ticked the first box they came to. The propensity for students in a hurry to do this has been reduced by varying the style of questions and the nature of the responses throughout the survey.

Table 1 Rating the overall learning and teaching experience

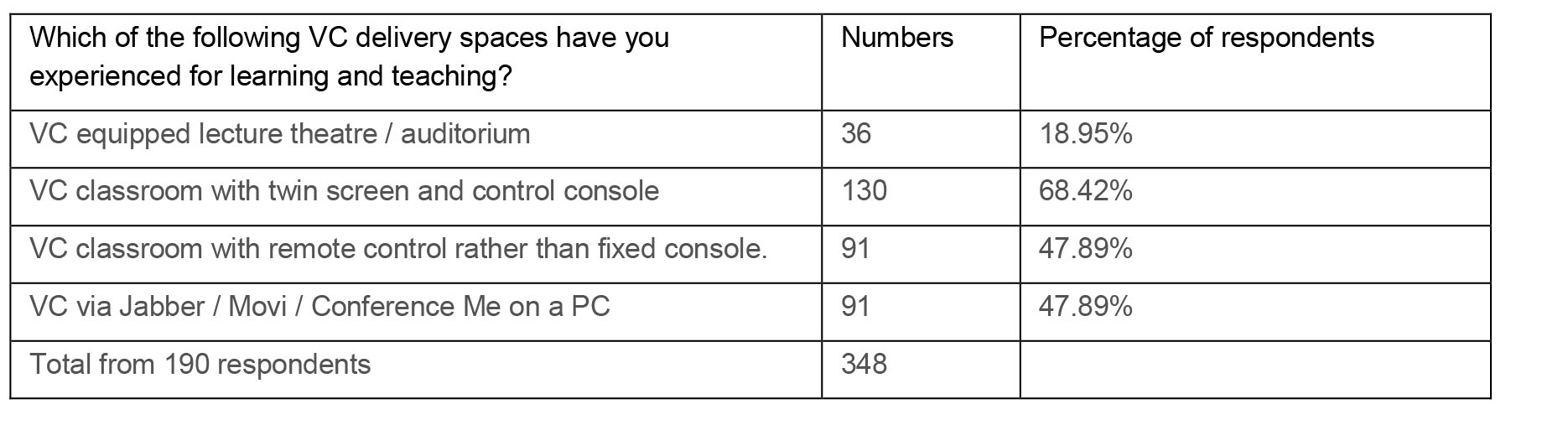

The learning environment is much more than just the physical classroom and the learning technology it contains – but this does form the crucial foundation to that environment, particularly for networked teaching (Zandervliet & Fraser, 2005). UHI uses a range of VC facilities, from large raked lecture theatres, down through various sizes of classrooms to units based in small offices.

VC auditoria capable of seating up to 100 students are available to students at quite a few sites; Inverness College, West Highland College (Lochaber), Moray College, SAMS and NAFC. However, for reasons which will become apparent, they are relatively little used and only a minority of students reported having used them (36 students, 18.95% of the sample). See Figure 1 for an example of this sort of VC space.

VC with twin screen with fixed console are quantitatively the most significant VC suits in UHI. There are about fifty of these units installed around the UHI partnership, and for most teaching purposes they are the VC space of choice so are in service a high proportion of the time and tend to be located in bigger classrooms intended for use by larger groups. Consequently, 130 students, or 68.42% of the sample, reported having used this type of space. See Figure 2 for an example of this sort of VC space.

VC with single monitor and remote control handset are more numerous, but are of a lower technical specification and tend to be in smaller classrooms so have consequently been used by a smaller, but still significant, proportion of students, 91 students or 47.89% of the respondents.

Personal Computer (PC) based VC rather than a dedicated VC suite is a relatively new phenomenon in UHI but has grown very rapidly – 91 students, 47.89% of the respondents, reported having used it to access teaching. UHI is currently exclusively using Cisco’s Jabber system (formerly called Movi), but until 2013 it also used Cisco’s (now defunct) Conference Me system. Relatively low specification PCs with a few peripherals and some downloaded software potentially allow access from a vastly expanded range of locations (UHI Learning and Information Services, n.d.). The system is being used from UHI campuses, non-UHI public places (such as libraries and community centres) and from private homes (see Figure 3).

Table 2 Experience of different types of VC suite

As the table below shows, the type of hardware and its accommodation appear to have a relatively weak influence on students’ perception of quality. (Note that students are commenting on all the types of space they have experience not just the type filtered for). As one student noted “when they are used properly, they work well”.

Table 3 Rating the student experience filtered by experience of different VC suites

Generally, students were very positive about the VC spaces they used, even those that didn’t like the study mode conceding that it was done as well as could be expected for the medium. However, VCs were not always configured appropriately as classrooms, and occasionally there was an issue with allocation of inappropriately sized rooms for the local class size. One student complained of a space suitable for one student being used by three and that there was “not enough desk space for taking notes”. Another issue was classes being too large to sit within the camera’s widest angle. At the other end of the spectrum, students reported that their VC space was ridiculously oversized, and in one case a lone individual had been assigned to an auditorium VC. This type of space was singled out for specific criticism frequently relative to the small numbers of students that have used it. These largest spaces were the least effective due to the inability of microphones to pick up comments from the students and the tendency of students to spread out to maximize the distance between themselves and their neighbour like passengers in a railway carriage! This was recognised as inhibiting student interaction even locally. Above all, the use of such a big space is very rarely justified by the size of the class attending. Ironically, these most expensive VC suites appear to be used as the VC space of last resort.

Over half of student returns included comments about the technical reliability of the live VC. Where detail was provided, the most common complaint was getting connected to the VC session, with audio or image quality coming a close second. Bandwidth for off campus, and even smaller learning centres, is one significant factor beyond UHI’s control, but quite a few of these ‘technical problems’ are quite likely to be ‘pilot error’ of some sort – administrative errors, incorrect equipment set up or use etc. – rather than hardware failures. One student suggested that some sort of “confusion does occur in about 1 in 10 VCs”. Probably the most important lesson to draw from this is that an additional layer of complexity brings the likelihood of at least occasional, and potentially quite debilitating, technical and administrative failure, requiring development of a ‘Plan B’.

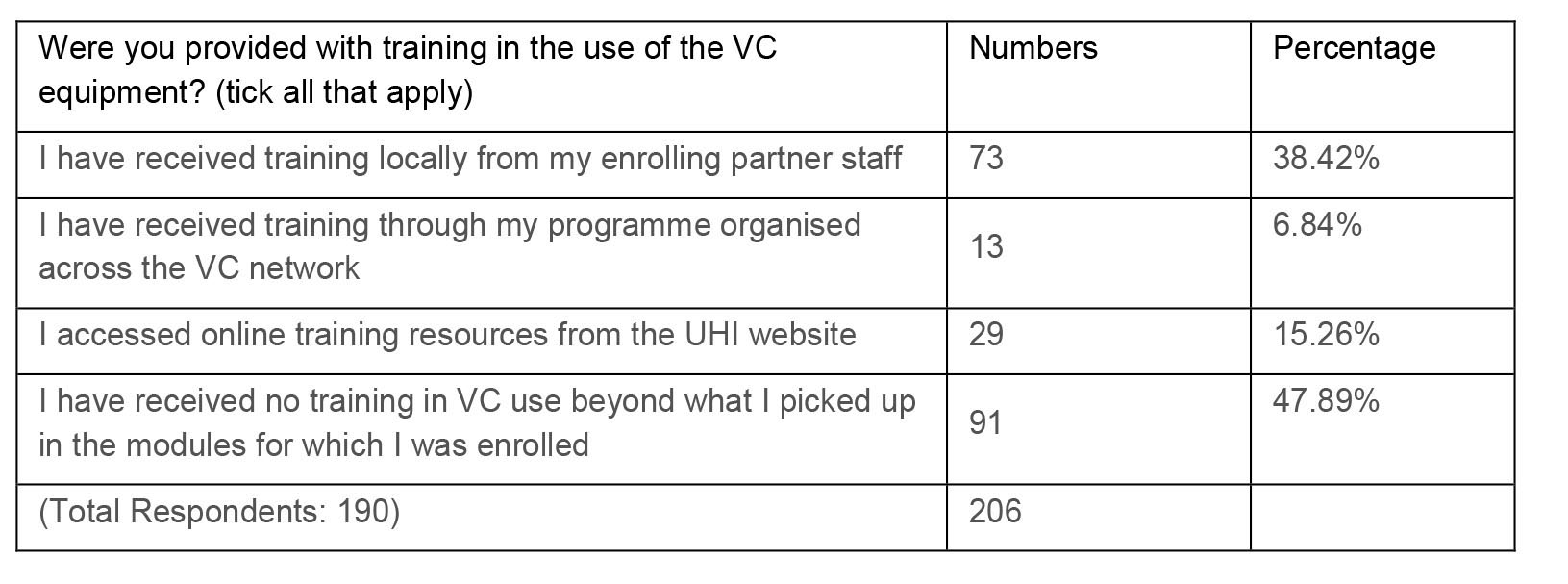

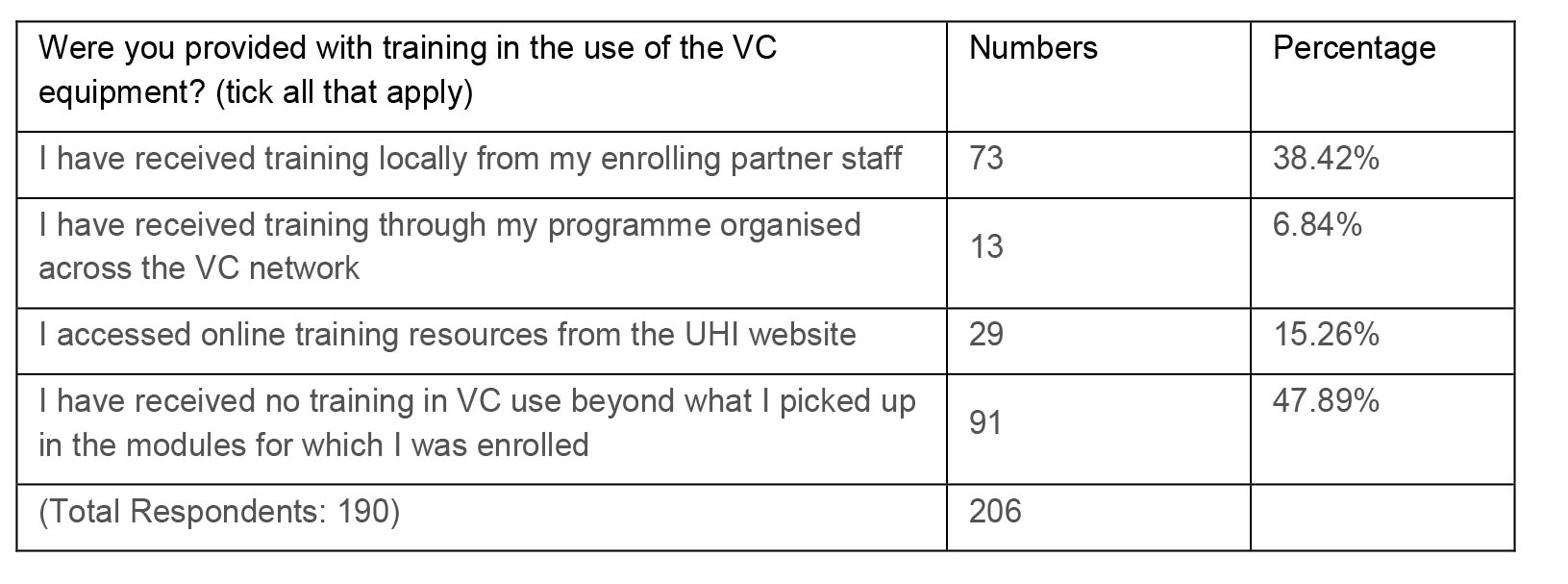

Any programme of learning and teaching through the medium of VC might reasonably be expected to include training in the use of the technology itself. In UHI, this is available through a number of different routes. Most programmes provide students with an induction, and in many cases this included an introduction to the VC technology they would be using. This might be through local staff at the enrolling centre or through a VC-supported introductory session. Some programmes also scheduled study skills sessions later in the academic year, including introductions to VC technology and VC etiquette. UHI also has online materials in PDF and video clip formats outlining specific aspects of the technology, such as use of the VC console and how to access VC recordings (UHI LIS, n.d., UHI Learning and Teaching, 2012). However, one of the findings of this survey has been that student uptake of these opportunities has been very variable, almost half accessing no training.

Table 4 Uptake of VC training

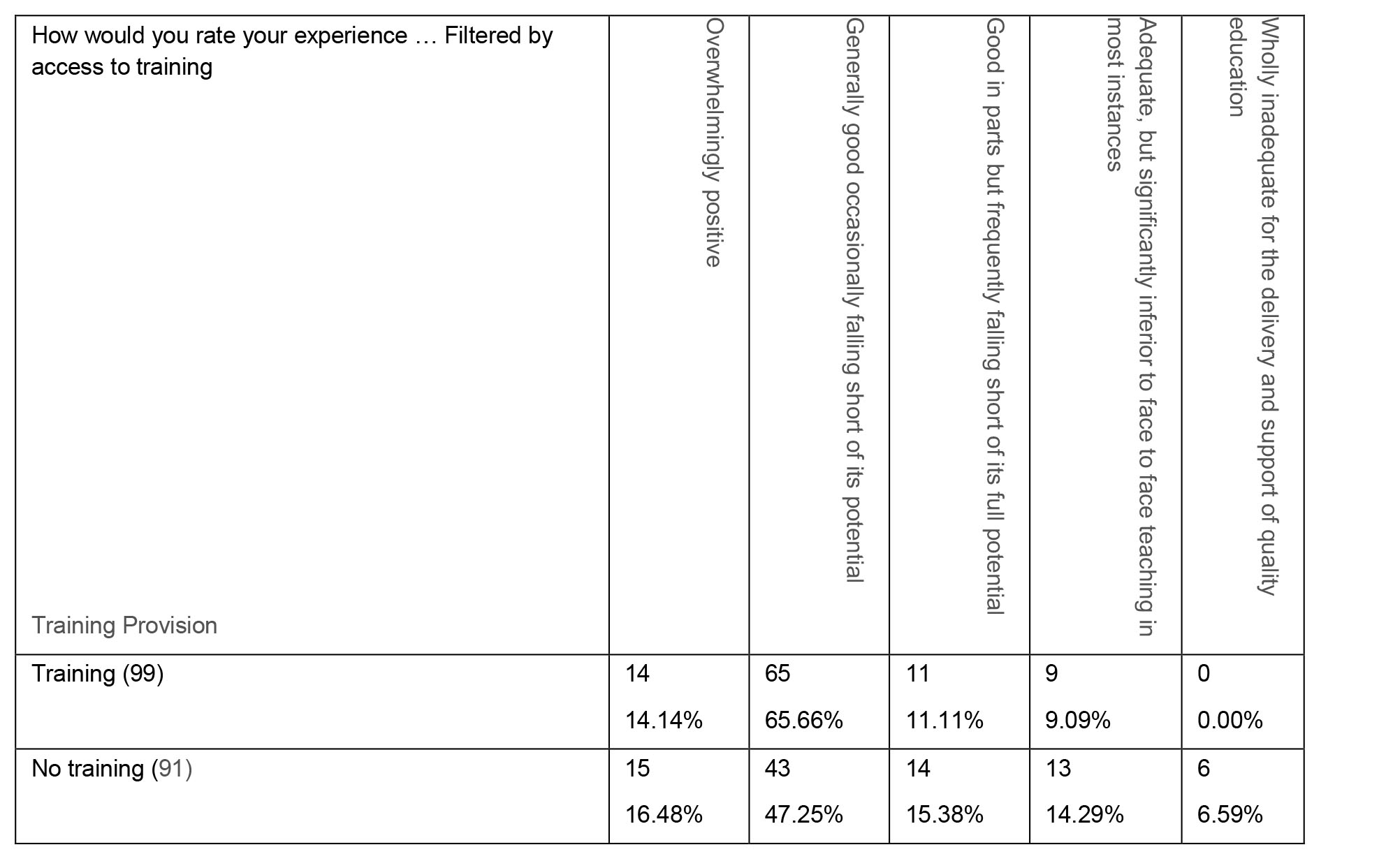

Where training was accessed, only a couple stated that training was “not very effective”, “sink or swim”. The vast majority that expressed a view thought that it was “good enough”, “adequate”, “sufficient” or “satisfactory”, or at the more effusive end of the spectrum, that it was “well done”, “very effective” and “straight to the point”. One explanation for uptake is that the “system is self-explanatory”, and it was “fairly easy to pick up on my own”. However, while students might not have felt the need to access training, there was quite a strong correlation between uptake and their overall satisfaction with the VC experience. No one that had accessed training thought that VC was “wholly inadequate”, and they were also about 15% more likely to place the experience in the top two satisfaction categories (see below).

Table 5 Rating of the VC experience filtered by whether training had been received

Although the majority of UHI’s VC equipment come from a single supplier (Cisco/Tandberg) and are described by students as “quite intuitive as a system”, the diversity of units has resulted in a lack of consistency in the controls between different models. As a result, one student reported “nobody is confident” on the equipment. ‘Nobody’ is clearly an overstatement, but the lack of standardisation is generating anxiety amongst students (and staff) and places additional demands on training which are not always met.

While technical failure is significant, at least as many students identified the key issue as “mainly how it is approached by the lecturer rather than the technology”, “some tutors seem more at home teaching on the VC than others” and “the success or otherwise very much depends on the skills of the lecturer in grasping the possibilities and using it fully”. Good teaching in general and “tutors who really understand the medium” were named as key factors in VC sessions success in twenty responses. Conversely, staff lack of proficiency was identified as a problem in eleven responses. A significant number of students commented on difficulty with or lack of interaction in their VC classes. Three specified discussion being dominated by just a few students, another three on lecturers exclusively focused on their own location to the exclusion of the remote sites. A further thirty commented on difficulty of interaction in VC sessions more generally. “Some lecturers just talk for the whole hour without asking for any student input, it's quite hard to concentrate on a computer screen for that length of time”. Suggesting future improvements, five students stressed the importance of addressing remote students as well as those in the same location as the tutor. A further fifteen urged that classes should be more interactive generally.

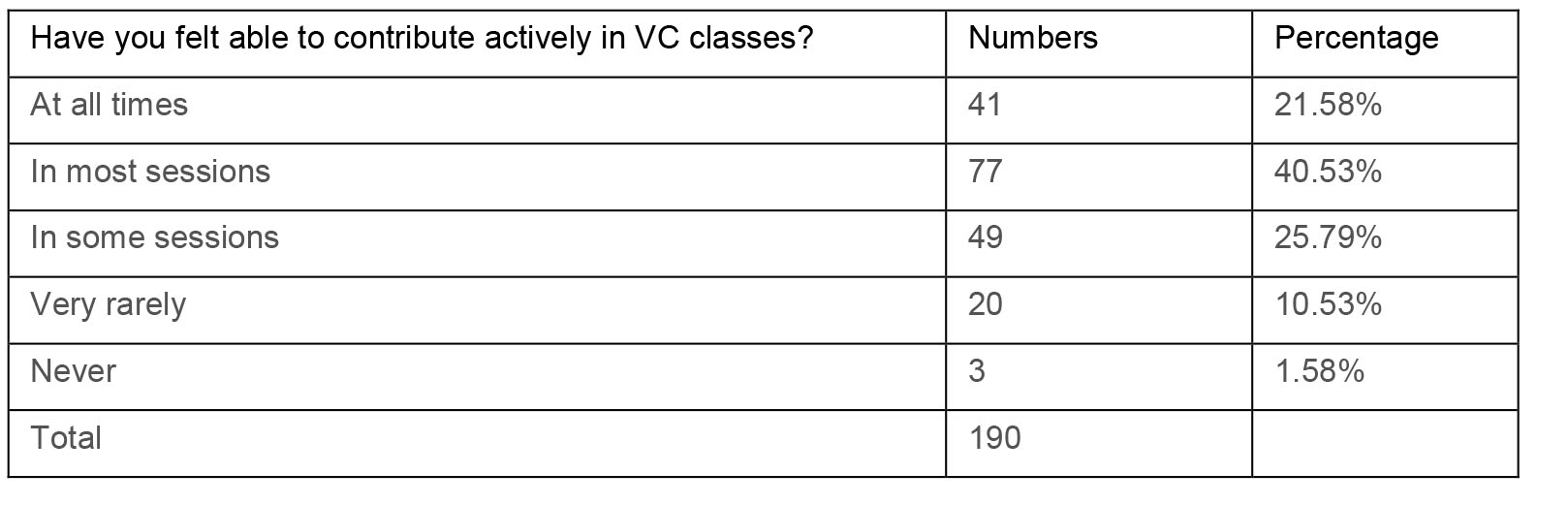

Students’ behaviour in the VC environment is also highly significant and tutors and local support have an important role in shaping it. The tendency of some students, particularly those new to the medium, to approach VC classes with a passive television viewing mindset needs to be challenged (Calodine, 2008, 242–243). One student noted that “students feel very intimidated and hold back quite a lot, where normally they would take part”. Tutors are therefore urged to help “make people feel comfortable about getting their point across”, “build in Q&A time to the lesson structure”, even to “expect students to take turns in leading the discussions”. Three students complained about discussion being hijacked by individuals or small groups, and a further three of disruptive chat or behaviours while the local centre was on mute. While a clear majority of students, 62.11%, felt able to participate actively in the learning process in most of their VC lessons, given the importance of interaction UHI should aspire to a much higher number. Only 12.11% rarely or never felt able to contribute, but one in eight students that have responded to a survey remaining disengaged from their actual learning is a major failing.

Table 6 Student interaction in VC classes

Filtering overall satisfaction with the VC experience by students’ perceived ability to contribute revealed dramatic variability. Of those who always felt able to contribute, 41.46% reported the experience as “overwhelmingly positive”; none reported it “wholly inadequate”. Where students reported “never” being able to contribute, none gave the top satisfaction rating and one third gave the bottom one. The number of students in this category was tiny (just three), but the picture it paints is entirely consistent with the overall pattern, with each successively worse category of interaction and inclusion reporting cumulative falls in overall satisfaction.

Table 7 Rating of the VC experience filtered by whether students felt able to interact

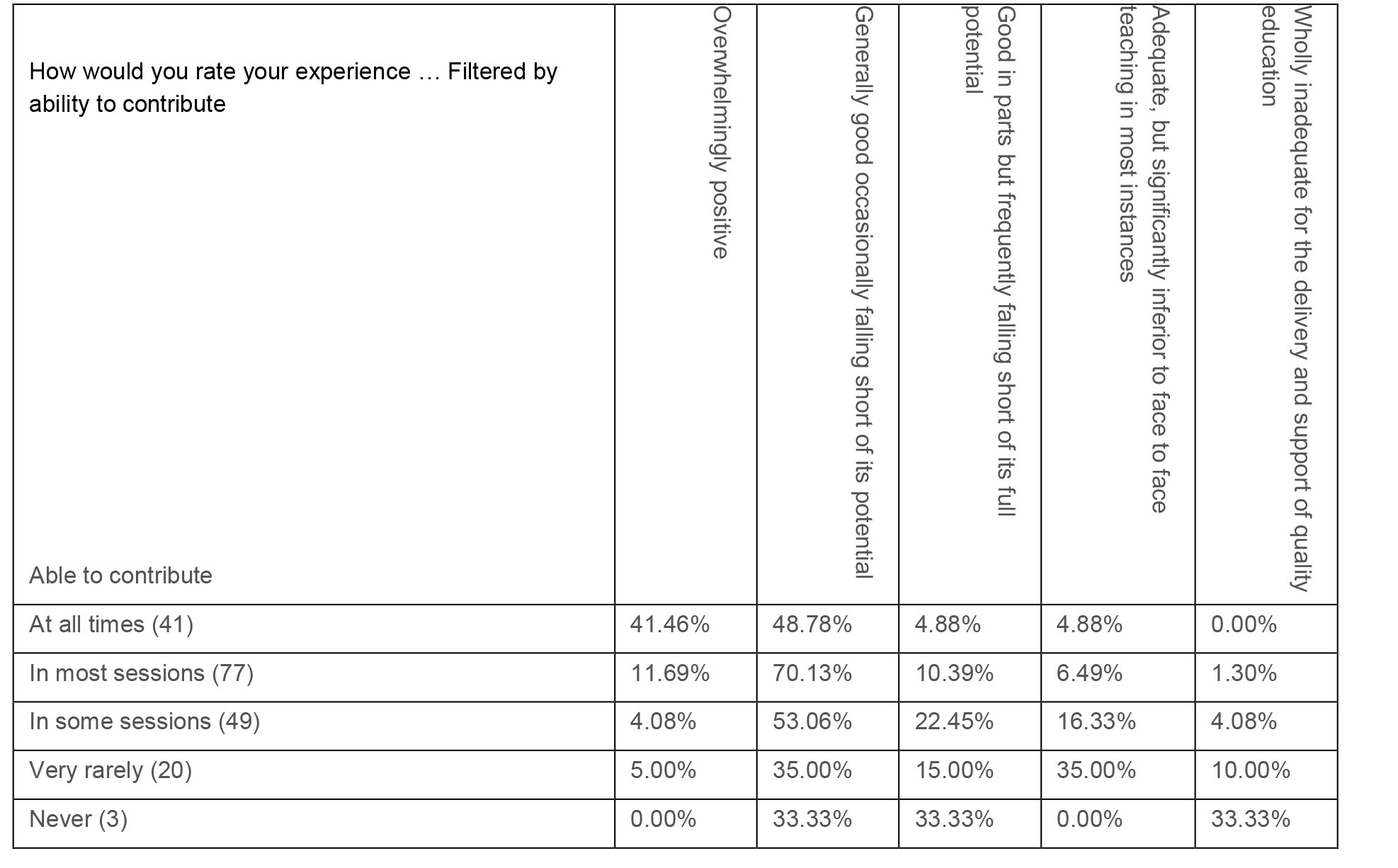

One potentially quite interesting aspect of the VC learning experience is that there is not a conventional front and back to the class. Both students and staff participate through essentially the same devices and therefore are on a near equal footing. While some staff will undoubtedly be uneasy at this social levelling, arguably it is entirely appropriate in an adult educational context. Students can, and do, make presentations and lead discussions over the VC. Just over 46% of students reported having used the VC in this way. However, VC satisfaction was only very slightly higher amongst students that had used the VC to make a presentation themselves, relative to those that had not. It needs to be remembered that long presentations by students are no more likely to be engaging for the rest of the class than those by the tutor.

Table 8 Rating of the VC experience filtered by whether students have made a presentation

Typically a UHI 20-credit module (notionally 200 hours of learning) will be supported by just two hours per week of VC teaching for twelve weeks of the semester (the last weeks being reserved for final examination). Clearly, therefore, VC is, or should be, only one part of the learning and teaching package. No specific questions were asked about use of VLE in support of VC teaching in this survey, but elsewhere the author has argued that no VC led module should be attempted without such a resource (Clarke, 2009). One reason is that any technologically dependent mode of delivery needs to have a Plan B to fall back on in the event of a failure (Winslow, Wiggins, & Carpio, 1998, p. 130). The other is that, as has been shown above, a key feature for success in VC teaching is interaction. Although the term “flipping the classroom” was coined for the conventional face-to-face environment (Sams & Bergmann, 2013), delivering the content element of teaching elsewhere is a highly effective tactic for VC. It is therefore highly significant that ten students reported that notes and other online materials were sometimes inadequate or posted very late. One student commented “staff seemed not to understand how to use the Blackboard system (and email), and all use it differently – no consistency … the forums are used poorly by [module] leaders”. Two other students complained of poor communication by email, while three commented that it was difficult to get access to, or get to know, the tutors based at remote sites; for example, “it's hard to get to know your lecturer well enough to ask them for a reference”.

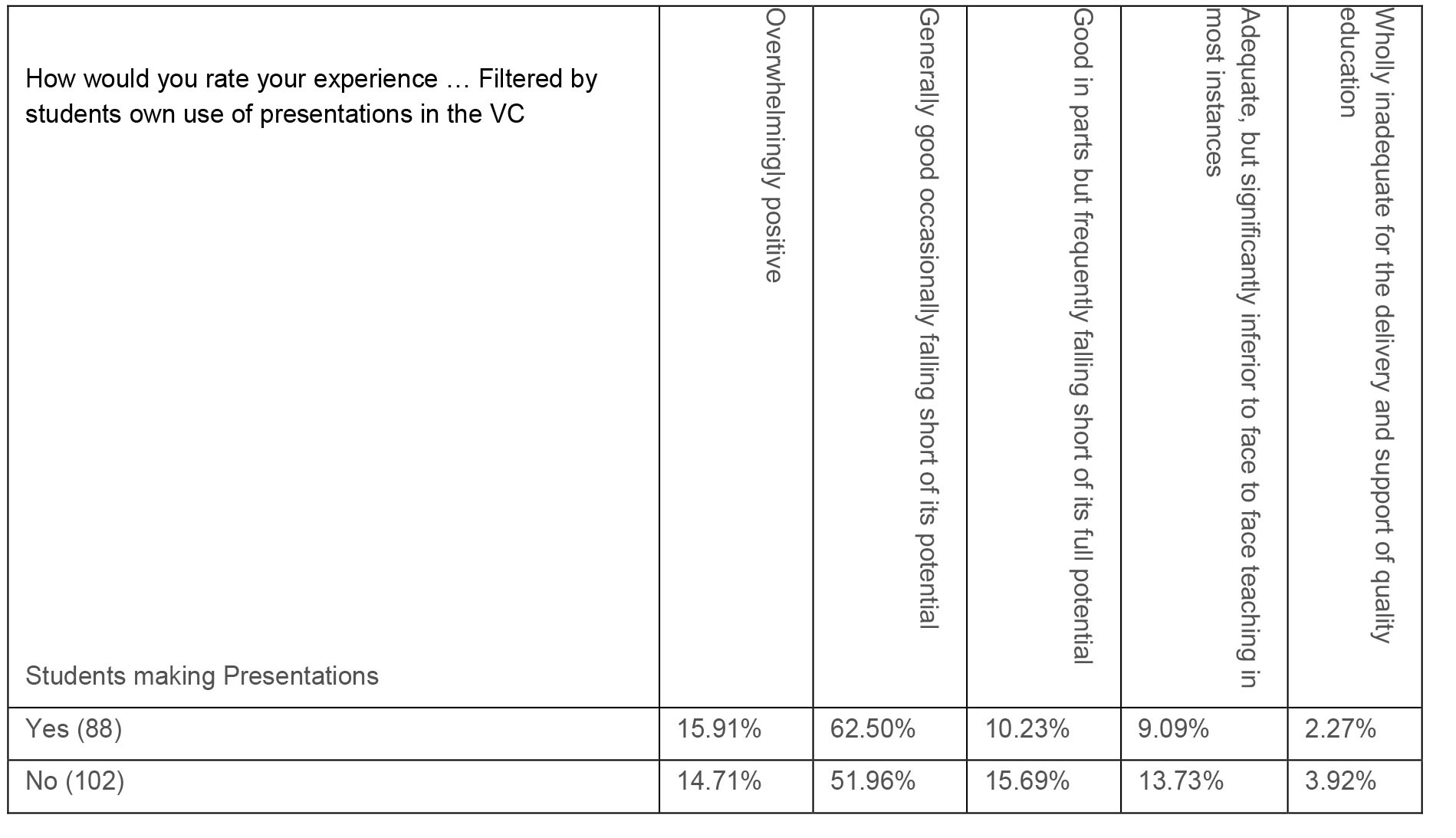

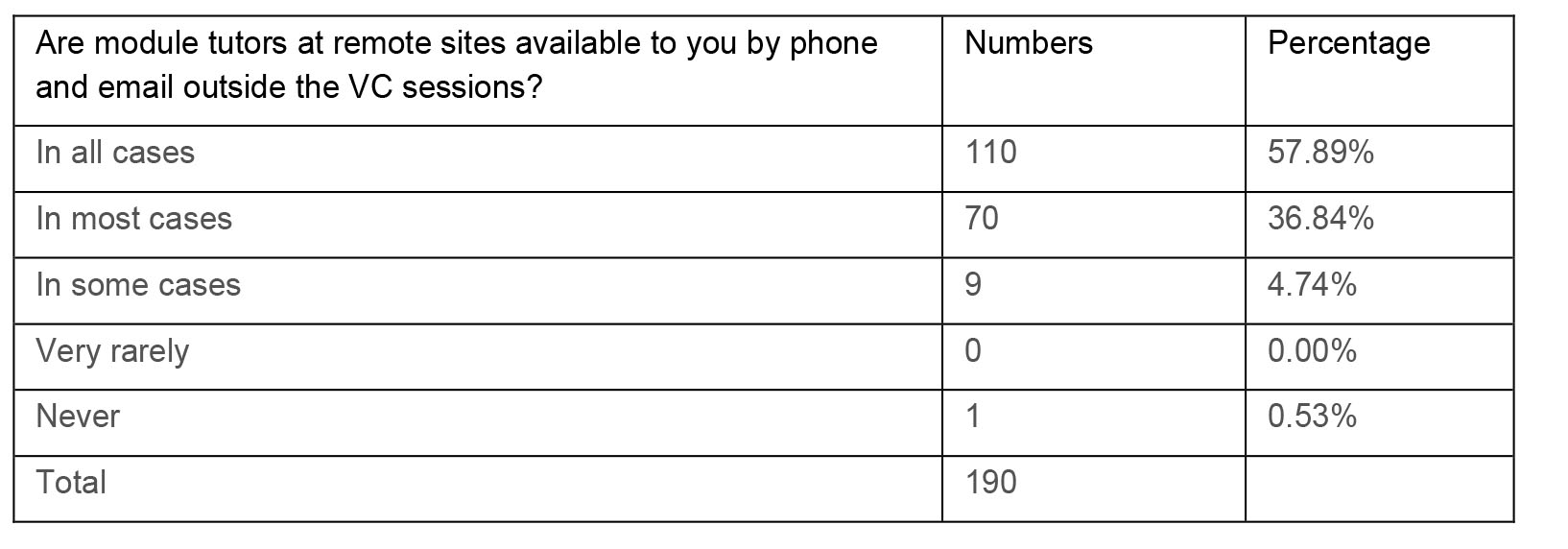

Table 9 Students’ perception of access to VC tutors

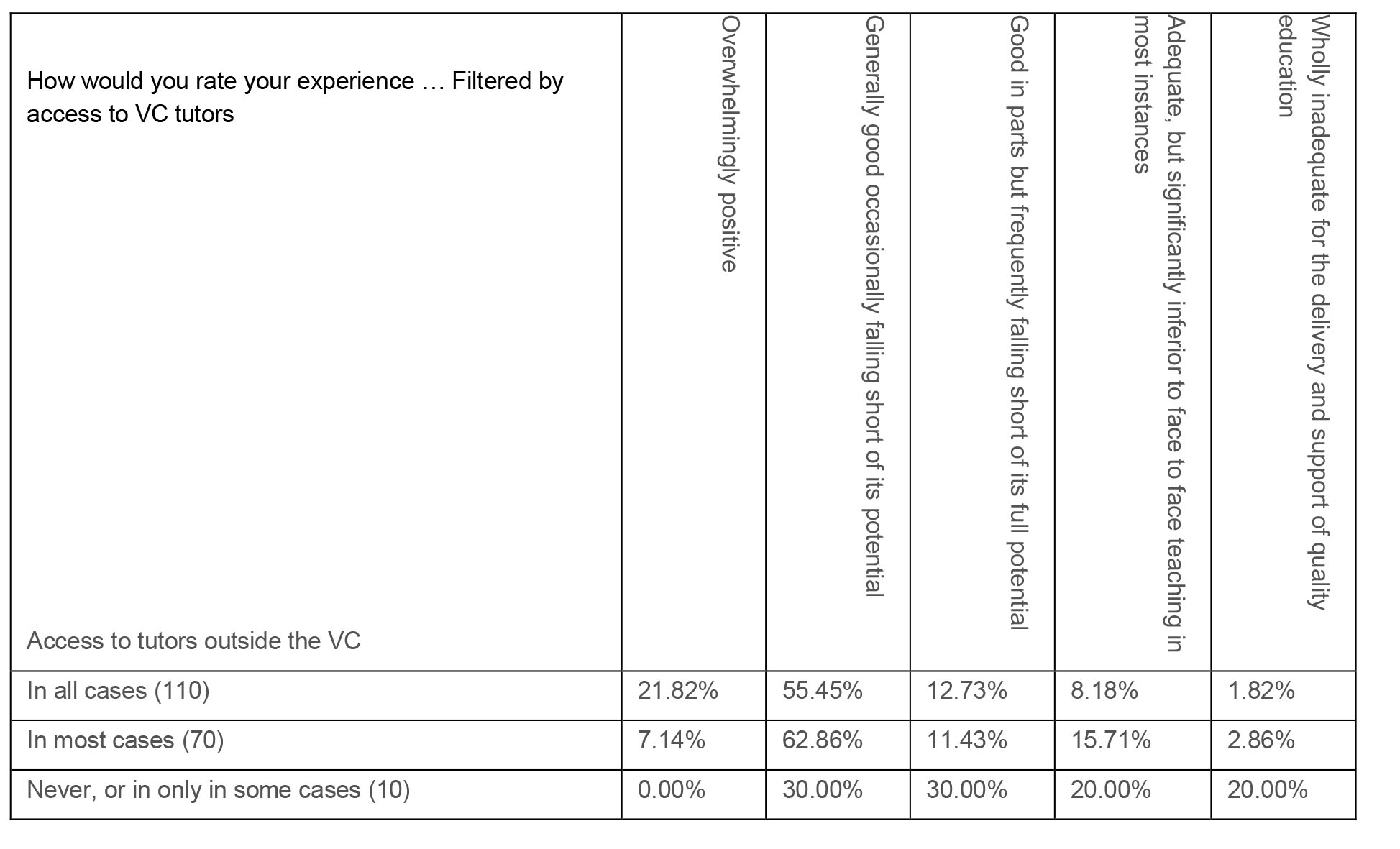

On the face of it, the availability of VC tutors by email and over the telephone appears very positive. Over half (57.89%) reported them accessible “in all cases”. Most of the rest (36.84%) reported their tutors available in most cases. Less than five percent (ten students) reported staff only available “in some cases” or “never”. It would be dangerous to assume there is a causal link, but there is a clear statistical association between better perceived access to the tutor and better student satisfaction ratings (see Table 10). Of students reporting access to their tutors “in all cases”, 21.82% rated the VC experience “overwhelmingly positive” and just 1.82% rated it “wholly inadequate”. Of students reporting access to their tutors “in most cases”, 7.14% rated the VC experience “overwhelmingly positive” and just 2.86% rated it “wholly inadequate”. Amongst the ten students claiming that they had “never” or in only “in some cases” had access to tutors, the pattern was even more extreme with none reporting the top satisfaction rating, and 20% of the sample rating it “wholly inadequate”.

Table 10 Rating of the VC experience filtered by students’ perception of access to VC tutors

Streamed recording of VC classes is another facility that has (like PC-based VC) been introduced relatively recently to UHI, replacing recordings on DVD or videotape and distributed by post. The VC service at UHI has the capacity to record up to fifteen high-definition VC sessions simultaneously, and has the storage capacity for recorded lessons to remain available online for the whole semester. These can be made available to students via a hypertext link distributed either by email or from within a module VLE space (UHI Learning and Information Services, 2012). Many students commented on the usefulness of these recordings, twenty-seven mentioning mitigation in the case of missed classes, one specifically a case of technical failure. Three students also mentioned the reassurance it gave them, even when it was not needed. The resource was also reportedly used for purposes of review and revision by 22 students. One student reported that it helped them manage their dyslexia, as accurate note taking was difficult for them with the live sessions alone.

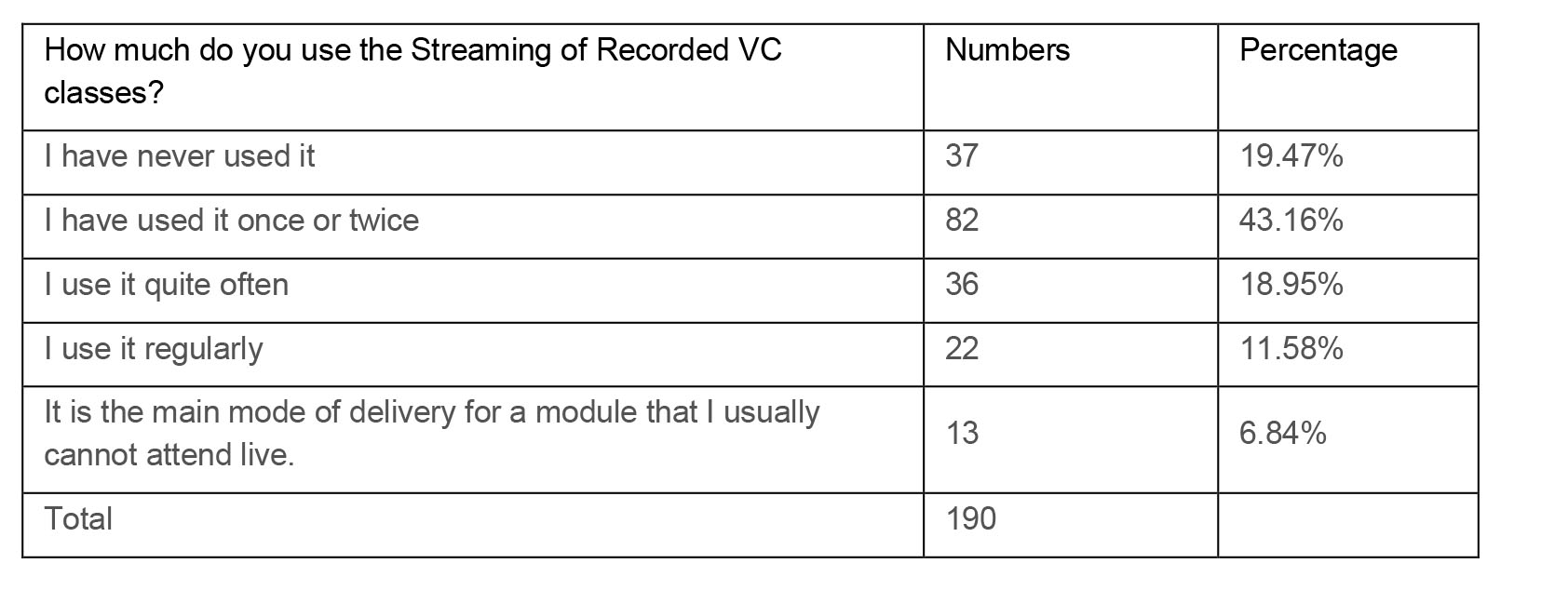

Although generally refuted in the wider literature, persistent fears remain amongst staff that recordings undermine student attendance (The Learning Institute, 2012). Similar fears, also dismissed, exist in relation to making notes and slides available ahead of lectures (Babb & Ross, 2009). In spite of the ease of use, over 62% of students have never or only very occasionally used this service. In most cases, this is despite the fact they have taken multiple VC modules. Engstrand & Hall (2011), looking at use of the facility in UHI in 2010/11, found that 39% of recordings were never accessed at all. A very high proportion of Higher Education VC lessons are now recorded, so both statistics rather beg the question whether this is appropriate use of resources.

Table 11 Students’ use of streamed recordings

Alarming for different reasons is that thirteen students (6.84% of respondents) use the streamed recording as their main mode of delivery. Students themselves noted the recording is not as useful as being present at the live lecture, because there is not the opportunity to interact. If interactivity is important to the educational success of the VC sessions, then a diet of one-way broadcasts cannot be a heathy option. Is VC recording at UHI facilitating a dangerously passive student experience?

Table 12 Rating of the VC experience filtered by students’ use of streamed recordings

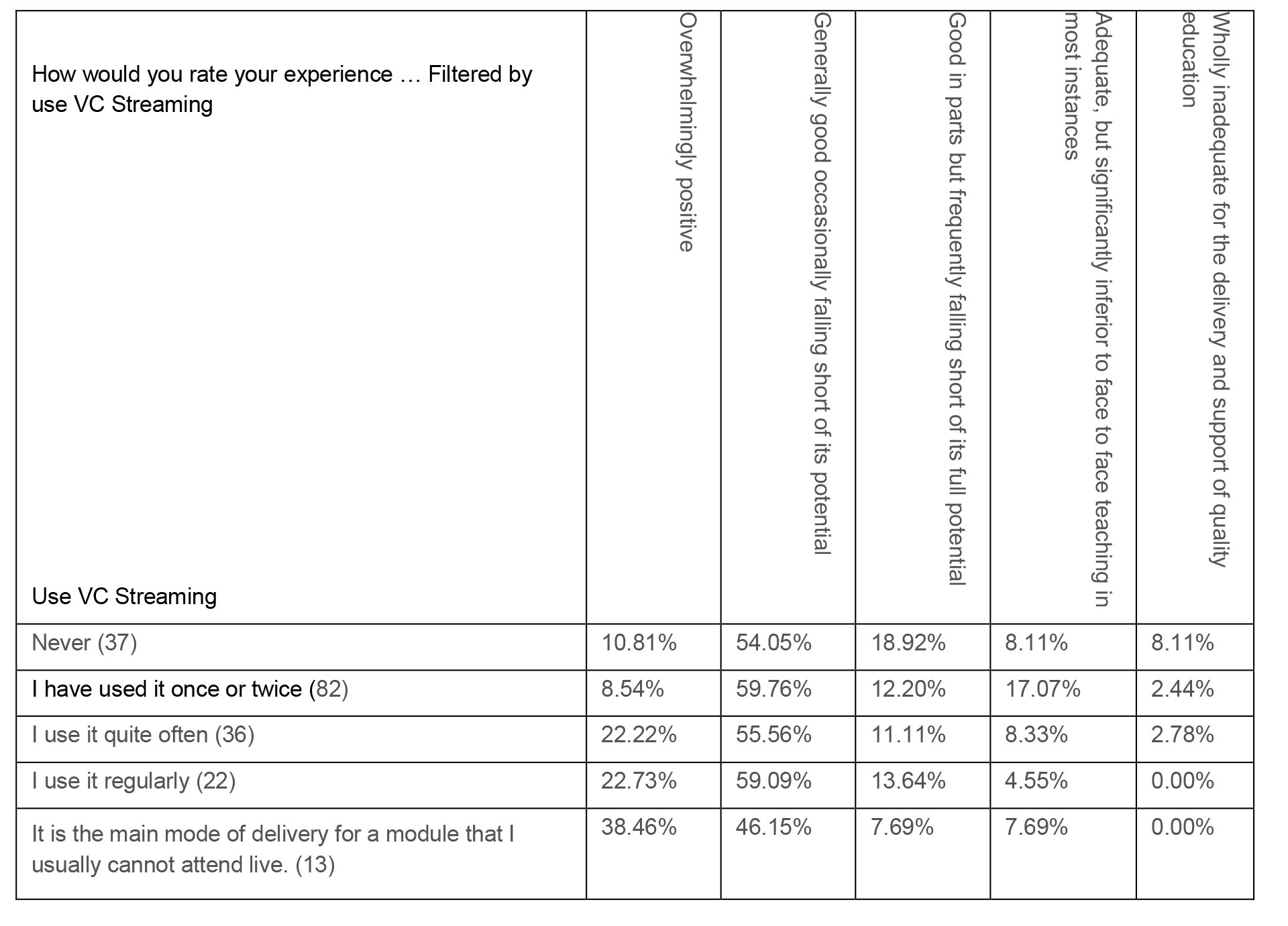

While learner-centred teaching should not be simply catering to students’ desires (Anderson 2008, p. 47), an emphatic answer to the issue of resource allocation appears to be provided by the satisfaction rates of students when filtered by their use of the streamed recordings. Looking at overall satisfaction filtered by the use of streamed recordings, there is a very strong association between use of the recordings and the most positive responses. Amongst those that had never used the service (thirty-seven students in total), 10.81% reported the VC experience “overwhelmingly positive” and 8.11% “wholly inadequate”. Amongst the twenty-two students using it “regularly”, 22.73% reported the highest and none the lowest satisfaction rating. Amongst the thirteen students using recordings as a substitute for attending live sessions, the satisfaction rate was even higher, 38.46% reporting the experience as “overwhelmingly positive”, with a further 46.15% reporting that it was “mainly good”, the second highest rating. Satisfaction rates’ relationship to use of recordings is also somewhat counter-intuitive if active learning is the key to successful pedagogy. One possibility is that uptake of streamed recording is incidental to the real factors for success. Students can only access recordings if they have been made available by tutors, for example by placing them on a well-signposted area within the module VLE. Is it actually good management of the VLE more generally that is crucial? Alternatively, it may be the character of the students that is the key factor for a happy outcome; showing initiative and using every opportunity available to them.

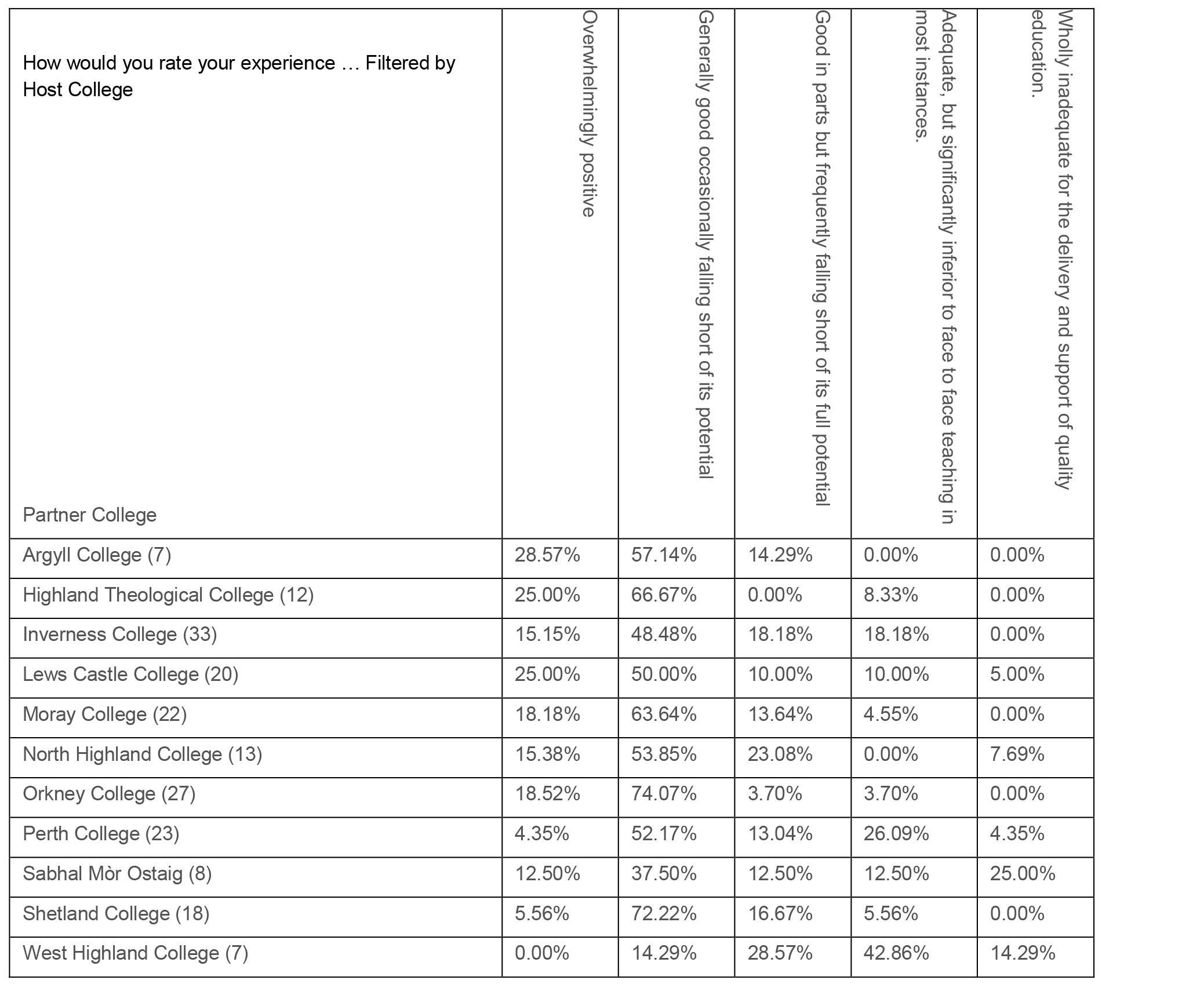

The majority of programmes accessible to students through the medium of VC are available throughout the UHI partnership. However, the importance of VC delivery to the different partners varies considerably. Inverness College, the largest partner, predictably had the largest number of respondents (33 students), but Orkney College came second (27 students), knocking the much larger Perth (23 students) and Moray (22 students) colleges into third and fourth places respectively. Two other island colleges, Lews Castle (20 students) and Shetland (18 students), were not far behind in terms of students responding. It is evident that some of the smaller colleges have made much greater use of this technology than their larger partners, which generally have a wider range of conventional face-to-face programmes available.

Table 13 Rating of the VC experience filtered by enrolling college

When the survey was filtered by UHI partner a startling disparity in satisfaction rates emerged. Some colleges (cf. Argyll College, Highland Theological College and Orkney College) have high proportions of students selecting “overwhelmingly positive” or “generally good”, with few or none responding with only “adequate” or “wholly inadequate”. In contrast, other partners (c.f. Perth, SMO and WHC) have small proportions of students selecting the most positive responses, a much higher rate of dissatisfaction. The significance of the results should not be overstated given that the sample sizes at individual colleges are in some cases small. For example, the 25% reporting the VC experience as “inadequate” at the Gaelic language College SMO is actually only two students. However, in the larger groups such as Perth and Orkney Colleges, it is difficult to believe that there is not some profound root cause for the difference. Given that students throughout UHI are using networked modules, by and large universal to the partnership, it is likely that these differences reflect either the suitability of recruits selected for enrolment or the quality of support provided for them locally.

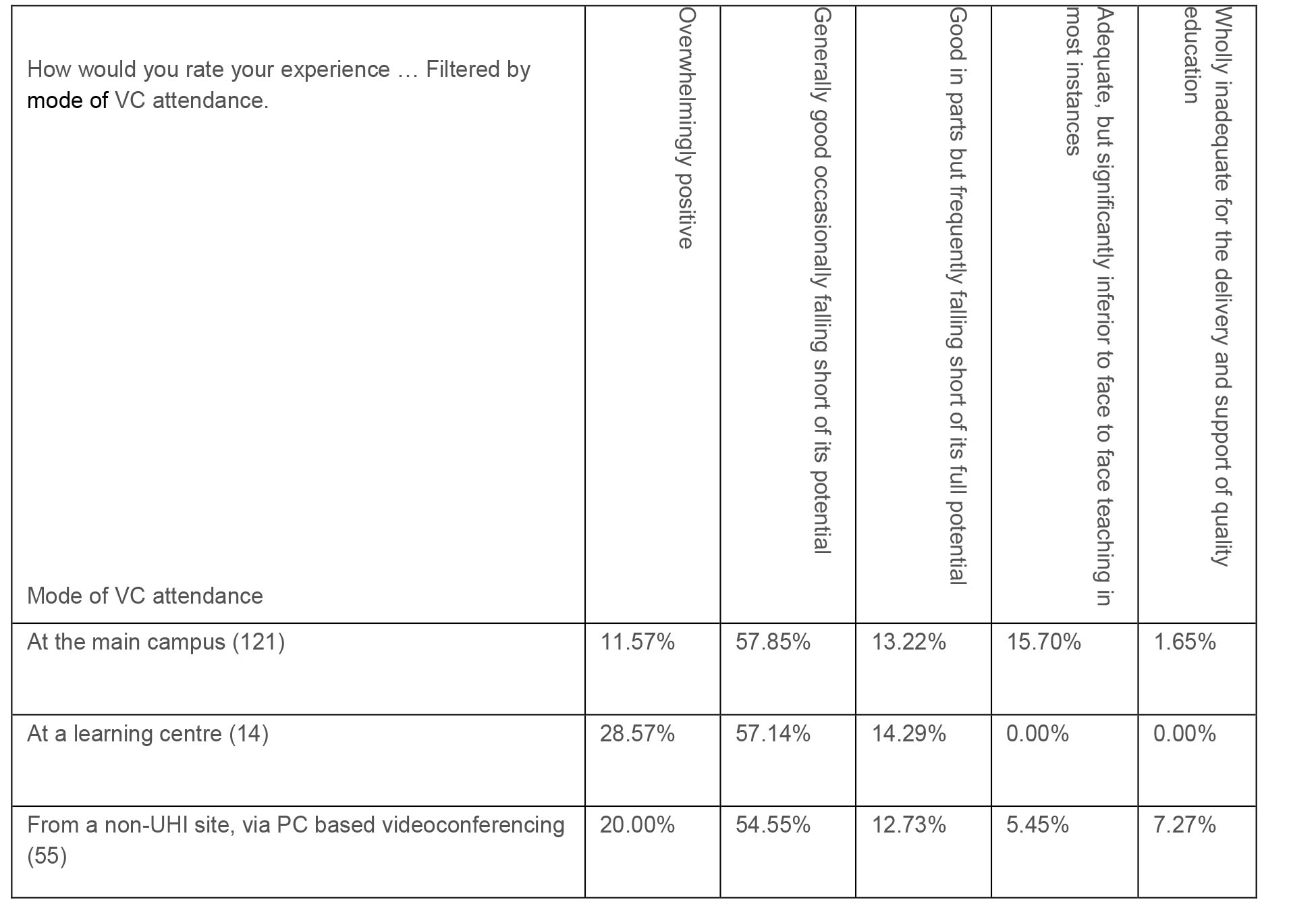

Students were also asked to specify their main mode of attendance. Did they attend VCs in their college’s main campus (63.68%), from a minor learning centre (7.37%), or from outside the UHI network through PC-based videoconferencing (28.95%)? The later might include access from non-UHI affiliated community centres, but in most cases meant through home broadband. The difference between the perceived quality of experience in this instance is somewhat counter-intuitive. Although the sample is small, learning centre students rate their experience as far superior to that of their peers at the main campuses. The much larger group taking VCs from outside the UHI network using PC-based VC was somewhat polarised in its opinion. PC-based VC from outside UHI had a small but significant minority with a dreadful experience, reporting “wholly inadequate” in a higher proportion of responses than the other categories of user. For the majority, however, the experience was better than average. PC-based VC users were less satisfied than learning centre students but in most cases reported a better experience than that in the technically far superior VC suites at the main centres. One factor is probably that the most remote students are more forgiving of technical and pedagogical shortcomings than those with access to a wider range of educational alternatives. Another possibility is that the convenience of study from home and the autonomy of controlling personal VC facilities (in particular the microphone mute) outweigh the disadvantages of simpler equipment and restricted bandwidth.

Table 14 Rating of the VC experience filtered by mode of VC attendance

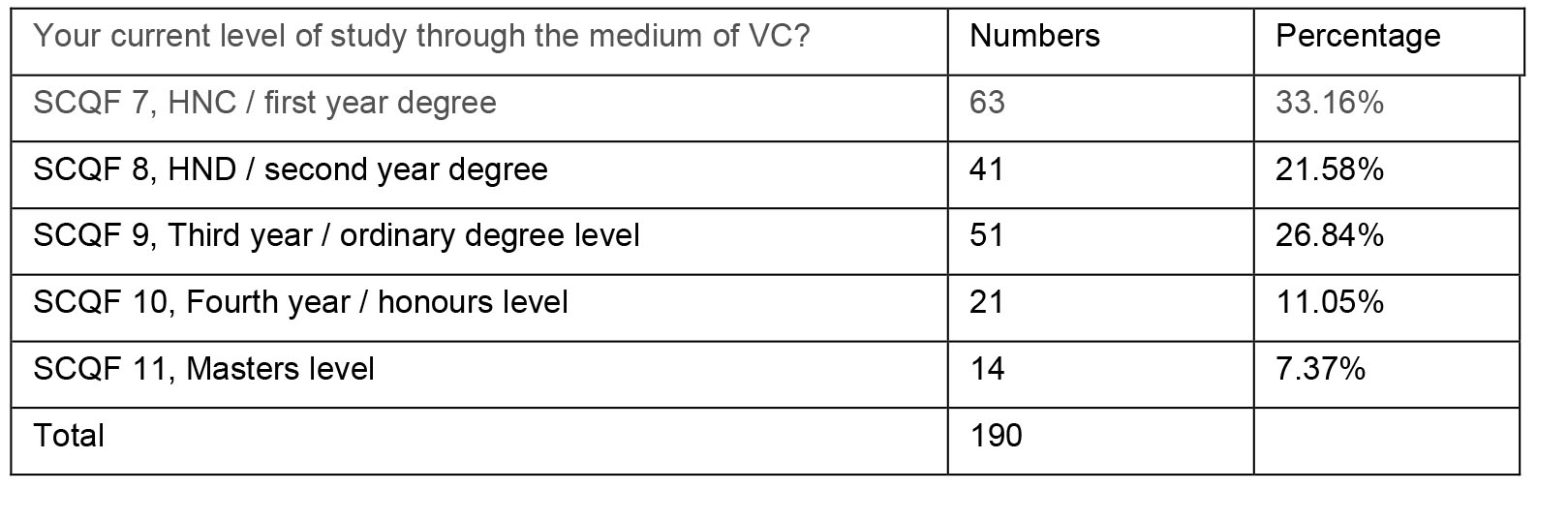

The survey was directed exclusively towards HE students on taught programmes and achieved good coverage at all five levels, from first year undergraduate to taught post-graduate. In contrast to many established universities, UHI has a highly flexible approach to certification. Most undergraduate programmes have interim certificated exit points prior to achievement of full honours degree, and students avail themselves of this facility fairly frequently. While some students do re-join programmes having taken a break from education, and advanced entry from outside UHI is also possible, this has inevitably resulted in a wedge-shaped level profile with smaller numbers in each successive cohort. That this is reflected in the respondents to the survey is entirely in line with expectations.

Table 15 Level of study

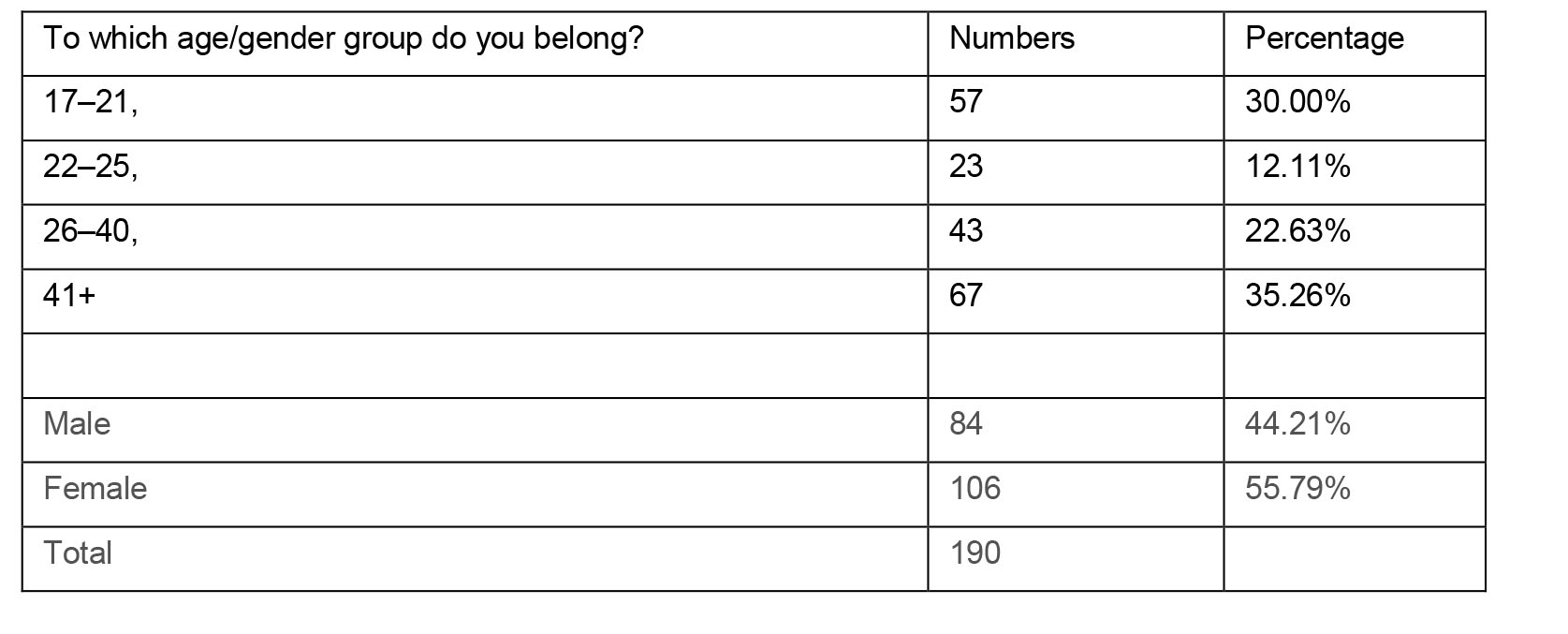

Satisfaction varied considerably between the different levels of study. The percentage reporting an “overwhelmingly positive” experience varied between 26.83% for second year undergraduate and 0% for final honours year. The percentage reporting a “wholly inadequate” experience varied between 9.52% for final honours year and 0% for both second year undergraduate and taught post graduates. There is no simple, easily explained trend here. It might have been expected that the smaller groups and more experienced students of higher undergraduate levels would have resulted in more effective support for more confident learners. It would also be natural for students that had struggled or disliked the VC-led experience at lower levels to have dropped out disproportionately. However, neither of these expectations is borne out by the trend within the undergraduate students. It seems likely that something about the character of higher level undergraduate modules is not as appealing to students. Rather different expectations are placed on students in terms of self-direction, reflection and critical capability at the higher levels. It may be that students are uncomfortable with this and/or that tutors are less adept at facilitating it. A rather less palatable possibility is that lower student numbers at higher levels result in poorer levels of preparation and online support by UHI staff. However, if that were the case we might expect the worsening trend to extend into the masters level taught courses, which tend to have even smaller student cohorts. In fact, they have the best satisfaction rates of all, an astonishing 100% of students rating their experience in the top two categories. As with all statistics, we need to beware the assumption that association implies a causal link. It is worth noting that other factors may have affected this small postgraduate group. Most masters level respondents are enrolled with Orkney College (one of the happiest partners in terms of VC experience), they have a different age profile to other programmes (more mature students, who also tend to be more satisfied with the VC experience, see Table 16) and they have a high proportion of participants via Jabber from outside the UHI network.

Table 16 Rating of the VC experience filtered by level of study

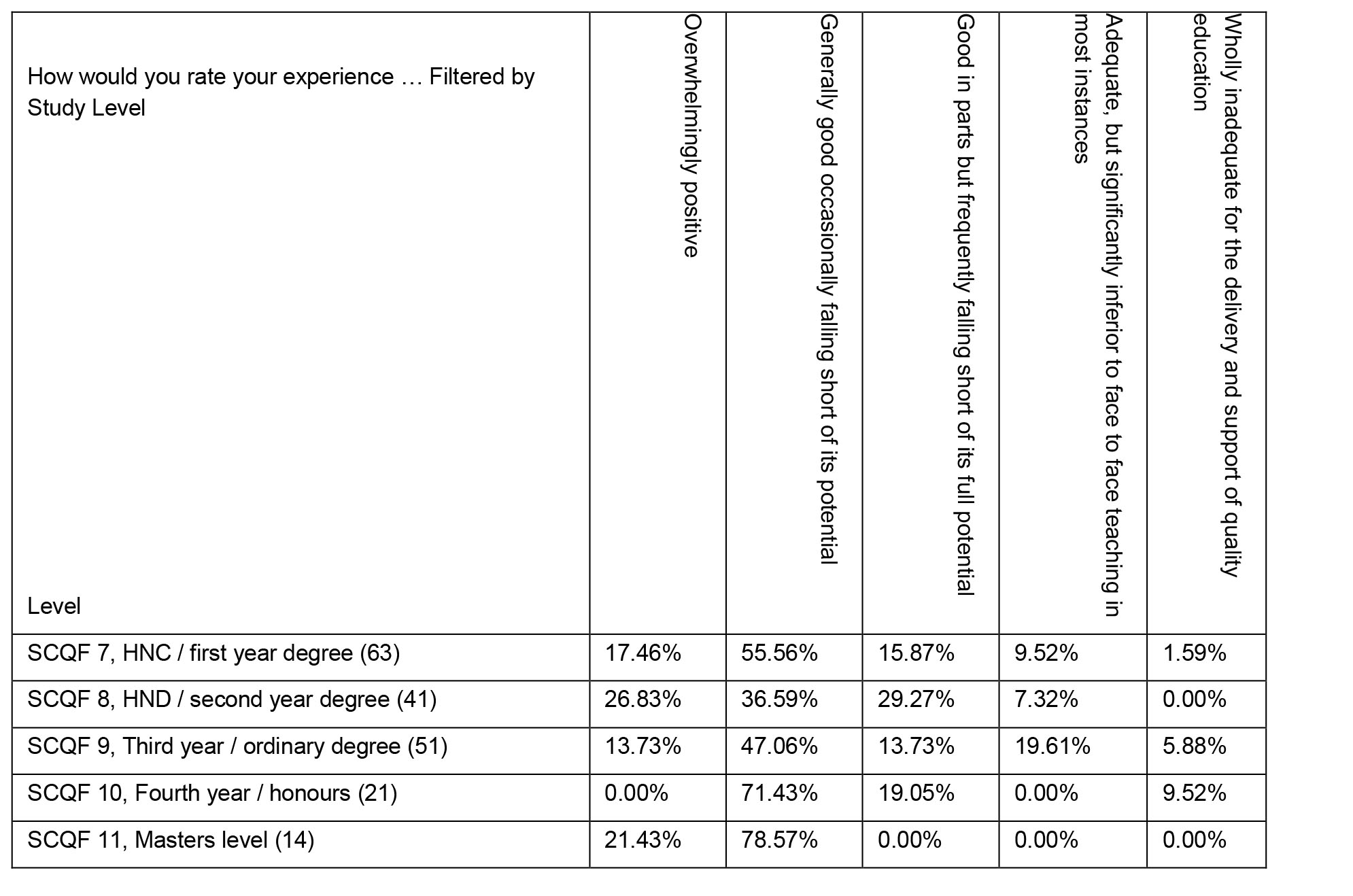

The age profile of students taking modules through the VC medium is also notably atypical of HE students in the UK generally. Only 30% of the respondents come from the traditional mainstay, the 17- to 21-year-olds straight from secondary school. The largest group are the over forties. This group made up only 2.1% of the UK’s undergraduate entrants in 1997 (Thomas 2001, p. 59). The gender profile is less extraordinary; women now outnumber men in many institutions and in UK HE generally by about 1.2 to 1 (Reay, David, & Ball, 2005). The disparity at UHI of 55.79% female to 44.21% male to is therefore unexceptional.

Table 17 Age and gender group

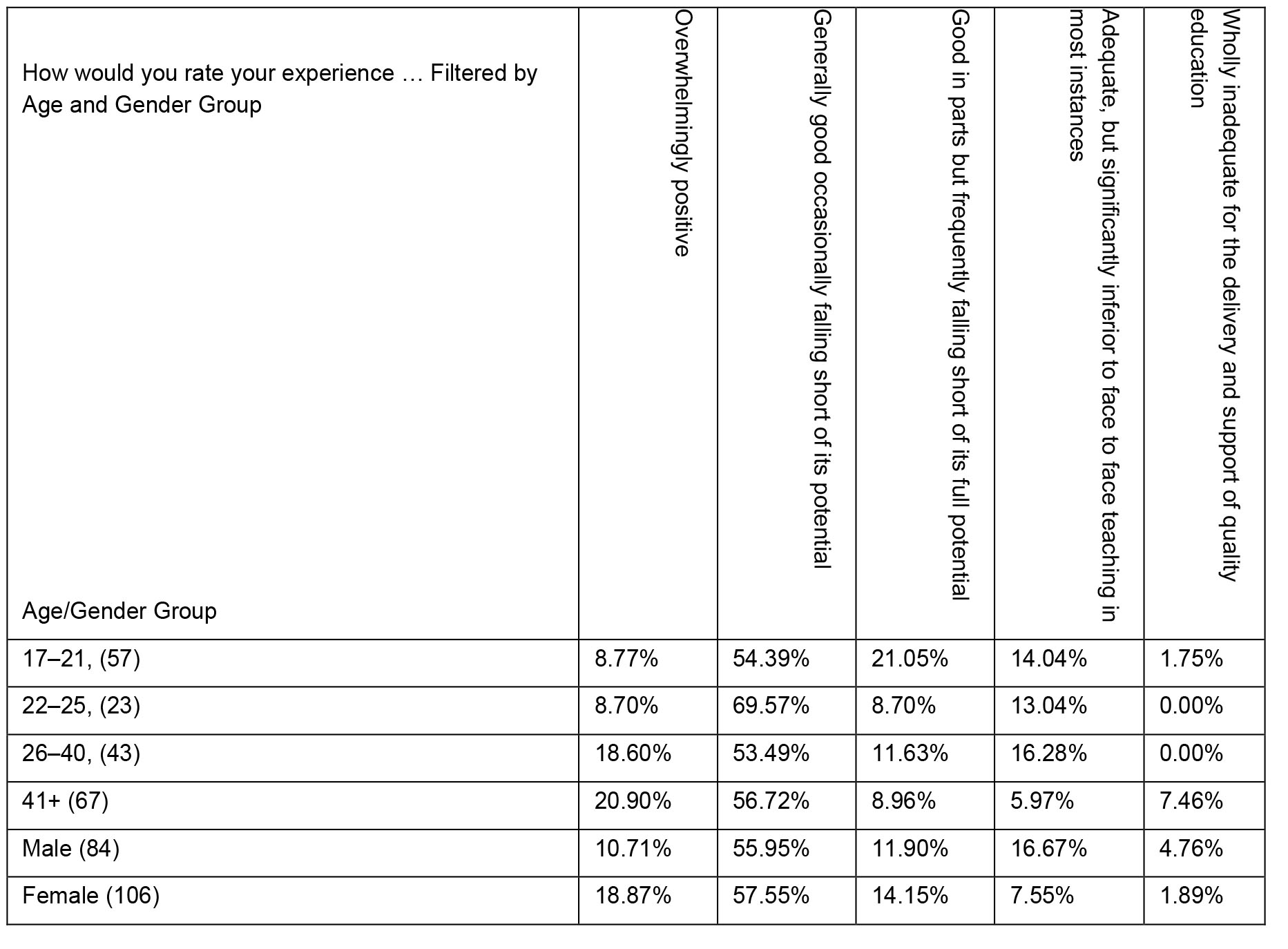

Table 18 Rating of the VC experience filtered by age and gender

Satisfaction varies considerably between different social groups. Women are more likely to rate their experience highly than men, about 10% more selecting the top two categories and about 12% fewer selecting the bottom two categories. It is difficult to speculate on why this should be without resorting to stereotypes. Are women better communicators? The answer seems more likely to lie in social circumstances than biological difference. Women remain society’s principal carers and are also more likely to be tied to an area by a partner’s career. Their expression of satisfaction, therefore, needs to be seen in the context of more limited educational alternatives. The pattern of satisfaction with age is even more divergent than that for gender. The oldest students rate their satisfaction in the top two categories almost 14.5% more frequently than the youngest students. Conversely, they select the lowest two categories about 3.4% less frequently. It is easier to believe that genuine motivational and skill differences have influenced the differences in satisfaction for the different age groups. However, again social context is likely to be at least as important. It is much easier for young people to go away to university as they have, on average, fewer social and financial commitments.

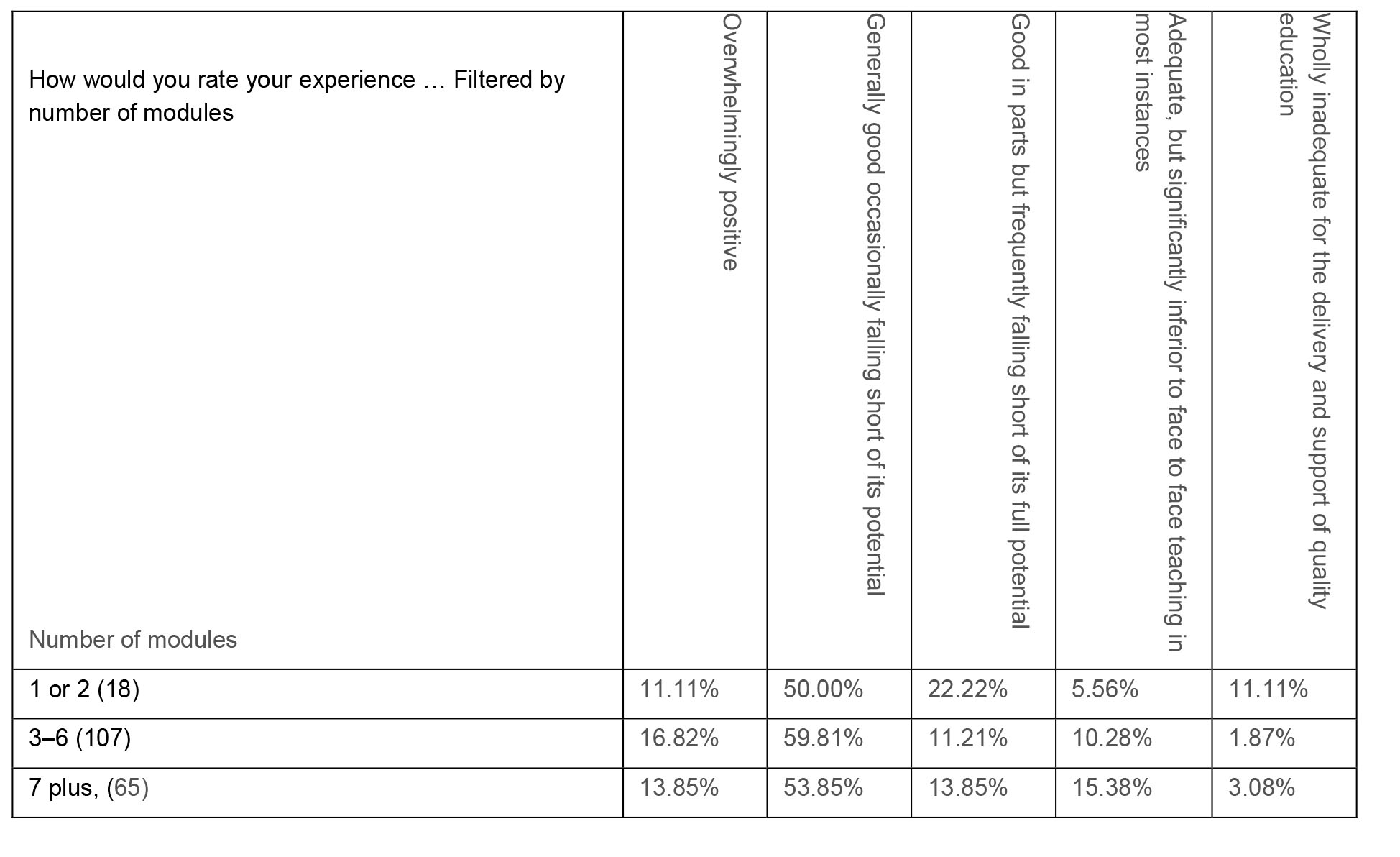

Less than 10% of students in the survey reported taking only one or two modules by VC. The largest group have taken 3 to 6 (56.32%), with those taking seven or more making up the rest (34.21%). As might have been anticipated, those with the least VC experience were the least satisfied, with the largest proportion of students reporting a “wholly inadequate” and the smallest an “overwhelmingly positive” experience. Possibly the skills to thrive in and enjoy the VC environment are steadily acquired as students spend more time in VC sessions. However, this isn’t borne out in the comparison between students with experience of three to six and those with seven plus modules, where, if anything, the more experienced students are less happy. Two alternative explanations seem more plausible for low satisfaction amongst the students with only one or two modules in the VC environment. The first is that those that have a really bad experience are likely to drop out or at least avoid that mode of study in the future. The other is that this group probably disproportionately includes students taking a VC module as an elective from a programme primarily supported by face-to-face teaching. Very likely their induction and support in the use of VC is inferior to those where VC is central to the delivery strategy of the programme as a whole.

Table 19 Rating of the VC experience filtered by number of VC module undertaken

To the question “what most impressed you about modules’ delivery by VC?” the most common response (46 students) was simply that it made access to education possible, either to a remote area or because it allowed delivery directly into their homes. One student was full of praise for remote access “because I had an operation and couldn't return to college for two weeks. I had installed Jabber [at home] and could access even unscheduled classes through VC …. This was so helpful so I wouldn't miss any classes and have to catch up when I returned”. Many of these were glowing endorsements of the VC experience, but clearly students’ attitude was significantly coloured by the availability (or not) of alternative educational opportunity.

For those using videoconferencing to teach, this survey of 190 students from across the spectrum of UHI’s taught HE programmes provides some reassurance that a good learning experience can be routinely delivered. Clues as to how that experience might be improved are provided by the very substantial differences which exist between satisfaction ratings for different reported behaviours and groups of students.

The effectiveness of VC teaching is very strongly influenced by how the VC is managed and the wider educational supports put in place. While previous commentators on VC have often emphasised its role in presenting carefully choreographed lectures (Gill, Parker, & Richardson, 2005), the medium is actually most effective when used for two-way communication, more of a tutorial or seminar, with active student participation (Calodine, 2008, p. 239). VC should never be a stand-alone mode of delivery. The bulk of module content should be displaced to other media, particularly the VLE, which is far more reliable and convenient for students to access (Clarke, 2009). ‘Flipping the classroom’, as it is sometimes termed, (Sams & Bergmann, 2013), frees up time within the VC session for students to be active participants in their own learning, also providing the tutor with crucial information on student engagement and comprehension. Ensuring that everything vital is available within the VLE is also a contingency against technical failure, which is a racing certainty if VC is used extensively and for long enough.

If students are going to participate effectively, everyone needs to see and be seen, hear and be heard (see Figure 4 illustrating the ‘continuous presence’ facility allowing multiple remote sites to be seen). The arrangements of both the hardware and the participants within the VC space are crucial. Because of the importance of eye contact (Bondareva, Meesters, & Bouwhuis, 2006) tutors should think very carefully before attempting to lead a VC class with students alongside them. It is very hard to address the camera and be inclusive of remote students where there is a large local cohort in pole position to seize their tutor’s attention. If students are to be present locally, classrooms need to be ordered so the tutor can address both the remote and local students’ equitably. Nothing could be more calculated to alienate and exclude remote students than to appear focused exclusively on the local class.

An effective VC session requires that all the participants know what they are doing technically and are clear on the etiquette for taking part. Both staff and students need to know the technical basics and where and how to get more advanced help if things go wrong. This study suggests that students who have accessed training, although they may not recognise the association, are far more likely to rate the VC learning experience a success. Students that don’t access training are also a menace to the rest of the VC cohort, joining sessions late, forgetting to use their mute and generally behaving inappropriately. Instruction documents, podcasts and live training sessions currently used by UHI could undoubtedly be improved, but even lower hanging fruit is student uptake, running at just over 52% in this survey. Teaching staff also need training in a mode of delivery which is superficially similar to but actually rather different than face to face teaching (Frindt, 2009, p. 158). They cannot expect to gain their class’s respect and confidence if they themselves would fail the technical and presentational standards the University expects of its undergraduates! Staff, therefore, need to be familiar with their equipment, be very organised in the structure of their teaching and start on time, even if some elements of their virtual class are absent for whatever reason.

Looking at societal groups, mature students are generally more satisfied with their learning experience than younger students, women are more satisfied than men, and participants from very remote places are generally more satisfied than those attending larger campuses. The view that the younger generation are “digital natives” naturally imbued with technical skills and learning preferences is now generally discredited (Bennett, Maton, & Kervin 2008). That men and women possess innate intellectual or social abilities affecting the effectiveness of the VC learning environment seems similarly improbable. Rather than reflecting differences in ability, variability in satisfaction is almost certainly substantially the result of student expectation. Students with fewer alternative options in education would appear from this survey to be more forgiving of the shortcomings of the VC technology, more likely to see the glass as half full rather than half empty. This should have implications for UHI’s marketing strategy – we do best when we reach students not well served by traditional HE providers. Given that both PC-based VC and online library resources have become increasingly effective (Anderson 2008, p. 53), an opportunity exists to reach out to students off campus and well beyond the UHI region.

Simon Clarke is a senior lecturer in archaeology, based in Shetland College. He has been using videoconferencing to support distributed cohorts of students enrolled on networked degree programmes across the University of the Highlands and Islands partnership since 1998.