Chrissi

Nerantzi, Manchester Metropolitan University

Haleh Moravej, Manchester Metropolitan University

Floyd Johnson, Manchester Metropolitan University

LEGO® Serious Play® (LSP) was developed by LEGO® as a tool for other businesses, and LEGO® itself, to revitalise strategic team meetings and find more creative ways for team building, ideas generation and complex problem solving. In the mid-90s, LEGO® experienced big challenges. Digital toy makers presented a real threat to the company (Frick, Tardini, & Cantoni, 2013). A new strategy was needed urgently that would enable LEGO® to survive and thrive in the changing market. LEGO® turned to its own plastic bricks. This strategy helped the company to come up with innovative solutions that led the company from strength to strength. The LSP method emerged and was developed over a number of years. There have been over 20 iterations (Rasmussen, 2006). In 2010, LEGO® decided to make LSP available as open source and the two master LSP facilitators, Robert Rasmussen and Per Kristiansen, who were also involved in the development of LSP, offered training and certification to individuals and groups. This helped the method to spread, increasing its use and popularity across the globe. For many practitioners, it also became a new area for research and inspired them to experiment with LSP. It is recommended that LSP practitioners are trained and certified to maximise effectiveness of the method and the desired outcomes are achieved (The LEGO Group, 2010; James, 2013; Nerantzi & McCusker, 2014).

The literature in this area is still limited, but practitioners are getting together, often using social media, virtual networks and communities as well as face-to-face conferences and events to connect, support each other, share practices and identify opportunities for collaboration.

In more recent years, LSP has found its way into higher education. It is increasingly used in a variety of learning and teaching as well as research contexts (Gauntlett, 2011). These include aiding the development of reflection, creative problem solving and ideas generation; soft skills development; gaining insight into the student experience and creative research method; collecting valuable qualitative data and making the research experience pleasurable and fun. Indeed, LSP creates a relaxed and playful atmosphere and helps individuals and groups open up and share in a non-threatening way and quickly leads to participation for all (Rasmussen, 2006). Personal stories are shared and discussed through LEGO® models using metaphors that lead to new insights and understandings.

The creation of LEGO® models is a process of thinking with our hands and learning through making (Papert & Harel, 1991; Gauntlett, 2011). Models help individuals to externalise their thoughts, feelings, reflections and ideas and provide an insight into complex situations and their internal world (James, 2013; Nerantzi & Despard, 2014; Nerantzi & McCusker, 2014). The mixing of reflection with play, creativity and imagination is what James and Brookfield (2014, p. 55) define as “creative reflection” and can have a powerful impact on learning.

The purpose and the desired outcomes of a potential LSP workshop are discussed in advance with the facilitator. LSP is not the answer for everything and the LSP facilitator needs to decide when it is appropriate and what would be the best way of structuring the workshop. When the basics have been agreed, the LSP facilitator puts the workshop together. This usually consists of an introduction to the method and the underpinning theories, a short LEGO® building warm-up activity and the main part of the workshop, which is a set of LSP tasks that scaffold reflection, sharing, co-creation of knowledge and lead progressively towards achieving the workshop goals. Questions are open ended and short periods of time, usually a few minutes, are given to complete each model-making task. Kits or loose bricks can be used and a smaller amount of bricks will feed the imagination more.

The facilitator asks a series of open questions linked to the goal of the workshop. All participants are invited to build models linked to these using LEGO® bricks, usually in a short timeframe. In LSP, the models are built by individuals and the metaphor is owned by the model maker. There is no right or wrong model or visualisation and it is not about the artistic qualities of a model but what it means and represents to its maker. When all models are made, each participant shares their story and reflections using the model they created with the rest of the group. Participants and the facilitator will ask questions linked to the model if they need further clarification and also make comments if they want to. At the end of the process, participants and the facilitator reflect on the process and what they have learnt through this about themselves and the group.

Today, the pressures of League tables and increased competition among institutions have led to intense measuring and data collection. This happens often through surveys intended to provide an insight into the student experience and enable institutions to evaluate and enhance learning and teaching and position them in a prominent position in the league tables. Surveys at unit and programme level are common. Some internal surveys are closely linked to the National Student Survey. In our reflective analysis we asked ourselves what effect this constant flow of data collection has on students and staff. Can it cause survey fatigue? Porter, Whitcomb and Weitzer (2004, p. 66) claim that the answer to this question is yes. They note that routine multiple surveys and time constraints are cited often as the main causes of non-respondents. Brookfield (1995) reminds us of four reflective lenses (self lens, student lens, peer lens and literature lens) and the need to put all voices into perspective. Could it be possible that we over-emphasise the student voice as expressed through student surveys and perhaps neglect other ways to engage in dialogue with students but also take our own reflections, those of colleagues and those expressed through the literature into consideration? We attempt to respond to these questions in this paper through reflection.

If researchers are interested in using survey instruments on top of routine surveys, they should be aware of how students feel about surveys more generally and consider using alternative, perhaps more participatory and creative, ways to evaluate their teaching that will help students open up and create genuine opportunities for dialogue.

LSP might provide a valuable alternative solution to surveys and other more traditional and commonly used evaluation strategies. According to Kristiansen and Rasmussen (2014, p. 215), “building the intangible into physical models, and articulating and visualizing data can help us see what we may otherwise be missing, and find the surprising patterns.” Gauntlett (2007) also refers to the power of metaphors and making, and the impact this has on individuals to externalise inner thoughts and ideas. Gauntlett has employed such strategies with great success using LSP among other methods to carry out social research.

Using LSP for qualitative evaluation of the student experience is an approach worth exploring based on the above rationale which the authors wanted to trial. An LSP workshop was developed using an appreciative enquiry approach to frame the questions and activities. It was offered to first year undergraduate students to evaluate a specific unit from their perspective based on their experience.

Author 2 created a new unit for the campus-based Nutritional Sciences course called Nutrition 21. This was offered for the first time during the academic year 2013/14.The unit is a first year unit and introduces students to social, sustainability, psychological, physiological and cultural aspects of food in the 21st century. The unit is evaluated by two sets of internal surveys in term one and two. These are set by the University and carried out centrally. Students complete the survey anonymously via Moodle, the institutional Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). The surveys seem to focus more on ‘enjoyment’ and what students ‘like’ and less on learning and learning gains as a result of participating in a particular unit or programme of study.

As a creative practitioner, Author 1 is open to new and creative ideas that will enhance the student experiences. She was interested in LSP as she was searching for ways to gain a deeper insight into the student experience that could help her make improvements to the unit and collect data that would enable her to do so.

The LSP session was the last timetabled session of the second term. Students knew in advance that an external facilitator would be working with them. The exact plan was communicated to the students at the start of the session. The facilitator secured students’ consent to take still and moving images which provided valuable additional research data. The facilitator would lead the session to discuss their experience on this unit in a participatory and playful way while the unit tutor would act as an observer and was invited to take notes throughout.

What follows are three authentic narratives of the authors who had different roles in this evaluation workshop: the LSP facilitator (Author 1), the unit tutor (Author 2) and one of the students who participated in the LSP workshop (Author 3). It was organised to gain an insight into the student experience linked to the Nutrition 21 unit. Their individual and collective reflections provide an insight into how the workshop was experienced and the value it had for the individuals as well as the group of students.

The purpose of the LSP evaluation workshop was to find out if we could engage a tutorial class of 1st year undergraduate students in a unit evaluation process linked to Nutrition 21 using a pan-participatory, qualitative and playful approach beyond paper or digital surveys or even interviews or focus groups.

Our focus was on identifying what helps Haleh's students learn and less about how satisfied they are from a consumer point of view. This is perhaps where we divorce ourselves from some of the surveys that are around and used more widely. I am using the term 'consumer' here to create a contrast in my thoughts but also to highlight that the focus of our investigation was student learning, students' conceptions of learning and their thoughts around what they felt helped or hindered their learning in a specific unit. We were also interested in their ideas to make learning happen more effectively and naturally for future cohorts of students on this unit. So students in this context were taking more the role of collaborator and co-designer for their own learning.

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato said: "We learn more about a person in an hour of play, than in a year of conversation" – could this be true?

We played for two hours! Just imagine how much we learned about each other!!!

We wanted to gain a deeper insight into the student experience of a whole group on the unit and find out how students felt the unit could be enhanced for the next cohort. We wanted to do this in a relaxed atmosphere that would foster opening up reflection and self- and collective discovery through making and sharing.

We decided to use the LEGO® Serious Play® (LSP) method. I have used LSP before in different learning and teaching contexts with students and teachers and also in conference workshops and have found it a useful method to make individuals and teams feel more relaxed and engage in something that is playful and unusual while also having a pedagogical value that helps individuals deepen their reflection. It also seems to increase their critical and creative thinking capacity and connect them and their ideas and thoughts with others.

I was really pleased that Haleh embraced this playful approach with passion when I suggested this during a chat we had about her new unit and she shared with me that she was looking for a meaningful way to evaluate the unit with her students. As Haleh and her students were willing to give LSP a go, nothing could stop us!

LSP is thinking with our hands, a series of activities through which we create models or visual metaphors of our internal world made out of LEGO® bricks triggered by a specific question that makes us reflect, think and build meaning through actually building a real model. We could say that LSP is a process to open up and externalise thoughts, ideas, beliefs and fears and other stuff and share with others creating opportunities for dialogue, further reflection and learning, individual and collective.

It was fascinating what we experienced and I think the students were also surprised with themselves and what they disclosed and shared with their peers about themselves. I could see it in their eyes. I could hear it in their voice. I could see it in their body language. Some might have been sceptical, at least at the start, but this is fine. It is healthy to be critical and think about what we are asked to do and what the value of this would be for us. I think it did help explaining why we choose LSP, what we could achieve and how, as well as saying a tiny bit about the underpinning theories behind it. In a way, this takes part of the magic away, I suppose, but the real discovery comes when actually experiencing LSP in action. And there were definitely some light bulb moments for all of us...

What happened? Desks and chairs got in the way. We decided to sit on the floor and created a magical circle (see Figure 1). After the LEGO® warm-up activity, students were asked to reflect on their learning on the unit and create a model that would capture what learning on the unit looked like for them and mark with a green brick what worked and with a red brick something that didn't work so well for them. During the second part of the session students were asked to think about what learning would look like on the unit if everything would be ideal. They did this initially individually but then connected their ideas in sub-groups and shared with the whole class. It was fascinating! All students highlighted very similar things as important factors to make learning happen. Haleh was taking notes throughout and responded at the end of the session, which brought everything together.

Figure 1 LSP evaluation workshop in full flow

Students were really focused during the making stages and Haleh was surprised as this group is usually very vocal. Students were concentrating and connecting their thoughts while making their models. I really loved that we were all sitting on the floor, around our LEGO® campfire, and ideas and thoughts emerged, took shape and were shared. Students showed interest in each other's stories and were asking questions and commented on each other’s thoughts. Students opened up really quickly. I think it did help that the group knew each other and they felt safe perhaps.

I was impressed with the maturity of students and their commitment to learn and become professionals in their chosen area but also that they acknowledged their need for support and guidance from their peers and tutors to achieve their goals. Their stories provided rich evidence for all this.

After students shared their ideas about their ideal experience on this unit while Haleh was quietly taking notes of the stories students shared (I think she filled loads of papers and was not participating in any of the activities), Haleh shared her first thoughts in response to what her own students had said in the last two hours and what her first thoughts and ideas were to tailor learning and teaching on this unit further to help future students. I loved the openness and the transparency of the whole process. Students and the tutor showed enormous respect for each other and were really interested to find solutions that would work for all.

I was extremely excited to gain an opportunity to work with Chrissi from the Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT). I had discussed the evaluation of the Nutrition 21 unit using my tutor group and a creative method. When Chrissi told me about LSP, which was new to me, I instantly said ‘yes’ as I saw the potential that this playful method might be an antidote to the surveys normally used and provide a different kind of information to me about my students and their learning experience.

We arranged the session on the Tuesday at the end of term, 4–6pm (sometimes a very challenging time to keep students motivated after a long day at university). I was asked to observe and stay quiet while Chrissi was facilitating. It was really hard for me not to speak, especially as I like to communicate with my students and foster dialogue and conversation. This time, this was done by Chrissi.

The students walked into the room all excited as the chairs and tables were pushed back and the floor was chosen to bring us back to earth and what it means to go back to our ancestors and sit around a fire and talk!

The session started with Chrissi asking the students to build a tower with what they had in their bags and share how they learn. Their comments were a great reminder that we all learn in different ways and that we are in fact all unique. I am now thinking that it would have been useful to know all these things at the start of a unit so that I can help my students in their learning but also help them develop more effective learning strategies. Organising a bespoke workshop to gain that insight would be really valuable. Some of the comments I noted on my piece of paper are:

As the workshops progressed, it was extremely interesting for me to hear my students’ stories and how they opened up about their learning experience. When the question of “How could the unit change so that it is more effective for your learning” came up, the students made interesting points using the LEGO® models they created. I felt really proud and a bit emotional. Comments included:

Reflecting on using LSP to evaluate the unit, I have to say that it was a refreshing process. It somehow made me, the lecturer, invisible and enabled me to observe my own students and actively listen to their experiences and stories. I think using LSP to evaluate a unit made the students understand better the role they play in their own learning. Through their stories they revealed that they now have realised that learning is not a one-way street of receiving information from the lecturer but that they play an essential role in their own way of learning and appreciate each other’s uniqueness that does enrich their own learning experience individually and collectively.

I have always been aware and celebrated the way my students are different but never had a chance to study them all like pieces of a chess board. The LSP evaluation showed me that somehow, if I make an effort to understand them right from the start, I will be able to see how they strategically all fit together to create a better learning experience for each other and support them in their own learning. It becomes us learning with and from each other.

“Instruction begins when you, the teacher, learn from the learner. Put yourself in his place so that you may understand what he learns and the way he understands it.” (Kierkegaard, unknown)

LSP made me more aware of students’ individuality and their collective identity. The LEGO® models helped my students to visualise their thoughts and ideas about optimum conditions for meaningful learning. LEGO® Serious Play® was not serious. From the body language, smiles and giggles after long, deep reflective silences during the model creation phase, which I could see were essential part of this process, students demonstrated that they were really engaged in the process, were interested about their studies, curious and wanting to learn.

My final thoughts linked to the LSP workshop and the method itself:

I wrote the following after the LSP workshop and shared with my tutor and the LSP facilitator: We did some LEGO® play yesterday and we now know each other much better. I realise that currently the tutors change each year, but we don't want to start from scratch with somebody else and a new group (as we know each other so well after our LEGO® therapy) when we already have such a strong bond with Haleh who is so creative and has been supporting us personally and academically. We have all built a really strong relationship both with Haleh and each other, and feel like it would be a shame to lose the dynamic and foundation we have built together." (Used here with Floyd's permission)

A few months later, I reflected in more detail about this experience:

The LEGO® Serious Play® (LSP) workshop engaged everyone from the moment we walked into the room. It was clear that the group was going to have a new experience and the playful element of LEGO® made that completely non-threatening. It was something different that engaged everyone and required a deeper level of contemplation than conventional forms of feedback. Feedback forms often follow multiple-choice formats, which only offers a very narrow opportunity for the student to evaluate their experiences. LSP offered a feedback route that was creative and completely open to evaluating any aspect of the learning experience.

The lack of any warning made sure that what was expressed was fresh, not overthought or designed to suit the format; the feedback was not influenced by others. LSP was not introduced as a concept. On the contrary, understanding was developed progressively and emerged through engagement. Arriving, expecting a seminar session as usual, the group initially noticed that all of the tables were around the room and we were told that we should put our belongings to the side of the room and sit in a circle. Chrissi then gave the group a short briefing about the session being about feedback, using LEGO® as a way to express our thoughts and feelings around certain aspects of the unit. Our Lecturer would remain unusually and unnervingly quiet.

The familiar, playful and simplistic form of LEGO® was why many of the group (who did not identify as being creative or confident) felt so comfortable with using it as a prop to express their thoughts and feelings. The group focused more on the feedback as a whole reflective process rather than being distracted by answering set questions.

The versatility of using LEGO® as a sculptural medium allowed the group to create something that reflected the various aspects of our learning. It was effective not only in allowing us to provide feedback on the unit but in triggering us to reflect on each of our roles in our learning (and the ways which worked best for us). It was more effective than filling in a feedback form or questionnaire (which always use the same, stale stock of questions and treat the student as a passive observer in their learning rather than a participant or collaborator).

Each student was asked questions about how the unit worked for them and how they personally interacted with the subject matter. Chrissi’s questions demanded a considered and insightful response from the students. She was clearly engaging with what everyone was saying and was able to pick up on themes coming from the feedback. It was an outlet for some reflections I already had,but enabled me to further develop my opinions and ideas. Chrissi’s questioning started with individual feedback and this led to a larger scale, group collaborative in the feedback of the Unit, reaching some common themes. At one stage, Chrissi requested that we reverse the process of sculpting, and build first, interpret later. This provided a catalyst for questioning and evaluating our thoughts and feelings to an even deeper level than what may have occurred to us naturally.

Many of the students commented on how much they learnt about themselves as well as each other. This provided a new opportunity to be more mindful of how one and each other learn differently and how we can adapt our approaches accordingly.

This led the group to consider how LSP may be particularly useful as a group bonding exercise at the beginning of term or new units.

LSP was genuinely stimulating, engaging and insightful. It increased the group’s bond and built the group's understanding of each other, improving the dynamic. LSP provided the perfect environment for sharing feedback in a way that was both mindful and effective. The group left with a sense that learning would be a little easier from then on.

What follows is a synthesis of the student voice captured during this specific LSP evaluation workshop. It provided food for thought for the unit tutor and will help shape provision in the next academic year.

It became apparent that these students love variety and that they get bored when they just have to sit there and listen to stuff. They switch off. While students want to interact with other students and learn together, they also want time for themselves and opportunities to learn on their own. When asked to learn something, students want to understand the usefulness of what they are learning, how it all fits together – the bigger picture. They can’t always see it and often feel overwhelmed or distracted, also by their own technology. While students love to learn through visuals, they also understand the value of reading. However, they want to be actively involved in the learning process and engage in authentic activities. This seems to be very important to them! They expressed a preference for learning through application, experience and practice to develop theory instead of the other way around. Students also highlighted the need for their lecturers to have a passion for their subject and inspire them. The key confirmation was that students want to learn and they need help and support from their tutors and peers.

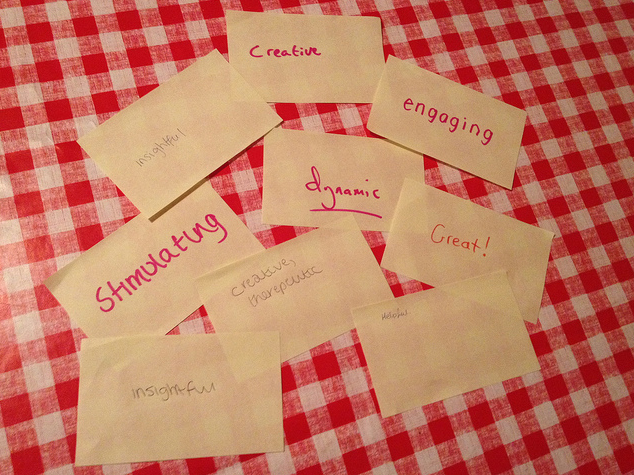

Students engaged in the LSP evaluation session and found it valuable. Feedback collected at the end of the process through post-it notes confirms this (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Post-it notes with student feedback about the LSP workshop

Students noted that it helped them share inner thoughts and ideas but also found out about how their peers felt about learning on the unit and how they could move forward together. Reflections shared by the student and teacher, confirm this. Some suggested that a similar LSP activity would have been useful at the start of the academic year and I can see the value of doing this to speed up the process of opening up and create learning relationships and community.

The first year students spent two hours together during the LSP workshop and the facilitator recognised their desire to learn as expressed through their models and stories. They were motivated and cared for each other, they felt that they were belonging to a learning community and wanted to succeed in life and become excellent professionals in their chosen field. They recognised the important role of the teacher as a facilitator and supporter of their learning but also as somebody who is inspirational and a role model. Their stories, our observations and reflections showed that they want to be in a state of being switched on. How can we educators help them to reach this stage?

Could we have got these positive results from a survey, an interview, a focus group or using another way to collect data? I think we could, to some extent. Perhaps we wouldn't get the richness of responses and we definitely wouldn't be able to create the atmosphere for opening up and sharing and creating opportunities for peer bonding and a sense of community which happened naturally, without being forced, and created new opportunities for peer-to-peer connections and learning.

Learning relationships are important for learning and can be powerful motivators. Would a survey, an interview or focus group have achieved what was achieved in two hours of play with LEGO®? Further research in this area, including comparative studies, is required to come to specific conclusions around this.

However, looking back at the remaining questions which we attempted to answer through reflection, we can clearly see that LSP and the process of writing about this particular activity provided a valuable opportunity to apply Brookfield’s (1995) four reflective lenses in a hands-on, participatory and playful way. We not only gained new insights into the student experience of this particular group but were also able to connect this with the tutor experience and turn module evaluation into a dialogic progress while closing the feedback loop quickly and in a future-facing way.

The authentic stories shared here and observational data collected during the session helped us articulate the following: Using LSP combined with an appreciative enquiry approach as a mechanism to evaluate a unit was effective and created opportunities for an open, transparent and constructive exchange through which an insight into how students experienced a specific unit was gained. Communicating this to each other, their tutor and the facilitator using the models created with LEGO® bricks and deep reflection on these was seen as valuable for all who participated in this process. The familiarity of the LEGO® bricks themselves made students feel at ease and confident that they would be able to convey their message through a model. Individuals felt safe, opening-up and making connections with their inner selves and each other. Students got to know their peers and strengthened relationships and developed a stronger sense of individual and collective identity. The tutor gained a deep insight into the student experience, who her students were. The whole process enabled her to reflect on her practice and identify opportunities to further enhance the Nutrition 21 unit based on students’ contributions, which was discussed with the students at the end of the session. It was a wonderful moment, which evidenced active listening and partnership working and enabled closure of the feedback loop and commitment to action.

It was suggested by Author 2 and Author 3 that LSP could be used at the start of a unit as this would help students and the tutor to open up much earlier as the details shared, individually and collectively, were thought to be important for shaping learning experiences.

This specific example shared here is encouraging and invited further investigation. It is our intention to use the LSP approach developed for Nutrition 21 for further unit evaluations and engage in related research activities to come to more precise conclusions about its effect on students and the role they can play in unit and programme evaluations more widely. Furthermore, Authors 1 and 2 have worked together in the academic year 2014/15 and offered an LSP workshop to Nutrition 21 students to build peer and tutor relationships early on in their unit. This was a direct result of the success the LSP evaluation workshop presented here had and lessons learnt from this.

We would like to thank the Nutrition 21 seminar students from Haleh’s tutorial group, who willingly and openly participated in the LSP evaluation workshop, and their insightful comments. Additional thanks go to Dr Alison James for reading the draft and her valuable suggestions.

Chrissi Nerantzi is a Principal Lecturer in Academic CPD at MMU. Her approach is playful and experimental. She specialises in creative and open learning & teaching. Chrissi is an accredited LEGO® Serious Play® Facilitator, a Senior Fellow of the HEA, a Fellow of SEDA and a National Teaching Fellow. For further details, please access http://uk.linkedin.com/in/chrissinerantzi

Email: c.nerantzi@mmu.ac.uk

Haleh Moravej is a Senior Lecturer in Nutritional Sciences at MMU. She is a nutrition entrepreneur and a creative educator. Haleh is a senior food consultant working with the food industry. Haleh is the founder of MetMunch, a social enterprise bringing community, employability and sustainability together. Haleh has won numerous awards, among them the prestigious International Green Gown Award for Student Engagement.

Email: h.moravej@mmu.ac.uk

Floyd Johnson is a second year undergraduate Nutritional Science student at Manchester Metropolitan University. He is actively involved in MetMunch public engagement projects and believes that reconnection and empowerment within the kitchen is key to reducing the environmental impact of food production.

Email: Floyd.johnson@stu.mmu.ac.uk