Dr Narelle

Lemon, La Trobe University

Megan

McPherson, Monash University; La Trobe University

Dr Kylie Budge,

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences

Social media is now a significant issue in the academy because of the ways it is being used by academics. Academics are using social media in a variety of visible and public ways that may conflict with social media policies and their place, values and behavioural expectations of the university. In this paper, we focus on why academics and scholars employed within a variety of international universities think that they use the social media platform of Twitter. We discuss preliminary findings from a small study of academics and scholars using Twitter and draw on ethnographic methodology in order to show that there are many reasons why they participate professionally in this medium. This multitude of reasons conflates simple readings of what role Twitter plays in their connected lives, identity, and their academic agency within the academy. Using snowball selection techniques of participants has meant that they are linked in some way to the researchers. As researchers, we see their tweets and we ‘know’ them by what they tweet. This is in contrast to the semi-formal interviews where participants discussed and shared thoughts, ideas and experience. Our academic colleagues gave us their insights about the ways that they use Twitter, which in turn informs this research and our own practices. We are thinking about the social practices of academics in order to examine how the notion of being an academic and the ways in which localised discipline repertoires (Trowler, Saunders, & Bamber, 2012) are challenged by the visibility of social academic practice on social media. Influential networks, interconnectivity and visible networks are informing this stance.

In this paper, we explore the early analysis of the findings that shows that there are a variety of interconnected reasons why academics used Twitter. Our interviewed participants discussed a range of issues and we have themed some of these as: transforming academia; new identities; networks; changing in enacting scholarly work; communication; ways of use; academic identity; branding; engagement and reflective/reflexive practice; inquiry; and (non) strategic. We concentrate on the emerging themes of branding and the use of strategy (or not) that are transforming ways of being an academic in the current contemporary context. In focusing on branding and the realising of a need to brand, or distinguish, one’s self in a way that is outside one particular institution and more holistically within a field or group of fields, the reflexive nature of what and how academics are doing this is explored. We do this to give a rich textual reading of the data contextualising this discussion in our connected lives, identity and academic agency. We argue that Twitter is a powerful connection between networks of academics that adds elements of porosity to academic life. It entangles academic disciplines together in unforeseen ways. For the individual academic, the multiple roles of being and becoming researcher, educator and academic administrator allowed by Twitter enable a different view of what an academic life is in the contemporary university. We conclude by suggesting that social media play a role in the university as a space for the influential building of academic networks that enable different kinds of academics to become. The significance of this research is that we investigate the role of Twitter in a small network of academics documenting their views of their experiences rather than quantitatively looking at how they actually use Twitter, how they tweet, who they favourite and retweet. It gives a different way of attending to the notions of connected lives, identity and academic agency within the contemporary academy that in turn expands how we describe what we do in social media as academics.

Throughout this paper, we explore ways of being an academic – that is, the public, visible, connected and networked academic – by asking the research question: Are academics, by participating in the use of social media sites such as Twitter, transforming what it means to be an academic? We position Twitter as a platform that enables a way of doing/being and becoming an academic. We consider the notion of branding: what does it mean to brand what we do as academics? And in what ways does the use of profile texts and images operate? We then move into notions of the strategic and acknowledge where people see they have to shift. Some are conscious and some are unconscious about what they think they have to do to fit in or not fit into this context.

Since the emergence of Twitter in 2006, those working in higher education institutions have been using it to communicate, network and share information extending from and about their various ideas and academic practices (Pearce, Weller, Scanlon, & Kinsley, 2010). In more recent years, as curiosity and confidence about the technology have grown, the number of academics using Twitter has expanded to an estimated one in forty active scholars in universities (Priem, Costello, & Dzuba, 2012). Further to this, Twitter reports that “out of the 1/2 billion tweets that post every day, 4.2 million are related to education” (Stevens, 2014, para 1). This participation has led to growing contributions regarding how to engage professionally with this form of social media, for example, ‘how to’ guides (Mollett, Moran, & Dunleavy, 2011), and understanding the basics of how Twitter works in conversation terms (boyd, Golder, & Lotan, 2010). How to publish and disseminate research (Pearce et al., 2010) is another aspect as to how academics use Twitter for pedagogical purposes, especially with their students, and the benefits that result from such innovations (Junco, Heiberger, & Loken, 2011; Lemon, 2013; Lemon, 2014; Pestridge, 2013; Rinaldo, Tapp, & Laverie, 2011). As Weller (2011) reiterates, Twitter use by academics highlights changes in scholarly practice. Thus, it contributes to ongoing discussions on how Twitter can and could provide a powerful addition to the professional practices of academics and demonstrates, as Marshall McLuhan (1960) coined, that the medium is the message. We are all looking for new ways to engage and interact (Weller, 2011; Lang & Lemon, 2014). This is particularly relevant in times when new ways of working (Lupton, 2014; McKenna & Hughes, 2013) and “ways of utilising technology in the online space are challenging how academics and students communicate, participate, and publish in modern universities, and thereby influence knowledge production, exchange, and transfer” (Lang & Lemon, 2014, p. 112).

To date, the largest study on academics and their use of Twitter has been conducted by Fransman (2013) and her colleagues at the Open University in the UK. In this study, Fransman used a macro lens to explore and understand academics’ Twitter usage (and non-usage). She highlighted a number of findings about the ways in which academics interact with Twitter (or not). Specifically, Fransman concluded “that developing a strong ‘digital footprint’... enhance[d] an individual’s influence in academic networks” (p. 33), that use of Twitter is linked to “strong ‘digital scholarship’ practices and better networking” (p. 34), that Twitter use is “distinctly social” (p. 35), and that confidence in this social realm develops over time.

New open scholarly behaviour is enabled by the uptake of new technologies (Pearce et al., 2010). Our study builds from this philosophy and is significant as it addresses a gap in the small amount of research on why academics microblog (Twitter is a social media platform known as microblogging – that is, sharing small elements of content such as short sentences; in the case of Twitter, this is up to 140 characters) and begins to provide evidence as to usage (and non-usage) through the medium of Twitter. Fransman’s (2013) research into academic literacy practices around Twitter provides a useful springboard and positioning for our inquiry. Our study, however, is interested in a more micro-level, personalised experience of using Twitter. We aim to illuminate at a detailed level how academics came to Twitter, engaged and learned from it, while continuing to evolve their identities as scholars.

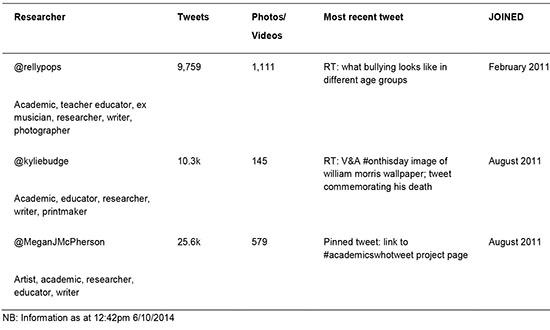

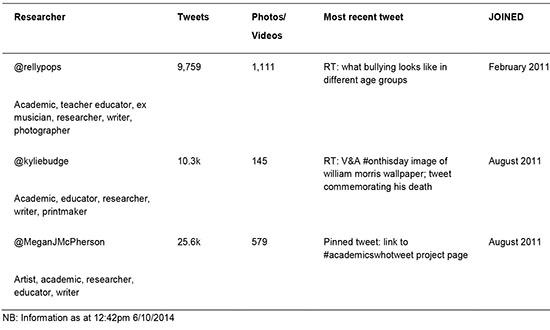

In order to position this paper, we briefly share our context of using Twitter as academics. We came together as three individual researchers finding their way in academia. We have different roles and responsibilities but are united by similar ways of thinking and being. One uniting feature of our collaboration was the use of Twitter to professionally engage with research and to shape and inform our sense of being in the academy. We had all joined Twitter at different stages, coincidentally located at the same institution, but only Kylie and Megan knew each other personally. Through Twitter, we discovered we had a common interest in arts pedagogies and were seeking supportive ways of being as we negotiated our roles. Quickly we developed our relationship through Twitter, and use it now to maintain a connection. We each use Twitter in different ways (see Table 1), leading us to asking the questions: What are others doing? How do social media influence ways of being in academia?

Table 1 Our profiles and examples of our Twitter activity

We are attending to this online space and way of being and doing because of the use of Twitter in our academic lives. The research questions have developed from our own use of Twitter as individuals and as a collective, leading us to investigate a wider sample of peers. By following academics active on Twitter and engaging with them professionally our links expanded outwards. Our interactions enabled us to use a modified snowball recruitment method (Atkinson & Flint, n.d; Mewburn & Thomson, 2013) using our Twitter accounts to begin the process. This enabled us to find connected Twitter users and assisted us to quickly build up a participant sample of 34, through the notion of data saturation, with a breakdown of 35% males and 65% female (see Table 2).

Table 2 List of participants (by pseudonym), their role in academia, location and period that they joined Twitter for professional engagement

We designed this project using a qualitative methodology to enable us to investigate the complexities of life and living, to explore people and social processes and capture the rich experiences held within these (Mason, 2011; Denzin & Lincoln, 2008). (You can read more about the methodology on http://www.meganmcpherson.com.au/awt_projects.html or http://chatwithrellypops.wordpress.com/academic-who-tweet-2014-2015/). The principal method for data collection was semi-structured, one-to-one interviews with participants (n=34), that is academics and scholars (we now refer to academics and scholars as academics throughout the paper) who use Twitter, to explore questions pertaining to the overarching research question: Are academics, by participating in the use of social media sites such as Twitter, transforming what it means to be an academic? The guiding sub-questions include:

a) Does using Twitter

enable the development of more intimate networks?

b) How was enacting scholarly work changed with use of Twitter?

c) Why might academics in higher education use the microblogging site Twitter

to communicate and to what end?

d) What ways do they use this particular form of social media, unique in its

brevity, to communicate with others?

e) How does this engagement contribute to their developing identities as

scholars?

f) How do academics enact Marwick and boyd’s (2011) and Pearce et al.’s

(2010) notions of ‘branding’?

g) Does participating in the online community of Twitter support

reflexive/reflective practice of making academic work and academic identities

less “messy” (Mewburn & Thomson, 2013)?

The majority of participants were interviewed by a research assistant, and in the case of two interviews, by one of the researchers. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, by phone or via video technology such as Skype. If an interview was not possible due to logistical reasons, data were generated by asking participants to provide a written response to the interview questions. Following this, interviews were transcribed.

Data generated through the project have been analysed using a thematic approach. We have explored data for patterns and relationships, to “find explanations for what is observed” (Boeije, 2010, p. 76) through segmenting and reassembling. We coded and themed transcript data using a combination of inductive and deductive approaches guided by literature and our own personal use of Twitter as academics. We approached analysis by “ask[ing] questions of the data” (Neuman, 2000, p. 420; Richards, 2010) and were guided by the research questions, purpose and overall design (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996).

In asking academics about what they do on Twitter, we gathered information about what they think they are doing. These data constitute reflections and memories of practices. In talking about what they do on Twitter, academics are labelling themselves as academics, researchers, and educators in their profiles (see, for example, Table 2). In the interviews, we asked about how participants use Twitter and how this assisted them in working within higher education. We asked about how their profile descriptions and images were developed and how these operated in this online space. Some participants discussed how they labelled their practices in the space in the terms of researcher, academic, scholar and educator. Others spoke about how they used the platform in different ways to do this branding or ‘signalling’.

From our analysis of the interview transcripts, we identified that some academics saw their activities on Twitter as:

In engaging professionally with Twitter, some named their university (Lupton, 2014) in their Twitter profile. This was mentioned by some as promoting their university and as seeing the work they do as being ambassadorial. Others who had removed their university from their profile commented on the policies that had been developed in the university and the way in which this impacted their decision.

After we had an awareness survey sent by the university saying “Do you know that if you’re on social media, even for personal reasons, you have to be adhering to the [university name] policies ... I went “I’m not comfortable with you trying to censor my personal life so I’ll just take the name of my employer off my Twitter account and my Facebook account. Which is a shame because I think I’m actually quite a good ambassador for my university, but I can’t promise not to make the occasional salacious comment late at night… or even during the day. So I’ve made a conscious decision to actually take my employer’s name off there. (Elisa)

Participants reflected upon the types of images used in their Twitter profile. A pattern emerged in how they described the way they wanted to represent themselves. Some changed images regularly, some shifted the image from a self-portrait to other images (for example animals, landscapes, and special places that evoke memories for them) as well as recognising the need to show personality. Some thought the use of a self-portrait allowed people to recognise them and make connections at conferences. Others swapped between images and noticed that they received comments from others about gender in relation to how and what they were tweeting. Some masked their gender using abstracted images or non-gender specific handles (usernames) to counter this issue, interpreting this as a way of forestalling judgement about personal appearances. This multitude of reasons conflates simple readings of the role Twitter plays in the participants’ connected lives, multiple aspects of their identity and what they see as their academic agency within and outside the academy.

The use of profiles prompts thinking about how and why academics want to brand themselves outside the institution. Academics use Twitter as a visual way to represent themselves to a wider audience. Demonstrating different ways of being an academic speaks to the super complex world of academia (Barnett, 2000), where “multiple frameworks of understanding, action and self identity” (Lea & Callaghan, 2012) are at play.

That’s an avatar I’ve had for probably six years, so it’s a bit out of date chronologically. It was one that I had when I was a PhD student and it had been part of my online profile for quite a long time. It’s on my departmental website, it’s on my LinkedIn, it’s on all of my sites. It’s become a brand almost. (Elisa)

How participants discussed their Twitter use and the ways they represented themselves on Twitter talks about the ways they are developing and are maintaining their academic identities. Ways of being an academic were contributed to and informed by how participants thought of themselves as using Twitter. We looked at the data for where participants indicated shifts in the ways they thought they acted or thought that their representations of themselves had changed. Some of the participants had very concrete instances of where they thought they changed their behaviour.

Participants like Conrad changed their profile descriptions and images as they moved through being a PhD candidate and lecturer and later graduating and wanting to make ongoing connections with potential research collaborators. Not only was his profile representation modified but also the ways that Conrad used Twitter on a day-to-day practice. Conrad discussed how he followed and commented on a tweet by a leading scholar in his field and modified his tweeting to be more focused on his discipline area to woo a connection:

Subsequently… I made sure that most of the tweets that came out on my timeline were really [discipline] related tweets, and that ended up in him following back. It took about a week or so, but I made sure that I entered in – for that little period of time, I made sure that I entered into that conversation that he was having, and it was very much a professional conversation about [discipline]... I’m connected there, and I wouldn’t feel uncomfortable now about moving that connection to the next level by emailing him and saying “You know what? The stuff that you’re doing is really interesting and I really like it, and it’s useful for my class but I also find your research really interesting. Let’s chat.” Otherwise I would have to cold call this guy, and he doesn’t know who I am or why would he bother talking to me… (Conrad)

How careers were developed and maintained in the academy was discussed in the ways that participants moderated the way they connected their profiles to a university. Nicole had just moved into the consulting sector after a long career in academia. She discussed how she had moderated the representation of herself in her Twitter profile. A type of academic who connects was how she saw herself now.

I think initially it was much more about the work that I did. Initially when I set it up it was very much “I’m an [discipline professional] working in higher ed”. Now it’s shifted in terms of it doesn’t actually describe my profession but it describes my interests more than that. Now it says I’m a networked learner. I think it still has [discipline professional] but since I don’t do that at a particular place any more it’s more like an idea about who I am rather than this is my job title. It used to be very much this is my job title, now it’s more if you’re connecting with me you’re connecting with this type of person. (Nicole)

Seeing how others use Twitter was also a prompt to think about how they positioned their Twitter account. For example, Rochelle identified her Twitter account as a professional account. Her interactions were carefully considered. She discussed how she sought out colleagues localised in relation to her work as an academic at her university.

The main thing is being busy. I can’t really understand how prolific users of Twitter [other Twitter user]...I don’t understand how [they] can be so prolific and get a lot of work done. I don’t work like that, I need to work on something uninterrupted. I find Twitter is quite distracting. Yes, I would say that it has dropped off, my use of Twitter. (Rochelle)

Rochelle recognised what she thought was a successful way of being an academic, that is, as someone who was connecting prolifically, and expressed her anxiety about how one might find the time to make this a regularised practice. She saw Twitter as a distraction to work and not as part of her work as a connected academic.

The participants’ shifts in ways of being or thinking about how to represent themselves as academics and/or scholars are of interest to our study. This triggers thinking about what the practices of being academic in the university might constitute. In particular, our interest lies in the university as a site of practices – wooing others into a connection, connecting and/or seeing this way of working but not being able to quite understand how this happens. This is all about shifting conceptions of what an academic is, that is, developing and maintaining connections (Bain, 2005) that support ways of being, prompting different thinking about the ways of being, and being visible in the ways that these connections are being networked.

If participants’ use of Twitter was strategic or not (Fransman, 2013) was a theme contained within the data and was elaborated on by some participants. This way of (non) strategic thinking illuminated different ways of being an academic in the current climate of higher education (boyd et al., 2010; Lupton, 2014; McKenna & Hughes, 2013; Weller, 2011). The following four quotes demonstrate dominant themes that emerged from the data that begin to paint a picture of how academics are using Twitter to navigate academia. Belinda reminds us of the possible interpretation of links between institutions and how an academic becomes strategic. Furthermore, Sally considers her practice strategically in regard to weighting the content she shares while also consciously connecting people with her professional tweet content.

When I got promoted recently and I realised that all my tweets were going to somehow be associated with where I worked as well, so I realised I needed to put a disclaimer on there. I didn’t want me representing the institution for what I was saying, so that got added in as well. (Belinda)

So my approach is I try to do it 80/20 – 80% professional, 20% personal – but depending on the day, sometimes it’s a little bit more personal but mostly it’s professional. The personal elements that I include are very strategic around helping people to connect with the professional stuff that I put out there. (Sally)

Self-awareness occurred and critical decisions were made in regard to how some academics strategically interacted with Twitter when feeling stressed. Rochelle discussed her use of Twitter as a focused activity, carefully mediated by how she felt and what she wanted out of it, while Mia reminds us that some academics using Twitter are not strategically thinking about followers, content or the audience.

When I get busy with work, or – this is an interesting thing – when there’s emotional things happening in my life, like difficulties and I feel a bit down, I really don’t like using Twitter. (Rochelle)

I’m probably an unusual user, I don’t really think of people who I connect with as my audience. I never look at whether they follow me or unfollow me or the status state or any of that stuff. I really am not interested in that. What I’m interested in is if I do believe in something strongly I reach the right people. (Mia)

Strategy, in terms of whom one engages with and how this links to professional online profile/identity across platforms was commonly discussed. For example, Brooke considers Twitter as one of many public profiles she maintains professionally where varying ways of interacting assist her in networking or hooking up.

So the critical decisions for me were about whether or not my Twitter profile fitted with the other parts of my professional digital identity which for me is my website, my LinkedIn profile, my blog and Twitter, so those four they’re public, they’re things that anybody can see about me and they need to have that balance between being informative and useful and actually performed identity and being professional and me staying that person to be more centric but not over sharing, that’s quite a hard line to balance. So I had to think about all of that. (Brooke)

Curating followers strategically was referred to by many participants in the study as a way to carefully manage their online identity. As Brooke mentioned, she carefully monitored her content, and Melissa indicated she deliberately regulated her audience.

Sometimes when somebody I follow interacts with me I don’t automatically follow back unless the person is clearly doing a PhD or is an academic because that looks like we’re going to be – I’m interested in closing that feedback loop, but mostly what I do is I meet people through recommendations. Those recommendations like #FollowFriday …[or] #ScholarSunday which is a really interesting initiative that I find much more helpful because I’m not looking for random names to follow, I’m looking for a particular kind of person who’s going to bring balance to my timeline. (Melissa)

Like-minded people, new connections, access to timely information, and future cross-institutional research collaborations were also highlighted throughout the interviews. This is one example:

Academic purposes is one of the integral personal aspects of me and so it’s certainly one of the ways in which I use Twitter...So I follow a number of people in higher ed[ucation] in Australia and internationally and it’s a really good source of information and intelligence and often I’ll hear things there first. So I find that kind of affordance really valuable. It’s put me in contact with a lot of people that I wouldn’t have otherwise met, professionally in academia and elsewhere. So I find it really useful for making interesting and valuable connections…In fact probably most of my new recent academic collaborations have been initiated via Twitter and probably with the people outside [insert institution]. So it’s been really useful in connecting me up with likeminded people who would like to collaborate that I know that I probably wouldn’t have found any other way. (Ross)

We conclude by suggesting that the role of social media in the university is a space for the influential building of academic networks that enable different ways for academics to become. The university is grounded in the relationships between people and contexts. When we think about relationships, how we woo, hook up and spin our stories, we consider some of the ways, habits, conditions and customs we use to fit and not fit into these academic contexts. We are attending to this space because of our own use of Twitter in our academic lives. To understand what it is to be an academic in the contemporary university is not a single story. There are multiple ways of being and becoming in academia that conflate and contradict more traditional lockstep progression.

For academics, Twitter enables a new way to engage with, think about, and participate in social practices of the academy. The process of creating a profile, engaging in microblogging and communicating within and across various communities supports academics to challenge visibility as a professional, influence networks, develop interconnectivity and build visible networks. These various and varied behaviours demonstrate a way of being and doing. Considering how one brands themselves and the subsequent stance of one’s self professionally becomes more fluid and visible when engaging with Twitter. The community allows for constant reflective practice in regard to content shared and how one’s identity is developed, grown and nurtured, as demonstrated through strategic and non-strategic practices shared throughout this paper. Highlighted is the way in which social media use is a powerful contestation to what it means to be an academic in the 21st century university. The use of social media in academia and for those working in this space supports a public representation of their academic selves and their research. The building of networks and connections with other scholars using Twitter to benefit their research interests and inquiries offers both social and cognitive engagement and a new way of doing and being.

Dr Narelle Lemon is a Senior Lecturer in Curriculum Studies at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. Her research agenda is focused on cultural engagement and participation in the areas of teacher capacity building and cultural organisations in galleries, museums and other alternative education settings, social media for professional development including Twitter and Instagram, and working in academia. Narelle blogs at http://chatwithrellypops.wordpress.com and tweets as @rellypops.

Email: n.lemon@latrobe.edu.au

Megan McPherson is a practising artist, educational researcher and has taught in the university art studio for 18 years. Megan is a PhD scholar in the Faculty of Education, Monash University, where she is conducting an interdisciplinary research study of the role of the critic in studio pedagogies. She is a Senior Lecturer at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. Megan tweets as @MeganMcPherson.

Email: megan.mcpherson@monash.edu; m.mcpherson@latrobe.edu.au

Dr Kylie Budge is the Research Manager at Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, Sydney, Australia. At the time of writing, she was Senior Lecturer at Victoria University. She completed her PhD at the University of Melbourne, where the focus of her research was creative practice and the teaching of art and design in higher education. Her research interests include researching art/design and creativity, social media and its intersections with art/design and learning contexts, and academic identity and development. Kylie tweets as @kyliebudge.

Email: kylie.budge@maas.museum