Introduction

Part-time teachers (PTTs) are a diverse and growing group in UK universities (Gilbert, 2013). PTTs comprise all those who work less than 1.0 full time equivalent. This paper reviews existing practice in relation to development opportunities for this diverse group and then uses empirical data to examine perceptions of professional development before briefly discussing implications of the findings. The development of PTTs is a topic that is of interest to PTTs themselves, educational developers and managers.

PTTs are a diverse group (Woodall et al., 2009), who may be semi-retired academics, those choosing to work part-time to achieve a better work/life balance, aspirational academics who would like to work full time but have a part-time contract, portfolio workers who combine jobs at more than one institution, research workers who teach as part of their contract, graduate students who teach as part of their scholarship conditions or casual staff on hourly-paid lecturer (HPL) contracts. This last group may consist of graduate staff who are not on a teaching scholarship, staff employed on fractional contracts elsewhere in the university and language tutors. PTTs may inhabit more than one role – for example, being an HPL in addition to being a non-academic member of staff, a student or a research worker. Individuals have different motivations for working part-time, and it is not easy to categorise them. Likewise, the work that PTTs do varies, from tutors to assessors, demonstrators, module convenors, and those designing and delivering programmes with a teaching load higher than some full-time staff.

The Higher Education Statistics Agency reported that in 2009/10 in the UK, 35% of staff were categorised as part-time, and in 2011/12, 82,045 staff were employed on ‘atypical’ contracts (University and College Union [UCU], 2013). However, numbers of PTTs are difficult to enumerate accurately (Bryson, 2004). This situation is not unique to the UK, with the casualisation of the academic workforce increasing in Australia (Ryan, Burgess, Connell, & Groen, 2013) and the US (Whitecross & Mills, 2003) among other countries. If patterns of employment in the UK are similar to those in Australia, where the estimated numbers of sessional staff increased by 17.4% in 2013 according to the latest government figures (Times Higher Education, 2014), this proportion will continue to increase (Gilbert, 2013). The situation in the UK can also be compared to that in the US, where the use of a long-term part-time faculty has been studied over the last four decades. The first survey of part-time labour was conducted in the 1970s (Rajagopal & Farr, 1992). One of the largest groups of PTTs is graduate teaching assistants (GTAs).

Graduate Teaching Assistants

The use of postgraduate students as graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) is an issue that continues to be monitored within the HE sector. There has been an expansion of GTAs utilised in various roles within the UK, the US and Australasia. Beaton, Bradley and Cope (2013, p. 83) believe this is in part because they “are cheaper to employ and easier to dispense with”. A survey on the use of teaching assistants within UK anthropology departments (Whitecross & Mills, 2003) found that 44% of those on teaching only contracts held permanent contracts, compared to 82% on teaching and research contracts. However, these figures did not include the majority of postgraduate teachers who were either not issued with contacts, or whose contracts were not included within institutional returns. Figures quoted by UCU (2013) do not suggest that the situation has much improved in the last decade. A survey of postgraduates who teach carried out in 2012 (NUS, 2013) reported on the numbers of students that were required to teach by their departments, the fact that teaching was often a requirement for funding, that recruitment procedures were not always fair and transparent and that induction, training, feedback and development were not always provided. Some authors have voiced concern that the quality of teaching in the UK will suffer if a substantial proportion of teaching is delivered by GTAs (or PTTs) who are not eligible to take part in the academic programmes because they are aimed at new academics on probation (Glaister & Glaister, 2013).

Not all postgraduate teachers are left without support. Partridge, Hunt and Goody (2013) reported on a teach through an internship scheme. PhD students were encouraged to apply for the scheme and were paid to attend 50 hours of professional development in addition to 104 hours of teaching and curriculum development duties. They found that the scheme enhanced not only postgraduates’ self confidence but also their career prospects and raised the status of teaching within a research intensive university. In Canada, the Higher Education Quality Council reported on two schemes in Toronto that focused on the use of teaching assistants for undergraduates and aimed to integrate them into the teaching team (Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, 2013). They recommended that formalised training programmes should be designed and made available for GTAs so that they could learn effective teaching practices and benefit from a culture that actively promoted good teaching and continuous development. In the UK, Bryson (2013, p. 11) found that some HEIs are developing initiatives that have “real potential” to support PTTs. Some GTAs are employed to teach on HPL contracts.

Hourly-Paid Lecturers

The University and College Union in the UK (UCU) report that the use of zero-hours contracts in the education sector has increased 10-fold since 2004 (UCU, 2013), and universities and colleges are twice as likely to employ staff on such contracts than other workplaces (Butler, 2013). UCU investigated the use of zero hours contracts in 2013 and contacted 162 HEIs across the UK. They reported that 47.2% of all teaching only staff were on zero hours contracts and 15.5% of all teaching staff constitutes those on zero hours contracts (UCU, 2013). Although perceptions may be that these large numbers of staff are “all doctoral students doing a bit of tutoring on the side” (Gill, 2013), it has been reported in the HE press that the UK is developing a ‘two-tier’ workforce, with a large proportion of academics feeling undervalued. Knight, Baume, Tait and Yorke (2007, p. 432) stated that there is still the assumption that teaching is done by full-time academic staff, and as numbers of PTTs rise, it is “vital that these teachers feel appreciated”. Their professional development as teachers has to be supported and taken seriously (Knight et al., 2007).

According to research and anecdotal evidence from HPLs and full-time academics, recruitment of HPLs is not always subject to the same robust and transparent guidelines as recruitment to other fixed-term or open-ended positions (Bryson, 2004; Bryson, 2013; Woodall et al., 2009). Casual teaching may be given out by the module convenor or assigned by the school with no interview process. Similarly, the role descriptors used to determine the salary of HPLs are not always associated with the equivalent role descriptors for full-time staff. Also, moving up the pay spine as an HPL is often not a transparent nor an automatic process, in part because contracts are often given out afresh each academic year. This inhibits the automatic progression up the pay spine that a full-time member of staff would receive. Although many Human Resources departments state that staff on HPL contracts have the same rights as those on fixed-term contracts, this policy does not mention the learning and development of staff as in the equivalent policy for open-ended contract employees.

Given the large numbers of individuals involved, if part-time staff are excluded from formal training, induction, CPD and appraisal processes, it has the potential to affect the quality of provision offered to students (UCU, 2013). Many individuals occupy part-time and sessional roles over a long period of time, which can make it hard to continue with research and reduce the likelihood that they will be considered for full-time positions (Whitecross & Mills, 2003).

Entry requirements for programmes for academic and professional development

Not all programmes for academic development are open to or aimed at PTTs. Due to the casual nature of many zero-hours or HPL contracts, and the often informal nature of allocating teaching to GTAs, PTTs may not always know the full extent of their teaching commitments in advance.

According to a survey of 192 HE Institutions conducted by Amanda Sykes in 2013, 28 had some element of academic or professional provision as compulsory for some staff, e.g. completion was a requirement of probation. Entry requirements for some courses were available online, and most were based on teaching commitments. When checked, they varied from evidence of 15 contact hours or teaching students on three separate occasions throughout a year, to the less specific – stating that the courses were for staff “currently teaching” or with “sufficient teaching”, to 150 teaching hours per year. Some courses stated explicitly that they were open to full and part-time staff who met the teaching requirements (for example, one HEI requires a 40-hour teaching load, although it assesses applications individually). Others stated that they were aimed at full-time staff as well as visiting tutors and teachers in fractional posts. For example, one course is open to postgraduates who teach, whereas at another institution the course is aimed at lecturers so that they could gain fellowship of the HEA and meet their probation requirements. A few HEIs have a separate course specifically aimed at GTAs and part-time teachers.

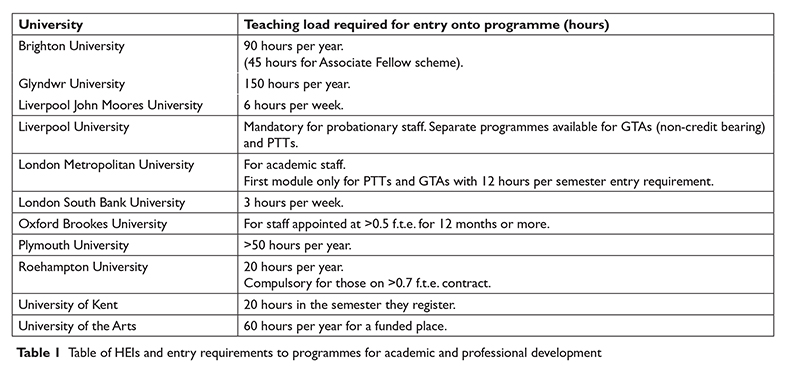

In order to gain more detailed information on entry requirements, especially whether programmes were open to PTTs, a query was posted to a Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA) JISC email list asking educational developers about the entry requirements to their courses and the accessibility of them to part-time teachers. Responses were received from 11 HEIs (Table 1). Five HEIs specifically mentioned provision for GTAs, either in that they had a separate programme, or access to all or part of the main programme. Most often this was a smaller, sometimes non-credit bearing option.

As can be seen from the variable entry requirements in Table 1, some courses that are available for academic and professional development are open to part-time teachers, but some are not. However, an Independent Review of Higher Education Funding and Student Finance in the UK specifically stated that “the option to gain a qualification is made available to all staff – including researchers and postgraduate students – with teaching responsibilities” (Browne, 2010, p. 45). From this small survey of provision of academic and professional development, there are obvious practical barriers in place that prevent this obligation to PTTs from being fulfilled. Providing options for all staff with teaching responsibilities has resource implications for the centres and departments that provide PGCerts and the like.

Survey of part-time teachers

In order to assess the accessibility of programmes for academic and professional development for part-time teachers in HE, I designed a survey to elicit views at one University in the Southeast of England, which was distributed in November 2012. This survey was not explicitly looking at PTTs’ views on the content of such programmes, but instead it was seeking to find out how accessible these programmes are, and how supported PTTs feel by their HEI.

Methodology

The limitations of using an online survey include the general limitations of survey methods (Silverman, 2006), such as restrictions on the type and number of questions, low response rates and difficulties in reaching the sample population. As such, the survey gave a general overview to the questions asked. However, where possible, room was given to the participants to expand on their answers, and the majority of participants chose to respond in this way, giving some rich qualitative data. Using an online survey designed through a popular survey website did ensure that costs were low as the free version was used, although this restricted the number of questions in the survey to 10. Anonymity was assured through the software, although participants were given an option to give their email address and/or to email the author directly if they had any further comments. If time and resources had allowed, it would have been ideal to complete a follow-up survey along with interviews with willing participants to interrogate their responses further. It must also be acknowledged that the sample population for this survey is relatively small and is from one HEI only. A larger survey including PTTs from a variety of institutions would be more representative of the views and experiences of PTTs across the Academy. Again, it must be noted that GTAs were not explicitly included within this survey, which is obviously a limiting factor when it comes to discussing the results with respect to the needs of all PTTs.

The Human Resources department (HR) at the University were approached to source contact details for the part-time teachers. HR provided a database of all individuals with an HPL contract. This included 816 entries – 43% of the total academic workforce according to the figures on the website. However, some individuals were listed on the database up to 4 times, as they had contracts with more than one school or department. All the email addresses provided were the university.ac.uk addresses given at point of employment; however, not all the addresses were current and working. Out of the 816 entries on the database, there were only 340 individual working email addresses (42%). It should be noted that the University was reported as having one of the top ten highest number of zero-hours contracts in the UK in 2013 (Morgan, 2013). Given the data from this survey, it may be assumed that this figure does not reflect the number of active individuals on contract to the University, but instead represents the numbers of contracts, with the actual number of zero-hours staff being much lower. A link to the HPL survey with an explanatory email was sent to the 340 working email addresses, and the response rate was 23% (n=78), or 10% of the nominal 816 in the HPL workforce. All the data were analysed using descriptive statistics, with comments analysed qualitatively.

Demographics

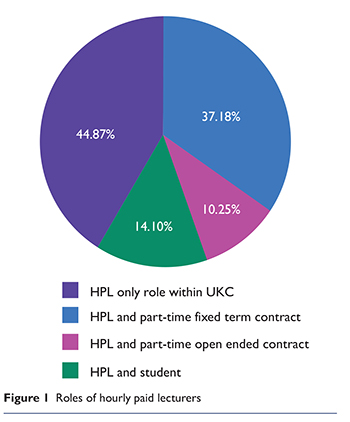

Of the HPLs who responded to the survey (n=78), 56% were female. Hours worked per year varied from 5 to 260. All respondents were asked about their role, whether they had more than one role with the University and whether they were students (Figure 1). Respondents were allowed more than one response.

Enthusiasm for development

Of the PTTs who responded, 91% stated that they wanted to develop professionally: “Of course, development is always a good thing.” (A.) “Any useful opportunities are welcome.” (U.) “It’s a no brainer – why wouldn’t I?” (P.)

Typical reasons for individuals not being interested in academic or professional development included: “I have many other commitments and teach elsewhere too.” (G.) “I am nearing retirement age so I am not sure how much effort I now want to put into my career.” (F.) “I already have considerable training, coaching and university teaching and a PGCert in HE.” (S.)

Areas for development

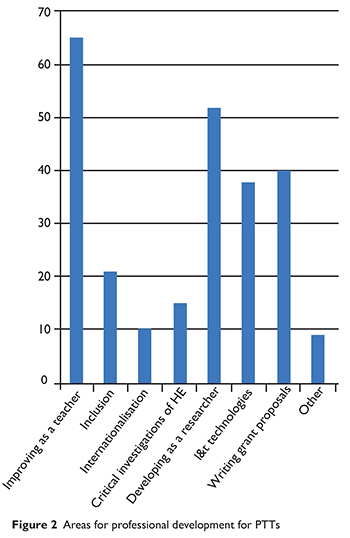

The respondents were asked to indicate areas of academic and professional development that they were interested in, out of a range of choices drawn from current professional development provision at the University (Figure 2). They were allowed to choose as many options as they wanted. The largest area was ‘improving as a teacher’, with 65 responses (78%). The second largest area was ‘developing as a researcher’ with 52 responses (67%). This indicates that HPLs are interested in improving their teaching and research. However, it should be noted that although a module Developing as a researcher is offered as part of the PGCert programme, it is not open to PhD students, who constitute 45% of the respondents. The GTAs at this institution have a Graduate School programme that is available to them and offers specific researcher development for PhD students, whereas the Researcher Development module on the PGCert is aimed at early career researchers who are already established.

‘Other’ areas asked for included professional teaching and learning, creative writing skills, learning more about his/her professional discipline, developing an artistic practice, commercialisation of academic ideas and innovation, internationalisation of small businesses and other training.

Access to development

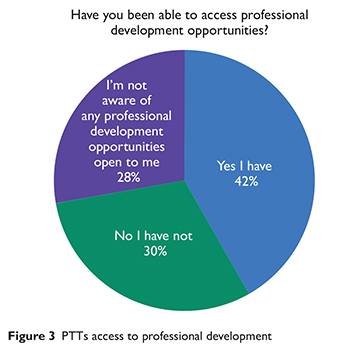

There were comments that indicated that some PTTs were unaware of options open to them:

I would like to develop professionally, but I don’t know what the options are. (V.)

I was unaware of any professional development courses/workshops that were open to me. (J.)

I am entirely unaware of development opportunities open to me nor invited to attend any on a central basis. I am under the impression that I cannot gain access to the same training as it may not be ‘in line’ with my current role or needs. (H.)

Respondents were asked if they had been able to access professional development opportunities open to them, including academic and professional development courses at an associate lecturer, postgraduate certificate, postgraduate diploma and Masters level (Figure 3). In addition, the University operates a network for early career researchers which is open to new academics and research workers (PhD students are welcome to attend if spaces are available), and a series of workshops aimed at grant bid writing, which are open to early career and all academics.

When the PTTs were asked what would make access to professional development easier, 53% indicated that a nominal attendance allowance would help. Historically, at this University, HPLs had been paid a nominal amount to attend training; however, this is no longer in place. Of those surveyed, 53% indicated that an intensive delivery mode would be helpful, whilst 21% asked for support from their Head of Department or line manager. Other issues that affected access to development included a lack of spaces on courses, a lack of funding, a lack of information about available courses, and the timing of courses: “No because 1. I was not at university while they were happening, or 2. I was at the University but just too busy at that moment as to attend.” (B.)

Appropriateness of development

Some respondents questioned the appropriateness of what they perceived the development on offer to be:

Is there any effort to provide HPLs with such information? I am aware such courses exist but have been focused on managing my workload and trying to complete research. As to PGCHE or similar, what tangible benefit would this bring to someone who is currently an AL [associate/assistant lecturer] and has been teaching for 4+ years? Career development appears dependent on publications, while attendance on such a course would simply make it less likely we would have time to publish. Developing teaching is of course important, but such courses can just as easily be undertaken when a lectureship has been obtained (and may in fact be required). As to Early Career networks, this could help some HPLs settle and has merit. But it has a danger of becoming a social support system, and is no substitute for some dedicated/functioning mentoring system for HPLs (who wish to avail of such a system) directed at developing and supporting their research. (K.)

This respondent raises important issues about the perceived importance of teaching vs research in career development.

Availability of development

Other concerns raised by respondents included the lack of space and places on the courses offered, along with the uncertainty of eligibility due to needing to know teaching hours as to meet the entry requirements:

Just started… after delays – initially due to not obtaining teaching work and subsequently because… oversubscribed. (L.)

There are not enough spaces on the course and as it is not a necessity for my studentship, I was not prioritised… the chances are I won’t be able to complete the PGCHE due to the oversubscription of the courses. (D.)

There also appears to be a lack of information about the courses and the costs involved. At this University, if the entry requirements are met, then there are no direct costs to the individual or the department, and yet two respondents mentioned that cost was a barrier:

I am not sure which ones are accessible to me as an hourly paid assistant lecturer, how to access them and what are the costs involved (for me and/or my departments). (C.)

I was initially refused … as it was deemed unnecessary for my role and that the department pay for that on my behalf. (I.)

Credit for development

Although there was some confusion about the question, 49% of the respondents stated that they preferred to undertake courses for credit, with only 24% preferring a not-for-credit option: “If something sounds really interesting and useful I’ll do it without credit…” (L.) “Would definitely be inclined to do courses if there was accreditation involved.” (R.)

Perceptions of development

The final question in the survey asked whether the respondents wanted to make any other comments on their academic or professional development. The most comments for any question were recorded here, although, as with all the other questions, comments were not required. Several respondents asked for more personalised development or support:

More personal development, the opportunity to discuss career progression with someone. (Q.)

In my School we do not have appraisals or any structured contact with a line manager. It is a big School and 45 AALs [associate/assistant lecturers] all report to the Head of School in theory, but there are no channels for professional development and the ways to progress through the Grades, or to a fractional or full-time post are not publicised or made explicit. Any move to bring this in across the University would be welcome and it would in my view be healthy for institution. (H.)

There were calls for more support to attend existing development courses: “It would be useful if there was more support from the Department and University for part time lecturers to encourage professional development.” (O.)

In part, this was due to the perceived benefit of networking with other PTTs and members of staff:

Professional development courses not only enhance us professionally but they also provide opportunities for networking and contact with other members of staff which is often lacking when one works on an hourly basis – one does not have access to a staff room, or coffee room or sometimes the capacity to attend staff meetings etc. I met some interesting people on the PGCHE and gained information and knowledge about the university from them. So the courses provide a huge amount of ‘value-added’ benefit. (O.)

Some respondents felt that the University was not that interested in HPLs, and left them to their own devices: “The chief means of support is from other HPLs within the department, with a conspicuous lack of support from the university as a whole.” (T.)

There was general disaffection with the use of HPL contracts for teaching: “There is too much reliance on HPLs, meaning there are fewer opportunities to gain full time positions at UKC. Universities are wasting young talent.” (G.)

There were concerns about the rate of pay for HPLs: “The rate is just face-to-face teaching and doesn’t take into account preparation, marking, office hours or exam-marking, so it’s fun, exciting, challenging and underpaid”. (F.)

There were pleas for funding opportunities:

One of the hardest aspects has been lack of support for individual research. I was refused funding to disseminate my work. I was told I could not apply for a small faculty grant in my own name. I have had no support from the HoD for developing a grant proposal – I was told that there was no point as I was on a fixed term contract. (S.)

The feelings of isolation, and disaffection, from full-time academic members of staff came across very clearly, along with a yearning for more and better support: “It is difficult to feel part of a team.” (A.) “I still feel quite isolated and disposable.” (B.)

Discussion

What is the role of programmes for academic and professional development in higher education?

The importance of development for academics becomes more of an issue with the growing marketisation of HE. As the job market for academics becomes harder, more emphasis is placed on the qualifications of those seeking employment, so that they can not only demonstrate subject knowledge with a PhD but also have a proven record of publications and grant applications and demonstrable teaching expertise. One way to do this is through an academic qualification. In a competitive job market, an HE teaching qualification may tip the scales in favour of a candidate, or conversely, it may become a prerequisite for employment. Likewise, as HEIs compete for undergraduate students whilst simultaneously attempting to reduce costs and increase efficiencies, using cheap, sessional staff may be a means to keep contact hours high whilst keeping costs to a minimum. However, if these staff are ‘unqualified’, this may reflect badly on the University and put off potential fee paying students who would prefer to be taught by fully qualified academics. If PTTs can undertake an academic or professional qualification to credentialise their teaching ability, then this could be reported positively. Of course, there is also the altruistic angle that professional and academic development of early career (and all) academics will benefit both the individuals and the students whom they teach.

The issue of whether such programmes should be for academic credit or not also has to be addressed. The survey results suggested that credit was a motivational factor for the majority of participants; however, these findings disagree with those of Knight et al. (2007, p. 424), who found that there was “less engagement in award-bearing courses than in non-award-bearing ones”.

Where do part-time teachers fit in to the Academy within the context of the ‘professionalisation’ of teaching in HE?

It is in part because of their diversity that PTTs are ‘invisible’. Strategies that aim to investigate one part of the target group, for example HPLs, may neglect to address the needs of GTAs or postgraduates who teach as some of them aren’t paid sessionally but as part of their bursary conditions. Likewise, research workers may get neglected if they teach as part of their research contract. Often, PTTs inhabit more than one role within a University, and so any strategy that aims to address professional and academic opportunities for PTTs needs to be comprehensive and holistic.

If an HPL has limited time available, they have to balance the perceived benefit of programmes for development to their career with the time available; as one survey respondent stated, “I’m aware they exist, but my other work precludes taking them up.” However, there is evidence from New Zealand to show that academics who have completed a teaching qualification have a higher research output than those who have not, and that “academics who approach their academic roles holistically – understanding themselves to be researchers, teachers and academic citizens – are more likely to thrive in the research area of their work” (Sutherland, Wilson, & Williams, 2010, p. 55).

>One respondent from the survey raised the legitimate question of whether HPLs are aware of the courses and opportunities on offer to them. The results indicated that 30% of the HPLs who responded were unaware of any professional development options, and that out of the 814 HPLs the University had on contract there were working email addresses for only 340 of them. This indicates that central information about professional development (or any communication) may not be getting through to PTTs, contributing to their feelings of isolation.

An holistic approach to academic development, and not one that focuses solely on teaching and learning, may be more beneficial to PTTs, and all academics. This approach better reflects the entirety of academic work (Malcolm & Zukas, 2009) and is more likely to support staff to become research active (Sutherland, Wilson, & Williams, 2010). Not all participants would wish to complete an entire programme of professional development, and not all will embrace such a programme positively (Trowler & Cooper, 2002). However, those staff who perceive the provision of support and training to be effective are more likely to be satisfied overall (Sutherland, Wilson, & Williams, 2010).

What are the views of part-time teachers on professional development opportunities available to them?

The large numbers of respondents who were keen to develop professionally, particularly in the areas of research and teaching, may well reflect the findings that three quarters of research staff aspire to a career in HE (Gibney, 2013). These findings, from the Careers in Research Online survey of 8,216 research staff, reinforced the importance of providing appropriate career guidance to early career staff.

From the survey results, the majority of staff at this University were unhappy with the level of support that they perceived was available to them. However, there was considerable confusion about development opportunities and options. In addition, there was general evidence of feelings of discontent with aspects of PTT, including the pay, the lack of individual and personalised support from within the school or department, a lack of information about career progression and a lack of integration into the department. Further research comparing different types of HEIs would be beneficial to establish whether these perceptions are found across the sector.

Conclusions

With regard to PTTs, it can be seen that access to development and support is limited for many (Bryson, 2013). As the use of PTTs as a resource continues to increase, it may become important that their professional development needs are taken seriously (Knight et al., 2007), and that institutional policy and practices are in place to support their teaching as well as their general academic development (Woodall et al., 2009). These would include clear conditions of work, recruitment and induction procedures, access to development courses (for example, using intensive models of delivery, and ensuring that entry requirements do not exclude PTTs), and setting up dedicated mentoring and support networks. Many of the PTTs who took part in this survey were unhappy with the support and development provision that they had available to them. Such disaffection from PTTs seems to be common. In Australia, Ryan et al. (2013) reported on the exclusion and marginalisation reported by casual or sessional academics as compared to full-time academics.

It seems that the drivers for academic and professional development continue to exhibit tensions between the desire to show competency and accredit teachers and the intention to develop early career academics to achieve their full potential as teachers and researchers. Coupled with the pressure on academic jobs resulting in high competition for post-doctoral positions and full-time academic posts with increasing numbers of sessional staff, including PTTs and GTAs being used to supplement undergraduate teaching, this may affect the professional and academic provision for staff in the future.

Biography

Jennifer Leigh joined the Centre for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Kent full-time in 2013. She previously worked as a Research Associate for the Tizard Centre at the University of Kent. Her research interests include academic practice, programmes for academic development and part-time teachers as well as aspects of teaching and learning in higher education.

Email: j.s.leigh@kent.ac.uk